Okavango River

The Okavango River drains a closed basin in southern Africa, with most of the flow dissipating in the Okavango Alluvial Fan within the nation of Botswana. The Okavango course prehistorically included an outflow to the ocean; however, geologic events of uplift and rifting over the prior million years have converted the Okavango Basin to an endorheic system. The Okavango River not only supports a large assemblage of fish and other aquatic biota, but its drainage area embraces habitat for a large variety of mammals, birds and other terrestrial organisms.

The southern Okavango Basin manifests rich archaeological arrays of Early Stone Age tools that demonstrate this area was an important locus for early man and even earlier tool-making hominid species; this Eartly Stone Age culture thrived in the region in an era of a much wetter climate, when the Makgadikgadi Pan was a vast permanent lake along the Okavango River.

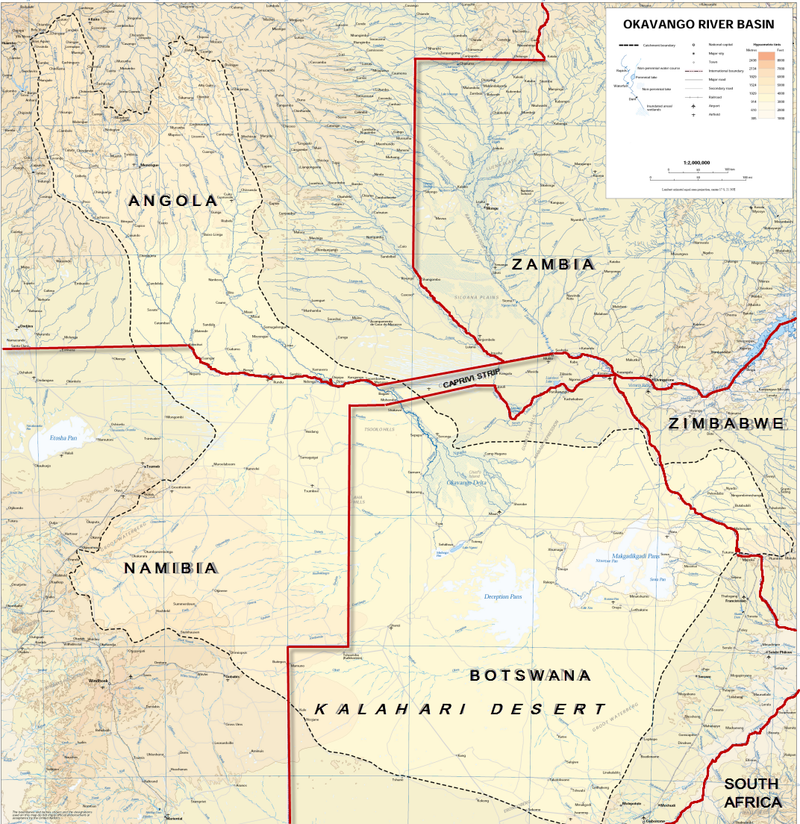

Okavango River Basin map. Source: United Nations

Okavango River Basin map. Source: United Nations

Contents

Geologic history

The Makgadikgadi Pan is a large depression (the Kalahari Basin) that once held a lake that spanned most of northern Botswana. The Zambezi, Okavango and Kwando/Chobe Rivers fed this ancient Lake. The formation of various faults on the southern extremity of the East African Rift Valley diverted the flow of these rivers away from the lake, causing it to slowly dry up. This drying process concentrated salts in the lake bed, eventually leaving flat, salt-saturated clay pans (the Makgadikgadi Pans complex). The lake was its deepest in the area of the Ntwetwe and Sua Pans, which were the last areas to dry up, and are today the most saline. Steep escarpments of white calcrete, marking the perimeter of the ancient lake, run along the shores of the pans, rising between 70 and 100 meters (m) above their surface. The only body of water to remain from the once massive lake is the Okavango Alluvial Fan in the northeast of Botswana.

