Garamba National Park, Democratic Republic of Congo

Contents

- 1 IntroductionThe Garamba National Park (3°45'-4°41'N, 28°48'-30°00'E) is a World Heritage Site located in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). Immense savannas, grasslands (Garamba National Park, Democratic Republic of Congo) and woodlands, threaded with gallery forests along river banks and swampy depressions, protect a wide range of animals, especially the four large mammals, elephant, giraffe, hippopotamus and above all the endangered (IUCN Red List Criteria for Endangered) northern white rhinoceros. This is much larger than the black rhino, and only some thirty individuals remain. It is one of the world's twelve most threatened animals.

- 2 Threats to the Site

- 3 Geographical Location

- 4 Date and History of Establishment

- 5 Area

- 6 Land Tenure

- 7 Altitude

- 8 Physical Features

- 9 Climate

- 10 Vegetation

- 11 Fauna

- 12 Cultural Heritage

- 13 Local Human Population

- 14 Visitors and Visitor Facilities

- 15 Scientific Research and Research Facilities

- 16 Conservation Value

- 17 Conservation Management

- 18 IUCN Managment Category

- 19 Further Reading

IntroductionThe Garamba National Park (3°45'-4°41'N, 28°48'-30°00'E) is a World Heritage Site located in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). Immense savannas, grasslands (Garamba National Park, Democratic Republic of Congo) and woodlands, threaded with gallery forests along river banks and swampy depressions, protect a wide range of animals, especially the four large mammals, elephant, giraffe, hippopotamus and above all the endangered (IUCN Red List Criteria for Endangered) northern white rhinoceros. This is much larger than the black rhino, and only some thirty individuals remain. It is one of the world's twelve most threatened animals.

Threats to the Site

The Park was placed on the List of the World Heritage in Danger for the first time between 1984 and 1992 because of a serious decline in the white rhinoceros population. After measures taken by the World Heritage Committee, IUCN, WWF, the Frankfort Zoological Society and the national authorities, the population recovered from fifteen to around thirty-five animals. In 1996 civil disorder in the east of the country led to widespread attacks on the Park's infrastructure. Equipment was looted, several staff deserted and the site was returned to the List of World Heritage in Danger. Threats to the Park will not be overcome until there is law and order in the area. However, the remaining staff are once again resisting poaching threats effectively.

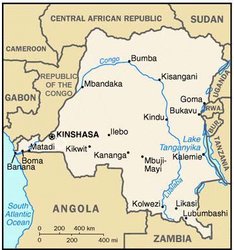

Geographical Location

Map of the Democratic Republic of Congo. The Garamba National park is located on the Sudanese border. (Source:U.S Department of State)

Map of the Democratic Republic of Congo. The Garamba National park is located on the Sudanese border. (Source:U.S Department of State) In the far northeast of the Democratic Republic of Congo on the Sudan border: 3°45'-4°41'N, 28°48'-30°00'E.

Date and History of Establishment

- 1938: Instituted by decree as Garamba National Park.

- 1969: The National Institute for Nature Conservation received responsibility for it by Decree 69/72.

- 1975: The Institut Zaïrois pour la Conservation de la Nature (IZCN) made responsible for the park under the State Commission for the Environment, Nature Conservation and Tourism.

Area

492,000 hectares (ha). Contiguous on the northeast with the proposed Lantoto national park in Sudan. In the DRC, surrounded by three hunting areas totaling about 1,000,000 ha: Reserve Azande to the west, Reserve Mondo-Missa to the east and Reserve Gangala na Bodio to the south.

Land Tenure

Government, in Uele district. Administered by the Institut Congolais (formerly Zairois) pour la Conservation de la Nature (ICCN).

Altitude

710 meters (m) to 1,061 m.

Physical Features

A vast undulating plateau parkland, principally long-grass and bush savanna, shaped by fire. It slopes southwest from the watershed between the Nile and Congo rivers, part of an ancient peneplain interrupted by mostly granitic inselbergs, threaded by gallery forests, with large marshland depressions. The main rivers are the Dungu on the southern, and the Aka along the western boundaries, and the Garamba within the Park.

Climate

The tropical climate has a semi-moist rainy season from March to November with temperatures between 20° and 30° C, and a dry period from November to March, when temperatures range from 6°C to 39°C and hot dry north-easterly winds are common. The mean annual rainfall averages about 1260 millimeter (mm). .

