Cooperative Climate: Chapter 6

Contents

- 1 The Fund Proposal

- 2 Notes This is a chapter from Cooperative Climate: Energy Efficiency Action in East Asia (e-book). Previous: Part III. Proposal for a New Energy Efficiency Policy Development Fund (Cooperative Climate: Chapter 6) |Table of Contents (Cooperative Climate: Chapter 6)|Next: A Final Word from Co-editor Taishi Sugiyama

The Fund Proposal

The findings in the last two pages lead us to propose establishing the Policy Development Fund for East Asian Energy Efficiency Cooperation (henceforth, the “Policy Development Fund” or the “Fund”), which is a new, dedicated fund for energy efficiency policy development cooperation in East Asia. This chapter discusses the key design issues of the Fund, presents the Fund proposal in a legal format and assesses its political feasibility and effectiveness.

6.1 Key Design Issues

A. Requirements of the Fund

There are many requirements that the Fund proposal, or any institutional design proposal in general, has to meet in order to attract enough political attention and support so that the institution will be politically stable over the long run. In addition to the lessons summarized in the previous pages, the following will have to be taken into consideration:

a) Careful consideration of national priorities and sensitivity to participating countries

National priorities differ across countries. Most countries attach a high priority to economic efficiency and energy security, and are keen on international cooperation. However, some countries’ attitudes are not welcoming—sometimes even adversarial—when the issue is framed as emissions control in the context of climate change. Furthermore, we have to note that national circumstances are rapidly changing in this fast-growing region. A policy that was successful 10 years ago may be outdated today.

b) Aim for massive energy savings and significant emissions reductions

Working on a single project at a specific site does not necessarily result in a significant impact on the energy efficiency of a country as a whole. We have to aim at massive energy savings, with limited financial resources. For this purpose, well-focused assistance that creates appropriate incentives for the private sector will be crucial.

c) Commitment to policy mechanisms for concrete actions

While there is consensus at a general conceptual level that cooperation on energy efficiency is a good idea, we must be aware that such discussions often take place without a clear idea of concrete actions. The details matter for any cooperation activity. Without careful design of concrete actions, conceptual conversations do not achieve the desired results.

d) Build upon existing activities

Launching new actions out of thin air is extremely difficult. It takes time to understand the problem, to network with local and international partners, to learn from successes and errors, and to identify a promising cooperative solution. Therefore, it is important to take advantage of existing activities when we design further concrete actions. Having given a general overview, we will go into more detail. Here we discuss key institutional design issues about the Policy Development Fund at three levels: the political agreement; modality; and coverage of the projects.

B. Political agreement

There are many ways of reaching political agreement for the Fund. We will consider the following questions: which countries join?; how many members will there be?; and what will the scope of the Fund be?

Let us first consider the number of countries. There are some issues to be considered. If it is bilateral, a political agreement might be damaged by political changes within participating countries. For example, imagine a China-Japan bilateral energy efficiency framework. A political upheaval, which has nothing to do with energy efficiency, might be an barrier to continued development of the energy efficiency cooperation.

If the Fund is joined by many countries, a bilateral upheaval does not undermine the regime and there will be less danger that the program may be captured by narrow interests. However, there are costs, too. The effectiveness of the process will be very hard to maintain if everything is discussed by all countries. For example, the CDM under the Kyoto Protocol (Kyoto Protocol to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (full text)) is struggling with the challenge of coordinating more than 180 countries.

A notable benefit of keeping the number of countries small is to make it easy to identify the areas of agreement, promote stability and align interests. This is particularly important for East Asia, since its countries are diverse, and the level of political and economic integration is not high compared to the countries within, for example, Europe or North America. Yet, interestingly enough, energy efficiency is the area where these countries can truly cooperate. They have common characteristics. Access to energy is fragile, so they are interested in energy security. They are growing economies, with strong governmental interest in improving efficiency in all economic arenas. They are trading energy equipment within the region and exporting to the rest of the world. Having a common agenda with strong economic interaction within the region is an important background for mobilizing financial and human resources, and sustaining the political interest of participating countries.

With these considerations, the authors believe that the countries should start with a multilateral agreement from the outset to avoid the potential weaknesses of bilateral arrangements, but keep the number of initial participants small (perhaps as many as six) and then grow gradually. In the long run, the agreement might expand to include more countries. For example, it can start with Japan, Korea, China and a couple of ASEAN countries, and expand to include most of the ASEAN countries and some donors from developed countries. However, it would not be wise to envision developing countries from all over the world joining the Fund, as this would dilute the attention given to any particular country while introducing many more differences in circumstances and points of view, as well as augmenting administrative costs considerably.

As for issue area coverage, it should be confined to energy efficiency alone so that participating countries have a true area of common focus. Putting energy efficiency cooperation in the context of general energy policy may sound attractive to some policy-makers, but we have to recognize that some energy issues are very divisive. Renewable energy, energy security and climate change are issues that might turn some countries away. Renewable energy is a common goal, but not the priority for energy policy in many countries. Energy security is divisive when countries begin discussing the ownership of natural gas fields and territories in the East China Sea (East China Sea large marine ecosystem) or access to Russian oil and gas resources. Climate change is divisive when countries begin talking about a binding cap for national emissions. When combined with these issues, energy efficiency would be seen as a low priority, crippled by the adversarial negotiating climate of the other policy spheres. ASEAN+3 regimes have failed to address energy efficiency so far because oil reserves and other issues were seen as higher priorities. The CDM has a problem with its stability because the binding cap regime of the Kyoto Protocol (Kyoto Protocol to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (full text)) is divisive, and there is doubt as to whether it can be sustained after 2012.

C. Modality of the Fund

There are three questions to be answered regarding the modality of the Fund. Should it be a new fund or a branch of an existing organization? What does it fund? How does it operate?

i) New fund or branch of existing organization?

The Fund can be either a new one independent of the existing organizations (ADB, ASEAN or any other bilateral or multilateral agency), or another branch of such a new independent organization. The benefit of the latter is that the Fund could take advantage of a well-established institutional infrastructure.

