Purnululu National Park, Australia

| Topics: |

Contents

- 1 Geographical Location

- 2 Dates and History of Establishment

- 3 Area

- 4 Land Tenure

- 5 Altitude

- 6 Physical Features

- 7 Climate

- 8 Vegetation

- 9 Fauna

- 10 Cultural Heritage

- 11 Local Human Population

- 12 Visitors and Visitor Facilities

- 13 Scientific Research and Facilities

- 14 Conservation Value

- 15 Conservation Management

- 16 Further Reading

Geographical Location

Purnululu National Park (17º15’ to 17º46’S and 128º15’ to 128º55’ E) is a World Heritage Site located in the East Kimberley region of the state of Western Australia, in the far north-west of the continent. Situated 450 kilometers (km) directly south south-west of Darwin and approximately 300 km by road, south of the town of Kununurra, the nominated site is bounded by the Ord River to the south and east. Geographical co-ordinates of the park are 17º15’ to 17º46’S and 128º15’ to 128º55’ E.

Dates and History of Establishment

Purnululu National Park, Australia. (Source: Australian Government: Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts)

Purnululu National Park, Australia. (Source: Australian Government: Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts) Purnululu National Park was first created by the National Parks and Nature Conservation Authority of Western Australia (now the Conservation Commission) in 1887. It is a class “A” reserve (number 39897). The original vesting was gazetted on 6 March 1987, it’s status was upgraded to “A” class on 13 September, 1988. Prior to the declaration of the Purnululu National Park, the sand plain and grasslands surrounding the Bungle Bungle Range and along the River Ord formed part of the Ord River Regeneration Reserve, first designated in 1967. Under it’s current National Park designation, the nominated area and the surrounding buffer zone (Purnululu Conservation Reserve), are owned by the Western Australia State Government and managed by the Department of Conservation and Land Management (CALM), under the 1984 Conservation and Land Management Act. This act is currently being amended to allow Purnululu National Park and Purnululu Conservation Reserve to be vested with a Prescribed Body Corporate. If successful this legal entity could then hold native title on behalf of traditional owners (local Aborigine tribes in the area), thus allowing the park to convert to conditional freehold. It is likely that a perpetual or termed lease will be established, for CALM to manage the property on behalf of the Purnululu Park Council, a body made up of the representatives of the traditional owners and CALM.

Area

The area inscribed on the World Heritage List (Purnululu National Park) covers a total area of 239,723 hectares (ha). Purnululu Conservation Reserve is located adjacent to the park and extends over an area of 79,602 ha, it is managed as a buffer zone to better protect Purnululu National Park.

Land Tenure

Government of Western Australia. Administered by the State Department of Conservation and Land Management (CALM), for the Conservation Commission of Western Australia.

Altitude

Ranges from 350 meters (m) to 600 m above sea level in Purnululu National Park (the Bungle Bungle Range). In Purnululu Conservation Reserve (which forms a buffer adjacent to the World Heritage listed area), the altitude rises to a maximum height of 720 m above sea level.

Physical Features

Purnululu National Park comprises four major ecosystems: the Bungle Bungle Mountain Range, a deeply dissected plateau that dominates the center of the Park; wide sand plains surrounding the Bungle Bungles; the Ord River valley to the east and south of the Park; and limestone ridges and ranges to the west and north of the Park.

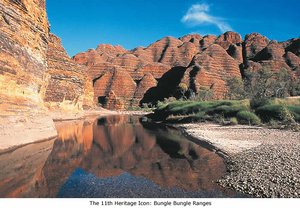

The Bungle Bungle Mountains are an unusual and very dramatic plateau of Devonian quartz sandstone (approximately 360 million years old), created through a complex process of sedimentation, compaction, uplift (caused by the collision of Gondwanaland and Laurasia approximately 300 million years ago and the convergence of the Indo-Australian Plate and the Pacific Plates 20 million years ago), as well as long periods of erosion. The Bungle Bungle landscape comprises a mass of beehive-shaped towers with regularly alternating, dark gray bands of cynobacterial crust (single cell photosynthetic organisms). The plateau is dissected by 100-200 m deep, sheer-sided gorges. The cone-towers are steep-sided, with an abrupt break of slope at the base and have domed summits. Their surface is fragile but stabilized by crusts of iron oxide and bacteria. They provide an outstanding example of land formation by dissolutional weathering of sandstone, with removal of sand grains by wind, rain and sheet wash on slopes.

