False killer whale

The False killer whale (Pseudorca crassidens) is the fourth largest member of the family delphinidae (Oceanic Dolphins), the largest being its close relative: the Killer whale. Contrary to widespread belief, the False killer whale is actually a dolphin among the order cetaceans. Interestingly, this dolphin will skin its prey with its teeth before consuming the fish.

The false killer whale's apparently playful nature and fast, acrobatic swimming mean that individuals are frequently encountered skilfully surfing the bow waves of sea vessels, porpoising or leaping clear of the water surface. This rapid locomotion also makes the false killer whale a highly-efficient predator, and it feeds on an array of different prey items, which, depending on its location, may include: salmon, squid, tuna and mahi mahi. Groups of false killer whales have also been observed feeding on smaller dolphins and even attacking humpback and sperm whales. A highly social species, the false killer whale usually forms groups, or pods, of between 10 and 50 individuals of mixed sex and age, but these may occasionally merge into superpods of over 800 animals. Pods appear to communicate extensively by producing an incredibly diverse array of clicks and whistles. Sound is also employed by the animals in the form of echolocation, which is used to sense their environment and locate prey. Breeding is believed to occur throughout the year, but may peak at different times depending on the location. After a gestation period of about 15.5 months, the calves are born measuring up to two metres in length and for the first 18 to 24 months are fed on milk. The females reach sexual maturity at 8 to 11 years and are estimated live for up to 62 years, while the males may only reach maturity at 16 to 18 years and live for around 57 years.

Contents

Physical description

False killer whales are black or dark gray with a white blaze on their ventral side. Some have a paler gray coloring on their head and sides. Their heads are rounded with a melon-shaped forehead. Their bodies are elongated. The dorsal fin is sickle-shaped and protrudes from the middle of their back, the pectoral flippers are pointed. They have a slight overbite--the upper jaw extends beyond giving them a beak-like appearance.

Adult males range from 3.7 to 6.1 metres in length, while adult females range from 3.5 to 5 m. Adults may weigh 917 to 1842 kg. Newborns range from 1.5 to 1.9 m in length and weigh about 80 kg.

This species has a more slender build compared to other dolphins and they have tapering heads and flippers. Their flippers average about one-tenth of the head and body length and have a distinct hump on the leading margin of the fin. There is a definite median notch on their flukes and they are very thin with pointed tips.

This species is often mistaken for the bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops truncatus), the short-finned pilot whale (Globicephala macrorhynchus), or the long-finned pilot whale (Globicephala melas) as they inhabit the same regions. To distinguish these species, bottlenose dolphins have beaks, and pilot whales are larger with obvious dorsal fin differences.

Reproduction

Although false killer whales breed year-round, their breeding peaks in late winter to early spring. Studies suggest they are polygynandrous.

False killer whales will only have one calf per pregnancy and she carries that calf for 11.0 to 15.5 months. The calf stays with the mother for 18 to 24 months. Between 18 and 24 months old, the calf is gradually weaned. Sexual maturity occurs in females between 8 and 11 years of age and in males at 8 to 10 years.

In this species and a few others in the family delphinidae, if the female does not conceive after the first ovulation, she will continue ovulating until she does conceive. After giving birth, the female will not breed again for an average of 6.9 years.

After a False killer whales calves are born, each juvennile is cared for and nursed by its mother for up to 24 months. Young are capable of swimming on their own shortly after birth. Young are likely to remain in the same social group with their mother beyond weaning.

Lifespan

Researchers estimate that males live an average of 57.5 years and females live an average of 62.5 years in the wild. No known age-dependent mortality rate has been discovered. Because few False killer whales are kept in captivity, captive lifespans are unknown.

Behavior

False killer whales are found in groups ranging from just a few individuals to hundreds of individuals. In these large groups they are sometimes separated into smaller groups or pods, which average about 18 members (typically 10 to 30). Pods consist of all ages and both sexes.

False killer whales often "strand" themselves in large numbers. Large strandings have been reported on beaches in Scotland, Ceylon, Zanzibar and along the coasts of Britain. It is thought that some groups might have been chasing groups of seals or sea lions into the shallower waters and became stranded.

They prefer faster-moving ships, but will ride the bow waves on any vessel. They are one of the few large mammals that leap out of the water over the wake of the ship, which is a useful identification attribute. It has been said that false killer whales are as social as the pilot whale (Globicephala).

Pseudorca crassidensuse echolocation and like otherOdontocetialso use other sounds, such as whistles, squeals, or less distinct pulsating sounds.