Vegetation

The park's position, between the Guinean and [[Sudan]ese] biogeographic realms, makes it particularly interesting. It covers three biomes: gallery forest with forest clumps and marshland; aquatic and semi-aquatic associations; and savannas ranging from dense savanna woodland to nearly treeless grassland. The densely wooded savanna, relict gallery forests, and the papyrus marshes of the north and west give way in the center to more open tree-bush savanna, which merges into the long grass savanna that covers most of the park.

The savanna woodlands are often dominated by Combretum spp. and Terminalia mollis. Accompanying dominant species include Hymenocardia acida, Bauhinia thonningii, Dombeya quinqueseta, Acacia, Grewia and Bridelia spp., Albizzia glaberrima and Erythrina abyssinica. Gallery forests and forest patches contain Erythrophleum suaveolens, Chlorophora excelsa, Irvingia smithii, Khaya anthotheca, K. grandifoliola, Klainedoxa sp., Ficus spp. and Spathodea campanulata. Sudanian woodland grows towards the north-eastern part of the park, which is dominated by Isoberlinia doka with scattered Uapaca somon. Marshlands are dominated by Cyperus papyrus and Mitragyna rubrostipulacea.

The main species of the long-grass savanna are Loudetia arundinacea and various Hyparrhenia species, which in September can grow over 2 m high, with the tallest grass Urelytrum giganteum up to 5 m. There are occasional scattered Kigelia africana and Vitex doniana trees. It is dissected by numerous small rivers with valley grasslands and papyrus swamps.

There are approximately 1,000 vascular plant species, of which some 5% are endemic. Useful plants found growing in the park include Erythrophleum guineense, Nauclea latifolia, Terminalia mollis (building material), Vitex doniana (medicinal); Spathodea campanulata (ornamental); Cyperus papyrus, Thalia welwitschii (ropes, mats, baskets); Hymenocardia acida, Hyparrhenia diplandra, Loudetia phragmitoides, L.simplex, Pennisetum simplex (fuel), P. purpureum, Hallea stipulosa, Imperata cylindrica, Khaya anthotheca, and Leersia hexandra.

Fauna

This is a photo of a white rhinoceros. These animals are killed for their horns, which are sold on the black market for exorbitant amounts of money. (Source: Monroe County Government)

This is a photo of a white rhinoceros. These animals are killed for their horns, which are sold on the black market for exorbitant amounts of money. (Source: Monroe County Government) The park contains probably the last viable natural population of square-lipped or northern white rhinoceros Ceratotherium simum cottoni (CR). Rhino numbers fell from approximately 1,000 animals in 1960 to 490 (+/-270) in 1976, to 13-20 in 1983 and about 15 individuals in 1984 due to intensive poaching. In 1991, there were thought to be 31, and in 1996 there were 30. Elephant Loxodonta africana (EN) is a unique population representing an intermediary form on the cline between the forest and savanna sub-species, L. africana cyclotis and L. africana africana. The population was reduced from over 20,000 in the late 1970s to 8,000 in 1984. The 1994 estimate is 11,175 . Other mammals include northern savanna giraffe Giraffa camelopardalis congoensis (occuring nowhere else in Zaïre), hippopotamus Hippopotamus amphibius, buffalo Syncerus caffer (LR), which was reduced from 53,000 in 1976 to 25,000 in 1995, hartebeest Alcelaphus buselaphus lelwel (LR), kob Kobus kob (LR), waterbuck K. ellipsiprymnus (LR), chimpananzee Pan troglodytes (EN), olive baboon Papi anubis, colobus Colobus sp., vervet Cercopithecus aethiops, de Brazzas C. neglectus and four other species of monkey, two species of otter, five species of mongoose, golden cat Felis aurata, leopard Panthera pardus, lion P. leo (VU), warthog Phacochoerus aethiopicus, bushpig Potamochoerus porcus, roan antelope Hippotragus equinus (LR), and six other antelope species.

Cultural Heritage

No information is available.

Local Human Population

None in the park in 1989, and sparse outside it, but overrun by neighboring Sudani refugees.