The Bungle Bungle Range is one of the most extensive examples of sandstone tower karst in the world. (Source: 175th Anniversary of Western Australia)

The Bungle Bungle Range is one of the most extensive examples of sandstone tower karst in the world. (Source: 175th Anniversary of Western Australia) The Bungle Bungle Range is one of the most extensive and impressive occurrences of sandstone tower karst in the world. Comparative areas include the tapuis of the Canaima World Heritage Area in Venezuela, the Wulingyuan Scenic & Historic Interest World Heritage Area of China, the Chimanimanie Highlands on the Zimbabwe-Mozambique border, and the Vila Velha region of Southern Brazil, but all these have a different geomorphological evolution and are within different bioclimatic realms from the Bungle Bungles. Within Australia, there are several examples of tower karst landscapes in quartzites, such as the ruiniform relief of Arnhemland Plateau, the Watarrka and Keep River national parks in the Northern Territories, and Monolith Valley in New South Wales. In all these cases, the tower karst is smaller in scale and different in terms of geological composition and landform evelolution from that in Purnululu National Park.

The grassy Ord River valley on the east and south of the Park drains two creeks from the south (Bellburn Creek and Piccaninny Creek) and three creeks from the north of the mountains (Red Rock Creek, Osmand Creek and Buchanan Creek), deeply incised as a result of crustal uplifting during relatively recent geological times. The wide sand plains between the uplands and the river are composed of infertile black soil covered with grassland and scattered trees. The limestone ridges to the west and Osmand Range to the north are better wooded, especially in the forested Osmand Creek valley. These rocks are believed to be of Cambrian age (550-500 million years old). There are stromatolites in the Osmand range.

Climate

The region has a dry monsoonal climate, characterized by two contrasting seasons. The summer wet season (November-March) is very hot, with an average maximum temperature in October of 38.3 degrees Celsius (ºC), and receives all of the annual rainfall of between 500-700 millimeters (mm), often in heavy falls during thunderstorms. The winter dry season (April - October) has an average minimum July temperature of 29.1ºC and occasional night frosts. Evaporation exceeds 2,000 mm with rapid run-off. There is little dry season stream flow or permanent water except for pools in well-sheltered gorges.

Vegetation

The sandstone grevillea Grevillea miniata is found only in Purnululu National park. (Source: Australian National Botanic Gardens)

The sandstone grevillea Grevillea miniata is found only in Purnululu National park. (Source: Australian National Botanic Gardens) The Park's vegetation reflects its transitional location between the northern tropical savanna and inland arid desert biogeographical regions. Some 17 vegetation communities are recognized according to moisture availability, ranging from closed forests in the gorges and valleys, through open forests in riparian areas and open woodlands of drier areas, to stunted shrublands and grasses in the driest uplands and surrounding plains. The dominant vegetation in the Park is open woodland and spinifex (spiny hummockgrass) grassland, with many eucalypts, acacias and grevilleas; notably silverleaf bloodwood Eucalyptus collina and roughleaf range gum E.aspera, The regionally endemic sandstone grevillea Grevillea miniata, and rock grevillea G.psilantha, are found only in the Park. The transitional location has made the Park a center of endemism for spinifex (Triodia spp.) resulting in the highest density of species anywhere in Australia (13 in a 1º x 1.5º quadrat), including T.bunglensis, which is endemic to the Park. The southernmost penetration of monsoonal savanna species brings palms, orchids and ferns into the microenvironments of the deeper valleys. The transitional climate may also explain the presence of the five species of bacteria, which are very ancient single-cell photosynthesizing organisms, which form a striking gray crust on alternate layers of sandstone over a wide area of the mountains. In all, 653 plant species are recorded from the Purnululu area, including 628 higher plants (of which 597 are native), 17 ferns and fern allies and 8 species of lower plants.

Fauna

The diversity of the animals in the park also reflects the mixing of tropical and desert species. The recorded fauna of the Park comprises 298 vertebrate species: 41 mammals, 149 birds, 81 reptiles, 12 amphibians and 15 fish. It is composed of animals from both desert and savanna ecosystems and includes species such as: skinks Scincidiae, monitor lizard Varanus dumerilii, and shorteared wallaby Petrogale brachyotis. These are all arid land animals found on the mountain plateau top, while in the sheltered valleys below are varieties of frogs, the pale field rat Rattus tunneyi and largefooted mouse-eared bat Myotis adversus which are damp environment species. Birds pass through on migration from the north in the wet season and from the south in the dry season. One rare grassland species is the grey falcon Falco hypoleucas (VU) of which only about 1,000 are said to remain.

Cultural Heritage

Aboriginal Australians have lived in the Ord River region for at least 40,000 years. It was and still vestigially remains a hunter-gatherer culture, with people moving from the desert to the uplands in the wet season, to foothill pools after the rains and along the [[river] ] in the dry season, when this becomes a vital resource and refuge. Fire was historically used to manage the environment, to create a mosaic of vegetation with different uses.

