Spinner dolphin

The Spinner dolphin (Stenella longirostris), a marine mammal in the family of oceanic dolphins, gets itsname from the spinning behavior it shows when it leaps out of the water. This cetacean species lives in schoolsshowing a dominance hierarchy and displays complex interactions among individuals. S. longirostris also engages in intricate echolocation underwater acoustics. Spinner dolphins attract tourists for dolphin watching. The species is of special interest for scientific investigation because of its remarkable capacity to learn.

|

Conservation Status: |

|

Scientific Classification Kingdom: Animalia |

|

Common Names: |

Contents

Physical Description

The spinner dolphin is six to seven feet long and exhibits a three part colour pattern on its body. The pattern consists of a dark gray back, a pearl-gray side panel and a white belly. Males possess a postanal hump and are generally larger than the females. Spinner dolphins that live farther away from land are morphologically different from those that live close to land.

The small and slender spinner dolphin varies geographically in coloration and size, but can be identified by its relatively long, slender beak and triangular dorsal fin. The most common color pattern is three-part: dark grey on the back, lighter grey along the sides, and white or very light grey underneath. A darker grey stripe runs from the eye to the flipper, bordered above by a narrow, light line.

Reproduction

Spinner dolphins are polygynandrous. Mating in spinner dolphins appears to be promiscuous, and like many small dolphins, true courtship behavior can be observed, such as mutual caressing between the male and female.The male senses when the female is ready to mate and pursues her. Mating happens within the school with no real mate selection. The breeding system may vary geographically, with some populations showing a greater degree of polygyny than others.

Spinner dolphins mate when their hormone levels are high, which is one or two times a year. The male swims upside down underneath the female and inserts his penis into the female's reproductive tract. Females reach sexual maturity between four and ten years, while males reach sexual maturity between seven and twelve years. Adult females give live birth to one calf every two or three years. The gestation period averages 10.6 months. Females nurse their calves for a minimum of seven months up to two years, and they form a bond that lasts a lifetime.

Behavior

Spinner dolphins move about the oceans in schools; groups that vary in size from just a few dolphins to over a thousand. They commonly school with other species such as pantropical spotted dolphins, or small toothed whales. In such schools, spinner dolphins are known to undertake migrations, following prey or warm water currents. In Hawaii, spinner dolphins usually spend their days resting in shallow bays near deep water, and then move offshore at dusk and feed as they move substantial distances along the shore.

Spinner dolphins may occur in schools with as many as 1000 individuals, but it is common to have 200 or fewer to a school. They are very social with each other and with other species of ocean dwellers. Spinner dolphins have been known to associate with spotted dolphins as well asyellowfin and skipjack tuna. Spinner dolphins rest in shallow waters, usually inlets. They tend to go back to the same area each day. When they are done resting, they quickly swim out to the deep area to feed on the vertically migrating fauna. When they are in the deep, darker waters, they are more susceptible to predation.

There is a dominance hierarchy within the schools of spinner dolphins. It is sustained by a descending order of threats and by behaviors that involve caresses. Threats are usually a simple nudge or abrupt gesture. These hierarchies are active when the school is in an enclosed area, and not in the open sea.

Spinner dolphins communicate with each other by echolocation, caressing each other, and using aerial patterns. They are most active when they have just finished resting.

The spinning jump is the trademark jump for this species. Spinner dolphins may rotate up to seven times while they are in the air! They do this most frequently at night. The purpose of the energetic spinning behavior of the spinner dolphin is not known. The back-flop or belly-flop that occurs when they fall back into the water produces a large cloud of bubblesthatmay act as an echolocation target, to allow a widely dispersed school of dolphins to communicate. Another theory is that the spinning may dislodge hitch-hiking remoras, or the spinning may, at times, simply be play.

Distribution

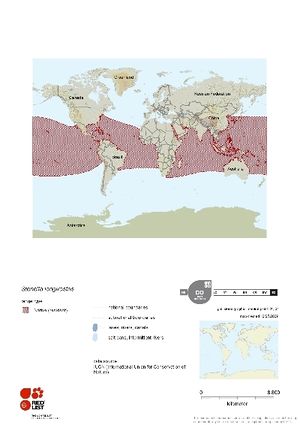

Spinner dolphins are found in the tropical and subtropical waters in the Atlantic, Indian and Pacific oceans. They can also be found in some warm temperate areas. Spinner dolphins often occur near islands.