The downside of having the Fund be a branch of an existing funding organization is the risk of being caught up in the bureaucracies of others. Some stakeholders interviewed expressed concern about the amounts of paperwork and lead-time required by some existing organizations. The burden of paperwork is serious since the office in charge of energy efficiency is often understaffed. Lead-time—months to years for an idea to be implemented—is also critical because the terms of governmental positions are often as short as two years, and because capturing political timing, such as political debates due to an energy price spike, is also important for implementing energy efficiency policy. A new and independent office could set up its own systems and infrastructure and could conceivably be as nimble and responsive to recipients as it wanted to be.

While international banks and organizations are aware of such requests and are struggling for improvement, there is a limit to how much change is feasible. These organizations were established for other purposes. For example, part of the mandate of a multilateral development bank is to advance sustainable development through full accountability and transparency. Given this mandate, all their activities should naturally go through the required paperwork to show how it contributes to sustainable development.

However, perhaps such processes are unnecessary for the implementation of most energy efficiency improvement, especially with the limited amount of money in question. If a bank supports energy efficiency, it is obvious that it contributes to sustainable development. If the target is policy development, the money at stake is not as high as the multilateral development bank’s contribution to an infrastructure-development project. Of course, the funding has to be cost-effective; the project should not result in adverse impacts to ecosystems and people; and the Fund should be accountable to donors. Still, given the much narrower and simpler scope for a Policy Development Fund, it can have a much simpler, more cost-effective governance system.

Given the above, the authors believe there is a need for a new and dedicated fund, independent of existing multilateral organizations, that will be used by policymakers in developing countries who specifically want to develop quick energy efficiency policies. Having a new and dedicated fund will also send a strong signal of political recognition for energy efficiency and will consider the dynamic needs of developing countries in the region as they change rapidly.

ii) What does it fund?

The targets are co-financing of established activities as well as finding and funding new projects. Of course, finding new projects is necessary to cover a broader range of activities. However, starting everything from scratch is time consuming and counter-productive. Existing activities on policy development assistance have worked well, as described in previous chapters and as will be described in section 6.2. Many projects have been identified and funded, people have gained experience, and have established networks among key people. Unfortunately, these activities were mostly the result of personal efforts and non-profit work, and lacked stable and strong national support from countries. If the Fund refuels these activities hand-in-hand with other financial organizations, the cost effectiveness will be high.

iii) How does it operate?

The characterization of the Fund discussed above requires a quick decision-making process with little bureaucracy. At the same time, there should be accountability to the donors and the operation of the Fund should be insulated from short-term political changes. Given these considerations, the authors propose an independent, professional management structure in which a sole CEO is selected by the Executive Board (consisting of donors and recipient countries) for a term of five years.

Cost-effectiveness, in terms of the amount of foreign assistance versus energy savings in recipient countries, should be the key criterion in the selection of projects. However, we should allow the Fund to undertake strategic, long-term projects, such as establishing information platforms as well as short-term ones in order to nurture opportunities for long-term, massive energy cuts.

D. Project Coverage of the Fund

The Fund’s potential target technologies and sectors are numerous given the broad definition of the Fund—policy development for energy efficiency. Given that almost all sectors in developing countries need further policy development—including information gathering; law stipulation; standard setting; monitoring; enforcement; and revision—there is a lengthy list of potential areas of cooperation. Table 6.1 illustrates the scope of activities, technologies and sectors to be addressed. To cover this range, the Fund has to have a professional operational system well-linked with a cross-border expert network that appropriately identifies key areas and captures ripe opportunities within individual developing countries.

|

Table 6.1. Indicative list of target sectors under the Policy Development Fund. |

|

Building Sector

|

|

Industrial Sector

|

|

Transportation Sector

|

|

Cross-cutting

|

| Note: The details are given in section 6.2 (B) for projects in italics |

6.2 The Policy Development Fund

Following the consideration of the key design issues above, we summarize our proposal in legal format to clarify the points, and then follow up with an assessment of the Fund’s political feasibility and effectiveness.

A. The Fund Proposal

The concept of the Fund is summarized as follows.

- The Fund. Like-minded countries in East Asia agree to establish “The Policy Development Fund for East Asian Energy Efficiency” (hereafter referred to as “the Fund”).

- Aim of the Fund. The Fund aims to promote energy efficiency through financial assistance for implementing policy and measures in the member countries.

- Contribution to the Fund. Governments and private organizations voluntarily contribute to the Fund.

- Relationships with relevant preceding activities. The Fund implements its programs either independently or through existing international networks and other organizations, whichever are deemed appropriate.

- Target region. The Fund will start with a membership of three to six countries, with a goal of including most of the following: Japan, Korea, China and the ASEAN region.

- Measure of the Fund activity. Activities of the Fund shall be measured in terms of both actions and outcomes. For example, the following indicators are used for the appliance/automobile energy efficiency policy: on the action side, stipulation/revision of standards and labels; on the outcome side, the estimated energy and emissions cut.

- Institutional structure. An Executive Board and a Secretariat are established for the Fund. The Secretariat is led by a CEO designated by the Executive Board.

- Modality of the Executive Board. One seat for each member country. Voting rules are weighted by contributions to the Fund. A Chair is selected by the Executive Board.

- Modality of the work of CEO. The Fund is managed by the CEO. The CEO is accountable to the Executive Board. The CEO is not necessarily from any of the member countries. The CEO is responsible for allocating funds to programs proposed by the member countries or other organizations. The CEO is required to consider the following criteria upon selecting the programs: cost-effectiveness; measurability of the actions; and outcomes. The CEO has a term of five years.

- Modality of the work of the Secretariat. The Secretariat is hired by, and works for, the CEO.

- Relationships with the Sovereignty. The Fund does not impose specific policies in the member countries. It is a member country’s prerogative to decide the style and stringency of their own laws, standards and any other governmental actions.

- Scope of the Fund’s activities:

a) General:

- The Fund is available for the development and initial implementation of policy, not for the continuing costs incurred by the policy itself.

- The Fund focuses on measurable and cost-effective activities.

b) Examples of policies, equipment/facilities:

- Development/monitoring of efficiency standards and labels for appliances (e.g., light bulbs, air conditioners, copy machines, etc.) and automobiles.

