Southern Africa and coastal and marine environments

Contents

Introduction

The main challenges facing the sustainable use of coastal and marine resources are the loss of natural habitat and biodiversity (Southern Africa and coastal and marine environments) , and the consequent loss of any opportunity of exploitation of renewable living resources. Other concerns include the long-term effects of climatic change and sea-level rise, and the interruption of coastal processes such as sediment supply, beach dynamics, and degradation of water quality due to human activities in catchment and estuaries. There are difficulties in managing human activities impacting on the environment because of inadequate legislation and compliance, the lack of capacity for detection, and inadequate education and environmental awareness. All these factors are exacerbated by poverty and disease, and, in some countries, conflict and migration.

Overview of resources

Figure 1: Global distribution of mangrove, sea-grass and coral diversity (Source: Groombridge and Jenkins 2002; Maps prepared by UNEP WCMC) The coastal and marine areas, which extend along the 10,000 kilometers (km) of coastline from Angola on the Atlantic Ocean side to Tanzania on the Indian Ocean side and offshore to the limit of the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), encompass diverse living and non-living resources. The west coast is characterized largely by desert conditions and sparse human populations, but with rain forest established towards the mouth of the Congo River. Its seas are influenced by the cold, northward flowing Benguela Current, with highly productive upwellings supporting industrial-scale fisheries. The east coast, under the influence of the East African Coast Current which flows northward along the coast of Tanzania and the warm, southward flowing Mozambique and Agulhas currents, is sub-tropical in South Africa, becoming tropical and wetter northwards. Marine diversity increases towards the warmer zones. Much of the hinterland drains to this coast through rivers including the Rufiji, Zambezi, Limpopo and Incomati. In Mozambique and Tanzania, there are extensive coral reefs and sea-grass beds, and mangrove forests, especially around the Rufiji and Zambezi deltas (Figure 1), which are largely protected by barrier beaches. Parts of the South African coast are heavily urbanized and have associated industrial development (Figure 2). Figure 2: Coastal populations and shoreline degradation (Source: UNEP 2002, Data from Burke and others 2001 and Harrison and Pearce 2001) There is a rich coastal and marine biodiversity associated with the fringing and patch coral reefs and mangrove forests in Tanzania and Mozambique (Figure 1). Mangrove areas in those countries total 6,483 km2 while, in Tanzania, fringing reef platforms and patch reefs occur on over 80 percent of the coast. Coral communities also occur on the Maputoland Reef in KwaZulu Natal, South Africa. Most reefs were severely affected by the coral bleaching event of 1998 and there was further mortality in 2002. Patchy infestation by crownof-thorns starfish (COTS) has also been reported. The Agulhas Current Large Marine Ecosystem (LME) has an enhancing effect on biodiversity which extends from Tanzania to well along the South African coast. The estuaries of Tanzania and Mozambique support penaeid prawn fisheries while, on the reef shores, artisanal and subsistence fishing are major activities. In Tanzania, areas of coastal forest with high levels of endemism occur over about 350 km2 as fragments of a formerly extensive lowland forest. The west coast has no significant coral reef development, with only a few coral species reported from Angola (Figure 1). Mangrove is confined to Angola where 1,100 km2 are recorded. It is characterized by productive upwelling systems between Cape Agulhas in South Africa and southern Angola – the Benguela Current LME (Box 6). It has relatively low diversity but makes an important contribution to the total African, and global, fish catch, with epipelagic species including the South African pilchard and the Cape anchovy. Mangrove forests provide valuable ecosystem servicesThe Zambezi delta, Mozambique, showing the extensive development of mangrove (dark green) between the distributary's channels(Source: NASA 2000) There are significant coastal and offshore hydrocarbon resources. Angola has by far the majority of Southern Africa’s estimated crude reserves – 5.4 thousand million barrels, mostly located in deep water. Reserves of natural gas, also largely offshore, make up about 2.5 per cent of Africa’s total. Reserves have been discovered in Angola (1.6 x 1012 cubic feet); Mozambique (4.5 x 1012 cubic feet); Namibia (2.2 x 1012 cubic feet); South Africa (780 x 109 cubic feet) and Tanzania (800 x 109 cubic feet), where there are commercial reserves under production around the island of Songo-Songo. Rivers may transport large amounts of sediment to the seaPlumes of suspended sediment discharged to the Atlantic Ocean from the Gariep River at the boundary of Namibia and South Africa. The river has been the conduit for alluvial diamonds that are being dredged and mined in the coastal zone (Source: NASA 2000) Diamond mining from coastal sand dunes and by dredging inshore seabed sediments is a major industry in Namibia and western South Africa. The minerals have been derived over time from the diamond-bearing volcanic rocks exposed in the catchment of the Gariep (formerly Orange) River. In coastal sediments on the Indian Ocean shores of South Africa and Mozambique, there are commercially viable titanium and zirconium minerals, also derived from the hinterland. There are three coastal UNESCO World Heritage sites in South Africa. The Greater St Lucia Wetland Park has critical habitats for species from marine, wetland and savannah environments, and has exceptional species diversity. (Southern Africa and coastal and marine environments)

