Western Africa and coastal and marine environments

Contents

Introduction

The main concerns of the mainland states are the degradation of their coastal habitats and biodiversity (Western Africa and coastal and marine environments) through pollution, saline intrusion and erosion, and the overexploitation of their fisheries resources. The coastal degradation has contributing causes in the pressures generated by an expanding coastal population, urbanization and industrial development. This includes the development of coastal and offshore oil and gas resources. In some countries, these pressures have been exacerbated in recent years by human conflict and political instability. The damming of rivers, reducing the amount of freshwater and sandy sediment being discharged at the coast, contributes to the degradation of coastal wetlands and coastal erosion. The potential impacts of climate change and sea-level rise, particularly with regard to coastal erosion and the inundation of coastal lowlands, are important issues in coastal land use and planning.

Overview of resources

Mangrove forests (dark green) fringe estuaries and tidal creeks in Guinea-Bissau. (Source: NASA Earth Observatory) Western Africa’s varied coastal zone extends for some 4,400 km, from the desert sandy shores of Mauritania in the north, through deeply indented, estuarine and island coasts (eg Guinea-Bissau with its Bijagos archipelago), to the lagoonal coasts with their extensive barrier beaches on the Gulf of Guinea. The huge delta of the Niger and Cross rivers forms its eastern end. Major rivers – Senegal, Volta, Niger –drain the hinterland, each dammed variously for agricultural irrigation and hydropower, altering the nature of water and sediment discharge to the coast. The volcanic, mountainous SIDS of the Cape Verde Islands lie some 600 km west of Dakar, Senegal. The seas off Mauritania, Senegal and Gambia form part of the Canary Current large marine ecosystems (LME), sustained by the cold, southward flowing Canary Current, with its nutrient-rich coastal upwellings. Countries from Guinea-Bissau to Nigeria flank the Guinea Current LME which is sustained by the eastward-flowing Guinea Current. Seasonal upwelling of cold, nutrient-rich water occurs off the coasts of Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire. Both LMEs have substantial fisheries resources. Both are driven by climate, with intensive fishing as their secondary force. Commercially valuable fish in the Canary Current LME include cephalopods, tuna and hake. In both LMEs, more than half of the commercial catch comprises small pelagic clupeoids (herring, sardines and anchovies). Many coastal wetlands support important fisheries. Box 1: The Cape Verde Islands and the West African Marine Eco-region (Source: WWF 2005) Mangroves are abundant in the Niger delta, covering many thousand square kilometres, and also in Guinea-Bissau (2,366 km2) and Senegal (1,690 km2). Coral reefs occur only in the Cape Verde Islands (Box 1). The coastal waters are home to endangered species including marine turtles, inshore cetaceans and the West African manatee. There are many designated coastal wetland protected areas, with some twenty Ramsar sites, notably in Mauritania, Senegal, Gambia, Guinea, Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana and Benin. Banc d’Arguin, in Mauritania, is a UNESCO World Heritage site where the desert environment is juxtaposed with biodiverse coastal habitats over more than 180 km of shoreline. Many of the coastal wetlands support important fisheries. Cultural World Heritage sites include the island of Gorée off the Senegal coast at Dakar. From the 15th to the 19th century, this was the largest slave-trading centre on the African coast. Western Africa has important hydrocarbon resources. Oil and gas have long been developed in the Niger delta, but now there is increasing exploration and development in most countries, mainly in offshore sites in water depths ranging from shallow to ultra-deep, beyond the continental shelf. Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) statistics list Nigeria’s estimated crude reserves at 31,000.5 million barrels. Smaller oil (and significant gas) reserves are located offshore in the Gulf of Guinea in Benin, Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire, also offshore Senegal and Mauritania, where the Chinguetti field, located in deep water near the capital, Nouakchott, was proved in 2001 to be commercial. There are also significant reserves of natural gas, which amount to approximately 32 percent of Africa’s natural gas reserves. Nigeria’s gas reserves are the ninth-largest in the world. The West African Pipeline project, carrying gas from Nigeria to Benin, Togo and Ghana is set to proceed. While Nigeria is likely to remain by far the largest producer of oil and gas, nearly every country has attracted exploration interest. (Western Africa and coastal and marine environments)

Endowments and opportunities

The coastal areas of Western African countries have dense and growing populations and developing commerce. This is where most of the industrial infrastructure is located, historically because of access to port facilities. In Nigeria, about 10 percent of the total population of over 120 million live in the coastal city of Lagos, which is also the centre for 85 percent of the country’s formal industry. Coastal cities are likely to continue to be nodes of population growth for the foreseeable future, with opportunities over the longer term for people to improve their economic well-being. As well as the intrinsic attractions of coastal areas for growing populations, rich biodiversity and marine fisheries, and the extensive coastal and offshore oil and gas fields, are key assets with potential for boosting economic development and alleviating poverty.

Oil and gas development offers most countries a prospect of economic growth as well as a contribution to their energy needs. Nigeria is the only significant oil producer, with production exceeding 2 million barrels per day (bbl/d) in 2003. It ranks as the sixth-largest oil producer in the world, with exports accounting for 95 percent of the country’s foreign income. Nigeria has the potential to maintain its already substantial crude oil production as recent discoveries in new deep-water projects come on stream. The offshore Joint Development Zone, shared by Nigeria with neighbouring São Tomé (Central Africa), could soon potentially yield up to 3 million bbl/d. Nigeria is developing several projects to utilize its vast reserves of natural gas. Much of the present gas production from oilfields is flared. The projects involve the reinjection of gas into oilfields to maintain pumping pressure, and processing to produce liquefied natural gas (LNG). There are also schemes being planned to distribute gas for domestic and transboundary consumption.