Visitors and Visitor Facilities

The Park is remote and its facilities need both renovation and promotion. There was visitor accommodation at both Nagero and Gangala-na-Bodio. Construction of pontoons, improved roads and maintenance, development of the rangers' stations, a controlled grass burning regime to improve visibility and good interpretive material should facilitate visitors' use of the park. But after the civil disturbances in both the DRC and Sudan, income from foreign tourists virtually ceased.

Garamba is famous for the African Elephant Domestication Centre at Gangala-na-Bodio, in the south-west of the park where four old trained elephants remain. The Garamba Rehabilitation Project caught more young elephants to be trained for visitor use, and a successful tourist operation was tried, using saddles for elephant-back safaris which could become a unique attraction.

Scientific Research and Research Facilities

An expedition in the early 1950s gathered much information, mainly taxonomic, which is available in a series of publications. In the early 1970s, an Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations (FAO) project to improve the park gathered information on the rhinoceros and flew an aerial census of large mammal species. In 1983 an aerial and ground census was carried out under the auspices of Zaire National Parks Institute (IZCN) along with IUCN, WWF,Frankfurt Zoological Society (FZS) and United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) and an FAO project. From 1984 as part of a rehabilitation project the rhino population was investigated and monitored, general ecosystem monitoring was carried out, including aerial counts, vegetation description and habitat mapping, a check list of birds and preliminary studies on the domestic elephants. An experimental burning program was also tested.

Daily meteorological observations were made in conjunction with the Institut National pour l'Etude et la Recherche Agronomique, and a herbarium collection was started. The research team consisted of an expatriate, three Congolese researchers and two research assistants. The research covered a detailed study of rhino behavior and feeding ecology, feeding and habitat use by wild elephants which was compared with the information gathered in the domestic elephant studies, also research into soil-vegetation-termite relationships. Regular internal reports were produced. An ecosystem resource inventory was compiled to provide data for management, and the material written up for publication. A research office existed, though with limited scientific facilities due to shortage of funds.

Conservation Value

This area of savanna, grassland and woodland, interspersed with gallery forest and swampy depressions was established primarily to protect the northern white rhinoceros and northern savanna giraffe, also elephant and hippopotamus. The variety of its [[habitat]s] is the reason for the wide diversity of other wildlife.

Conservation Management

The park is under the overall control of the International Center for Conflict and Negotiation (ICCN) headquarters station at Nagero, with a secondary station at Gangala-na-Bodio which also oversees the southern and western hunting reserves. The three surrounding hunting areas which total about 1,000,000 ha, are intended as buffer zones: Gangala-na-Bodio, in the south, Mondo-Missa, southeast, controlled from Nagero Station, and Azande in the northwest. Following the deterioration in Park conditions during the 1970s and 1980s, a rehabilitation project sponsored by IUCN, WWF, the Frankfort Zoological Society and UNESCO worked with IZCN staff in 1984 to restore the infrastructure of the park and revive anti-poaching activity. After evaluation of this project in 1996, a new project design and draft management plan were produced. This provided equipment and expertise and carried out construction, maintenance, training and monitoring (Environmental monitoring and assessment). The collaboration increased the intensity and effectiveness of poaching surveillance. Salaries and other support were subsequently increased and the guards' weapons modernized.

Previous foot patrols from permanently-manned posts around the edges of the park had proved difficult to control; the guard force also relied so much on the local people for supplies that it became hard for them to enforce the law. A new road network and five new patrol posts were therefore constructed. Most posts are on hills to detect the smoke from poachers' meat-drying fires, and have radio contact with the headquarters. Mobile foot patrols leave from the main stations in rotation, in two patrols of eight guards each at any one time within the rhino area. In 1996, following renewed poaching, much of it internal, radio-transmitter equipment was installed in each rhinoceros horn to help guide anti-poaching patrols to where they may be needed.

Management Constraints

Image of poached elephant tusks. (Source: Center for Conservation Biology University of Washington)

Image of poached elephant tusks. (Source: Center for Conservation Biology University of Washington) There have been two main reductions in [[population]s] of commercially valuable species. The first was during the political disturbances in the 1960s, when it was estimated that the rhino population fell from 1,000-1,300 to about 100, and elephants were also poached. Rhino numbers then rose again to about 400-800. The second major loss to poaching was in the late 1970s when the demand and poaching for ivory and rhino horn increased dramatically over most of Africa. The Park was particularly vulnerable, being very far from support by the headquarters in Kinshasa and on the border of three countries suffering civil unrest with its accompanying availability of weapons. In 1984 the site was placed on the List of World Heritage in Danger for fear that the rhinoceros population of 15 animals would be eliminated by poaching. The Rehabilitation Project successfully controlled the problem, the rhino population doubled, and the park was taken off the Danger List in 1992.

