Sub-regional scenarios for Africa's future: Central Africa

Contents

Introduction

The doors we open and close are our choice. (Source: J.C. Mohamed-Katerere) Forest and woodland resources in Central Africa are an important environmental resource that can play a central role in economic development. Owing to its vastness, the protection of this resource is not only significant to the countries within the sub-region, but also to the rest of Africa and the world. Central African forests and woodlands play a crucial role in carbon sequestration. The full costs of deforestation for the sub-region are not completely understood. Deforestation has multiple negative impacts: it threatens biodiversity (Sub-regional scenarios for Africa's future: Central Africa) , water and energy resources, and contributes to trace-gas emissions. It may contribute to changes in ecosystem function including biogeochemical cycles and climate patterns through altering local rainfall and hydrological processes, and desertification. The degradation of vegetation cover has caused some parts of Central African countries that were previously under forest to change to savannah grasslands and degraded savannah. It will also have direct economic costs including the loss of future wood for forest industry and loss of biological diversity. The current and future state of the Congo basin forest reserves will reflect the overall environmental health in the sub-region, and will affect the development opportunities available.

This resource, however, is under threat from a variety of socioeconomic factors. Deforestation in the sub-region is closely tied to demographic conditions; the highest levels of deforestation have occurred in countries with higher population growth rates and higher population densities. Human settlement and economic activities result in infrastructural development (roads), increased agriculture, bush fires, overharvesting of timber and non-timber forest products (NTFPs); all these activities impact on environmental change. Chapter 6: Forests and Woodlands (Sub-regional scenarios for Africa's future: Central Africa) presents an overview of how forest cover is changing in Central Africa, and the most important drivers of this change. As discussed in Chapter 12: Environment for Peace and Regional Cooperation (Sub-regional scenarios for Africa's future: Central Africa), conflict and poor governance have exacerbated environmental change, and improved cooperation offers important opportunities for environmental sustainability and expanding the range of available opportunities.

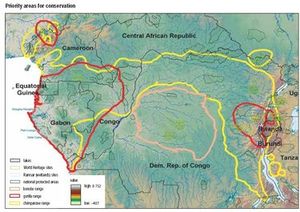

(Source: UNEP/DEWA/ GRID 2001; Data sources: Great apes ranges: Instituto Ecologia Applicata (IEA) Rome 1998, African Mammals Databank (AMD) for the Directorate-General for Development (DGVIII/A/1) of the European Commission. Project No, B7-6200/94-15/VIII/ENV; Ramsar sites, World Heritage sites and national protected areas: UNEP-WCMC; Digital Elevation Model of the Land: Environmental Systems Research Institute (ESRI) Base maps (country boundaries, lakes and rivers): Digital Chart of the World. Projection: Geographic)

Since Africa Environment Outlook 1 (AEO-1), there have been several conservation-focused initiatives that have significantly contributed to forging a new vision within the Congo basin on development and implementation of transboundary conservation programmes. Some of these initiatives give snapshots of scenarios presented at the time. The main milestones have been:

- A strategic plan called the “Plan de Convergence” for the implementation of the Yaoundé Declaration was finalized and endorsed by the Central Africa Forests Commission (COMIFAC). This involved the compilation of the different action plans identified by the member states. Priority activities were later identified from the Plan de Convergence.

- Sustainable financing of conservation work has become a priority for Central African governments and partners.

- The Congo Basin Forest Partnership (CBFP) was launched to help conserve 29 protected areas, and promote sustainable forestry and community-based conservation in 11 priority landscapes spanning the Congo basin. Figure 1 shows areas of conservation importance.

The following scenario exercises help make an assessment of how future trends may be affected by policy choices.

Market Forces scenario

In this scenario, the existing trend of deforestation and degradation of forest areas continues, as a result of both the need for more land for human settlement and agriculture, and the drive to exploit forest resources (mainly timber) to boost economic development, particularly export earnings.

