Western Indian Ocean Islands and coastal and marine environments

Contents

Introduction

Pollution and the impacts of climate change (Western Indian Ocean Islands and coastal and marine environments) , including coastal erosion and coral bleaching, are the main concerns for this region. The potential impact of anticipated sea-level rise is also a major issue. Southern areas, including Mauritius, Réunion and Madagascar, are subject to frequent tropical cyclones, causing loss of life and widespread devastation and destruction of coastal infrastructure.

Overview of resources

The islands form a heterogeneous group, reflecting their contrasting geological origins – micro-continental (Madagascar and the granitic islands of the Seychelles Bank), volcanic (Mauritius and the Comoros) or lowlying coralline (e.g., Aldabra in western Seychelles). The Seychelles Bank and Mauritius form the ends of the crescentic Mascarene Plateau where the ocean shoals to less than 200 meters (m). All countries except Madagascar are classified as Small Island Developing States (SIDS), acknowledged to be especially dependent on their coastal and marine resources. All have large exclusive economic zones (EEZs) in relation to their land areas. The combined EEZs cover an ocean area of approximately 3.8 million km2, while the total land-cover is only 586,250 km2, of which Madagascar constitutes about 99 percent.

The seas are endowed with rich and varied coastal and marine ecosystems, including parts of the Somali Current and Agulhas Current large marine ecosystems (LMEs). There are extensive coral reefs, covering some 5,000 km2, with 320 species of hard corals (Figure 1) and, notably on Madagascar, coastal wetlands. The reefs constitute an important resource for fishing, tourism and recreation, as well as providing protection to vulnerable shores against potentially damaging waves. There are many endemic species, as well as endangered species including turtles, dugongs and cetaceans.

Fringing reefs almost completely surround the islands of Mauritius (including Rodrigues) and the Comoros islands, while many fringing and patch reefs occur around the granitic islands of the Seychelles. The island of Aldabra, a designated World Heritage Site in the western Seychelles, is a classic atoll (a massive growth of coral). In Madagascar there are extensive coral reefs in the south-western and northern parts of the island, all affected by the bleaching event of 1998 as a result of unusually high sea-surface temperatures. Live coral cover was reduced to less than 10 percent around some of the Seychelles’ granitic islands, while Mauritius was relatively lightly affected.

The deep waters surrounding the Comoros are home to the coelacanth, a living representative of a family of fish known to have existed 370 million years ago. Coelacanths have also been reported in the adjoining waters of Southern Africa and are the subject of a regional project, the African Coelacanth Ecosystem Programme. Coastal wetlands are extensive in Madagascar where mangroves cover an estimated 340,000 hectares (ha). More than 30 km2 of mangrove stands are present in the Comoros. In the Seychelles, remaining mangrove totals only 29 km2, the largest areas being on the western islands, including Aldabra. In the sub-region as a whole, there are 15, mostly coastal, marine protected areas (MPAs), established for different purposes and with different styles of management.

All the countries have important marine fisheries resources. In addition to the inshore and reef fisheries traditionally exploited by artisanal fishers, the fisheries resources include the offshore demersal fishery of the banks of the Mascarene Plateau and the Chagos Archipelago, as well as extensive oceanic tuna fisheries that support commercial industries in Mauritius and the Seychelles.

Offshore geophysical and geological exploration for oil has taken place on the Seychelles Bank since the 1970s, with minor exploration drilling. The geochemical analyses and exploration data from its offshore acreage indicate potential for commercial production. In 2005, an agreement was signed for exploration rights around Constant, Topaz, Farquhar and Coetivy islands. There are no known oil and gas reserves in Mauritius. In Madagascar, the existence of oil and gas reserves has been confirmed; Bemolanga and Tsimiroro are exhumed oil fields, while numerous other wells include oil shows. It has a modest production of crude and gas, with reserves of 70 x 109 cubic feet of natural gas. A field off the west coast containing heavy oil was proved in 2003, but deemed to lie too deep and to be too heavy to be commercially viable. Offshore exploration has continued over the last decade in the Majunga basin, off the west coast.

