Hawaiian monk seal

The Hawaiian monk seal (scientific name: Monachus schauinslandi) is one of nineteen species of marine mammals in the family of true seals. Together with the families of eared seals and walruses, True seals form the group of marine mammals known as pinnipeds.

Hawaiian monk seals are the only true seals to be found year-around in tropical waters.

Contents

Physical description

After the annual moult, this monk seal is a silvery grey colour on the back, with cream colouring on the throat, chest and underside. Over time the coat looks brown above and yellow below; males, and some females, turn almost black with age. Certain individuals may have a red or green tinge or spots due to algal growth. Pups measure about one metre at birth and have a silky black coat, which moults after around a month into the silvery adult-like fur.

| Conservation Status |

|

Scientific Classification Kingdom: Anamalia (Animals) |

Reproduction

Males outnumber females by a factor of three to one, so that, when a group of males spot a female in estrus, they sometimes mob her, sometimes inflicting serious or mortal wounds in their eagerness to mate. Mating takes place underwater.

Only 60- 70% of adult females give birth in a given year and tend to give birth to a single pup. Most births take place from March-June after a gestation of 11 months (including a period of delayed implantation). Pups weigh 36 lbs at birth and are approximately one metre long. They have soft, black hair that is moulted after three to five weeks into a coat that is silver-blue dorsally and silvery-white ventrally. Pups are weaned at about six weeks.

Females give birth and suckle their young on sandy beaches with or without shade, and sometimes on the rocky shores of Necker Island. Females will sometimes foster another female's offspring. Approaches by large dominant males characteristically elicit submissive behavior from other seals. Females with pups are extremely sensitive to disturbances; they will threaten, or if necessary, attack invaders. These aggressive interactions among females often lead to pups switching mothers.

Females fast for two to three months subsequent to weaning their young. The female is typically sexually mature at about five to six years of age.

Behavior

Monk seals are predominately solitary although females with young may be observed near each other due to limited areas offering the preferred habitat type for pupping.

Hawaiian monk seals have a similar fat content to their relatives that inhabit cooler, polar waters and have developed behavioural adaptations to cope with the warmth of their tropical habitat; they are mainly nocturnal, spending the day hauled out on sandy beaches often wallowing in wet sand by the waters edge. Hawaiian monk seals do not migrate, although certain individuals may disperse over long distances. The Hawaiian monk seal is chiefly nocturnal, resting during daytime heat and diving for food at night.

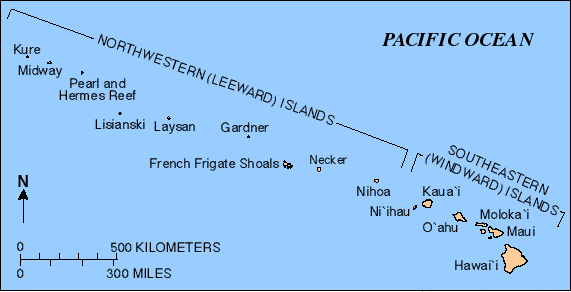

Distribution

The main reproductive and foraging sites are on and around the largely uninhabited and remote Northwestern Hawaiian Islands of French Frigate Shoals, Laysan Island, Lisianski Island, Pearl and Hermes Reef, Midway Atoll and Kure Atoll. Monk seals also breed in lower numbers at Necker and Nihoa Islands in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands and in the main Hawaiian Islands, and have also been seen at a few sites outside of the Hawaiian Archipelago

Habitat

As preferred habitat, Hawaiian monk seals frequent reefs (for feeding), beaches (for basking and delivering their young), and coves. They spend a great amount of time wallowing in damp sand on the foreshore at the water's edge, to moderate body temperature and engage in social and mating activities.

Feeding habits

Hawaiian monk seals feed on a variety of marine animals from fish, including eels, to cephalopods such as octopus and squid. They forage at depths of up to 100 metres, but are known to dive to 500 metres, and may travel large distances to seek out foraging locations.

Conservation status

Monk seals are "genetically tame" and therefore easy to find and kill. This makes them vulnerable to rapid depletion. During the 1800s, Hawaiian monk seals were persecuted for their meat, hides and oil; their habitat was also disturbed by bird guano and feather collectors. In 1824, the last monk seal in the Pacific was thought to have been killed. They obviously survived, probably on beaches difficult to access from the sea. The species has continued to decline due to disturbance by humans, shark predation and disease. They were declared endangered in 1976. Downward counts in the population seemed to be reversed in the 1980's, and the count is now approximately 1,200 individuals.

The greatest threats are the disturbance of the mother during her breeding season (which causes her to find a new, less preferred site to give birth and nurse), ciguatera poisoning from reef fishes, and shark attacks. All but two of the Leeward Islands are protected from exploitation under the Hawaiian Islands National Wildlife Refuge. Of the protected islands, three are inhabited by humans: Green Island in Kure Atoll, Sand Island in Midway Atoll, and Tern Island in French Frigates Shoal.

Major colonies are surveyed annually and beach counts help to give an indication of the state of each breeding population; flipper tagging has been carried out since the early 1980s. The Northwest Hawaiian Islands lobster fishery was closed in the year 2000, and this action may assist in augmenting prey availability. In 2000, the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands Coral Reef Ecosystem Reserve was established, which will aid in the habitat protection for this unique seal.

Economic importance to humans

These seals were an important part of the Hawaiian economy in the nineteenth century, when they were actively hunted for their meat and fur. Today they are no longer of great economic importance, because of their dwindling numbers and because the demand for seal meat and seal by-products has diminished. Hawaiian monk seals are held in captivity in the San Diego Zoo, Waikiki Aquarium, and Sea Life Park, where they draw the attention of tourists from all over the globe.

Image Source: Wikimedia Commons

Image Source: Wikimedia Commons

Further reading

- Monachus schauinslandi Matschie, 1905 Encyclopedia of Life (accessed April 17, 2009)

- Monachus schauinslandi, Lambert, J. and I. Rouse, 1999, Animal Diversity Web (accessed April 17, 2009)

- Hawaiian monk seal , Seal Conservation Society (accessed April 17, 2009)

- Monachus schauinslandi, IUCN Red List of Threatened Species (accessed April 17, 2009)

- The Pinnipeds: Seals, Sea Lions, and Walruses, Marianne Riedman, University of California Press, 1991 ISBN: 0520064984

- Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals, Bernd Wursig, Academic Press, 2002 ISBN: 0125513402

- Marine Mammal Research: Conservation beyond Crisis, edited by John E. Reynolds III, William F. Perrin, Randall R. Reeves, Suzanne Montgomery and Timothy J. Ragen, Johns Hopkins University Press, 2005 ISBN: 0801882559

- Walker's Mammals of the World, Ronald M. Nowak, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999 ISBN: 0801857899

- Hawaiian monk seal, MarineBio.org (accessed April 17 , 2009)