The rate of deforestation and land conversion, however, slows down, due to forestation initiatives and the gradual implementation of existing multilateral environmental agreements (MEAs) to use forests in a sustainable manner. Increased investment in the tourism sector, and in particular in ecotourism, provides additional incentives to conserve forests, though this is offset to some extent by the increase in land pressures. In order to secure the future of forested areas, as well as to spread the benefits of their conservation more widely, communities living in the forests and surrounding areas are encouraged to take part in their management, sustained use and conservation. This, too, contributes to slowing down the rate of deforestation. The world market demands for medicinal plants and other NTFPs increase and this too serves as a conservation incentive. The emergence of global carbon markets encourages Central African countries to protect forest resources and to make economic benefits from these resources.

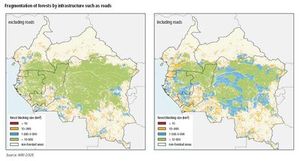

However, in order to seize the opportunities in these new sectors (including tourism, pharmaceuticals and NTFPs) and increase profits, a new level of investment in forest areas is required. The expansion of physical infrastructure is an important aspect of this, and it has the added benefit of bringing new opportunities to forest dwellers. However, road development also leads to fragmentation of forest (see Figure 2). Trade liberalization, with appropriate technologies, improves the quality of logging. The industrial and artisan exploitation of wood increases the pressure on forest resources. The strategies to protect the forest, and ensure rational management of forest resources, are difficult to apply, in spite of the number of conventions and initiatives developed to this effect.

Policy Reform scenario

In the Policy Reform scenario, dependence on biomass, the traditional fuel in Central Africa which supplied 60 percent of all energy requirements at the end of the 20th century, is reduced, because people have more energy choices. Public and private power utilities compete to provide electricity to both urban and rural areas, making such services more reliable. The result is that the rate of deforestation due to fuelwood demand and charcoal production is reduced considerably. Policy and legal reforms promote involvement of the local population and defines, with their participation, the conditions of their involvement. Local populations participate in the conservation of forest resources, and obtain a share of benefits from this. Forest industries have to utilize forests resources within this new legal framework. New technologies are developed and are introduced in logging.

A close relationship between knowledge and policy evolves. Research work takes into account the concerns of local users and other stakeholders, including managers of forest, through inclusive priority setting. New protected areas are created as a result. Also, there is an increased focus on the opportunities that markets for environmental services can bring. Governments recognize and set up policies to encourage benefits from carbon commoditization. There is a deliberate effort to strengthen the existing forestry management programmes such as Central Africa Regional Programme on the Environment (CARPE), COMIFAC and Central African Protected Areas Network (RAPAC) for regional cooperation in transboundary forest management.

Fortress World scenario

In the Fortress World scenario, deforestation and degradation of forest areas generally continue at high rates. However, there are pockets of restoration.

The elite, tempted by the high demand for forest products in the global market, act as resource extractors, and overexploit the forest resources. Ironically, they safeguard some forest areas under international pressure. Some of the remote forest areas, away from population pressure, are also saved. Commercial exploitation of medicinal plants contributes to accelerated deforestation. Given limited opportunities, poor people fall back on extensive use of the forest resources to which they have access, as a source of energy, food and shelter. Forest wood is also used commercially for the production of crafts for trade.

The increase in the poverty of farmers, and the fall in prices of agricultural produce, leads to more pressure on the forests, which are the primary sources of revenue. Unregulated logging increases. Industries which are involved in logging do not take the regulations into account and, engage in illegal logging activities. The export of roundwood means that the full potential earnings of timber products are not realized. There is a boom in the development of NTFPs, as well as an increase in their domestic use.

The consequences of deforestation and desertification are disastrous for the Sahelian areas (northern Cameroon, Central African Republic and Chad). The creation and strengthening of forestry training institutions at the national and sub-regional levels, to provide qualified human power and technology to the forestry department, is an emerging challenge for Central African countries, but this is not a priority for the elites. The option of strengthening forestry sub-regional cooperation by harmonizing legislation and creating and managing transboundary protected areas for sustainable development is not taken up and in general environmental and human wellbeing continue to deteriorate.

Great Transitions scenario

In the Great Transitions scenario, real recognition is given to sustainable uses of forest resources for medicinal and other purposes, and opportunities for improving livelihoods are directly sought. This is balanced with environmental objectives. Consequently, sensitive and important habitats are protected, and systems for the sustainable use of biodiversity outside these protected areas are established.