Hydrology

Although prehistorically the Okavango had a discharge that eventually led to the sea, in modern times the basin is endorheic, with most of the river flow terminating in the porous soils of the Okavango Alluvial Fan (usually but incorrectly termed the Okavango Delta). Rising in Angola, the Okavango has a total length of approximately 1600 kilometres.

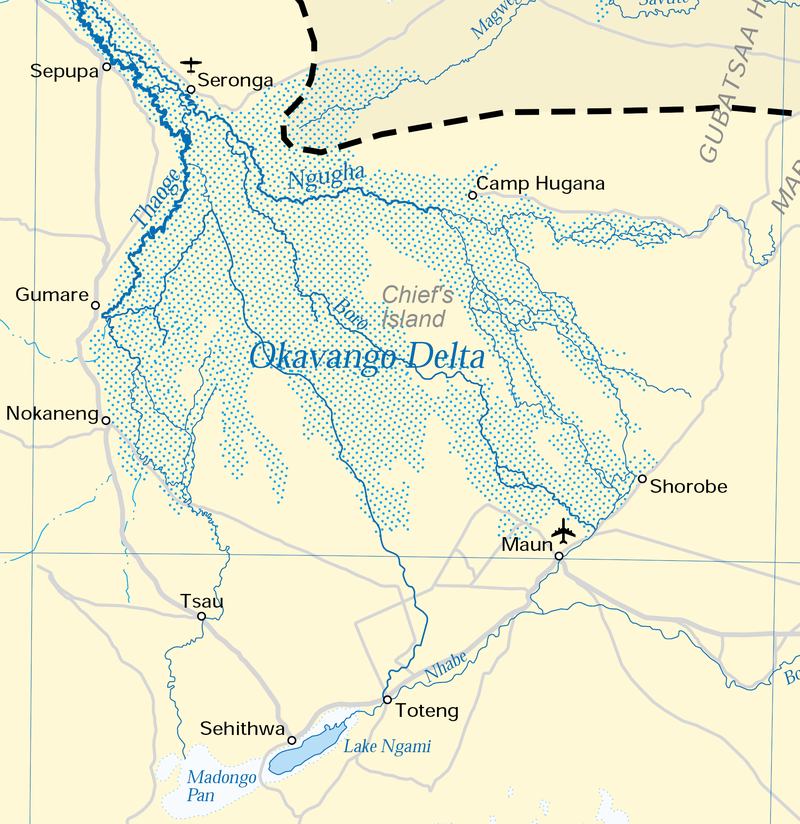

Okavango Alluvial Fan (Delta). Source: United Nations

Okavango Alluvial Fan (Delta). Source: United Nations

Aquatic biota

One of the endemic species in the Okavango River is the 30 centimetre (cm) long demersal broadhead catfish (Clariallabes platyprosopos). Another example native demersal fish species occurring in the Okavango is the 32 cm smoothhead catfish (Clarias liocephalus).

Native benthopelagic species occurring in the Okavango River include the ten cm Okavango tilapia (Tilapia ruweti), the nine cm hyphen barb (Barbus bifrenatus) and the six cm spottail barb (Barbus afrovernayi).

Native pelagic fish species found in the Okavango River include the 95 cm elongate tigerfish (Hydrocynus forskahlii), the 11 cm sharptooth tetra (Micralestes acutidens) and the nine cm Okavango robber (Rhabdalestes maunensis).

Terrestrial ecoregions

Terrestrial ecoregions within the Okavango Basin. Source: WWF The chief ecoregions within the Okavango Basin are:

Terrestrial ecoregions within the Okavango Basin. Source: WWF The chief ecoregions within the Okavango Basin are:

- Zambezian baikiaea woodlands

- Zambezian flooded grasslands

- Zambezian and mopane woodlands

- Kalahari acacia baikiaea woodlands ecoregion

- Zambezian halophytics

The Zambezian baikiaea woodlands cover much of the northern Okavango basin along the Angola/Botswana border area. Baikiaea plurijuga is the sole dominant, forming a fairly dense, dry, semi-deciduous forest with trees up to 20 metres in height. There is a dense and shrubby understory of Combretum engleri, Pteleopsis anisoptera, Pterocarpus antunesii, Guibourtea coleosperma, Dialium engleranum, Strychnos spp., Parinari curatellifolia, Ochna pulchra, Baphia massaiensis subsp. obovata, Diplorhynchus condylocarpon, Terminalia brachystemma, Burkea africana, Copaifera baumiana and Bauhinia petersiana serpae. Lianas and climbers are also common in the understory, including Combretum elaeagnoides, C. celastroides, Dalbergia martinii, Acacia ataxacantha, Friesodielsia obovata, and Strophanthus kombe. Smaller shrubs are scattered beneath the thicket. The herb layer is conspicuous solely during the rainy season. Grasses vary from sparse to dense and include Leptochloa uniflora, Oplismenus hirtellus, Panicum heterostachyum, and Setaria homonyma. Other conspicuous herbs are Aneilema johnstonii and Kaempferia rosa.

In the area west of the Okavango Alluvial Fan and in the area occupying southeast Namibia, the tree savanna becomes dominated by Baikiaea plurijuga, with varying proportions of Colophospermum mopane and Burkea africana. With fire protection, a dense shrub layer develops and Baphia massaiensis, Bauhinia petersiana, and Paropsia brazzeana are all common. The grass layer is sparse when the shrubby understory is well developed, but when it is more open, species such as Aristida meridionalis, A. congesta, Eragrostis pallens, and E. lehmanniana are found. Baikiaea plurijuga (Caesalpinaceae) is fire sensitive and when fire damage is severe, this cover can vanish completely.

Meerkat eating scorpion, Makgadikgadi. @ C.Michael Hogan Most of the flow of the Okavango River dissipates within the Okavango Alluvial Fan, in an ecoregion known as the Zambezian flooded grasslands. this ecoregion falls within the center of distribution of the globally threatened slaty egret (Egretta vinaceigula, VU). Largely restricted to this ecoregion, this species is an uncommon resident of the marshes and floodplains of the Okavango, Chobe/Kwando, and the Caprivi Strip as well as from the [[Zambezi] River] Valley northwards to the Bangweulu swamps.

Meerkat eating scorpion, Makgadikgadi. @ C.Michael Hogan Most of the flow of the Okavango River dissipates within the Okavango Alluvial Fan, in an ecoregion known as the Zambezian flooded grasslands. this ecoregion falls within the center of distribution of the globally threatened slaty egret (Egretta vinaceigula, VU). Largely restricted to this ecoregion, this species is an uncommon resident of the marshes and floodplains of the Okavango, Chobe/Kwando, and the Caprivi Strip as well as from the [[Zambezi] River] Valley northwards to the Bangweulu swamps.

At the southern edge of the Okavango Alluvial Fan and with a narrow finger extending north across the Namibian border is the Zambezian and mopane woodlands. The mopane tree characterizes the entire ecoregion, and in many places dominates to the exclusion of other species, particularly trees. Mopane trees are ecologically valuable as browse for numerous animals, notably elephants, and economically the wood is prized for building material and fuel. In addition, this tree is the major host for the seasonally abundant mopane worm (Gonimbrasia belina), the larval stage of a moth which is characteristic of the mopane woodlands. The mopane worm is an important human food and economic resource. Other important taxa in the ecoregion are the families Combretaceae and Mimosaceae, which are represented by 34 and 56 tree and shrub species respectively.

The Kalahari acacia baikiaea woodlands ecoregion covers much of the southern portion of the Okavango Basin. Deciduous tree and bush savanna covers most of the ecoregion, in the sandveld area. Taller trees are mainly confined to low sand ridges and are dominated by Terminalia sericea, Burkea africana, Peltophorum africanum, Croton gratissimus, Rhus tenuinervis, Acacia giraffe, A. fleckii, A. luederitzii, Combretum zeyheri, C. apiculatum, and Ziziphus mucronata. A shrub savanna occurs on the gently rolling plains between the sand ridges and is mainly composed of Dichrostachys cinerea, Grewia flava, G. flavescens, Acacia mellifera, Bauhinia macrantha, Ximenia caffra, and Commiphora pyracanthoides. The grass cover includes Stipagrostis uniplumis, Aristida meridionalis, A. congesta, Eragrostis pallens, E. superba, Heteropogon contortus, Cymbopogon excavatus, and Digitaria eriantha.