Endowments and opportunities

The island states are valued for their outstanding natural beauty and tropical biodiversity, but are under pressure from land-based pollution and degradation of coastal wetlands and beaches. Tourism is already a major foreign exchange earner and is becoming increasingly important, particularly in the Seychelles and Mauritius. Directly and indirectly, tourism accounts for much of the employment in the SIDS, for women as well as men. The Seychelles already has a buoyant tourist industry, currently with a maximum of about 130,000 tourists per year. It is planned to increase arrivals to 200,000 by 2010. The Seychelles’ tourism economy (direct and indirect impact) in 2005 was expected to account for 60.2 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) and 76.7 percent of total employment and was expected to grow by 14.0 percent in 2005. Mauritius’ tourism in 2005 was expected to account for 31.6 percent of GDP and 33.9 percent of total employment. It was expected to grow by 12.7 percent in 2005. Tourism in Madagascar and the Comoros is less developed, but both countries have a great development potential, with tourism the primary foreign exchange earner in Madagascar.

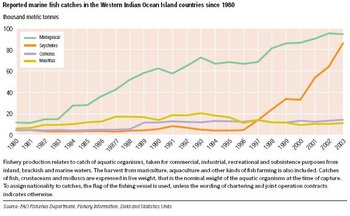

Fisheries contribute significantly to all the national economies. Stocks within exclusive economic zones (EEZs) are exploited under license by foreign fleets and license fees form a significant proportion of national revenue. The fisheries are known to be nearly fully exploited and overfishing may have already occurred in many [[coastal] areas], with most of the largely artisanal coastal fisheries being exploited beyond their maximum sustainable yield (MSY). Overall catches have increased over the past three decades to a level that has been more or less stable in recent years, but with a decline in Mauritius and the Comoros (Figure 4). There is scope for improvement in the quality of fisheries catch data for the purposes of policy making and management. Some marine fisheries may have scope for development, subject to enforcement of regulation at national and international levels. In the Seychelles, where there is now a highly developed tuna industry, including a canning factory employing 1,800 workers, fishing has become the largest earner after tourism, contributing 12-15 percent to gross domestic product (GDP). License fees of US$8 million are collected every year, with income from indirect expenditure (port dues, food supplies, services, etc.) amounting to over US$2 million. The Seychelles particularly, but also Mauritius, have important canning and transhipment facilities for tuna.

Aquaculture is a developing industry in all countries except the Comoros. The islands’ coastlines are well suited for several types of aquaculture development. Such developments present scope for increasing food security, in particular for coastal populations, and provide new sources of income for local economies and export markets. In Madagascar, there has been extensive conversion of coastal wetlands and mangrove areas to pond culture. In Mauritius, commercial aquaculture, mostly in freshwater ponds, consists of the production of giant freshwater prawns and red tilapia.

Challenges faced in realizing development opportunities

All countries are signatories to the UNEP-administered Nairobi Convention, which has a cooperative and coordinated approach to protection and enhancement of the marine and coastal environment. Similar resource development objectives are iterated specifically for Small Island Developing States (SIDS) in the Mauritius Strategy for the Implementation of the Programme of Action for the Sustainable Development of Small Island Developing States.

Major efforts are needed to regulate the pressures that are now leading to extensive habitat loss and degradation. The tasks involve sea-use and catchment management as well as the management of coastal resources. The island states have made considerable strides in establishing effective resource management. In Mauritius, new marine protected areas (MPAs) have been proclaimed, with supporting regulations and long-term monitoring of coral and fish communities, and in the Comoros, management of the environment and [[coastal] zone] has become a priority. Madagascar has adopted regulations to protect the natural environment, including marine areas, while the Seychelles has a national environmental management plan as well as a national biodiversity action plan that guides marine and terrestrial biodiversity conservation.

