Humpback whale

The Humpback whale (scientific name: Megaptera novaeangliae), is a very large marine mammal, in the family of Rorquals (Balaenoptera), part of the order of cetaceans. The Humpback is a baleen whale, meaning that instead of teeth, it has long plates which hang in a row (like the teeth of a comb) from its upper jaws. Baleen plates are strong and flexible; they are made of a protein similar to human fingernails. Baleen plates are broad at the base (gumline) and taper into a fringe which forms a curtain or mat inside the whale's mouth. Baleen whales strain huge volumes of ocean water through their baleen plates to capture food: tons of krill, other zooplankton, crustaceans, and small fish.

|

Scientific Classification Kingdom: Animalia |

|

Common Names: |

The humpback whale is renowned for its impressive leaping displays and for the mysterious singing of solitary males.

Humpback whales are among the best-studied cetaceans, and yet they are among the most mysterious. Their songs and the complex social behaviors that accompany them comprise some of the greatest incompletely understood phenomena. These songs are intricate, with up to nine musical themes. Males may sing for days, changing themes over time, but all the males from one population will sing a similar song. Humpbacks are popular subjects for whale-watching ecotourism. They are readily identified by enormous, wing-like flippers, which are far longer than in any other whale species. They are known for spectacular displays at the surface. They breach, leaping headfirst out of the water; slap the surface with a long flipper; or slam the tail flukes repeatedly. Humpbacks may be the only whales to trap or herd prey into a bunch to make feeding more efficient. They concentrate a school of fish into a stack by blowing columns of bubbles to form a circle around it, and then lunge into the mass to feed.

The robust body is blue-black in colour, with pale or white undersides. The flippers may also be white and are the largest appendage of any animal; reaching up to five metres in length. On the underside of the mouth are 12 to 36 throat grooves, which can expand when filtering water during feeding. Humpbacks have characteristically knobbly heads, covered in many raised lumps (or tubercles) and barnacles. There are two blowholes on the back and the spout of water can appear very bushy. The spreading tail flukes have a distinct indentation in the middle; as the whale undertakes a deep dive it usually arches its back (hence the common name) so that the tail flukes are raised above the water and clearly visible. The pattern on the underside of the flukes is unique to an individual and thus can be used to photo-identify and track individuals.

Contents

Physical Description

At close range, it is one of the easiest whales to identify. The most distictive external features of humpbacks are the flipper size and form, fluke coloration and shape, and dorsal fin shape. Flippers are quite long and can be almost a third of the body length. They are largely white and have knobs on the leading edge. The butterfly-shaped tail flukes bear individually distinctive patterns of gray and white, and have a scalloped trailing edge. The dorsal fin can be a small triangle or sharply falcate, and often has a stepped or humped shape; this is one source of the name humpback.

The humpback whale is a baleen whale and can be recognised as such by the plates of baleen (rather than teeth) suspended from the upper jaw and the two blowholes on the upper body. Baleen plates are usually all black with blackish bristles. Like other members of the rorqual family, the humpback has characteristic ventral pleats of skin under the eye and the relatively flat and broad jaw. There are 14 to 35 ventral pleats or grooves.

Humpbacks have the greatest relative blubber thickness for their size of any rorqual, second only to the Blue whale in absolute thickness of blubber. Blubber thickness varies at different times of the year, as well as with age and physiological condition. The dorsal fin is low and usually sits on a hump. The head has a single ridge and is covered with numerous bumps.

It is a grey-black colour dorsally and laterally, and is white underneath. Humpback whales are usually found in groups of two or three, although in feeding areas larger aggregations may develop. It is quite acrobatic and may perform full breaches, and when diving, it will often show the tail flukes. Dives may endure up to seven minutes long (Kinze, 2002).

The cerebellum of humpback whales constitutes about 20% of the total weight of the brain; the brain does not differ much from those of other mysticete whales. The olfactory organs of Humpback whales are greatly reduced and it is doubtful whether they have a sense of smell at all. Their eyes are small and adapted to withstand water pressure. Their external auditory passages are narrow, leading to a minute hole on the head not far behind the eye.