Two main tribal groups and their economic networks, one based on the desert and the other on the savanna, meet in the area, each having two languages. Historically these groups particularly utilized the Ord River Valley, Red Rock and Osmand creeks. Aboriginal religious observance is based on their country, which guides the culture. This "Law", like the 'Dreaming' elsewhere, is called Ngarrangkarni. It envisages the landscape as an embodiment of spiritual and cultural values: as a record of the creation, of past history, of past ancestors, of their laws and ceremonies and traditions of food production and networks of exchange.

This belief enabled the Aborigines in this area to survive the impact of colonization by pastoralists. These started to arrive in the area after 1884, taking up 50,000-300,000 ha leases on the native lands. By 1902 there was nearly 50,000 head of livestock on the Ord River grasslands. Also, in 1885 there was a gold rush at Hall's Creek 100 km to the south, bringing an influx of miners. The Aboriginals suffered from introduced diseases, murder, erosive destruction of waterholes and riverbanks by overgrazing and received only food in payment for work. To stop livestock raiding, the government provided some refuges and food but did not stop the cultural dispossession, which occasioned it and continued into the 1970s.

Local Human Population

By 1967, the area had been used for pastoralism for 80 years. But by this time, erosion caused by overgrazing had begun silting up the new Lake Argyle downstream which led the state government to create the Ord River Regeneration Reserve to control erosion by limiting numbers of stock and carrying out revegetation of the bare land. The state government also decreed that the Aboriginals should be paid for their work. They were however forbidden from living on the local sheep stations and banished to refuges, settling at Turkey Creek to the north and Hall's Creek to the south.

In the 1970s senior Aboriginals petitioned for return to their country and expressed their discontents in public ceremonies and through paintings, made as records of their country and past history, which are now widely appreciated as works of art by collectors. They regard proper maintenance of their land as essential to their cultural survival. After the National Park was mooted, livestock numbers were at last reduced. Living Area leases in the Park for some traditional Aboriginal owners have been signed recently with the Purnululu Aboriginal Council (an incorporation giving legal identity to indigneous communities and eligibility to reveive government funds). The park authorities intend to establish more of these leases in the Park.

Visitors and Visitor Facilities

The Park has only been widely known since media promotion in 1983 of the Bungle Bungle Mountains. In 1986 there were 2,350 visitors by land. By 1996 there were 14,500 visitors by land and some 40,000 by aerial tour. There are now about 18,000 ground-based visitors a year. Development of visitor facilities is mostly concentrated on the west side of the park. There is a visitors center, airstrip and helipad, two commercial and two public campsites, 50 km of internal vehicle tracks and 7 walking trails ranging from 30 minutes long to a 30 km overnight trip. There is no access to the Park during the wet season (November to March) except from the air to the commercially run camp, because of seasonal flooding along the access track. This is kept suitable for 4-wheel-drive cars only, in order to control tourist numbers and encourage them to take aerial or guided safaris. There are calls to improve access, which will require increased infrastructure, facilities and staff. Meeting the growing interest in indigenous cultures should increase the economic benefits to local people from direct employment, crafts and their art.

Scientific Research and Facilities

The first geological map of the area was made in 1884. In the 1930s three studies of Aboriginal occupations and social organization were made. In the 1980s there was a botanical survey of the mountains and Osmand Range, investigation of the geomorphology and structure of the sandstone and in 1988 a three month survey of archaeological sites on the north and west margins. In 1992, Woinarski and others surveyed the vegetation and wildlife of the Park and surroundings. In 1997, Hoatson and others from the Australian Geological Survey Organisation brought together all the existing data on the area and in 2001, Kirkby & Williams described the cultural values of the native inhabitants.

Conservation Value

The Bungle Bungle Range in the Park is a spectacular and extensive karst landscape of sandstone towers of sandstone banded with grey cyanobacteria. Its surrounding plains and riverine areas occupy a biogeographical region midway between desert and savanna, with wildlife and flora from both and several endemic species. Within it lives one of the few surviving 40,000-year-old hunter-gatherer societies, which has retained its vitality despite more than a hundred years of hostile colonization. The relationship of these people to the land, comprehensively expressed in the Law or Ngarrangkarni, is also revelaed in the now famous paintings of the Aboriginal Turkey Creek artists.

Conservation Management

The uplands are in good condition, but erosion of the sand plains following intensive and continuous overgrazing has caused destructive silting downstream. In response to this the Ord River Regeneration Reserve was established to limit stock numbers and revegetate bare land. In 1985-1986 the proposed designation of the National Park led to the removal of 25,000 cattle, 4,000 donkeys and some camels. Programs were also instituted for feral cat control, and protective burning as practiced by traditional owners, to create vegetation mosaics and decrease the destructiveness of wildfires to which the now recovered grasslands are vulnerable.