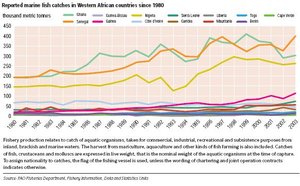

Marine fisheries make an important contribution to food security, employment and national income, with Ghana, Senegal and Nigeria the main producers. In the Cape Verde Islands, fishery products represent 63 percent of the state’s exports. Significant changes in species composition and fishery patterns have occurred, apparently partly due to overfishing, as shown by a decline in CPUE and the taking of immature fish by artisanal fishers.

Tourism has potential for substantial growth, with the biodiversity and socio-cultural heritage aspects of many coastal areas providing a strong attraction. Ecotourism in particular should thrive with improved management of national parks. Individual countries show wide variations in their overall travel and tourism statistics and forecasts. Given trends elsewhere, it is plausible that coastal areas make a significant contribution to tourism. Ghana’s travel and tourism economy in 2005 was expected to account for 10.8 percent of GDP and 11.5 percent of total employment.

Challenges faced in realizing development opportunities

Box 2: Diawling National Park, Mauritania-an area of important biodiversity

Box 2: Diawling National Park, Mauritania-an area of important biodiversity(Source: IUCN)

All countries are signatories to the UNEP-administered Abidjan Convention. The environmental issues and challenges faced in the realization of development opportunities are being addressed at local to global levels within this framework. Important initiatives in the control and reduction of pollution are already in progress, with the member countries committed to reducing and controlling land-based sources of pollution.

The continuing growth of coastal populations, and in particular the increasing urbanization along the coast, is placing severe stress on the living resources through physical disruption and pollution, resulting in the degradation or loss of habitats that have crucial value in ecosystem services and biodiversity. One such example is the Diawling National Park (Box 2) on the estuary of the Senegal River, where damming has led to restricted freshwater flow in the dry season. Aquatic weeds, such as the Nypa palm, infest many estuaries.

The intensity of industrial-scale marine fishing, notably by foreign fleets operating under licensed agreements, also continues to increase, with serious impacts on fish stocks. Despite increasing catches by foreign fishing fleets, the economic growth and social benefits from marine resources have not been realized in many Western African countries that host these fleets. Alongside the impacts on living resources, there has been a rapid expansion in seabed and marine engineering for the development of oil and gas resources, with accompanying air pollution and the ever-present risk of extensive oil pollution. The scale of environmental destruction and accompanying civil unrest arising from oil production operations in the Niger delta over the last few decades serves as a shocking indictment of the industry.

Coastal erosion by wave action has long been an important issue on the high-energy coasts of Western Africa. Reductions in the discharge of sand, due to damming and the disruption of longshore sand transport by coastal engineering such as port development, have exacerbated this process. Some shorelines, such as the sand spit of Langue de Barbarie at the mouth of the Senegal River, have shown periodic erosion and accretion, mostly without obvious human influence.

The issue of climate change and its anticipated, associated sea-level rise has important implications. As well as the increasing desertification of the Sahel (which may lead to further increases in coastal populations), there is likely to be an increase in coastal erosion and inundation of what are now densely populated low-lying areas, such as the Victoria Island beaches in Lagos, Nigeria, and the Greater Banjul Area in Gambia.

Further reading

- Alder, J. and Sumaila, U.R., 2004. Western Africa: A fish basket of Europe past and present. Journal of Environment and Development. 13(2), 156-78.

- Crossland, C.J., Kremer, H.H., Lindeboom, H.J., Marshall Crossland, J.I. and Le Tissier,M.D.A., eds. 2005. Coastal Fluxes in the Anthropocene –The Land-Ocean Interactions in the Coastal Zone Project of the International Geosphere-Biosphere Programme. Global Change – the International Geosphere-Biosphere Program Series. Springer, Berlin.

- EIA, 2005. Country Analysis Briefs. Energy Information Administration.

- FAO, 2005. FAOSTAT Database. Fisheries Data. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

- Hamerlynck, O. (1999). Use and abuse of deltas.World Conservation. 2/99, 11-12.

- IPCC, 2001. Watson, R.T. and the Core Writing Team (eds). Climate Change 2001: Synthesis Report.A Contribution of Working Groups I, II, and III to the Third Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- IUCN, 2003a. Regional Strategy for Marine Protected Areas in West Africa. IUCN – The World Conservation Union.

- Jallow, B.P., Barrow, M.K.A. and Leatherman, S.P., 1996. Vulnerability of the coastal zone of the Gambia to sea-level rise and development of response strategies and adaptation options. Climate Research. 6 (2), 165-77.

- NOAA, 2003a. Guinea Current Large Marine Ecosystem, LME No.28. United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

- UNEP, 1999. Global Environment Outlook-2000. United Nations Environment Programme, Nairobi.

- UNEP, 2006. Africa Environment Outlook 2

- UNEP-WCMC, 2000. Marine Information. United Nations Environment Programme’s World Conservation Monitoring Centre.

- UNESCO, 2005. World Heritage Centre – World Heritage List. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization.

- URI, 2003. Large Marine Ecosystems of the World – LME #27: Canary Current. University of Rhode Island.

- Wetlands International, 2005. Ramsar Sites Information Service.

- WTTC, 2005. Country League Tables – Travel and Tourism: Sowing the Seeds of Growth – The 2005 Travel & Tourism Economic Research. World Travel and Tourism Council, London.

|

|

| Disclaimer: This article is taken wholly from, or contains information that was originally published by, the United Nations Environment Programme. Topic editors and authors for the Encyclopedia of Earth may have edited its content or added new information. The use of information from the United Nations Environment Programme should not be construed as support for or endorsement by that organization for any new information added by EoE personnel, or for any editing of the original content. |