Improving understanding through environment and policy interlinkages in Africa

Contents

- 1 Introduction Box 1: Environmental change impacts lake population in Ethipian Highlands (Source: RCMRD (Improving understanding through environment and policy interlinkages in Africa) 2005)

- 2 Demographic and environmental change

- 3 Innovation and environmental change

- 4 Economic and environmental change

- 5 Trade and industry

- 6 Investment, aid and debt

- 7 Further reading

Introduction Box 1: Environmental change impacts lake population in Ethipian Highlands (Source: RCMRD (Improving understanding through environment and policy interlinkages in Africa) 2005)

A myriad of social and economic factors, ranging from demographic changes, poverty and health, industry and trade, economic liberalization including structural adjustment programmes (SAPs) and resource extraction impact on and shape the environmental challenges facing Africa. Thus understanding problems and defining effective responses to the challenges presented often requires multilevel and inter-sectoral cooperation.

Directly and indirectly, anthropogenic activities affect ecosystem health and productivity. Economic factors, particularly trade, and science and technology, are major recurring themes that affect, and in many cases exacerbate, problems.

A key challenge facing Africa is the entrenched nature of poverty, which traps people into unsustainable livelihoods and perpetuates their dependency on the primary use of natural resources. This subsistence-based existence is further compromised by extreme weather events, such as droughts, and cumulative environmental change. Box 1 highlights the interlinkages between environment and human society and looks at how environmental change and in particular the disappearance of the Alemaya lakes in the Ethiopian Highlands has changed the lives of more than half a million people of that area.

Demographic and environmental change

Demographic change impacts on the environment in many ways. The relationship between demographic factors and the environment is multidimensional and is affected by change in other sectors including trade, economic activity, investment, research and the development of technology. Poverty, health and governance systems are also closely linked to how demographic changes will impact on the environment.

Population growth and density is one of the most important drivers of environmental change in Africa, particularly as this relates to the exploitation and use of the environment as well as to waste generation and its management. In the last two decades (1980-2000), the population of Africa grew from 469 million to 798 million, increasing demand for food, water, arable land and firewood as well as other material needs such as education, health care, housing, energy, transport and infrastructure. Related activities in, but not limited to, industry and trade create new environmental pressures and thus, if poorly managed, economic growth can negatively impact on the environment.

Expanded economic activities which are poorly planned and inadequately monitored can place increased pressure on ecosystems, including forests and woodlands, and coastal and marine areas, through the loss of biodiversity, habitat degradation, and water (Water pollution), land and air pollution. However, the pressure placed on the environment by a growing population is exacerbated by the lack of alternative livelihoods. Limited opportunity for adding value to natural resources harvested and an economy that encourages the export of unprocessed materials may lead to ever-increasing harvests. Increased use of natural resources, for example the use of biomass in many cities in Western Africa for charcoal production to meet growing energy needs, is a result of the lack of alternative clean and environmentally friendly energies, which in turn can be attributed to the lack of investment in research and development.

The degradation of natural resources may adversely affect the very livelihoods dependent on them, forcing people to develop coping strategies that can be detrimental to ecological sustainability. The Africa’s urbanized population is expected to reach 53.5 percent, compared to 39 percent today (compiled from WRI 2005). Africa is the fastest urbanizing region in the world and it is also one of the poorest. Although urbanization is closely associated with people seeking new livelihood opportunities, rapidly growing urban environments may not be able to provide these. Urbanization may create new pressures on existing infrastructure, leading to the spread of informal settlements. Some 72 percent of Africans living in urban areas live in slums without access to basic environmental or social services. Urban livelihoods in Africa are often characterized by worsening standards of human well-being including:

- Inadequate access to shelter and security of tenure, and all the problems associated with overcrowding;

- Growing vulnerability to environmental health problems and natural disasters;

- Growing inequality and increasing crime and violence, which have a disproportionate impact on women and the poorest of the poor; and

- A lack of community participation in decision making.

The extreme deprivation of health, education and other services as well as poor social relations makes breaking out of poverty difficult. These factors, along with the lack of opportunity available to poor people, have heavy environmental costs.