The National Park is managed under the Conservation & Land Management Act of 1984. The Department of Conservation and Land Management is now arranging the Park's future joint management with the "traditional owners" under the Purnululu Park Council. These owners who are Aboriginal claimants registered under the Commonwealth Native Title Act of 1993, were previously not allowed to live in the Park. However, their knowledge of the ecology and how to manage the land can be drawn on. For them, this is managing their own cultural survival as well as providing employment, training and funding. They are being given the opportunity to return and live seasonally in Living Area leases inside the Park. If it is accorded World Heritage status, the Park will be protected under the Commonwealth Environmental Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act of 1999, and key indicators and monitoring of the state of conservation will be developed by the Park's Council and Advisory Committee when these bodies have been established.

A management plan (Purnululu National Park Management Plan for 1995-2005) for the Park was compiled in 1995. Currently under mid-term review by the Conservation Commission, it aims to:

- Conserve and protect landforms, ecosystems and areas of scientific and cultural importance;

- Permit Aboriginal traditional owners to live on the land following their customary lifestyle;

- Provide for public recreation;

- Promote appreciation of natural processes and interpretation of the native culture;

- Protect the safety of residents, neighbors and residents;

- Institute research and monitoring of all aspects of the Park to improve its management; and

- Control any commercial and industrial impacts.

Management Constraints

The past pressures of accelerated soil erosion due to overgrazing and the destruction of native animals by exotic wildlife (especially cats) have come under control but continue to need monitoring. Other pressures on the site are not yet serious, however growing visitor numbers will increase the present high level of wear on certain tracks and trails, the erosion of fragile sandstones, and the need for safe vehicle tracks, a fire protection management program, and risk-management from floods and rockfalls. Adequate management of these threats will need considerable further funding.

Staff

The present staff employed at the Park include one Ranger in Charge, one assistant ranger, one (seasonal) visitor center manager and volunteer campground hosts. At least two additional rangers, two maintenance workers and two Aboriginal heritage officers are planned with the granting of World Heritage status. The Department of Conservation and Land Management (CALM) can draw on regional and state expertise, and the Aboriginals can draw on their traditional knowledge of ways to manage the land.

Budget

In 2000-2001, annual funding for the management of the park amounted to AUS $324,620. This originated from the regional management of CALM, and revenue from park entrance fees. To upgrade the Park as a World Heritage site will need facilities, staff and living areas for the traditional owners at a cost estimated at AUD $3.3 million per year for three years plus an average of AUD$400,000 annual operational costs.

Further Reading

- Anon. 1987. Sandstone landforms of the tropical East Kimberley region, Northwestern Australia. J. Geology 95:205-18.

- Anon. 1988. Quartz etching and sandstone karst: examples from the east Kinberleys, Northwestern Australia. Z. Geomorphologie N.F. 32(4): 409-23.

- Environment Australia, (2002). Nomination of Purnululu National Park by the Government of Australia for Inscription on the World Heritage List. 67pp. (Includes a list of 41 references).

- Hoatson, D. et al. (1997). Bungle Bungle Range - Purnululu National Park, East Kimberley, Western Australia: a Guide to the Rocks, Landforms, Plants, Animals and Human Impact. Australian Government Publishing Service, Canberra.

- Kirkby, I. & Williams, N. (2001). Purnululu National Park World Heritage Cultural Values Draft Final Text. Prepared for Environment Australia.

- Western Australian Department of Conservation & Land Management (1995). Purnululu National Park Management Plan, 1995-2005, for the National Parks and Nature Conservation Authority, Canberra.

- Woinarski, J. et al. (1992). A Survey of the Wildlife and Vegetation of Purnululu (Bungle Bungle) National Park and Adjacent Area. Research Bulletin No.6, Department of Conservation & Land Management, WA. ISBN: 073095224X.

- Wray, R.A.L. 1997. A global review of solutional weathering forms on quartzite sandstones. Earth Science Reviews 42:137-160.

- Young, R.W. 1986. Tower karst in sandstone: Bungle Bungle massif, Northwestern Australia. Z. Geomorphologie N.F. 30(2):189-202.

- Purnululu National Park Website

| Disclaimer: This article is taken wholly from, or contains information that was originally published by, the United Nations Environment Programme-World Conservation Monitoring Centre (UNEP-WCMC). Topic editors and authors for the Encyclopedia of Earth may have edited its content or added new information. The use of information from the United Nations Environment Programme-World Conservation Monitoring Centre (UNEP-WCMC) should not be construed as support for or endorsement by that organization for any new information added by EoE personnel, or for any editing of the original content. |