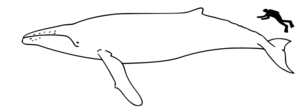

the length of the enitre body ranges from 14 to 17 metres, with females typically about one metre longer than males. body mass of adults varies from 25,000 to 45,000 kilograms, females most commonly somewhat larger than males.

Distinguishing colour characteristics of Humpbacks in the northern hemisphere exhibit dark with white belly and on flippers; however, southern hemisphere Humpbacks manifest more white colouration. Sensory knobs are evident on the head. The Humpback typically elevates its tail when diving. Variably curved dorsal fin occurs in the midback region. Knuckles or bumps along the tail stock of thin whales. Flippers may reach a length of 4.5 m. Recognition of individuals can typically be effected by the underside of flukes and body scars/markings.

Behaviour

Behaviour of Humpbacks can be divided into the following key groupings: natatorial; diurnal; motile; migratory; territorial; and social.

Humpback whales typically live in groups. This species migrates between northern and southern latitudes in accordance with the climatic cycle. Migration is largely connected with the two functions of feeding and reproduction. The Humpback regularly leaves colder waters (where the whales feed during the spring, summer and fall) to reach a winter range of shallow tropical banks (where feeding does not occur). These whales also tend to move through coastal waters during migrations when a land mass is within the direct migration route.

Humpbacks appear in large numbers in subarctic waters during the northern hemisphere spring and remain there until the summer. As the season advances, the Humpback population become less numerous. Humpbacks apparently migrate because they seek warmer water in which to bring forth their young. Pairing and mating also take place at about the same time in the warmer waters.

There is no direct evidence of territoriality. However, there are some types of preferred area sentiment by individuals or groups. This observation is supported by the seasonal return to the same feeding and breeding grounds of most Humpbacks.

Swimming speed may reach a top value of 27 km per hour, but during migration, the swimming velocity typically ranges between 3.8 to 14.3 km per hour. Whales with calves swim the slowest, whereas lone whales characteristically travel faster than those in groups.

Humpbacks dive to depths of six to seven metres, and exhibit a dive duration of 15 to 20 minutes. During diving, blows are not regular and flukes are not lifted as the whale submerges. In longer dives, the flukes are lifted and the animal surfaces between dives for about four minutes, while blowing regularly.

Humpbacks sometimes exhibit aggressive behaviors. Escort whales within a group may accompany whale-calf pairs, and can become aggressive towards other Humpbacks approaching the group. They sometimes blow bubbles from their blow-holes or mouths as an apparent screen. It is believed that most of these escorts are males.

Protective or antagonistic behaviour may involve body thrashing, horizontal tail lashing and lobtailing. This aggression may also be directed at boats that appear to approach a whale group. In general, groups of whales are more aggressive than individual whales.

Humpback whales frequently have realtionships with other animals. Humpbacks may compete with other rorquals (especially Fin whales) for food. Also, many seabirds prey upon the same food as Humpbacks. Finally, Minke whales have been observed in proximity to Humpback populations.

Reproduction

Key reproductive features of the species are: Iteroparous; Seasonal breeding; Gonochoric/gonochoristic/dioecious (sexes separate); Sexual fertilization; Viviparous births.

Sexual maturity of Humpbacks is usually reached between four and five years. In males, the penis length may be an indicator of sexual maturity. However, in some cases, puberty may proceed sexual maturity by one year. In sexually mature males, the weight of the testes and the rate of spermatogenesis increase during the breeding season, somewhat coinciding with female ovulation. After sexual maturity is reached in females, ovary weight remains fairly constant. As ovulation approaches, resting Graafian follicles on the surface of the ovaries enlarge. There generally is only one ovulation per breeding season. The breeding season is during the winter, and breeding takes place in tropical waters.

Humpbacks appear to possess a polygynous/polygamous mating system, with males competing aggressively for access to oestrous females.

Behaviors seen during courtship and feeding are as follows:

- Water slapping. A Humpback whale may slap the water with one of its pectoral flippers.

- Belly flipping. A whale may lie on its back and alternately slap the water with one flipper at a time.

- Head up. A whale may raise the dorsal portion of its head horizontally to the surface, then sink back down underwater without tavelling foward.