- Development of voluntary actions in industrial sectors/facilities

- Development/monitoring of tax incentives and subsidy policies

- Others.

- (For a more detailed list, see Table 6.1).

13. Relationship with the UNFCCC/Kyoto Protocol (Kyoto Protocol to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (full text)). The Fund is independent of the UNFCCC/Kyoto Protocol but aims to be part of global action to mitigate climate change.

14. Revision of the modality. The Executive Board may revise the modality (1 through 13) of the Fund.

We add some remarks to clarify the modality of the Fund. Financial contributions by donors are voluntary. Regarding the order of magnitude of the Fund, we think it is politically feasible in donor countries to secure US$10–30 million annually at its initial stage, a modest amount compared to other international commercial and official financial activities.[1] It may expand further once the Fund proves to be operational and useful.

Financial support by the Fund is dedicated to formulation and initial implementation of energy efficiency policies in member countries. Recipients commit to implementation by themselves. Recipients, not donors, retain discretion over types and stringency of policy measures. It is important to maintain the voluntary nature of the Fund, otherwise it will be difficult to secure commitments by countries at the outset.

The CEO makes key operational decisions, including project selection, under the guidance of the Executive Board. While cost-effectiveness serves as the major criterion for the selection, a limited share is allocated to long-term strategic projects. The Fund supports new projects as well as existing efforts through co-financing.

It is important to measure the activities of the Fund by actions (e.g., laws stipulated, compliance monitored in the market, institutions established, etc.) as well as outcomes (e.g., energy savings and emission reductions). If the focus is solely on actions, there is a danger that the activities will be ill-designed, conducted irresponsibly and may have only a minimal impact. If the focus is too much on the outcomes, there is a danger that the scope of the projects will be limited to a narrow scope and the cost-effectiveness will be lost through high transaction costs. In the CDM, it is mandatory to rigorously calculate the emissions cut, because the certified emissions reductions (CERs) are to be traded with other emission units under the Kyoto Mechanisms, which translates into fewer emission cuts required for the developed countries domestically. The requirement for rigor is one of the reasons why the scope of CDM has been limited so far to methane, HFC and other non-energy greenhouse gas projects for which it is easier to agree upon quantification, and only a small part of the energy efficiency potential is likely to be explored through the CDM. Methodologically, it is very difficult to have an “accurate” estimate for the outcome of any project. The error range for an estimated emissions cut by a project can be as large as 50 per cent or more because there are data limitations, and the estimates are against a counterfactual baseline (emissions that would occur otherwise) that is largely subjective. For policy development assistance, the amount of emissions at stake as well as the likely range of error tend to be even larger than a project in a specific site with a specific technology. Putting too much emphasis on the rigor of the estimate could result in missing the most promising mode of energy efficiency improvement assistance.

B. Example projects

In order to illustrate how projects might operate under the Fund, four examples are provided below: (i) appliance S&L (e.g., CLASP); (ii) automobile fuel economy; (iii) efficient (low-resistance) tires; and (iv) voluntary efficiency agreements in industry. Each example includes: (a) background; (b) an explanation of what the Fund would pay for; and (c) a description of the potential energy savings and carbon reductions where data are available.

While these examples would help the readers have a better understanding about the policy development assistance, these four are by no means exhaustive. They are chosen (1) on the basis of the availability of data to the authors; and (2) to cover the building (residential and commercial) sector and the transport sector—for which energy consumption is rising most rapidly—as well as industry, which still consumes a large share of energy.

i) Appliance Standards & Labeling (CLASP)

a) Background

Most East Asian countries, including China and Japan, have ongoing S&L programs as we have reviewed in Chapter 2 (Cooperative Climate: Chapter 6). Japan’s Top Runner program is recognized throughout the world for its innovation and effectiveness. China’s program includes MEPS, comparison labels and endorsement labels. As mentioned in Part II, S&L programs require continuous refinement of product testing protocols; ratcheting of standards to more stringent levels; application of standards and labels to more energy-consuming products; strengthening enforcement procedures; and otherwise fine-tuning the S&L program to achieve greater and more cost-effective energy savings and GHG reductions.

b) What the Fund would pay for

Here is one example of how the Fund might support China’s S&L program. The Fund might engage CLASP to conduct an assessment of the best practices in the enforcement of MEPS among the 49 countries that have adopted them. It might hold a workshop to explore the applicability of alternative enforcement mechanisms to China. And it might provide funding to the appropriate Chinese agencies to refine China’s enforcement procedures, with or without additional outside assistance. Such opportunities exist throughout all the six essential steps of standard-setting and labeling:

- developing a testing capability

- designing and implementing a label program

- analyzing and setting standards

- designing and implementing a communications program

- ensuring program integrity

- evaluating the S&L program.

Throughout China’s design and implementation of its S&L program, CLASP has provided technical assistance in a variety of its aspects, ranging from providing the methodology for setting standards levels and labeling criteria, to drafting proposals for GEF co-funding. CLASP remains available to continue with such assistance.

c) Energy implications

As mentioned earlier, S&L is one of the most effective policies a government can adopt as a means of fostering economic development and reducing carbon dioxide [[emission]s]. For each taxpayer dollar it spends on S&L, the U.S. government has generated $400 in net economic benefit to the economy and reduced four tons of carbon dioxide emissions over product lifetimes at a government cost of $0.06 per ton. By the year 2020, experts calculate that energy efficiency standards and labeling will have helped avoid 20 per cent of planned new power generation, with the cost of saving each kilowatt being one-third of what it would have cost to generate it (Meyers, 2002).

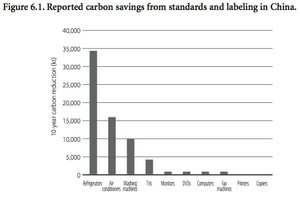

Similar potential exists for most countries, as preliminary evaluations show for Thailand, Korea, Mexico and China. An unpublished study of China’s energy efficiency standards conducted for the U.S. Energy Foundation estimated savings from eight new minimum energy performance standards and nine energy efficiency endorsement labels that were implemented from 1999 through 2004 for appliances, office equipment, and consumer electronics. The study concluded that during the first 10 years of implementation, these measures will save 85 terawatt hours (TWh) of electricity and 82 megatonnes of CO2 annually, as shown in Figure 6.1. By 2020, China’s S&L program is estimated to save 11 per cent of its residential energy use and avoid the need for US$20 billion investment in power plant construction (the equivalent of 50 units of 500MW coal-fired power plants). The potential savings from China improving and expanding its S&L program over the next few years is half again the amount already saved.