Stakeholders, including users and owners, are brought into management. Education and the promotion of a shared value system are key focuses. Communities are environmentally aware, and are empowered to care for the Earth. This is made possible by moving from a restrictive legal regime that focuses on command-and-control regulations to one that is more empowering and consistent with the Convention on Biological Diversity and promotes the fair and equitable sharing of benefits arising from the use of biodiversity. Areas of forests increase and forest quality improves, as a result of the realization of the true value of forest resources, and improved forest management.

Integrated and sustainable development management ensures minimal degradation of the human environment system. Human and environmental vulnerability are minimized. The capacity of non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and civil society is enhanced, and they are empowered to play a more significant role in environmental management. Higher protection of the environment and of fragile ecosystems is a prime focus for all stakeholders in the forest industry.

This sub-region continues with the development and use of light technology by trained people, in order to make rational use of forest resources. The existence of research institutes, and training in forestry (wood-based occupations), makes Central Africa a specialist in forestry training and research. All countries ratify and implement the main conventions regarding sustainable management of the environment and local, national and sub-regional actions reflect policies directly targeting New Partnership for Africa's Development (NEPAD) environment initiatives.

Policy lessons from the scenarios

The Central African forest basin is undergoing fundamental change as a result of, among other things, logging. Governments of Central Africa, donor agencies and private forestry companies must act urgently to address the rapid acceleration of forestry operations in the basin and the negative impacts provoked by these activities.

Investment now in establishing systems of proper forest management will avoid huge costs in the future, including the forgone benefits of squandered forest resources, the costs of resource restoration and rehabilitation, the loss of wildlife and its potential for alternative revenue generation, and the social costs associated with all of the above. From the various scenarios, a mix of policy actions may be appropriate. Specific policy action may focus on:

- Establishing forest zoning through an assessment of concessions based on zoning categories which include protected areas, sustainable use areas, zones designated for agriculture or other land uses.

- Promoting transparency in the allocation of forestry concessions and revenue generation.

- Improving forestry practices to reduce undue damage to the remaining forest, reduce timber waste, and protect the regenerative capacity of the forest.

- Institutionalizing measures, especially on government land, to ensure that endangered species are protected on their lands, and that export of wildlife products from their concessions is not facilitated by their operations.

- Enhancing local participation in forest management, in which local interests and cultures are safeguarded.

- Designating new protected areas in the forest, especially in light of the uncertainty of the sustainability of logging practices, and ensuring effective management of these.

- Accelerating research on the sustainability of forestry operations in the basin (including autecology – the characteristics of individual species, the life history of commercial species, regeneration dynamics).

A monetary value can be attached to environmental benefits coming from forestry activities aimed at reducing carbon emissions. Central African countries can find secure opportunities to convert this into monetary gains at the carbon world markets. There is a need to strengthen capacity-building in the assessment of the economic value and potential of Central African forest resources to this end.

Making these changes a reality requires political will of all governments in Central Africa. Donor agencies must assist in providing technical and financial support. Private companies must commit to responsible, sound practice and assume more of the costs of their impacts. With these stakeholders working in concert, the forest of the Central African basin may continue to yield biological, economic and social benefits well into the future. The window of opportunity to do this is very short. In five years it will be difficult to establish sustainable management schemes in Central Africa. In much of the forest, it will simply be too late.

Further reading

- FAO, 2005b. State of the World’s Forests 2005. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome.

- UNEP, 2006. Africa Environment Outlook 2.

- WCMC, 1992. Global Biodiversity: Status of the World Living Resources. World Conservation Monitoring Centre.Chapman and Hall, London.

- WWF, 2005. Central African countries commit to protect the natural wealth of their forests. Gift to the Earth 98 Summary.

- WRI in collaboration with UNEP and UNDP, 1994. World Resources Report 1994–95: People and the Environment.World Resources Institute in collaboration with United Nations Environment Programme and United Nations Development Programme World Resources Institute, Washington, D.C.

|

|

| Disclaimer: This article is taken wholly from, or contains information that was originally published by, the United Nations Environment Programme. Topic editors and authors for the Encyclopedia of Earth may have edited its content or added new information. The use of information from the United Nations Environment Programme should not be construed as support for or endorsement by that organization for any new information added by EoE personnel, or for any editing of the original content. |