The Benguela Current Large Marine Ecosystem (BCLME) Programme

The Benguela Current LME is one of the world’s most productive marine environments. In 2000, the total fish catch of the region was 1,166 000 t. The fishing industry has become an economic mainstay, contributing 10 percent of GDP in Namibia, 4 percent in Angola and 0.37 percent in South Africa. The continental shelf is also rich in oil, natural gas and diamonds. Oil production contributes 70 percent of Angolan GDP, and the Kudu gas fields in Namibia hold some of the largest reserves in western Africa. The marine diamond mining industry in Namibia and South Africa yields close to a million carats of diamonds each year. The exceptional natural beauty, biodiversity and cultural attributes of the BCLME already attract large numbers of tourists, particularly in South Africa, and tourism has the potential to grow substantially.

The ecosystem faces accelerating threats which, if leftunchecked, could threaten vital economic and ecological values. The primary threats include habitat loss and pollution – particularly in areas adjacent to urban centres – and increasing exploitation of straddling fish stocks, concerns exacerbated by the lack of a coordinated regional management framework. There is also the recognition that oil and gas exploration and production, and diamond mining in and around critical marine habitats, will have to be undertaken in an environmentally safe manner to minimize impacts. In addition, the BCLME is characterized by a high degree of environmental variability, manifest in fluctuations in the abundance and distribution of marine living resources. Global climate change has the potential to influence this variability. The transboundary nature of these issues demands regional cooperation for their effective management.

In 1999, Angola, Namibia and South Africa signed a Strategic Action Programme, identifying strategies and priority actions required to protect the BCLME. In 2002, the Benguela Current Large Marine Ecosystem (BCLME) Programme was officially launched. The Programme aims to integrate management, sustain development and protect and conserve the ecosystem. The regional initiative is funded by the Global Environment Facility (GEF), which is contributing US$15.2 million, complementing an investment of approximately US$16 million by the three countries. The initiative aims to lay the foundation for a long-term collaborative management system, overseen by a regional management organization, to be known as the Benguela Current Commission.

From its inception in March 2002 to the end of 2004, the Programme had instituted 60 projects worth US$4.7 million. These were designed to address transboundary environmental problems and contribute to the integrated and sustainable management of the BCLME. The Programme is regarded as a concrete and constructive initiative towards the New Partnership for Africa’s Development (NEPAD).

Endowments and opportunities

The combination of coastal attractions and unique wildlife presents a powerful resource for the long term if utilized with care. Nearly all of the coastline holds some sort of attraction. With careful management, the value of the assets underpinning such attractions can increase. Travel and tourism are already major foreign exchange earners in Southern Africa and much of the income is generated in coastal areas, providing substantial employment opportunities for women as well as men. In South Africa, travel and tourism in 2005 is expected to generate US$30.3 thousand million of economic activity (total demand), in Namibia, US$1,004.4 million and in Tanzania, US$1,858.4 million, accounting for 9.7 percent of its GDP and 7.7 percent of total employment.

The mangrove forests present opportunities for improving the livelihoods of coastal people and contributing to the alleviation of poverty. They are a rich source of fuel, building poles, and materials for boat making, and provide nectar for large populations of bees. With effective conservation and replanting programmes, perhaps supported by ecotourism, these resources could be harvested on a sustainable basis, maintaining supplies while preserving their important ecological functions.

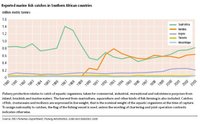

Total marine fisheries production declined from 1,556,000 tonnes (t) in 1988 to 1,289,000 t in 2000, the contribution to the world total declining from 11.0 to 7.2 percent. However, despite this trend some countries have increased their production (Figure 3). The overall declining trend is a continuation of that reported for the period 1972-97 and is part of the global trend (Pauly and others). Approximately half the finfish catch is taken by South Africa, and more than half the crustacean catch is taken by Mozambique, where catch value is dominated by the shallow-water penaeid prawns. Despite the declining trends in marine fish production, fishery commodity exports over the period 1988-2000 rose in value from US$200 million to US$892 million, while imports declined from US$224 million to US$195 million. In South Africa, coastal goods-and-services in 1998 were estimated to be worth about US$29,000 million or 37 percent of the GDP; this figure incorporated about US$175 million in terms of benefits to subsistence fishermen. The commercial fishery was worth about US$270 million and the recreational fishery US$200 million.

