Exploration of the Antarctic in the Second Half of the Nineteenth Century

Exploration of the Antarctic - Part 5

See also Chronology of Antarctic Exploration.

Following the three national expeditions to the Antarctic in 1838-42, by France, the United States and Great Britain, Antarctic exploration slowed considerably for the remainder of the nineteenth century. There were several reasons for this. First, national prestige and glory looked north with the continued search for a Northwest Passage from the Atlantic to the Pacific. When British arctic explorer John Franklin—commanding the two ships used by James Ross in the Antarctic—disappeared entirely in the Canadian Arctic (1845-8), polar explorers focused numerous attempts to find the remains of the lost expedition.

Second, commercial interest from sealers was never sustained because of the repeated rapid decimation of newly discovered populations of seals. This prevented any sustainable industry being established in southern waters. After the discovery of Heard Island in 1853 there was a rush to harvest its elephant seals until they were on the brink of extinction. The whaling industry was focused on the Right Whale in northern waters and would not turn to [[Antarctic]a] until the 1890.Interest in Antarctic seemed to become a matter of loose ends and side shows.

One loose end was the extent of magnetic measurements taken by the Ross expedition, which did not reach the Southern Ocean below the Ocean]. In 1845, a British expedition led by Thomas Moore in the ship Pagoda sailed to this region and fill in the gaps in the data. A side note was that the expedition set a record for distance traveled inside the Antarctic Circle—but did not chart any additional land.

One side show was a visit from the British navy steamship, HMS Challenger, which was on a four-year global oceanographic expedition. On February 16, 1874, it became the first steam powered ship to enter the Antarctic Circle. HMS Challenger it did not chart new land, but did dredge the ocean floor, discovering granite, quartz, limestone, and sandstone that could not have come from the volcanic islands of the Southern Ocean. The quantity of these rocks increased as the expedition moved south suggesting that icebergs were carrying the rocks from a continent further south. Further evidence of [[Antarctic]a]'s existence.

Among the Challenger's scientists was a pioneer of modern oceanography John Murray. Following the expedition, Murray took a leading role in the twenty-year effort of editing and publishing the results that ran to over 50 volumes. At the conclusion, Murray would make pointed calls for a new era of Antarctic exploration.During this period, a steam-powered German whaler, Gronland, unsuccessfully searched for new whaling grounds in the Weddell Sea—the Right Whales by the Ross expedition had reported Right Whales in the area. In the course of its search, the Gronland explored and charted parts of the Antarctic Peninsula including Bismark Strait and Wilhelm Archipelago.

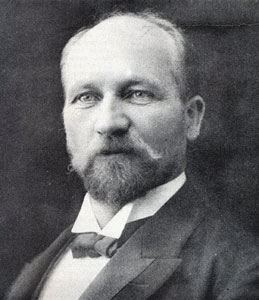

In the 1890s, declines in Arctic whale populations renewed Antarctic interest from whalers to repeat the Gronland's effort. Two whaling expeditions tried during the 1892-3 summer season. Commercially, neither expedition was successful. The Dundee Whaling Expedition identified Dundee Island as separate from Joinville Island (discovered by Dumont d'Urville)) at the norther tip of the Antarctic Peninsula. A Norwegian expedition led by Carl Anton Larsen explored the east side of the Antarctic Peninsula.

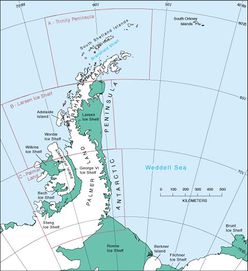

Larsen collected fossils which gained attention and had a more significant impact on thinking that the earlier find of James Eights. It was now clear that Antarctic was not always covered in ice with few species of flora and fauna. The fact that the fossils were embedded in sedimentary rocks also increased the likelihood that [[Antarctic]a] was indeed a continent.Undeterred by the commercial failure of the first outing, Larsen returned to Antarctic in the following season (1993-4), and sailed along the edge of a vast ice wall on the east coast of the Antarctic Peninsula, now known as the Larsen Ice Shelf. (Larsen even explored the ice on skis; another first.) Larsen also discovered Oscar II Coast, Foyn Coast as well as various mountains. Right Whales were not found but Larsen successfully hunted the recovering seal populations.