At present, four subspecies are recognised:S. l. longirostris(Gray's spinner dolphin), which occurs in all tropical seas;S. l. orientalis(Eastern spinner dolphin), found in open waters of the eastern tropical Pacific;S. l. centroamericana(Costa Rican or Central American spinner dolphin), which inhabits continental shelf waters off western Central America and southern Mexico; andS.l. roseiventris, (dwarf spinner dolphin) which inhabits shallow waters of Southeast Asia. Oceanic tropical and subtropical zones in both hemispheres. Limits are near40ºN and 40ºS.

Habitat

Stenella longirostrisis mostly pelagic, and the species spends time in both shallow waters and deeper water farther from land. The spinner dolphin is typically thought of as a tropical high seas species, but it also inhabits shallow reef areas, coastal areas,and warm subtropical temperate waters.

Predation and Feeding Habits

The pelagic spinner dolphin is a carnivore that feeds primarily on small fish, squids and shrimps, and divesdown to depths of 300 meters to catch its prey. The dwarf spinner dolphin feeds on reef fishes and other benthic organisms. Spinner dolphins use their excellent communication skills to allow them to hunt in groups. They canproduce ultrasonic noise that stuns, or kills, fish making them easier to capture.

Conservation Status and Threats

The IUCN classifies this species as Data Deficient. Spinner dolphins in the eastern tropical Pacific have been killed incidentally since the early 1960s by tuna purse seine fisheries. They were caught in such large numbers that the population ofS. l. orientaliswas reduced to less than one third of its original size. Following raised awareness of the number of dolphins killed in tuna purse seine fisheries, measures were implemented to reduce dolphin by-catch. Today spinner dolphins continue to be killed in this way, although in greatly reduced numbers. However, continued chase, capture and release of large numbers in the fishery may be preventing the population from recovering.

In Sri Lanka and the Philippines, large numbers of spinner dolphins have also been captured in gillnets and killed by harpoons for the past 20 years, and local harpoon fisheries exist in several more locations throughout the world. Incidentally captured dolphins are consumed by local people, or used as shark bait, and this has led to the development of markets and fisheries directed at dolphins. The takes in these fisheries may be unsustainable.

The major threat to spinner dolphins is by-catch entrainment in tuna nets. There is also habitat destruction in some areas due to tourism infrastructure development. Spinner dolphins are protected in some countries. In the United States, special efforts have been made to monitor and reduce deaths due tothe tuna industry.

References

- Encyclopedia of Life. 2010. Stenella longirostris, Spinner dolphin

- IUCN Red List

- Margaret Klinowska. 1991. Dolphins, Propoises, and Whales of the World: The IUCN Red Data Book. International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources, United Kingdom

- Kenneth S.Norris. 1991. Dolphin Days: The Life and Times of the Spinner Dolphin. W.W. Norton & Company, New York, London

- William F.Perrin. Spinner Dolphin, in Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals pp. 1173–1175. ISBN 978-0-12-551340-1

- K.P.N.Shuker. 2001. The Hidden Powers of Animals: Uncovering the Secrets of Nature. London: Marshall Editions Ltd. 240 p.

- Perrin, W.F. (1998) Stenella longirostris. Mammalian Species, 599: 1 - 7.

- CITES (August, 2007)

- Convention on Migratory Species (August, 2007)

- Perrin, W.F. (2002) Spinner dolphin. In: Perrin, W.F., Würsig, B. and Thewissen, J.G.M. Eds. Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals. Academic Press, London.

- Reeves, R.R., Smith, B.D., Crespo, E.A. and di Sciara, G.N. (2003) Dolphins, Whales and Porpoises: 2002-2010 Conservation Action Plan for the World's Cetaceans. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge, UK.

- Perrin, W.F., Dolar, M.L.L. and Robineau, D. (1999) Spinner dolphins (Stenella longirostris) of the western Pacific and Southeast Asia: pelagic and shallow-water forms. Marine Mammal Science, 15: 1029 - 1053.

- Culik, B.M., Würtz, M. and Gerkman, B. (2002) Review on Small Cetaceans: Distribution, Behaviour, Migration and Threats. Convention on Migratory Species, Bonn, Germany.