The Zambezian halophytics stretch out within the southern portion of the Okavango Basin. This seasonal lake represents an overflow area of the Okavango, which bears surface water as a large shallow lake, the Makgadikgadi Pan, when the Okavango overflows its usual sump in the Okavango Alluvial Fan. On the saline fringes two macrophytes predominate; Sporobolus spicatus and the spiny grass Odyssea paucinervis. Salt marshes are found scattered around the wetter fringes of the pans. These marshes support species such as Portulaca oleracea, Sporobolus tenellus, and Saudea fruticosa. Surrounding the pans on a larger scale (on less brackish soil) are grasslands dominated by Odyssea paucinervis and Cynodon dactylon with Cenchrus ciliaris and Eriochloa meyeriana dominating the crests of calcrete escarpments. These grasslands have few trees, except to the west where Hyphaene palms fringe the drainage lines, extending north to Nxai Pan. The fruit of these palms is known as vegetable ivory and is used by the local people to make necklaces and heads for walking sticks. To the north and northwest of Ntwetwe Pan individual baobab (Adansonia digitata), Acacia kirkii, and Acacia nigrescens trees are found scattered throughout the grassland

Prehistory

Early Stone Age tools, Makgadikgadi, courtesy of Jacks Camp Museum @ C.Michael Hogan Significant recovery of Early Stone Age tools has derived from the southern part of the watershed in the [[Makgadikgadi Pan]s], as vestiges of habitation by Homo sapiens and even Homo habilis. Much of the extant collection is exhibited at Jack's Camp Museum located in the north end of the pans. Field reconnaissance in the dry lakebeds yielded extensive surficial specimens of early stone tools and later projectile points.

Early Stone Age tools, Makgadikgadi, courtesy of Jacks Camp Museum @ C.Michael Hogan Significant recovery of Early Stone Age tools has derived from the southern part of the watershed in the [[Makgadikgadi Pan]s], as vestiges of habitation by Homo sapiens and even Homo habilis. Much of the extant collection is exhibited at Jack's Camp Museum located in the north end of the pans. Field reconnaissance in the dry lakebeds yielded extensive surficial specimens of early stone tools and later projectile points.

Late Stone Age man would have lived in the southern Okavango Basin in huts made of sticks and grass in nomadic groups of 15 to 60 individuals .The women would have concentrated on gathering fruits and nuts, while men created snares of twine to catch springhares emerging from their burrows. Springbok and eland were hunted by spear and arrow, as the Later Stone Age tools had become quite sophisticated. Although no rock paintings are found in the pans, somewhat north in the Tsodilo Hills there is a wealth of animal and human subject rock art, some dating as early as 24,000 years before present.

References

- Fishbase. 2010. Species in Okavango

- A.Gieske. 1996. Modelling of the surface overflow of the Okavango delta, Botswana Notes and Records, vol. 28, pp 165-192C. Michael Hogan. 2008. Makgadikgadi, The Megalithic Portal, ed. A.burnham

- B.J.Huntley. 1978. Ecosystem conservation in southern Africa. M.J.A. Werger, editor. Biogeography and Ecology of Southern Africa. W. Junk, The Hague. ISBN: 9061930839

- Graham McCulloch. 2003. The ecology of Sua Pan and its flamingo populations, PhD thesis, University of Dublin, Ireland

- S.N.Stuart, R.J. Adams and M.D. Jenkins. 1990. Biodiversity in sub-Saharan Africa and its Islands. Chapter 8: Botswana. Occasional Papers of the IUCN Species Survival Commission No. 6. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland. ISBN: 2831700213

- Thomas Tlou and Alec Campbell. 1984. History of Botswana. MacMillan ISBN 99912-74-08-7

- M.J.A.Werger. 1978. Biogeography and Ecology of Southern Africa. Monographie Biologicae vol. 31., The Hague. ISBN: 9061930839

- World Wildlife Fund. 2002. Zambezian flooded grasslands ecoregion