Distribution

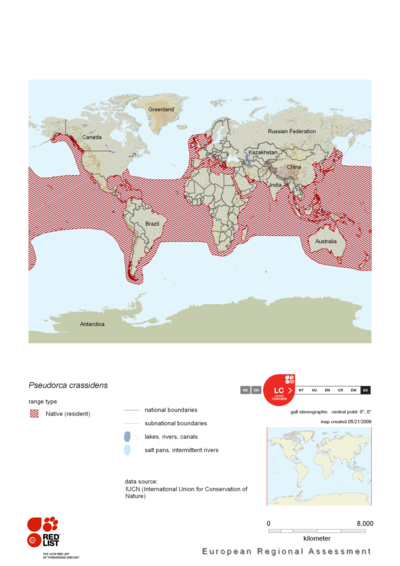

False Killer Whale Distribution in the World. Source: IUCN

False Killer Whale Distribution in the World. Source: IUCN

Pseudorca crassidensis found throughout the Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian Oceans. It is nearly cosmopolitan, occurring at latitudes as far north as 50 degrees north and as far south as 52 degrees southern latitude.

Habitat

False killer whales are common in tropical or temperate seas. They visit coastal waters but prefer to remain in deeper waters. They are known to dive as deep as 2000 meters.

Ecosystem roles

This cetacean are known to associate with the Pilot whale. False killer whales are predators of fish and squid (Loligo duvaucelii), and they also eat smallerDelphinidaeand pinnipeds (e.g., seals [[class="taxon">Phocidae]], and sea lions [[class="taxon">Otariidae]]). One protozoan that is found in false killer whales is the parasite Bolbosoma capitatum. The False killer whale is also a carrier of two types of whale lice:Lsocyamus delphini andCyamus antarcticensis.

Feeding habits

False killer whales are carnivores, eating primarily fish and squid. They mainly eat squid (Loligo) but also opportunistically take fish and occasional marine mammals, such as seals ([class="taxon">Phocidae]) or sea lions ([class="taxon">Otariidae]). Some of the fish they eat include salmon (Oncorhynchus),SciaenidaeandCarangidaefishes, bonito (Sarda lineolata), mahi mahi (Coryphaena hippurus), yellowfin tuna (Thunnus albacares), yellowtail (Pseudosciana manchurica), and perch (Lateolabrax japonicus). On one occasion researchers found the remains of a humpback whaleMegaptera noveangliaein the stomach of a false killer whale.

This species moves swiftly in order to catch fish prey. This cetacean has been observed snatching a fish by mouth while completely breaching the water surface. They have also been seen shaking their prey until the head and entrails are shaken apart. The dolphin will then peel the fish using its teeth and discard the entire prey skin before eating the remains. Some mothers will hold a fish in the mouth, allowing the calf to feed on the fish, although this food manipulation is rarely observed in Cetacea in general.

Conservation status

Although false killer whales are hunted by humans and there are annual mass strandings, populations are considered stable. There are only a few countries that hunt them for food or remove them as threats to the fisheries industry. The IUCN Red List considers the species to be data deficient as far as conservation classification.

Threats

Owing to this species believed impacts on fisheries, humans choose to kill false killer whales in significant numbers. In some regions in the eastern tropical Pacific Ocean, they are also hunted for meat.

References and further reading

- IUCN Red List

- Cynthia Parr. 2010. False killer whale. Encyclopedia of Life

- Nowak, R.M. (1999) Walker's Mammals of the World: Volume 2. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, Maryland

- CITES (December, 2008)

- Baird, R.W. (2002) False Killer Whale. In: Perrin, W.F., Wursig, B. and Thewissen, J.G.M. Eds. Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals. Academic Press, London.

- Convention on Migratory Species (December, 2008)

- Carwardine, M., Hoyt, E., Fordyce, R.E. and Gill, P. (1998) Whales and Dolphins. Harper Collins Publishers, London.

- Martin, A.R. (1990) Whales and Dolphins. Salamander Books Ltd, London.

- Parsons, E.C.M., Dolman, S.J., Wright, A.J., Rose, N.A. and Burns, W.C.G. (2008) Navy sonar and cetaceans: Just how much does the gun need to smoke before we act?. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 56: 1248 - 1257.

- Bruyns, W.F.J.M., (1971). Field guide of whales and dolphins. Amsterdam: Publishing Company Tors.

- Fletcher, N. & Curtis, D. (1999). Cetacean monitoring in the English Channel and Bay of Biscay, from platform of opportunity, over six years period (1993-1998) European Research on Cetaceans, 13, 210

- Howson, C.M. & Picton, B.E. (ed.), (1997). The species directory of the marine fauna and flora of the British Isles and surrounding seas. Belfast: Ulster Museum. Museum publication, no. 276.

- Jefferson, T.A., Leatherwood, S. & Webber, M.A., (1994). FAO species identification guide. Marine mammals of the world. Rome: United Nations Environment Programme, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

- Kinze, C. C., (2002). Photographic Guide to the Marine Mammals of the North Atlantic. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Reid. J.B., Evans. P.G.H., Northridge. S.P. (ed.), (2003). Atlas of Cetacean Distribution in North-west European Waters. Peterborough: Joint Nature Conservation Committee.