Another unpublished report estimated that the cost, in terms of the amount of foreign assistance versus CO2 emission reductions, was about US$0.20 per ton of CO2. This is much less than some organizations are currently investing for CDM credits.

ii) Automobile Fuel Economy Standards in China

a) Background

Transport energy accounts for a third of total energy consumption in most developed countries. Although per capita consumption is still low in many developing countries, it is rapidly increasing.

An important characteristic of the transport sector is that it is highly dependent on oil. Before the oil supply shock of 1973 many countries used oil in almost all sectors including transport, industry, household and power generation. Since 1973, governments have taken action to replace oil with coal, natural gas, nuclear and renewable energy. As a consequence, most sectors are not highly dependent on imported oil now, except for the transport sector. Despite intensive governmental efforts to develop alternative fuel for automobiles, including coal liquefaction, synthetic oil production from natural gas and biomass ethanol production, the automobile sector is still dependent mostly on oil.

Access to oil was one of the major sources of international conflict throughout the twentieth century and is still regarded as a strategic national interest today. Combined with scarce resource availability in East Asia, energy supply security is of utmost priority for countries in the region. In particular, Chinese dependence on imported oil is growing and expected to increase in coming years. The percentage of crude oil imported has been rising from 31 per cent in 2002, and is estimated to grow to over 50 per cent by 2007. Over the next 10–15 years, Chinese oil consumption is expected to increase four per cent per year, positioning China as the world’s second largest oil consumer behind the United States. By 2020, China is expected to become the world’s largest oil consumer, with total projected oil consumption of 27.6 million barrels a day (Energy Information Administration, 2004).

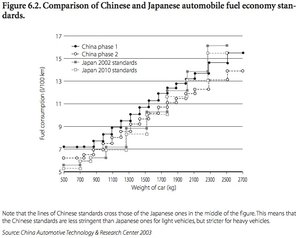

China’s Energy Conservation Act entered into force in 1998. As a part of implementation activities, China Automotive Technology and Research Center (CATRC), under the leadership of the former State Economic & Trade Commission (SETC), convened research on Chinese Automotive Fuel Economy Standards. The subsequent report made proposals for fuel economy standards in China. As a result, China announced new fuel economy standards for its passenger vehicle and fleet in December 2003. These standards are weight-based and were to be implemented in two phases. The first was in 2005–2006 and the second in 2008, with separate standards for manual and automatic transmissions. Each vehicle sold in China will be required to meet the standard for its weight class. Overall, Chinese fuel economy standards are slightly more stringent than current fuel economy regulations in the U.S. Compared to Japan, China’s standards are less stringent for light vehicles, but are much stricter for heavy vehicles including sports utility vehicles (SUVs). China’s standards for heavy vehicles may be the most stringent in the world (Figure 6.2) (China Automotive Technology and Research Center, 2003; Sauer and Wellington, 2004).

Complying with these standards will be a challenge for manufacturers. According to analysis by the World Resources Institute, some international manufacturers will have to completely change the product mix to meet the standards. As such, the Chinese standards will have enormous impact on the transformation of the Chinese automobile market. Of course, it is yet to be seen if manufacturers will comply with the standards. It is unknown to what degree the standards will be monitored and enforced by Chinese authorities, particularly for Phase II standards. This leaves uncertainty about the degree to which the standards may affect the financial performance of automakers in China (Sauer and Wellington, 2004).

It is important to note that the standards were developed with international cooperation. The U.S.-based Energy Foundation provided part of the funding for the technical work necessary to develop the regulations. Several auto companies including Toyota, Honda, General Motors and Volkswagen, among others, provided expertise regarding the technical feasibility of the standards (China Automotive Technology and Research Center, 2003). This case clearly illustrates that (1) there are strong incentives for energy conservation in key developing countries; (2) international cooperation is important for the development and initial implementation of policies in developing countries; and (3) there is no need to mention politically-divisive issues, such as ownership disputes for gas fields or climate change, in order to make progress on energy efficiency improvement.

b) What the Fund Would Pay For

The development of the standards described above sets a very important precedent. If a country is interested in developing energy efficiency policies, an international fund can support technical work. That the standards have been set at ambitious levels—in particular for heavy vehicles—is a remarkable success. Future agenda items for the Fund will include the following:

- estimate environmental and energy benefits of the fuel economy standards

- develop policies for implementation, monitoring and enforcement of the fuel economy standards

- develop policies for introducing hybrid and alternative fuel vehicles into the market

- develop policies for fuel economy standards beyond 2008; and

- extend the activities above to the other developing countries.

While the Energy Foundation continues to fund some of the activities above, it has limits. First, the scope of the Foundation is limited to China and the U.S. alone. Second, the size of the Energy Foundation—US$30 million in grants annually for U.S. and Chinese programs altogether—is not enough to cover the wide range of financial needs for energy efficiency policy development in East Asia. The Policy Development Fund proposed here will complement the activities of the Energy Foundation so that it can further accelerate the energy efficiency policy of the Chinese automobile sector ranging from standards setting, revision, implementation, monitoring, enforcement and ex-post evaluation, as well as the introduction of hybrid and alternative fuel vehicles. The Fund can similarly assist the energy efficiency policies of other East Asian countries.

From a practical point of view, it would make sense for the Policy Development Fund to begin by co-financing ongoing activities with the Energy Foundation in order to share personnel and institutional networks as well as lessons learned, and then gradually acquire its own capacity to develop projects in the areas and countries that are outside the scope or means of the Energy Foundation.

c) Energy implication

While the overall impacts of the fuel economy standards are yet to be analyzed, we can do a rough calculation to see the order of magnitude of the implications on energy. The Chinese automobile sector consumed 90 million tonnes of oil in 2003. If standards cut this use by 10 per cent, nine million tonnes of oil would be saved, amounting to 23 Mt CO2. Support from the Energy Foundation on fuel economy standards so far has been roughly US $300,000 per year. By simply dividing the latter by the former, the results are US$0.04/barrel and $0.01/tonne CO2. Both are very small compared to current oil and CO2 prices that are roughly US$50 per barrel and $30/tonne CO2 at the time of writing. It would surely be worthwhile for donors to invest, as it enhances energy security and mitigates climate change.