Concerns over the impacts (Impacts of tourism and recreation in Africa) of tourism development on the environment in some countries, including Mauritius and the Seychelles, are to be addressed through the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) in a major Global Environment Fund (GEF)-funded project entitled Reduction of Environmental Impact from Coastal Tourism through Introduction of Policy Changes and Strengthening Public-Private Partnerships. This initiative recognizes the importance of protecting the attractiveness of the coastal resources in order to sustain the tourism market in the long term. The development of tourism is creating new coastal nodes, as at Grande Baie in Mauritius. However, this type of development is often poorly controlled and is leading to the deterioration of coral reefs and the loss of the natural tourism attraction. Much of the original coastline has been physically altered, and habitats destroyed by dredging and filling operations and the sediment plumes which they generate. Pollution due to the improper disposal of solid waste and eutrophication, due to poor sewage treatment, were identified as severe concerns in the Indian Ocean Islands Global International Waters Assessment (GIWA). In Mauritius, preliminary surveys indicate damaging nutrient levels in many areas, which may have caused the development of six red tides in 1996 in the Trou-aux-Biches area. The coastal impacts of the widespread use of nitrate fertilizers and pesticides in the island’s agriculture raise particular concerns. Two major GEF-funded projects relate to pollution in the coastal and marine environment. Land-based activities impacting on coastal and marine resources are being addressed through UNEP under the Western Indian Ocean Land-based Activities Project (WIO-LaB), and the problems of oil spills are being covered by the Western Indian Ocean Islands Oil Spill Contingency Planning project.

Coral reefs continue to suffer pressures from increasing populations, coastal development, and marine-transported litter. Mining of coral and sand for use in construction is also damaging habitats, with most states implementing stricter legislation and licensing. Intensive tourism is thought to be damaging to reef habitats by pollution from boats, hotels and other facilities, and by anchor damage, trampling and removal of coral as souvenirs. Degradation of coral reefs is especially detrimental to the dive tourism industry. Fishing with dynamite, a common practice in the Comoros despite awareness campaigns, threatens coastal ecosystems. Stresses on reefs have been exacerbated by coral bleaching events. Since the 1998 event, which reduced live hard coral cover on many reefs to less than 5 percent, there have been further, though smaller, damaging episodes. Some reefs are showing recovery. Further pressures come from agriculture, where nutrients and sediments are discharged at the coast, particularly during cyclones. In Madagascar, deforestation is exacerbating soil erosion and sediment run-off.

Overexploitation of the inshore and reef artisanal fisheries, including the non-selective and destructive practices of dynamite fishing, purse-seining and dragnetting, is a serious issue. The offshore fisheries have provided strong growth in production over the last two decades. However, there is an urgent need to develop institutional capacity in the region to address the problems facing fisheries, with an emphasis on regional institutions to deal with transboundary and highly migratory stocks, and to cope with high seas issues. The major challenges to productivity and biodiversity in the region’s fisheries stem from a lack of regional cooperation and political will, poor monitoring and scientific capacity, and inadequate compliance structures. Biodiversity issues include concern over the large catches of non-target, endangered species, especially turtles, dolphins and dugongs. In the Seychelles, by-catch in the industrial tuna fishery constitutes 25-30 percent of the catch. The unregulated development of coastal aquaculture could pose serious environmental threats and cause conflict amongst coastal communities. The practice of mangrove clearance for the construction of prawn ponds is a particular issue in Madagascar.

Improving management demands investing in and building local capacity in all sectors of the fishing industry, to reduce the reliance on distant water fleets and to adopt regional approaches to fisheries management. A long-term project due to begin in 2006 – the GEF-World Bank-supported South West Indian Ocean Fisheries Project (SWIOFP), designed to interface with a GEF-UNDP initiative to study the Agulhas Current and Somali Current LMEs – should bring an unprecedented level of scientific and management cooperation. In another project, a framework for regional fisheries management of non-tuna species is being developed, through the establishment of the South West Indian Ocean Fisheries Commission (SWIOFC). A non-binding coastal arrangement is in place within this framework, and negotiations are under way for a binding high seas arrangement.

Coastal erosion due to the impact of large waves is a major issue and has serious implications for tourism development. The extent to which upward reef growth and platform sedimentation might keep pace with sea-level rise is unknown, but it is likely that the protection from large waves offered by reefs will become less effective. In the extreme case of the Indian Ocean tsunami impact of 26 December 2004, damage in the Seychelles was estimated at US$30 million. Even where shores are fringed by extensive reef platforms and lagoons, as around Mauritius, they may be susceptible to erosion. The most critical coasts are those formed by low-lying beach plains, where former beach sands have accreted on rock platforms (the so-called “plateau” sands of the Seychelles islands such as Praslin and La Digue). Attempts have been made to stabilize shorelines in the Seychelles by the installation of groynes, and in Mauritius by the use of rock-filled wire gabions. The erosion of beaches and non-rocky beachhead materials is likely to be aggravated by rising eustatic sea level and an increasing frequency of storm surge events arising from global climate change. In the Seychelles, a national beach monitoring program was launched in 2003.