Combined freshwater and marine aquaculture production rose from 4,000 t in 1988 to 11,000 t in 2000 . The seaweed Eucheuma is cultivated, mainly by women, on intertidal platforms mainly in Zanzibar, Tanzania, with a production of 7,000 t in 2002 (Figure 3). Cultivation is slowly spreading to mainland Tanzania and Mozambique. Seaweed farming represents an opportunity for coastal villagers, and especially women, to improve their incomes.

Hydrocarbon resources are making an increasingly strong contribution to the economy. Over the last decade or so, the focus of oil and gas exploration has shifted offshore to the coastal waters, where there are now many successful production ventures. Angola is the only significant oil producer. Overall, by early 2004, Angola’s production reached nearly 950,000 barrels per day (bbl/d) and this is expected to double by early 2008, with new deep-water production sites. South Africa’s production is also from offshore fields which, by late 2003, yielded more than 60,000 bbl/d. Much of the gas associated with oil production is currently flared or reinjected. In Tanzania, production on the island of Songo-Songo is gathered from on and around the island and transported via a 225-km pipeline to Dar es Salaam where it provides fuel for electricity generation. Development and production present considerable local employment opportunities, though mostly for men.

The value of the alluvial diamond industry in Namibia and western South Africa was estimated at US$625 million in 1998 (Government of South Africa 1998).

Challenges faced in realizing development

The environmental issues and threats relating to the realization of development opportunities are addressed within the framework of the Nairobi Convention (by Tanzania, Mozambique and South Africa) and the Abidjan Convention (by Angola, Namibia and South Africa). These MEAs focus on coordinated protection and enhancement of the marine environment and coastal zones. Land-based activities impacting the coastal and marine resources in the countries flanking the Indian Ocean are being addressed through the Nairobi Convention as part of the GEF-funded WIO-LaB project.

The coastal environment is vulnerable and is being degraded by the current levels of development. Critical ecological functions are being undermined, including those provided by mangrove swamps, coral reefs, rivers and estuaries, which protect and stabilize coastlines, and provide sediments for beaches and nursery areas for fish and prawns. These changes, ironically brought about development activity, are increasing the vulnerability of human populations, particularly those in low-lying coastal areas. Such vulnerability will be exacerbated by sea-level rise, storm surges and tsunamis.

Population growth, combined with migration to large coastal cities, will form one of the major challenges for physical planning and policy formation to protect coastal areas. On the eastern coasts, the population is growing at 5 to 6 percent annually, due to births and migration from inland rural areas, and coastal poverty levels are high. The traditional cultural and religious beliefs of the indigenous communities relating to the marine environment and its resources are being lost as population densities increase and people move in from other areas, thus diminishing a vital management resource.

In Tanzania and Mozambique, the degradation of the coral reef resources due to increasing population pressures and coral bleaching is one of the most important management issues. Bleaching has caused the decline of 30 percent of the reefs, and the threats posed by a growing population are probably slowing their recovery. In Mozambique and southern Tanzania, there have been increased rates of reef erosion, due in part to the bioerosion of dead coral tables and plates. A patchy but widespread increase in COTS infestation was recorded in 2003 and 2004 in Tanzania. Much of the damage to the reef ecosystems is coming from fisheries exploitation. Specific threats include excess harvesting (in part by migrant fishers), the use of destructive gears such as beach seines and gill nets, and bomb fishing that damages juvenile fish populations and vulnerable species. In Tanzania, by far the most destructive type of fishing is dynamiting, which has been practised since the 1960s. In the 1980s and 1990s, dynamite blasts reached epidemic rates. Recent management initiatives there have already had a significant positive impact on the coral reef environment. Resource users, particularly fishing communities, have been increasinglyinvolved, enhancing their environmental awareness. Mangrove areas continue to be under threat from pollution and coastal development, notably aquaculture and the construction of salt pans. The overall rate of deforestation in Mozambique is estimated at 18 km2 per year.

In South Africa, the once abundant, easily accessible, shallow sub-tidal invertebrate resources, such as the southern rock lobster and the abalone, have been reduced by heavy commercial and in part illegal exploitation. High prices obtainable for abalone in eastern Asia have exacerbated the pressure on this species and increased poaching. The shallow-water prawns of Mozambique have long been the targets of artisanal fisheries and a major tourist attraction in local restaurants (Box 1). With the possible exception of sea cucumbers in Mozambique, there are few, if any, other large invertebrate stocks which remain to be profitably exploited. In contrast to most western African countries, Namibia’s policy of fisheries management since independence has generated economic and social benefits to the country.