- Rolling corollaries of the animal include a raised flipper or flukes lifted vertiically, not horizontally

There are few actual observations of copulation in this species. The male and the female first swim in a line; they then engage in rolling, flipping, and tail fluking. Next, both dive and then surface vertically, with ventral surfaces in close contact. They emerge from the water to a point below their flippers. They then fall back onto the surface of the water together.

The gestation period lasts 11.0 to 11.5 months. During that time the embryo grows approximately 17 to 35 cm per month. Calves are born in the warm tropical waters and subtropical waters of each hemisphere. Newborns are usually four to five m long, and are suckled by their mothers for a period of about five months. The female's milk is very nutritive, containing high concentrations of fat, protein and lactose. There is no parental investment on the part of the male. Breeding usually takes place once every two years, but it may occur twice every three years. In the latter situation, lactation may last longer that five months.

If a female is impregnated shortly after parturition, pregnancy and lactation may proceed simultaneously.

Lifespan/Longevity

Maximum longevity of the species in the wild is considered to be 95 years of age.

Distribution and Movement

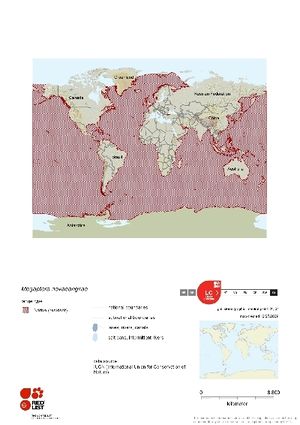

Humpback whales, live in polar and tropical waters, particularly those of the Atlantic, Arctic, and Pacific Oceans. Their range also includes the waters of the Bering Sea and the waters surrounding Antarctica.

Habitat

The habitat of Humpback whales consists of polar to tropical waters, including the waters of the Artic, Atlantic, and Pacific Oceans, as well as the Southern Ocean waters surrounding Antartica and the Bering Strait. During migration, they are found in coastal and deep oceanic waters. In the Atlantic, they generally do not come into coastal waters until they reach the lattitudes associated with Long Island, New York, and Cape Cod, Massachessetts.

Humpbacks are divided into several sub-populations. These are for the most part isolated, but with interchange in some cases. There are two stocks in the North Atlantic Ocean and two in the North Pacific. There are also seven isolated stocks in the southern hemisphere.

Habitat regions in which the Humpback is found include temperate; tropical and polar seas. Aquatic biomes inhabited by the Humpback whale include benthic habitats as well as coastal habitats.

Feeding Habits

Humpbacks are baleen whales; they have large, sieve like plates of baleen (a similar material to human hair or nails) hanging down from the inside of their mouths which function to filter planktonic organisms from the water. Individuals can open their mouths widely, due to the throat grooves, and thus engulf large quantities of water. Humpbacks often lunge into a shoal of prey, but have also been observed herding their prey into clusters or using a bubble net to effectively trap greater numbers. During this process, a number of whales will circle underwater, emitting a continuous stream of air which traps fish in the centre of the ring, the whales then surface up through their net of air, gorging on the prey contents within. During the summer months, humpbacks must feed intensely, as they do not feed again during either the migration or the time spent in tropical breeding grounds.

Like Minke whales and and Fin whales, humpbacks are generalized feeders. They are highly mobile and opportunistic. Humpbacks feed upon plankton, the plant and animal life at the surface of the ocean's water, or upon fish in large patches or schools. Because of this, Humpbacks are classified as "swallowers" and not "skimmers." Animal prey includes both fish and zooplankton. They specifically may consume commercially exploited fishes. Feeding by Humpbacks takes place during the summer.

Pleurogrammus azonus and Cololabis saira are the most commonly found fish prey of humpbacks in the eastern North Pacific Ocean. The former is considered one of the favorite foods of Humpback whales in waters off the Western Aleutians and South of the Amchitka Islands. In addition, humpbacks in the North Pacific and the Bering Sea eat euphausiids (krill), mackerel, sand lance, Ammodytes americanus, capelin and herring.

Fish species comprise about 95% of the diet of North Atlantic Humpbacks. Those Humpbacks living in the Atlantic Ocean, specifically near Cape Cod and Greenland, also eat sand lance, herring and pollock. Humpbacks near Australia and in the Antartic also feed on euphausiids.