Of course, there are many questions about these assumptions, particularly regarding costs and benefits. The concepts are complex for energy efficiency improvement because manufacturers and consumers bear additional upfront costs on one hand, while consumers accrue economic benefits from better fuel economy on the other. Furthermore, oil producers and providers will suffer from reduced revenue. Yet, we are performing the right calculation in light of the objective of international cooperation by the Policy Development Fund. From the donors’ point of view, what matters is the amount of money granted to developing countries versus (1) energy demand eased, which means fewer security concerns in the region, as well as (2) CO2 emission cuts. The rough calculation demonstrates the effectiveness of policy development assistance in this context. There may be some failures in practice, some wrong parameters in calculation and fewer rewards in other countries, but it seems quite certain that policy development assistance would be a very cost-effective measure to mitigate energy tensions and cut CO2 emissions in East Asia.

iii) Low-rolling resistance tires

a) Background

Only about 10–20 per cent of the potential energy in gasoline is actually converted into a vehicle’s motion. The remaining 80–90 per cent is lost through thermal, frictional and standby losses in the engine and exhaust system (Michelin, 2003). One way to improve the overall conversion efficiency is to reduce the rolling resistance of the vehicle’s tires. The rolling resistance is not a measure of a tire’s traction or “grip” on the road surface, but rather a measure of how easily a tire rolls on a surface. A tire with low rolling resistance minimizes the energy wasted as heat between the tire and the road, within the tire sidewall itself, and between the tire and its rim. Rolling resistance of the tires is responsible for about 20 per cent of a vehicle’s fuel consumption. If the tire is under-inflated or not properly aligned, then additional losses occur.

Rolling resistance is typically measured on a complex machine resembling a dynamometer where the actual resistance is expressed in kg/tonne. A 10 per cent reduction in rolling resistance will translate into roughly a one per cent reduction in a vehicle’s fuel consumption, although other factors will of course play a role (Duleep, 2005). One rule of thumb is that tires with low rolling resistance can reduce a passenger car’s fuel consumption by as much as five per cent and a truck’s fuel consumption by 10 per cent.

Recent studies have revealed a surprisingly wide range in rolling resistance among tires. Table 6.2 illustrates the range observed among popular tires sold in Europe (Penant, 2005).

|

| ||

| Observed Rolling Resistance of Tires (kg/tonne) | ||

| Passenger cars (for new cars and replacements) | 14 | 7 |

| Trucks and buses | 8.5 | 5.5 |

| Source: Penant (2005) | ||

The study also showed that there was no correlation between important performance characteristics, such as traction and durability, and rolling resistance. In other words, it was possible to purchase a safe, long-lived tire that also had low rolling resistance. Most of the tires for passenger cars had resistances between 10 and 13, so there is considerable opportunity for improvement. Tires in developing countries will typically have higher rolling resistance because they rely on older technologies.

The situation is different in North America and Japan because auto manufacturers have used tires with very low rolling resistance as part of their strategy to comply with fuel economy regulations. Sometimes manufacturers equip vehicles with low rolling resistance tires for other reasons. In China, for example, Buick equipped its compact cars with ultra-low rolling resistance tires in order to highlight the vehicle’s efficiency (The New York Times, 2006). Buick claims that this action reduced fuel consumption by two per cent. Curiously, Buick does not offer these tires anywhere else in the world.

The rolling resistance of tires in the replacement market is higher than what’s offered on new cars (especially in North America), so the fuel savings from low rolling resistance tires are lost after the original tires wear out. Unfortunately there is no way for consumers to identify and purchase tires with low rolling resistance because they are not labeled with this information. There are several different procedures to measure rolling resistance, so governments cannot immediately establish a Web site or labeling program.

Several countries have begun programs to address rolling resistance in tires. The European Union is working with tire manufacturers to establish either mandatory or voluntary targets for rolling resistance. The state of California has proposed an information program and possibly maximum levels for rolling resistance.

b) What the Fund would pay for

The Fund would support cooperation between government regulatory agencies, tire manufacturers, auto manufacturers and other interested parties to lower the rolling resistance of tires. For example, the Fund might pay to develop the infrastructure to test, label and possibly regulate rolling resistance of tires. Some of the program development steps might include:

- creation and operation of an independent test laboratory to measure tire rolling resistance;

- sponsoring round-robin (or “chain”) comparisons of manufacturers’ test laboratories to improve quality controls;

- creation and maintenance of a database of rolling resistance measurements;

- estimation of energy savings from various policies to lower rolling resistance;

- evaluation of the cost-effectiveness of different levels of regulation;

- development of an energy efficiency label for tires;

- random verification of manufacturers’ claims of rolling resistance; and

- special programs to encourage low rolling resistance tires in trucks and buses.

The Fund could support other activities depending on a government’s desire to address the problem or manufacturers’ willingness to participate. Indeed, the Fund’s first task would be to decide what programs would be most effective to support.

iv) Voluntary Agreements in Industry

a) Background

Voluntary agreements (VAs) are “contracts between the government and industry” that set “negotiated targets with commitments and time schedules on the part of all participating parties” to improve energy efficiency and/or reduce greenhouse gas [[emission]s] (International Energy Agency, 1997). These agreements typically have a 5–10 year timeframe for participants to plan and implement changes. The main advantage of voluntary agreements is that they focus sustained attention on energy efficiency and/or emissions reduction goals, instead of a campaign-style approach in which attention disappears at the end of a short period of intense activity. Starting in the 1990s, voluntary agreements by industry have significantly improved efficiency in industrialized countries. While there are certainly examples of programs that did not work, successful programs have doubled rates of efficiency improvement compared to rates without the programs. Voluntary agreements spur technological adaptation and innovation by encouraging companies to invest in energy efficiency and by creating a market for energy-efficient products (Delmas and Terlaak, 2000; Dowd, Friedman and Boyd, 2001).