However, in 1991, 80,000 well armed refugees from the war in Sudan began to settle in the hunting areas around the Park which greatly increased internal poaching for bushmeat. Buffalo were the main target, while elephants were poached for ivory. Nearly all the game in the north half of the Park was wiped out. After the poaching of two rhinoceros for their horn in early 1996 and the killing of three park rangers on duty, the Park was again placed on the List of World Heritage in Danger. The recent political and economic instability within the country placed great strain on the Park staff and infrastructure. In 1997 the guards were disarmed and all the Park's facilities were looted. There were no vehicles, fuel or rations to prevent intensified poaching by the Sudanese. However, in 1999 some payment of salaries was made and the guards, partially re-armed and re-equipped, were able to begin to restore order once more. By 2001, funded by the UNESCO/DRC/UNF Project, surveillance was regular, the state of conservation in the Park was relatively good once again and a total of 300 northern white rhinos reported.

Staff

Core staff include: Conservateur Principal at Nagero, Conservateur at Gangala-na-Bodio, and about 190 guards and 50 laborers throughout the park. Under the IUCN/WWF Project which started in 1984, two expatriate advisers and one expatriate in the ancillary research section are implementing the program and training their Congolese counterparts and staff.

Budget

The initial annual budget for the park was US$45,000; and for the Project, Sfr400,000. By 1987 WWF had provided over one million Swiss francs for the protection of rhino. In 1999 the United Nations Fund promised US$4,86,600, two-thirds of it outright, to compensate staff and pay salaries and allowances for all five D.R.C. World Heritage Sites between 2000 and 2004: US$30,000 for salaries and new patrolling equipment came to the Reserve via the International Rhino Foundation. In 2000 the Belgian government also promised US$500,000 for the five parks from 2001-2004.

IUCN Managment Category

- II National Park

- Natural World Heritage Site, inscribed in 1980. Natural Criteria iii, iv Listed as World Heritage in Danger in 1984-92 and again in 1996 because of decimation of rhinos, heavy poaching and destruction of infrastructure resulting from the civil war in Sudan.

Further Reading

- Anon. (not dated). Four Wonders of Nature: Four World Heritage Sites in Zaire. Vanmelle, Belgium.

- Anon. (1987). Garamba National Park: Rehabilitation Programme. Annual Report. IUCN, Eastern Africa. 18 pp.

- Davis, S., Heywood, V. & Hamilton, A.,(eds) (1994) Centres of Plant Diversity Vol.1. WWF / IUCN, IUCN, Cambridge, UK. ISBN: 283170197X

- De Saeger, H. (1954). Introduction; Exploration du Parc National de la Garamba. Mission H. De Saeger. Inst. Parcs. Nat. Congo. Belge: pp.1-107.

- Draulens ,D. & van Krunkelsven, E. (2002). The impact of war on forest areas in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Cambridge University Press 36 (1): 35-40.

- Farmer, L. (1996). Black and white case for protection. WWF News, Summer 1996.

- Greeff, J. (1996). Training Needs Assessment: Garamba National Park, Zaire. WWF / IUCN.

- Hillmann, K., Borner M., Mankoto ma Oyisenzoo, Rogers, P. & Smith, F.(1983). Aerial Census of the Garamba National Park, Zaire, March 1983, with Emphasis on the Northern White Rhinos and Elephants. Report to IUCN, WWF, FZS and UNEP.

- Hillmann-Smith, K. (1989). Ecosystem Resource Inventory, Garamba National Park. Internal Report to IZCN, IUCN, WWF, FZS & Unesco.

- Hillmann-Smith, K. et al. (1994). Parc Nationale de la Garamba. Checklist of Birds. Internal report.

- Hillmann-Smith, K.,de Merode, A.,Nicholas,A.,Buls,B. & Nday,A.(1995). Factors effecting elephant distribution at Garamba National Park and surrounding reserves,Zaire.Pachyderm 19(4):301-22.