Typically, these whales take both food and water into their mouths. Large volumes can be accomodated because the ventral grooves in the throat allow for expansion. Once the mouth is full, it is closed and the water is pressed out. Meanwhile, the food is caught in the baleen plates and is then swallowed. This process is aided by the internal mechanism of rorqual feeding--the tongue.

Humpbacks have five main feeding behaviors (The first three are more commonly observed than the last two):

- Ring of foam. Humpbacks have an elaborate feeding behavior in which they lie on the ocean's surface and swim in a circle. While doing so, they strike the water with their flukes forming a ring of foam, which surrounds their prey. Then, they dive under the ring and resurface in the center with mouth open, allowing them to capture the prey within the ring.

- Lunging. Humpbacks often feed by swimming vertically or obliquely up through aggregations of plankton or fish. This occurs only when their food is abundant. In addition, some variation may occur by means of lateral and/or inverted lunging.

- Bubble behavior. When these whales use underwater exhalation to create bubble clouds and bubble columns. Bubble clouds are large inter-connected masses of bubbles formed by one underwater exhalation. Clouds concentrate or herd a mass of prey. Feeding is presumed to occur underwater. Subsequently the Humpback rises slowly to the surface within the bubble cloud. After several blows and some shallow diving, the manuever is repeated. Bubble clouds appear to assist in prey detection or capture by immobilizing or confusing prey. Bubble clouds may cause a jumping response among the prey, helping the whale to detect the prey, or it may disguise the whale from the prey. Bubble columns are formed as a humpback swims underwater in a broad circle while exhaling. An individual column may form rows, semicircles, or complete circles. These circles act like a seive net, concentrating or herding the prey.

- Tail slashing. In this method of feeding, the individual whale swims in a large circle while slashing its tail through the water. The actual feeding takes place thereafter in the center of the turbulence.

- Inside loop behavior. A whale can make a shallow dive, while hitting the water with its fluke as it submerges. A 180 degree roll is then rapidly executed as the animal makes a sharp U turn (the inside loop) and then lunge feeds slowly through the turbulent area created by its flukes. The whale feeds beside the area of turbulence.

- Flick-feeding. this occurs only when whales eat euphausiids.

At times, humpbacks combine some of these methods, for example, combining bubble feeding and tail slapping (lobtailing), as they feed on sand lance.

It is important to note that no Humpback younger than two years old uses the tail slapping method, although they are weaned from their mothers at one year. However, rudimentary lobtail feeding has been witnessed several times among older post-weaning young. In addition, no difference has been noted in the frequency of lobtail feeding between the sexes.

Economic Importance for Humans

Humpbacks have historically had significant economic importance to humans. They were one of the nine species hunted intensively by whalers. They were at times the most important constituent of the catch of modern whalers. Their oil was in demand as a type of burning oil for lamps, and as a lubricant for machinery. Humpback Whale oil was also used as a raw material for margarine and as a component of cooking fat. The whale meat was processed for human consumption and made into animal feed. Meal made from Humpback Whale bones was used as fertilizer.

However, these cetaceans are no longer hunted extensively. They do continue to have some economic impact, as ecotourism and whale sighting tours are quite popular in many coastal areas. Whale watching tours to see these magnificent animals are popular throughout the world from Alaska to Hawaii and Japan to Australia. In the northwest Atlantic particularly, these have worked closely with scientists providing valuable photo identification of individuals that has helped to uncover some of the mysteries surrounding their impressive migration. Humpback whales are the most studied of the large whales, but little is still known about some aspects of their behaviour and about population dynamics, further research and monitoring is therefore needed to safeguard these awe-inspiring acrobats of the sea.

Threats and Conservation Status

In the early part of the twentieth century, during the modern whaling era, humpback whales were highly vulnerable due to their tendency to aggregate on the tropical breeding grounds and to come close to the shore on the northern feeding grounds. More than 60,000 humpbacks were killed between 1910 to 1916 in the southern hemisphere, and there were other peaks of exploitation in the 1930's and 1950's. In the North Pacific, there were peak catches of over 3,000 in 1962 to 1963.

In order to combat the problem of depletion, catching humpback whales was prohibited in the Antartic in 1939, although that plan was abandoned in 1949. In the southern hemisphere, hunting was banned in 1963. In the North Atlantic, hunting was banned in 1956. Finally hunting was banned in the North Pacific in 1966. In 1985 the International Whaling Commission instituted a moratorium on commercial whaling.