The first step in a voluntary agreement is a decision on targets. Governments typically use incentives and disincentives to encourage industry participation. Supporting programs and policies, such as facility audits, assessments, benchmarking, monitoring and information dissemination plays an important role in helping participants understand and manage their energy use and greenhouse gas [[emission]s]. Some of the more successful voluntary agreement programs also offer tax reductions. In the United Kingdom, companies participating in voluntary agreements are eligible for an up to 80 per cent rebate on fuel consumption taxes. If implemented within a comprehensive and transparent framework, international experience shows that voluntary agreements are an innovative and effective way to motivate industry to improve energy efficiency and reduce related emissions (Croci, 2005).

China is showing increased interest in this approach. Under a program initially sponsored by the Energy Foundation, two steel plants in Shandong entered into pilot voluntary agreements. These pilot agreements had several important supporting policies, but were missing some of the financial incentives found to be important in other countries. Nevertheless, initial results were deemed successful enough that a number of local governments began instituting VA programs of their own, and the national government has made VAs an element in a major energy efficiency initiative financed in part by the GEF. UNDP is overseeing this program, the End-Use Energy Efficiency Program, which has US $1.5 million allocated for additional pilot agreements with 12 enterprises in the steel, cement and chemical industries.

There is potential for China to integrate a voluntary approach into a new program being designed to monitor the energy performance of its top 1,000 energy-consuming industrial enterprises. This “Top 1,000” program will incorporate “energy efficiency agreements” overseen by local governments, with benchmarking to domestic and international standards, target-setting, auditing, monitoring, technical and financial supporting policies, and annual and five-year evaluations.[2] The U.K. is currently advising China on the Top 1,000 program based on its experience with Climate Change Agreements and Climate Change Levy,[3] and may second a staff member to Beijing for a significant portion of 2006 for this purpose.

Despite the presence of these and other assistance projects (such as the European Union’s Energy and Environment Program[4]), there is still significant room for additional efforts to broaden and accelerate the implementation of VAs. A great deal of work is needed in designing supporting policies, i.e., the fiscal and tax measures and technical assistance needed to encourage investment, as well as in building the institutions of implementation, particularly independent, objective monitoring and assessment systems.

b) What the Fund would pay for

The fund could leverage its contribution by supporting one key aspect of VA development. As just one example, the Fund could develop a government standard on industrial energy management systems that would be implemented as part of the Top 1,000 program. The standard would require companies to adopt a “best practices” approach to energy efficiency and document results, e.g., through existing ISO documentation procedures, or adopting practices from Japan or other countries that have demonstrated successful approaches. To be effective, energy management programs require training, which could be offered as part of a voluntary agreement, and also partly supported by the Fund. The energy management system standard would be flexible, non-prescriptive (in the sense of not recommending specific technologies or energy targets) and verifiable. Compliance with the standard could be a condition for remaining in the Top 1,000 program. Complementarity with ISO management systems could also be contemplated in designing the energy management system standard.

There are other examples that could be put forward. The keys would be (1) to work with the appropriate agency in China to define a specific task within the larger VA program that would benefit from international participation; (2) to coordinate the activity with other international organizations currently involved in the sector; and (3) to ensure that the principles abstracted from experience from abroad are applied to the circumstances that currently exist in China rather than attempting to transplant an activity that was developed under very different conditions.

c) Energy implications

Programs that target the industrial sector are essential to meeting China’s ambitious targets for improving efficiency, such as the much-reported target of reducing overall intensity of the economy by 20 per cent from 2005 to 2010. Industry consumes about 70 per cent of total commercial energy in the country (National Bureau of Statistics, 2005). In 2004, the top 1,000 enterprises accounted for nearly half of this, or about 33 per cent of total energy consumption[5]. If these agreements can assist the enterprises to improve energy efficiency by an additional five per cent over the next five years, if there is 10 per cent annual growth in energy use at these large firms (assuming continued strong economic growth and increasing market share of China’s large firms), VAs could help to reduce energy use by the equivalent of about 75 Mt of coal per year. While this represents less than three per cent of current energy use, it is still a large potential gain from a single program, and in a sector that has been notably lacking in effective policy activity in recent years.[6]

C. Political feasibility with key stakeholders

Political feasibility is necessary for the success of any policy proposal. A well designed incentive structure is crucial. In what follows, we assess the political feasibility of the Fund proposal in terms of costs, benefits and incentive structure.

Macro-level

On the macro-level, the Fund addresses many key national interests as we discussed in Section 2.3 (Cooperative Climate: Chapter 6). The benefits include energy security, economic efficiency, pollution reduction and climate change mitigation. Some of these national interests have been present for decades, but some are new, and the importance of energy efficiency policy is constantly increasing, given burgeoning economic development, energy consumption growth, mounting environmental concerns and territorial tensions in the region. The time is ripe for further enhancing regional cooperation on energy efficiency policies that fit well with the national interests of all sides.

Micro-level

Macroscopic incentives at the national level are not enough for an international policy to be stable. In what follows, we will carefully assess the costs and benefits of key actors to see the political feasibility of the Fund proposal.

Division of responsibility between the government and private sector

The division of responsibility in the Fund is that the national governments set regulatory systems, the private companies provide technical support in developing the regulatory systems, and do their profit-maximizing business within these regulatory systems. It is important to note that each of these elements is feasible and this division of responsibility is in harmony with their ordinary division of responsibility on any business activities.

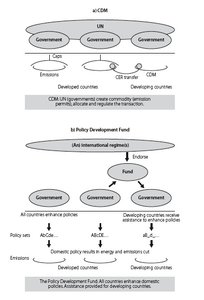

It is in strong contrast with the CDM which has many barriers to widespread implementation as we reviewed in [[Chapter 2 (Cooperative Climate: Chapter 6)]2]. With CDM credits, the international organizations (UNFCCC, COP, EB and the Panels) create a commodity (emission permits) and control the flow of the commodity across countries. It is different from any other commodities for which commercial transactions exist in the first place, and the regulatory system kicks in later to modify the existing commercial transactions. For most commodities, except for the CDM, the role of the international organizations is not to create the commodities but to modify the flow of commodities. While the CDM is facing such an unprecedented challenge, and its future remains highly uncertain, the Policy Development Fund relies on traditional divisions of responsibility which has proven to be successful in policy development for energy efficiency in many countries.