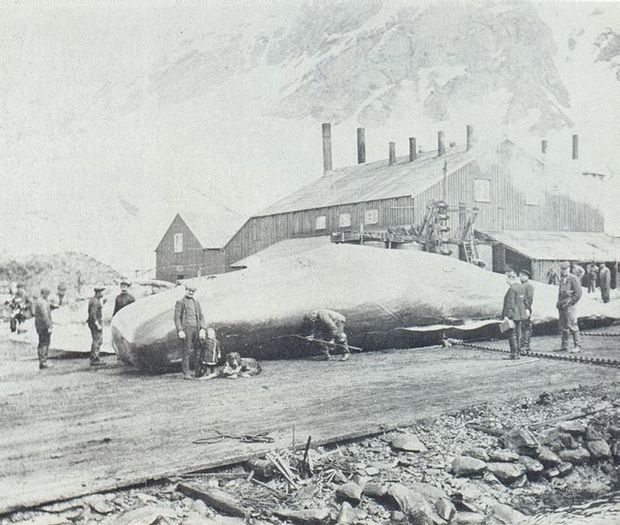

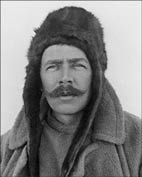

More significant was the recognition by Larsen that new technologies (particularly the recently invented grenade harpoon gun) would allow hunting of the more difficult but more common rorqual whales (Blue, Fin, Humpback, Sei and Minke Whales) in the Southern Ocean. In 1904, Larsen established a whaling base at Grytviken on South Georgia Island which launched the Antarctic Whaling Industry. Also, Larsen would play an important role in the Swedish Antarctic Expedition (1901-04) where his ship was trapped and crushed by pack ice (see The "Heroic Age" of Antarctic Exploration). Another Norwegian whaling expedition, led by Henryk Bull following up of Ross's reports of Right Whales in the Ross Sea, put six men, including Bull and Carsten Borchgrevink, ashore at Cape Adare, a peninsula in Victoria Land on the edge of the Ross Sea. Samples of rocks and lichens were collected. Because the 1821 landing by U.S. sealers at Hughes Bay was unknown at the the time, Borchgrevink's party were believed to be first people to stand on the continent itself.[[Antarctic Minkie Whale|]]As the end of the nineteen century drew to a close, humanity had—at best—a very general outline of the Antarctic coast; a handful of lines indicating land and an assumption that they connected in some manner. There was a little knowledge about marine life and about weather. There was no knowledge about the interior. Moreover, there was growing scientific interest in polar regions for various reasons,

From 1881-3, was the First International Polar Year (international scientific initiatives frequently use the word "year" very loosely) inspired by the Austrian explorer Carl Weyprecht and focus strongly on meteorology and geophysics in the Arctic. In 1893, John Murray made an influential speech on "The Renewal of Antarctic Exploration" to the Royal Geographical Society in which he reviewed the poor state of knowledge of [[Antarctic]a] and the many scientific questions that ought to be answered by future expeditions.

Six months after the landing at Cape Adare by Norwegian whalers, the Sixth International Geographical Congress met in London (July 1895) and, influenced strongly by Murray, proclaimed that:

". . . exploration of the [[Antarctic] Regions] is the greatest piece of geographical exploration still to be undertaken. That in view of the additions to knowledge in almost every branch of science which would result from such a scientific exploration the Congress recommends that the scientific societies throughout the world should urge in whatever way seems to them most effective, that this work should be undertaken before the close of the century."

Appropriately, this statement would usher in a new era of Antarctic exploration and what would become known as the "Heroic Age" of Antarctic exploration.

Further Reading:

- Exploring Polar Frontiers: An Historical Encyclopedia, William James Mills, ABC-CLIO, 2003 ISBN: 1576074226.

- The Race to the White Continent, Alan Gurney, W.W. Norton and Company, 2002 ISBN: 0393323218.

- Index to Antarctic Expeditions, Scott Polar Research Institute, retrieved November 1, 2008

- The Renewal of Antarctic Exploration, J. Murray, Geographical Journal, vol. 3, pp. 1–3, 1894

- Antarctic History, Polar Conservation Organization, retrievedFebruary 16, 2009

- Antarctic History, Antarctica Online, retrieved February 16, 2009

- The Antarctic Circle,retrieved February 16, 2009