Constraints to coastal aquaculture development include the lack of sheltered waters and the environmental degradation of coastal environments, such as mangrove forests. It should also be realized that aquaculture and mariculture are energy-consuming, rather than energy-producing, processes. While there might be employment opportunities, the products, whether they be mussels, prawns, abalone or fish, tend to be beyond the means of poor communities.

Mineral extraction from dunes and the seabed is controversial, given the environmental degradation to which it can lead. On the east coast of South Africa, the mitigation of these impacts constitutes a sub-industry. The exploitation of mineral resources is a comparatively shortterm operation and one which needs to be carefully managed in order to mitigate any short- or long-term environmental impacts. There is also a need for responsible management in order to maximize the benefits to the people of the country and to allow investment of profits in longer-term sustainable developments. In Tanzania, the extraction of live coral for lime burning is a widespread activity which can have highly destructive effects on reef habitats.

Physical shoreline change, including coastal erosion, is another common issue, though its causes include natural forcing as well as human interventions and pressures. In Tanzania, shoreline change – accretion as well as erosion – impacts particularly on tourism infrastructure. Erosion has led to the demolition of beach hotels on low-lying beach plains at Kunduchi, near Dar es Salaam. Attempts have been made to stabilize shorelines by the installation of groynes. It is anticipated that coastal erosion will increase with sea-level rise associated with global climate change.

Further reading

- Alder, J. and Sumaila, U.R., 2004. Western Africa: A fish basket of Europe past and present. Journal of Environment and Development. 13(2), 156-78.

- EIA, 2005. Country Analysis Briefs. Energy Information Administration.

- FAO Fisheries Department

- Government of South Africa, 1998. Coastal Policy Green Paper: Towards Sustainable Coastal Development in South Africa.

- IPCC, 2001. Watson, R.T. and the Core Writing Team (eds). Climate Change 2001: Synthesis Report.A Contribution of Working Groups I, II, and III to the Third Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Kairu, K. and Nyandwi, N. (eds. 2000). Guidelines for the Study of Shoreline Change in the Western Indian Ocean Region. IOC Manuals and Guides No. 40. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural, Paris.

- Obura, D., 2004. Biodiversity Surveys of the Coral Reefs of the Mnazi Bay Ruvuma Estuary Marine Park. IUCN – The World Conservation Union Eastern Africa Regional Office, Nairobi.

- Obura, D., et al., 2004. Status of Coral Reefs in East Africa 2004: Kenya, Tanzania, Mozambique and South Africa. In Status of Coral Reefs of the World: 2004 (ed.Wilkinson, C.),Vol. 1.

- Taylor, M., Ravilious, C. and Green, E.P., 2003. Mangroves of East Africa. UNEP-WCMC Biodiversity Series No. 13.

- UNEP, 2001. Eastern Africa Atlas of Coastal resources,Tanzania. United Nations Environment Programme, Nairobi.

- UNEP, 2002a. Africa Environment Outlook: Past, Present and Future Perspectives. United Nations Environment Programme, Nairobi

- UNEP, 2006. Africa Environment Outlook 2

- Wagner, G.M, 2004. Coral reefs and their management in Tanzania. Western Indian Ocean Journal of Marine Science. 3(2), pp. 227–243.

- UNEP/GPA, 2004. Shoreline Change in the Western Indian Ocean Region: An Overview. Report prepared by Western Indian Ocean Marine Science Association (WIOMSA) for United Nations Environment Programme / Global Programme of Action, The Hague.

- UNEP-WCMC, 2000. Marine Information. United Nations Environment Programme’s World Conservation Monitoring Centre.

- UNESCO, 2005. World Heritage Centre – World Heritage List. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization.

- Wagner, G.M, 2004. Coral reefs and their management in Tanzania. Western Indian Ocean Journal of Marine Science. 3(2), pp. 227–243.

- WIO-LaB, 2005. Addressing Land-based Activities in the Western Indian Ocean.

- WTTC, 2005. Country League Tables – Travel and Tourism: Sowing the Seeds of Growth – The 2005 Travel & Tourism Economic Research. World Travel and Tourism Council, London.

|

|

| Disclaimer: This article is taken wholly from, or contains information that was originally published by, the United Nations Environment Programme. Topic editors and authors for the Encyclopedia of Earth may have edited its content or added new information. The use of information from the United Nations Environment Programme should not be construed as support for or endorsement by that organization for any new information added by EoE personnel, or for any editing of the original content. |