- Banks, R. C., R. W. McDiarmid, A. L. Gardner, and W. C. Starnes. 2003. Checklist of Vertebrates of the United States, the U.S. Territories, and Canada

- Banks, R. C., R. W. McDiarmid, and A. L. Gardner. 1987. Checklist of Vertebrates of the United States, the U.S. Territories, and Canada. Resource Publication, no. 166. 79

- Borges, P.A.V., Costa, A., Cunha, R., Gabriel, R., Gonçalves, V., Martins, A.F., Melo, I., Parente, M., Raposeiro, P., Rodrigues, P., Santos, R.S., Silva, L., Vieira, P. & Vieira, V. (Eds.) (2010). A list of the terrestrial and marine biota from the Azores. Princípia, Oeiras, 432 pp.

- Convention of Migratory Species. Review on Small Cetaceans: Distribution, Behaviour, Migration and Threats. None. Germany: Boris Michael Culik, Marco Barbieri. 2005. Accessed September 20, 2007.

- Felder, D.L. and D.K. Camp (eds.), Gulf of Mexico–Origins, Waters, and Biota. Biodiversity. Texas A&M Press, College Station, Texas.

- Gordon, D. (Ed.) (2009). New Zealand Inventory of Biodiversity. Volume One: Kingdom Animalia. 584 pp

- IUCN (2008) Cetacean update of the 2008 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.

- Jefferson, T.A., S. Leatherwood and M.A. Webber. 1993. Marine mammals of the world. FAO Species Identification Guide. Rome. 312 p.

- Koukouras, Athanasios (2010). check-list of marine species from Greece. Aristotle University of Thessaloniki. Assembled in the framework of the EU FP7 PESI project.

- Liebig, P., K. Flessa, T. Taylor. 2007. Taphonomic Variation Despite Catastrophic Mortality: Analysis of a Mass Stranding of False Killer Whales(Pseudorca crassidens), Gulf of California, Mexico. Palaios, Volume 22, Issue 4: 384-391.

- MEDIN (2011). UK checklist of marine species derived from the applications Marine Recorder and UNICORN, version 1.0.

- Mead, James G., and Robert L. Brownell, Jr. / Wilson, Don E., and DeeAnn M. Reeder, eds. 2005. Order Cetacea. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference, 3rd ed., vol. 1. 723-743

- Minasian, S., K. Balcomb, III, L. Foster. 1984. The World's Whales. New York and London: W.W. Norton & Company.

- North-West Atlantic Ocean species (NWARMS)

- Nowak, R. 1999. Walker's Mammals of the World. Baltimore and London: The John Hopkins University Press.

- Owen, R.A., 1846. A history of British fossil mammals and birds, p. 516. London, 560 pp.

- Perrin, W. (2011). Pseudorca crassidens (Owen, 1846). In: Perrin, W.F. World Cetacea Database. Accessed through: Perrin, W.F. World Cetacea Database at http://www.marinespecies.org/cetacea/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=137104 on 2011-02-05

- Perrin, W., B. Würsig, J. Thewissen. 2002. Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals. United States of America: Academic Press.

- Ramos, M. (ed.). 2010. IBERFAUNA. The Iberian Fauna Databank

- Rice, Dale W. 1998. Marine Mammals of the World: Systematics and Distribution. Special Publications of the Society for Marine Mammals, no. 4. ix + 231

- Richard Weigl (2005) Longevity of Mammals in Captivity; from the Living Collections of the World. Kleine Senckenberg-Reihe 48: Stuttgart.

- Shirai, K., T. Saki. 1997. Haematological Findings in Captive Dolphins and Whales. Australian Veterinary Journal, 75/7: 512-514. Accessed October 18, 2007.

- Shirihai, H., B. Jarrett. 2006. Whales, Dolphins and Other Marine Mammals of the World. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press.

- Slijper, E. 1962. Whales. New York: Basic Books Inc..

- Stacey, P., S. Leatherwood, R. Baird. 1994. Pseudorca crassidens. Mammalian Species, 456: 1-6.

- Stacey, Pam J., Stephen Leatherwood, and Robin W. Baird. 1994. Pseudorca crassidens. Mammalian Species, no. 456. 1-6

- UNESCO-IOC Register of Marine Organisms

- Watson, L. 1981. Sea Guide To Whales of the World. New York, NY: Elsevier-Duton Publishing Co Inc

- Wilson, Don E., and DeeAnn M. Reeder, eds. 1993. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference, 2nd ed., 3rd printing. xviii + 1207

- Wilson, Don E., and F. Russell Cole. 2000. Common Names of Mammals of the World. xiv + 204

- Wilson, Don E., and Sue Ruff, eds. 1999. The Smithsonian Book of North American Mammals. xxv + 750

- van der Land, J. (2001). Tetrapoda, in: Costello, M.J. et al. (Ed.) (2001). European register of marine species: a check-list of the marine species in Europe and a bibliography of guides to their identification. Collection Patrimoines Naturels, 50: pp. 375-376