Box 2: Environmental and social impacts of urban agriculture

Box 2: Environmental and social impacts of urban agriculture(Source: IDRC 2002)

In the absence of viable alternative livelihoods, urbanization may, in itself, constitute an increased pressure on natural resources through direct and indirect use. Inadequate urban planning, including poor infrastructural development, and the inability of the economic sector to fully absorb growing needs, means that urban populations continue to rely on natural resources as a source of supplementary income. This may include collecting natural resources, such as wild fruit and firewood, for immediate domestic use or as the basis for commercial activity. Urban agriculture is a particularly important phenomenon. In Northern Africa, urbanization is leading to the loss of fertile land, desertification, soil erosion, clearance of forests and woodlands, and pollution of surface and groundwater. In Southern Africa, as shown in Box 2, SAPs resulted in more poor people in urban areas engaging in agriculture.

There can be remarkable damage to marine and coastal ecosystems from urban expansion and sprawl in coastal zones, as shown in Coastal and Marine Environments in Africa. Coastal and marine pollution, and the resulting degradation of water quality, are driven by urban, residential and industrial wastes from inland systems as well as from coastal cities. Growing urban areas attract major industrial clustering. In many countries, industrial and mining activities contribute significantly to water and atmospheric pollution, placing new burdens not only on the environment and human health but also on already struggling public sector institutions, such as health services and local government institutions, which are often responsible for regulating and managing pollution management. In Eastern Africa, the clearance of mangroves for urban settlements is affecting marine and coastal ecosystems.

These environmental problems are not simply the result of population growth, but are closely linked to other social and economic factors. For example, the lack of adequate investment in infrastructural development that can support these growing communities is an important factor contributing to the lack of economic opportunity, high environmental costs and thus low levels of human well-being. High transportation costs in Africa have a severe impact on trade, increasing the costs of products and suppressing demand. The railways and roads put in place in colonial times were primarily designed to transport minerals and other raw materials to the ports for shipping to Europe. They were not designed to encourage trade among African sub-regions. Africa’s transport costs – local, national, regional and international – are twice or more than those of Asian countries.

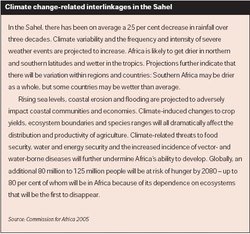

The short-term positive human well-being gains and the negative environmental costs demonstrate the need for policy approaches that can create a win-win situation. The capacity for resilience is further undermined by a variety of socioeconomic factors including poverty and the lack of public access to information and knowledge in vulnerable areas. The high level of vulnerability to environmental changes has consequences at multiple levels – and many African countries’ economies are particularly susceptible, as shown in Boxes 3 and 4.

Innovation and environmental change

Innovation drives human society, but brings with it both benefits and costs. Science and technology can be a double-edged sword, sometimes pushing forward economic opportunities through new applications and products, and sometimes causing adverse environment effects, such as pollution. However, improved knowledge, especially in the context of a strong sciencepolicy link, based on African priorities and inclusive of public, private and civil actors, can lead to important initiatives that support sustainable development by addressing key challenges.

Many policy initiatives, including the World Summit on Sustainable Development (WSSD) Johannesburg Plan of Implementation and New Partnership for Africa's Development (NEPAD), address this urgent need for investment in science and technology. Nevertheless, it is important not to see science and technological development as a silver bullet. Chapters 9 and 11 look at the challenges and opportunities of science in relation to genetically modified crops and chemicals, respectively.

One of the many benefits of science has been the improvement in society’s ability to respond more effectively to environmental change and shocks. However, the opportunities available to Africa remain constrained due to low levels of technological and overall development and this has far-reaching adverse consequences for both ecosystems and human wellbeing. Disaster preparedness and response are closely linked to levels of investment in science and technology, and to governance systems. In much of Africa, the capacity for resilience is further undermined by a variety of socioeconomic factors including poverty and the lack of public access to information and knowledge in vulnerable areas. The high level of vulnerability to environmental changes has consequences at multiple levels – and many African countries’ economies are particularly susceptible, as shown in Boxes 3 and 4.

These Boxes demonstrate the importance of an interlinkages approach in both problem analysis and in finding solutions: scientific and technology interventions that take into account the social and economic realities should be prioritized over the importation of technologies developed elsewhere, and closely linked to economic, environment and development strategies. Investment in education as well as in public institutions is essential. Responding appropriately to the challenge of climate change, declining rainfall and desertification is one area where the need for increased understanding is necessary for developing appropriate early warning and mitigation strategies. The web of intertwined negative impacts of climate change is depicted in Box 3. The multiple impacts, across sectors and at different levels, indicate the need for an interlinkages approach to both research and response.