Further Reading

- African Coelacanth Ecosystem Programme (ACEP) Homepage.

- Ahamada, S., et al., 2004. Status of the coral reefs of the South West Indian Ocean Island States. In Status of Coral Reefs of the World: 2004 (ed.Wilkinson, C.), Vol. 1.

- EIA, 2005. Country Analysis Briefs. Energy Information Administration.

- FAO Fisheries Department Homepage

- Francis, J. and Torell, E., 2004. Human dimensions of coastal management in the Western Indian Ocean region. Ocean and Coastal Management, 47(7-8),299-307.

- IPCC, 2001. Watson, R.T. and the Core Writing Team (eds). Climate Change 2001: Synthesis Report. A Contribution of Working Groups I, II, and III to the Third Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. ISBN: 0521807700

- Kairu, K. and Nyandwi, N. (eds. 2000). Guidelines for the Study of Shoreline Change in the Western Indian Ocean Region. IOC Manuals and Guides No. 40. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, Paris.

- Linden, O. and Sporrong, N., eds. 1999. Coral Reef Degradation in the Indian Ocean – status report and project presentations 1999. Coral Reef Degradation in the Indian Ocean, Stockholm, Sweden.

- Rönnbäck, P., Bryceson, I. and Kautsky, N., 2002. Coastal aquaculture development in Eastern Africa and the Western Indian Ocean:Prospects and problems for food security and local economies. Ambio, 31(7-8):537-42.

- Taylor, M., Ravilious, C. and Green, E.P., 2003. Mangroves of East Africa. UNEP-WCMC Biodiversity Series No. 13.

- UNEP, 2002. Africa Environment Outlook: Past, Present and Future Perspectives. United Nations Environment Programme, Nairobi. ISBN: 9280721011

- UNEP, 2004. Indian Ocean Islands. Global International Waters Assessment, Regional Assessment 45b. University of Kalmar, Kalmar, Sweden.

- UNEP, 2005a. After the Tsunami: Rapid Environmental Assessment. United Nations Environment Programme, Nairobi.

- UNEP, 2005b. Atlantic and Indian Oceans Environment Outlook. United Nations Environment Programme, Nairobi. ISBN: 9280725254

- UNEP, 2006. Africa Environment Outlook 2

- UNEP/GPA, 2004. Shoreline Change in the Western Indian Ocean Region: An Overview. Report prepared by Western Indian Ocean Marine Science Association (WIOMSA) for United Nations Environment Programme / Global Programme of Action, The Hague.

- UNEP-WCMC, 2000. Marine Information. United Nations Environment Programme’s World Conservation Monitoring Centre.

- UNESCO, 2005. World Heritage Centre – World Heritage List. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization.

- WIO-LaB, 2005. Addressing Land-based Activities in the Western Indian Ocean.

- UNEP/GPA and WIOMSA, 2004. Regional Overview of Physical Alteration and Destruction of Habitats (PADH) in the Western Indian Ocean region.A report prepared by the Western Indian Ocean Marine Science Association for United Nations Environment Programme / Global Programme of Action,The Hague.

- UNEP-WCMC, 2000. Marine and Coastal Programme Database. United Nations Environment Programme’s World Conservation Monitoring Centre.

- WTTC, 2005. Country League Tables – Travel and Tourism: Sowing the Seeds of Growth – The 2005 Travel & Tourism Economic Research. World Travel and Tourism Council, London.

|

|

| Disclaimer: This article is taken wholly from, or contains information that was originally published by, the United Nations Environment Programme. Topic editors and authors for the Encyclopedia of Earth may have edited its content or added new information. The use of information from the United Nations Environment Programme should not be construed as support for or endorsement by that organization for any new information added by EoE personnel, or for any editing of the original content. |