- Hillman-Smith, F.& K. (1998). Garamba National Park Project. Annual Report.

- IUCN/WWF Project 1954. Garamba National Park.

- IUCN (1985). Threatened natural areas, plants and animals of the world. Parks 10: 15-17.

- IUCN/WWF (1985). Rapport d'une mission au Zaïre et Rwanda. IUCN / WWF, Gland, Switzerland.

- IUCN (1997) State of Conservation of Natural World Heritage Properties. Report prepared by IUCN for the 21st Session of the World Heritage Bureau, 23-28th June, Paris France.

- Kabala M. (1976). La conservation de la Nature au Zaïre. Aspects. Edition Lokola, Kinshasa: 237-42.

- Karesh, W. (1996) Rhino relations. Wildlife Conservation, 99(2):38-43.

- Maldague, M. (1979). Parc National de la Garamba. Recommandations d'Aménagement. Unesco / WCNH, Zaïre.

- Mackie, C. (1984). A Preliminary Evaluation of Conservation Development in Garamba National Park. Recent Poaching Developments in Garamba National Park. Reports submitted to IUCN/WWF/FZS.

- Mackie, C. (1988). Garamba National Park, Protection of Rhino. WWF Project No. 1954. In WWF List of Approved Projects, Vol. 4: Africa and Madagascar. WWF, Gland, Switzerland.

- Pierret, P.,Grimm,M.,Petit,J.& Dimoleyele-ku-Gilima Buna (1976). Contribution a l'Etude des Grands Mammifères du PNG et Zones Annexes. FAO Document de Travail No.4 ZAI/70/001. 49 pp.

- Project Proposal (1983) to IUCN for Rehabilitation Rrogramme for Garamba National Park.

- Rogers, P.,Hillman,K.,Mbaelele M. & Ma-Oyisenzoo, M. (1983). Développement et Conservation du Parc National de la Garamba.. Rapport de Terrain 01/84, FAO Kinshasa.

- Savidge, J., Woodford, M. & Croze, H. (1976). Report on a Mission to Zaïre, April 1976. FAO W/K 1593, 34 pp.

- Thorsell, J. (1985). World Heritage report, 1984. Parks 10: 8-9.

- UNESCO World Heritage Committee (1996) Report on the 19th Session of the World Heritage Committee,1995, Mexico.

- UNESCO World Heritage Committee (2000) Report on the 23rd Session of the World Heritage Committee,1999. Paris.

- UNESCO World Heritage Committee (2001) Report on the 24th Session of the World Heritage Committee,2000. Paris.

- UNESCO World Heritage Committee (2002) Report on the 25h Session of the World Heritage Committee,2001. Paris.

- Van den Bergh, W. (1955). Nos rhinoceros blancs. Zool. Garten 21(3): 129-151.

- Verschuren, J. (1948). Ecologie et biologie des grand mammifères (primates, carnivores, ongules). In De Saeger, H., Exploration du Parc National de la Garamba. Mission H. de Saeger (1949-1952). Institut des Parcs Nationaux du Congo Belge, Bruxelles. 225 pp.

- World Heritage Nomination submitted to UNESCO for Garamba National Park.(Includes a detailed bibliography).

- WWF (1984). The last refuge of the northern white rhino. Monthly Report, November.

- WWF (1996a) Rhino birth in Garamba. WWF News Autumn 1996.

- WWF (1996b) List of Projects Vol. 5: Africa/Madagascar Part 1. WWF, Gland, Switzerland.

| Disclaimer: This article is taken wholly from, or contains information that was originally published by, the United Nations Environment Programme-World Conservation Monitoring Center (UNEP-WCMC). Topic editors and authors for the Encyclopedia of Earth may have edited its content or added new information. The use of information from the United Nations Environment Programme-World Conservation Monitoring Center (UNEP-WCMC) should not be construed as support for or endorsement by that organization for any new information added by EoE personnel, or for any editing of the original content. |

1 Comment

Peter Howard wrote: 02-02-2011 20:08:39

Readers may want to visit the African Natural Heritage website to view a selection of images and map of the Garamba National Park world heritage site, and follow links to Google Earth and other relevant web resources: http://www.africannaturalheritage.org/Garamba-National-Park-DR-Congo.html