Donor countries

Japan will be the most important donor country in the region. Judging by the amount of money spent in the area of climate change and international cooperation, including official development assistance (ODA), the proposed budget of US$10–30 million per year at the beginning, seems feasible considering the benefits outlined below.[7]

The benefits of the Fund to Japan (and any other potential donors) are huge and multi-faceted, as described above. In addition, political support will be secured since the Fund’s principles will resonate well with the Japanese people, who have strong confidence in technology, particularly in energy efficiency. Also, they are generally willing to cooperate with other Asian countries. This combination of characteristics will be attractive to political leaders.

However, in the course of interviews with Japanese policy-makers, we found that there was some skepticism about the Fund because they thought that developing countries, in particular China, are rich enough to implement energy efficiency policies if they are really interested in them. As evidence of this wealth, they pointed to the build-up of arms, including the navy and nuclear missiles, the space station program, nuclear power development, Chinese strategic ODA to less developed countries, including North Korea and Pakistan, and the luxurious lifestyles of the emerging rich class in big cities. They are also worried that China’s strength is disturbing the welfare and peace of neighboring Asian countries.

The authors understand these concerns but think differently. First, China is going to be a superpower anyway. In more than 2,000 years of East Asian history, China has been the strongest and biggest country in the region, with the past several decades being rather exceptional.

Second, being a big economic and political player per se is not the source of the problem. What matters more than size are China’s characteristics. If China loves peace and appreciates the environment, it will be a most reliable and close friend to all countries in the region. If China is expansionist and refuses to cooperate in securing the environment, it may pose a serious problem regardless of China’s size. What we should do is to work with China so that it grows smartly, with more economic efficiency, more trade and investment with the world, good integration with the global system, and sharing the same key values as the rest of the world in terms of peace and the environment. If the rest of the world is reluctant to assist China to grow peacefully in an environmentally-friendly way, there would be a danger that China would become hostile to the rest of the world, expansionist and would damage the global environment.

Third, even if developing countries have enough financial resources as a whole, and the awareness for energy conservation policy is high at the political level, it is often the case that the office in charge of energy efficiency policy is understaffed and poorly funded. Any national system, particularly if it involves budgetary and personnel issues within government, is difficult to change in a short time. By filling the gap, the Fund will be critical for putting energy efficiency policy in place.

Fourth, despite all possible efforts to keep countries prosperous and peaceful, the region may become politically unstable. Establishing a link and keeping a network of people involved in energy efficiency cooperation will be useful for preventing such political failure and will serve as a safety net for maintaining contact within the group of people across political boundaries in case of such failure.

Overall, when we talked with Japanese policy-makers and stakeholders from government and industry, we found that they were generally in favor of the idea of the Fund and they agreed that there are common national interests in energy efficiency improvement. They had mixed views about Japan’s past experience in energy efficiency cooperation, but agreed that new concepts are needed given the changing national circumstances in the region.

From the interviews, we also found that the concept of policy development assistance was not yet well understood in Japan, so it may be worthwhile to elaborate and promote the concept further. Moreover, those who understand the concept wonder if it might be too intrusive to be accepted by developing countries, given that the memory of World War II remains fresh in some countries.

Regarding the last point, however, our literature research and interviews with policy-makers and business stakeholders in developing countries revealed that recipient countries would not see the Fund as problematic if it was carefully designed; voluntary, not mandatory, in nature; focused at the technical level (not comprising overall policy reform, such as IMF structure adjustment); and was in a multilateral, not a bilateral, setting. Our Fund proposal reflects these inputs.

Recipient countries

The benefits of the Fund for the recipients are multi-faceted and significant, as described above. Our series of interviews revealed that they are generally favorable to the concept of the Fund. Moreover, they are already accustomed to the concept of policy development assistance in the area of energy efficiency. This means that Japan does not have to worry if it is not politically feasible.

Another important aspect is that the proposal is in line with current policy direction. In China, energy in general has received increasing political attention in recent years. Our interviews underscored that there is a renewed will to do something about improving efficiency as represented by the ambitious Chinese long-term plan (see Section 2.2 (Cooperative Climate: Chapter 6) for details).

Manufacturers of traded appliances and automobiles

International manufacturers—or their affiliates for traded appliances and automobiles—benefit from the Fund’s activities, or at least are not adversely affected by them. Promotion of energy efficiency policy for standards and labeling in particular, sometimes associated with the harmonization of testing patterns, will provide a competitive edge to international manufacturers with the capacity to incorporate cutting-edge technologies to their products.

On the other hand, minor and local manufacturers may consider Fund activities bad for their business if they lack the capacity to incorporate cutting-edge technologies. They may fail to comply with more stringent requirements for energy efficiency improvement.

In the real world, actual regulatory levels are the outcome of trilateral politics among frontrunner manufacturers, laggard manufacturers and governmental regulatory authorities in each county. Consumer groups and NGOs sometimes join these politics. Moreover, another economic dimension exists in the context of China. There is a tension between the central regulatory authorities, who want to promote more energy efficiency policy from a national energy security perspective, and local governments that want to keep their local economies running. Both have legitimacy and the Fund will never aim to change the structure. What the Fund will do is facilitate the process by providing better information to all sides so that there will be better outcomes for all. The Fund does not prescribe the answer and the final say is always left to the individual recipient country.

Manufacturers of traded raw materials

Steel, cement and non-steel metals are examples of traded raw materials. Manufacturers of traded raw materials in developed countries may find it is against their interests for their governments to donate to the Fund. This is true if the Fund activities result in more efficient production from competitors in recipient countries that reduce [[market]s] for the products made in developed donor countries. These are legitimate concerns.

However, four remarks address these concerns. First, the companies in developing countries will also bear the short-term upfront costs of meeting energy efficiency requirements, even if they have higher cost savings and competitiveness in the long run. It is fair competition because the fruits are not given for free, but are available only to those who make a series of efforts by themselves.