Economic and environmental change

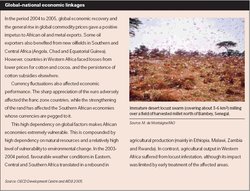

Economic activities straddle national boundaries and are affected by global, regional and national processes. Global policies and practices have direct impacts, at national and regional levels, on environmental sustainability and human well-being – sometimes increasing opportunities, but at times decreasing opportunities. An interlinkages approach can be effective in maximizing opportunities and minimizing negative impacts. Such an approach can offer opportunities for a better understanding of the globalregional- national links and set the basis for more effective institutional and policy responses.

Africa has made dramatic economic improvements since 2002 – in addition to impressive growth rates, inflation is also at an all-time low. In 2004, Africa achieved a growth rate of 5.1 percent, the highest in the last five years and significantly higher than the rates of 3.7 percent in 2003 and 2.9 percent in 2002. However, the challenges facing Africa remain immense. Despite the richness of its biological, mineral and human resources, the region remains poor and levels of human well-being are in decline for many countries. The 2005 Human Development Index (HDI) shows that more than 20 countries in sub-Saharan African (SSA) have suffered dramatic reversals in human development since 1990. Sub-Saharan Africa must grow an average 7 percent per year to reduce poverty by half by 2015. Food insecurity threatens millions each year, especially in the Horn of Africa and Southern Africa. Africa is home to more malnourished people than any other continent and hosts 27 percent of those who lack access to safe water at the global level.

Africa and its people face many obstacles in turning their natural assets into wealth. These have their roots in policies and practices at the global level: the arenas of international trade, development aid, and international finance and investment influence the broad economic and political setting that Africa finds itself in, places it at a distinct disadvantage and perpetuates poverty. Africa’s economic, political, social and cultural systems are increasingly susceptible to globally-driven policies due to globalization. Box 4 shows how closely linked national economic performance is to the global economy as well as to environmental change. The challenge for Africa lies not only in how to make economic activity more efficient, in terms of production and environmental costs, but also in how to deal with the ramifications of global imbalance and its impacts on sustainable development and human well-being. The opportunities offered by globalization need to be harnessed while, at the same time, Africa must take measures to protect and cushion itself from potential negative effects.

Trade and industry

Trade is incredibly powerful, with taxes, tariffs, import quotas and subsidies imposed elsewhere affecting opportunities for human well-being and sustainable environmental management in the developing world, including in Africa.

The global market and the policies of multilateral economic organizations have implications for the Africa region. The balance of power in international trade organizations, such as the World Trade Organization (WTO), is tilted in favour of rich countries despite each country having an equal vote. Trade and trade-related agreements, such as those on intellectual property, may affect the trade opportunities for African countries. Trade liberalization may make it more difficult for countries to pursue their environmental policies where these affect free market opportunities and may demand wide-scale reforms, with uncertain benefits that developing countries can ill afford. Negotiations in multilateral fora may favour those with better access to financial and human resources.

As the Commission for Africa (2005) noted, protectionist policies in some countries have adversely affected fisheries and trade in cotton and sugar in Africa. For example, despite the impressive efforts to reform the cotton sector in Benin, Burkina Faso, Chad and Mali, the persistence of cotton subsidies elsewhere has depressed world prices and damaged their cotton industry.

Subsidies are not the only barriers that Africa faces in international trade. There are also non-tariff barriers and standards which may be difficult for many African nations to comply with. The composition of Africa’s exports has essentially remained unchanged and its share of world trade has collapsed from about 6 percent in the 1980s to 2 percent in 2002. Had its share increased by 1 percent, Africa’s share in the world market would have earned it US$70,000 million, about five times what the region received in development aid.

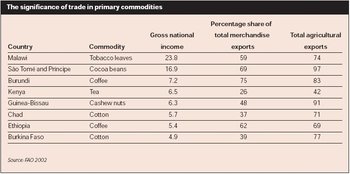

The trade situation of African countries is further worsened by the dependence on a very narrow range of primary commodities (coffee, cocoa, tea, palm oil and minerals). In SSA, for example, those commodities account for about half of merchandise exports. Table 1 shows this trend for selected African countries. The consequences of this dependency are four adverse trends that militate against increasing the countries’ share in international trade:

- Slow market growth;

- Adverse price trends;

- Low value-added; and

- Market competition.