The IUCN Red List of Endangered Species notes that the "available population estimates total more than 60,000 animals". The healthiest populations occur in the western north Atlantic Ocean. A few other areas in which there are small populations include the waters near Beguia, Cape Verde, Greenland, and Tonga. Global humpback populations have begun to strengthen, although this species is still a conservation concern.

The IUCN Red List classifies the Humpback as Vulnerable; the USA categorises this taxon as an endangered species. CITES lists the species in its Appendix I.

Further Reading

- Megaptera novaeangliae, Encyclopedia of Life (accessed February 20, 2011)

- Reilly, S.B., Bannister, J.L., Best, P.B., Brown, M., Brownell Jr., R.L., Butterworth, D.S., Clapham, P.J., Cooke, J., Donovan, G.P., Urbán, J. & Zerbini, A.N. 2008. Megaptera novaeangliae. In: IUCN 2010. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2010.4. . Downloaded on 01 March 2011.

- WDCS, The Whale and Dolphin Conservation Society (March, 2003)

- Carwardine, M. (1995) Whales, Dolphins and Porpoises. Dorling Kindersley, London.

- Convention of Migratory Species (October, 2008)

- Zip Code Zoo (April, 2008)

- MarineBio.org (April, 2008)

- Macdonald, D. (2001) The New Encyclopedia of Mammals. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- Centre for Cetacean Research and Conservation (March, 2003)

- Bruyns, W.F.J.M., (1971). Field guide of whales and dolphins. Amsterdam: Publishing Company Tors.

- Howson, C.M. & Picton, B.E. (ed.), (1997). The species directory of the marine fauna and flora of the British Isles and surrounding seas. Belfast: Ulster Museum. Museum publication, no. 276.

- Jefferson, T.A., Leatherwood, S. & Webber, M.A., (1994). FAO species identification guide. Marine mammals of the world. Rome: United Nations Environment Programme, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

- Kinze, C. C., (2002). Photographic Guide to the Marine Mammals of the North Atlantic. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- NBN (National Biodiversity Network), (2002). National Biodiversity Network gateway. (accessed 2008-10-31)

- OBIS, (2008). Ocean Biogeographic Information System. (accessed 2008-10-31)

- Reid. J.B., Evans. P.G.H., Northridge. S.P. (ed.), (2003). Atlas of Cetacean Distribution in North-west European Waters. Peterborough: Joint Nature Conservation Committee.

- Authors:Randall R. Reeves, Brent Stewart, Phillip j. Clapham, James A. Powell

- Banks, R. C., R. W. McDiarmid, A. L. Gardner, and W. C. Starnes. 2003. Checklist of Vertebrates of the United States, the U.S. Territories, and Canada

- Banks, R. C., R. W. McDiarmid, and A. L. Gardner. 1987. Checklist of Vertebrates of the United States, the U.S. Territories, and Canada. Resource Publication, no. 166. 79

- Borges, P.A.V., Costa, A., Cunha, R., Gabriel, R., Gonçalves, V., Martins, A.F., Melo, I., Parente, M., Raposeiro, P., Rodrigues, P., Santos, R.S., Silva, L., Vieira, P. & Vieira, V. (Eds.) (2010). A list of the terrestrial and marine biota from the Azores. Princípia, Oeiras, 432 pp.

- Borowski, G.H. 1781. Gemeinnuzige Naturgeschichte des Thierreichs. Gottlieb August Lange, Berlin, 1:21.

- Clapham, Phillip J., and James J. Mead. 1999. Megaptera novaeangliae. Mammalian Species, no. 604. 1-9

- David Macdonald (1985) The Encyclopedia of Mammals. Facts on File: New York.

- Dr. David Macdonald, ed. 1985. Humpback whale. The Encyclopedia of Mammals. Facts on File Press, New York.

- Encyclopedia Britannica, vol 23. 1962. Cetacea. William Benton, Publisher, Chicago.

- Encyclopedia Britannica, vol 5. 1962. Cetacea. William Benton, Publisher, Chicago.