- Würsig, B. (2002) Courtship behaviour. In: Perrin, W.F., Würsig, B. and Thewissen, J.G.M. Eds. Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals. Academic Press, London.

- Perrin, W.F. and Mesnick, S.L. (2003) Sexual ecology of the spinner dolphin, Stenella longirostris: geographic variation in mating system. Marine Mammal Science, 19: 462 - 483.

- Gerrodette, T. and Forcada, J. (2005) Non-recovery of two spotted and spinner dolphin populations in the eastern tropical Pacific Ocean. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 291: 1 - 21.

- Reeves, R.R. (2002) Conservation efforts. In: Perrin, W.F., Würsig, B. and Thewissen, J.G.M. Eds. Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals. Academic Press, London.

- Perrin, W.F. (1999) Selected examples of small cetaceans at risk. In: Twiss, J.R. and Reeves, R.R. Eds. Conservation and management of marine mammals. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, D.C.

- Banks, R. C., R. W. McDiarmid, A. L. Gardner, and W. C. Starnes. 2003. Checklist of Vertebrates of the United States, the U.S. Territories, and Canada

- Banks, R. C., R. W. McDiarmid, and A. L. Gardner. 1987. Checklist of Vertebrates of the United States, the U.S. Territories, and Canada. Resource Publication, no. 166. 79

- Felder, D.L. and D.K. Camp (eds.), Gulf of Mexico–Origins, Waters, and Biota. Biodiversity. Texas A&M Press, College Station, Texas.

- Gray, J.E., 1828. Spicilegia zoologica; or original figures and short systemic descriptions of new and unfigured animals, p. 1. Treuttel, Wurtz and Co. and W. Wood, London, 8 pp.

- Hershkovitz, Philip. 1966. Catalog of Living Whales. United States National Museum Bulletin 246. viii + 259

- IUCN (2008) Cetacean update of the 2008 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.

- Jefferson, T.A., S. Leatherwood and M.A. Webber. 1993. Marine mammals of the world. FAO Species Identification Guide. Rome. 312 p.

- Klinowska, Margaret. 1991. Dolphins, Propoises, and Whales of the World: The IUCN Red Data Book. International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources, United Kingdom.

- Mead, James G., and Robert L. Brownell, Jr. / Wilson, Don E., and DeeAnn M. Reeder, eds. 2005. Order Cetacea. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference, 3rd ed., vol. 1. 723-743

- Norris, Kenneth S. 1991. Dolphin Days: The Life and Times of the Spinner Dolphin. W.W. Norton & Company, New York, London.

- Norris, Kenneth S., Bernd Wursig, Randall S. Wells, and Melaney Wursig 1994. The Hawaiian Spinner Dolphin. University of California Press, Berkely, Los Angeles, London.

- North-West Atlantic Ocean species (NWARMS)

- Perrin, W. (2010). Stenella longirostris (Gray, 1828). In: Perrin, W.F. World Cetacea Database. Accessed through: Perrin, W.F. World Cetacea Database at http://www.marinespecies.org/cetacea/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=137109 on 2011-02-05

- Perrin, William F. 1998. Stenella longirostris. Mammalian Species, no. 599. 1-7

- Rice, Dale W. 1998. Marine Mammals of the World: Systematics and Distribution. Special Publications of the Society for Marine Mammals, no. 4. ix + 231

- Shuker, KPN. 2001. The Hidden Powers of Animals: Uncovering the Secrets of Nature. London: Marshall Editions Ltd. 240 p.

- UMMZ Animal Diversity Web. World Wide Web electronic publication. , version (08/2009).

- Wilson, Don E., and DeeAnn M. Reeder, eds. 1993. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference, 2nd ed., 3rd printing. xviii + 1207

- Wilson, Don E., and F. Russell Cole. 2000. Common Names of Mammals of the World. xiv + 204

- Wilson, Don E., and Sue Ruff, eds. 1999. The Smithsonian Book of North American Mammals. xxv + 750

- van der Land, J. (2001). Tetrapoda, in: Costello, M.J. et al. (Ed.) (2001). European register of marine species: a check-list of the marine species in Europe and a bibliography of guides to their identification. Collection Patrimoines Naturels, 50: pp. 375-376