Liberalized trade measures have led to loss of global market share and substantial income in many African countries. The share of food and agriculture in total merchandise trade fell from 17 percent to 10 percent from 1980 to 1997; the terms of trade for Africa’s commodity exports were 20 percent lower at the end of the 1990s than in the early 1970s. Without this, Africa’s share of the world export markets would have been twice as large as it is today. Many agricultural markets are dominated by rich countries, which subsidize their own farmers at US$1,000 million a day or US$365,000 million annually. Trade protectionism by the rich industrialized regimes is the antithesis of free and liberalized trade, policies that have been recommended to developing countries.

Currently, manufacturing, trade, transportation, urbanization, and other activities in the industrialized regions put considerable pressures on the biosphere and stratosphere which influence the environment in Africa and other parts of the world. The G8 countries account for 45 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions, which is a major cause of climate change, global warming and extreme weather events. These changes trigger a series of inter-related biophysical and socioeconomic circles such as drought, floods, hunger, displacement of people and loss of livelihoods, as shown in Box 4. These impacts are particularly severe in Africa given the dependency on natural resources for both subsistence livelihoods, and industry and manufacturing, With more than seven out of ten people engaged in resource-dependent activities, such as subsistence farming, livestock production, fishing, hunting, artisanal hunting and logging, biophysical environment change, whether sudden or cumulative, impacts negatively on the majority of the people.

To respond affectively to these challenges, Africa needs to improve its global competitiveness. As discussed in The Human Dimension, technological and infrastructural investment, developing niche markets, and improving economic and political governance through reducing corruption and conflict are all important strategies to respond to the environmental challenges and to enhance opportunities.

Investment, aid and debt

Global financial relationships have significant implications for economic, development and environmental policies. The continued imbalance makes African countries extremely vulnerable to external pressures. Various African initiatives, including NEPAD, seek to develop interlinkages between the global, regional and national levels – and to engage the global community and to promote more equitable relationships based on partnership and joint responsibility.

Africa’s debt burden continues to be a major drain on economic growth and human well-being. Sub-Saharan Africa’s external debt burden in 2003 amounted to US$185,000 million. The average African country spends three times more on repaying debt than it does on providing basic services to its people. By the end of 2004, Africa will spend about 70 percent of its export earnings on external debt servicing. Additionally, this debt burden has opened Africa up to externally driven economic and political reforms. Although, with globalization and the end of the Cold War, these ties have become less obvious, much development aid remains tied and thus aid remains a crucial driver of development patterns. Poverty Reduction Strategy Papers, for example, serve as a basis for countries to qualify for debt relief and donor assistance under the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) Initiative, concessional lending, and the World Bank’s Country Assistance Strategy.

The debt burden increased from the late 1970s until the late 1990s, as many countries sought loans to service their debts to avoid bankruptcy. The debt burden forced many African countries to liberalize their economies and adopt SAPs: this had far-reaching implications for human well-being and environmental sustainability. Standard features of the SAPs included reducing or removing subsidies on basic commodities and services, and austerity measures in government spending. They also focused on export and macroeconomic stability, reduced the size of the public sector’s share in the economy, liberalized trade and froze government hiring. In most cases, these policies had detrimental environmental and social impacts, as shown in Box 9. Additionally, SAPs resulted in job cuts, forcing the unemployed to clear new land for agriculture, and increased dependence on natural resources. For example, many urban poor people increased agriculture in order to supplement their incomes as discussed in Box 2. Africa’s growing debt burdens, and its repayment obligations, constrain the range of opportunities available to it by locking Africa into unsustainable production systems. Africa’s debt burden is growing despite debt relief to HIPC. Recognizing the linkage between debt and the lack of development, two of the targets for Millennium Development Goals (MDG) 8 specifically commit the global community to address the debt problem.

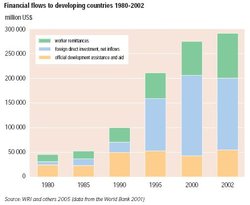

Private capital is playing an increasingly important role in shaping economic development in Africa. Foreign direct investment (FDI) has become the dominant route for financial flows to developing countries as shown in Figure 1. By the mid 1990s, FDI had replaced development aid as the main form of financial inflows to Africa. Although Africa has benefited from increased FDI, its share has remained relatively small and concentrated in extractive industries. Sub-Saharan Africa’s share amounts to about US$62,000 million. Capital inflows from workers’ remittances are significant investment and now exceed official development assistance. In 2000, Africa accounted for about 15 percent of total global remittances of US$72,000 million – that is US$10,700 million. In the same year, Africa also received US$14,413.6 million in official development assistance (ODA) and aid.