- Felder, D.L. and D.K. Camp (eds.), Gulf of Mexico–Origins, Waters, and Biota. Biodiversity. Texas A&M Press, College Station, Texas.

- Fish, F. E.; Battle, J. M. 1995. Hydrodynamic design of the humpback whale flipper. J Morphol. 225(1): 51-60.

- Foy, Sally; Oxford Scientific Films. 1982. The Grand Design: Form and Colour in Animals. Lingfield, Surrey, U.K.: BLA Publishing Limited for J.M.Dent & Sons Ltd, Aldine House, London. 238 p.

- Gordon, D. (Ed.) (2009). New Zealand Inventory of Biodiversity. Volume One: Kingdom Animalia. 584 pp

- Hershkovitz, Philip. 1966. Catalog of Living Whales. United States National Museum Bulletin 246. viii + 259

- IUCN (2008) Cetacean update of the 2008 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.

- IUCN Red Book, NMFS/NOAA Technical Memo

- J.R. Beddington, R.J.H. Beverton, and D.M. Lavigne, eds.1985. Megaptera novaengliae. Marine Mammals and Fisheries. George Allen Unwin, London.

- Jan Haelters

- Jefferson, T.A., S. Leatherwood and M.A. Webber. 1993. Marine mammals of the world. FAO Species Identification Guide. Rome. 312 p.

- Keller, R.W., S. Leatherwood & S.J. Holt (1982). Indian Ocean Cetacean Survey, Seychelle Islands, April to June 1980. Rep. Int. Whal. Commn 32, 503-513

- Koukouras, Athanasios (2010). check-list of marine species from Greece. Aristotle University of Thessaloniki. Assembled in the framework of the EU FP7 PESI project.

- MEDIN (2011). UK checklist of marine species derived from the applications Marine Recorder and UNICORN, version 1.0.

- Mead, James G., and Robert L. Brownell, Jr. / Wilson, Don E., and DeeAnn M. Reeder, eds. 2005. Order Cetacea. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference, 3rd ed., vol. 1. 723-743

- Miklosovic, D. S.; Murray, M. M.; Howle, L. E.; Fish, F. E. 2004. Leading-edge tubercles delay stall on humpback whale (Megaptera novaeangliae) flippers. PHYSICS OF FLUIDS. 16(5):

- National Audubon Society Guide to Marine Mammals of the World

- North-West Atlantic Ocean species (NWARMS)

- Perrin, W. (2011). Megaptera novaeangliae (Borowski, 1781). In: Perrin, W.F. World Cetacea Database. Accessed through: Perrin, W.F. World Cetacea Database (accessed 2011-02-05)

- Ramos, M. (ed.). 2010. IBERFAUNA. The Iberian Fauna Databank

- Rice, Dale W. 1998. Marine Mammals of the World: Systematics and Distribution. Special Publications of the Society for Marine Mammals, no. 4. ix + 231

- Ridgway, S. H. Ridway and Sir Richard Harrison, eds.1985. Humpback whale. Handbook of Marine Mammals. Academic Press Harcourt Brace, London.

- The New Encyclopedia Britannica, vol 12. 1989. Cetacea. Univeristy of Chicago Press, Chicago.

- UNESCO-IOC Register of Marine Organisms

- Weinrich, M. T., M. R. Schilling, and C. R. Belt. Evidence for acquisition of a novel feeding behaviour: lobtail feeding in humpback whale, Megaptera novaeangliae.Animal Behaviour, 44(6):1059-72. S

- Wiley, D. N. and P. J. Clapham. Does maternal condition affect the sex ratio of offspring in humpback whales? Animal Behaviour,46(2):321-4.

- Wilson, Don E., and DeeAnn M. Reeder, eds. 1993. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference, 2nd ed., 3rd printing. xviii + 1207

- Wilson, Don E., and F. Russell Cole. 2000. Common Names of Mammals of the World. xiv + 204

- Wilson, Don E., and Sue Ruff, eds. 1999. The Smithsonian Book of North American Mammals. xxv + 750

- van der Land, J. (2001). Tetrapoda, in: Costello, M.J. et al. (Ed.) (2001). European register of marine species: a check-list of the marine species in Europe and a bibliography of guides to their identification. Collection Patrimoines Naturels, 50: pp. 375-376