Further reading

- AfDB, 2004. Africa Development Report 2004: Africa in the Global Trading System. African Development Bank / Oxford University Press, Oxford

- Bojö, J. and Reddy, R.C., 2002. Poverty Reduction Strategies and Environment: A review of 40 Interim and Full Poverty Reduction Strategy Papers (PRSPs). Environment Department Papers, Environmental Economics Series, Paper No. 86. The World Bank, Washington, D.C.

- Commission for Africa, 2005. Our Common Interest: Report of the Commission for Africa. Commission for Africa, London.

- FAO, 2003. Y4526B/y4526b00.pdf Forestry Outlook Study for Africa – African Forests: A View to 2020. African Development Bank, European Commission and the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome.

- Katerere, Y. and Mohamed-Katerere, J.C., 2005. From Poverty to Prosperity: Harnessing the Wealth of Africa’s Forests. In Forests in the Global Balance – Changing Paradigms (eds. Mery, G.,Alfaro, R., Kanninen, M. and Lobovikov, M.), pp 185-208. IUFRO World Series Vol. 17. International Union of Forest Research Organizations, Helsinki.

- Katsouris, C., 2004. Creditors Making ‘Major Changes’ in Debt Relief for Poor Countries. Africa Recovery, 13(2-3), 11-5.

- OECD, 2000. Agricultural Policies in Emerging and Transition Economies. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Paris.

- OECD Development Centre and AfDB, 2005. African Economic Outlook 2004/2005. Development Centre of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development and the African Development Bank. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Paris

- Oxfam America, 2002. Global Finance Hurts the Poor: Analysis of the Impact of North-South Private Capital Flows on Growth, Inequality and Poverty. Oxfam Research Report. Oxfam America, Boston.

- Sorensen, N.N., 2004. The Development Dimension of Migrant Remittances. Migration Policy Research Working Papers Series No.1 – June. International Organization for Migration.

- UN Millennium Project, 2005c. Investing in Development – A Practical Plan to Achieve the Millennium Development Goals. Earthscan, New York.

- UN-Habitat, 2003. The Challenge of Slums: Global Report on Human Settlements 2003. United Nations Programme on Human Settlements, Nairobi.

- UNCTAD, 2001. Economic Development in Africa: Performance, Prospects and Policy Issues. United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. United Nations, New York.

- UNDP, 2005. Human Development Report 2005: International cooperation at a crossroads – Aid, trade and security in an unequal world. United Nations Development Programme, New York.

- UNEP, 2005. Africa Environment Tracking – Issues and Developments. United Nations Environment Programme, Nairobi.

- UNEP, 2006. Africa Environment Outlook 2.

- Valente, M., 2005. Climate change: warnings of imminent disaster fall on deaf ears. Inter Press Service, 30 June.

- Watkins, K and Fowler, P., 2002. Rigged Rules and Double Standards – Trade, Globalization, and the Fight against Poverty. Oxfam Campaign Reports. Oxfam, Oxford.

- World Bank, 2004. World Development Indicators 2004.World Bank, Washington, D.C.

- World Bank, 2005. World Development Indicators 2005. World Bank, Washington, D.C.

- WRI, 2005. EarthTrends:The Environmental Information Portal. World Resources Institute, Washington, D.C.

- WRI in collaboration with UNEP, UNDP and the World Bank, 2005. World Resources 2005: The Wealth of the Poor – Managing Ecosystems to Fight Poverty. World Resources Institute in collaboration with the United Nations Environment Programme, the United Nations Development Programme and the World Bank.World Resources Series. World Resources Institute, Washington, D.C.

|

|

| Disclaimer: This article is taken wholly from, or contains information that was originally published by, the United Nations Environment Programme. Topic editors and authors for the Encyclopedia of Earth may have edited its content or added new information. The use of information from the United Nations Environment Programme should not be construed as support for or endorsement by that organization for any new information added by EoE personnel, or for any editing of the original content. |