Second, the scheme is much more acceptable than the CDM, in which additional investment costs for energy efficiency improvement are borne by the developed countries. That means manufacturers located in developing countries do not have to bear any costs for energy efficiency improvement. While it could be legitimized by North-South philosophical debates, doing this on a massive scale would be unacceptable to manufacturers in developed countries.

Third, international manufacturers based in developed countries often have affiliated companies in developing countries. They will surely have a competitive advantage over the local and minor manufacturers in developing countries that do not possess the technological capacity to meet more stringent energy efficiency requirements. As such, the joint profits of the cross-border companies are not necessarily negative. Altogether, costs and benefits are difficult to assess for these manufacturers in general, and perhaps differ among companies.

Fourth, even if some raw material manufacturers from developed countries become less competitive, stricter requirements for energy efficiency in developing countries may open up more attractive business opportunities. They include high-tech materials for insulation and lighting in buildings, strong and light materials for automobiles, and engineering services with information technologies.

Given the considerations above, manufacturers in developed countries are not likely to be the losers. Rather, the more obvious potential losers are, again, local and minor manufacturers in developing countries. The same considerations for manufacturers of traded appliances and automobiles apply here. The Fund’s activities should not be intrusive, but should provide technical assistance for consideration, and leave final decisions to each sovereign country for finding a balance among the many legitimate concerns, including the development of local manufacturing capacity and local employment.

Given the above considerations, the Fund activities for the manufacturing sector and traded raw materials are, as a whole, an attractive option for governments in developed as well as developing countries, with different consequences for individual manufacturers.

Manufacturers of non-traded products

The power utility and building sectors are examples of non-traded products. In this category, there is less conflict of interest between manufacturers from developed countries and those from developing countries. The market is closed in each country, so there is no competition between countries. For example, China will not export electricity to Japan even if it achieves higher efficiency and lower costs.

CEO and the Secretariat of the Fund

Unlike other players, the CEO and Secretariat are less interested in mundane benefits than in value. Salaries are of course necessary, but the most talented people in the world working in the area of energy efficiency and climate change cooperation are primarily working for values such as better environment; a good life; more energy security and peace; and more affordable standards of living for the poor. Providing the institutional platform, political endorsement and appropriate funding to these people, and asking for their devotion, are the keys to success.

D. Cost-effectiveness of the Fund

With the Fund proposal, we can cover a wider range—energy product markets, sectors or nations—in order to transform the national energy equipment market toward more efficiency, rather than addressing energy savings at a single site.

If donor countries have infinite resources and recipient countries are willing to take advantage of the cost-effective opportunities afforded by energy efficiency policy, then the energy saving potential of the Fund activities is equal to the technical potential of the energy savings in recipient countries. Let us call it theoretical potential.

However, there are two factors that prevent the theoretical potential from materializing. One is the cost-effectiveness of the projects under the Fund and the other is the donor countries’ willingness to pay. Let us name it practical potential and examine it. The project examples provided in item B(i) and B(iii) above showed a rough estimate that the most effective projects can be executed at the range of US$0.10 per ton of CO2 or less in terms of the amount of foreign aid donated versus a ton of CO2 saved. To be conservative, let us assume the costs are US$1 per ton of CO2. The willingness to pay by the donor countries is not easy to estimate, but the authors think US$100 million per annum will be feasible.[8] Dividing the latter by the former makes 100 million tons of CO2 per annum. This is a significant amount compared to Chinese annual CO2 emissions from the energy sector of 4,100 million tons (in 2003), and Japanese annual CO2 emissions from the energy sector of 1,200 million tons (in 2003). Of course, if the cost-effectiveness is as high as US$0.10 or less as the rough calculation provided in the item B(i) and B(iii), then the practical potential will reach the theoretical potential of Asia. If wisely done, most energy efficiency potential in East Asia can be realized at a level of US$100 million per annum.

So far, the calculation has been done in terms of the amount of money donated to the Fund versus the CO2 saved. However, different calculations can be done. If the Fund is a “revolving” fund, or a fund to which the revenues accrued from energy savings are recycled, then there is no need for continuous payment, but only one upfront contribution from donor countries. Such a revolving fund is possible since energy savings generally result in economic benefits for the recipient countries, although identifying the exact beneficiaries among many stakeholders is not a straightforward matter. Having a loan instead of a donation is a similar idea and would also be politically feasible.

E. A future scenario

While it is unlikely that the Fund activities will be recognized as a CDM activity under the Kyoto Protocol (Kyoto Protocol to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (full text)) in the very near future, it is possible that they will become part of the post-Kyoto framework after 2012 because the Fund provides opportunities for nations and companies alike to work on energy efficiency and climate change mitigation. The fund can be housed either under the UNFCCC or other schemes such as the Asia-Pacific Partnership for Clean Development and Climate (APP). See Figure 6.4.

In the current political context, it is unlikely that many countries, including China, the greenhouse gas and Japan, will agree on a set of Korea emission reduction targets and timetables for 2012 and beyond in the UNFCCC process. Currently, the countries are very divided in the process. While COP-11 in Montreal decided that there would be a “dialogue” on the post-Kyoto regime, there have been such strong caveats that the dialogue would lead neither to negotiation nor commitment.

Against this backdrop, we describe a scenario in which the Fund will be established outside the UNFCCC, in order to share with the readers the possible development of the Fund over time. The scenario is not a prediction or desired future, but represents one potential direction for the future.

Fund scenario and timeline:

2006

Japan, Korea, China, the Philippines, Indonesia and the U.S. announce the establishment of the Policy Development Fund for Energy Efficiency in East Asia. It is endorsed by the APP. The donor countries—Japan, Korea and the U.S.—announce they will pay US$10 million annually for the coming five years.

Co-financing of energy efficiency policy development in the automobile sector of China begins in coordination with the Energy Foundation. Co-financing of standards and labeling programs in participating countries begins in coordination with CLASP.

2007

It becomes clear that only European countries remain in the binding emissions cap regime after 2012. Heated political debate in Japan as to whether it should remain in the regime or not without participation by any other non-European developed countries.

From this year on, a mounting number of “actions,”which are new laws, standards and other policies for energy efficiency are reported in the annual ministerial meetings of the Fund.

2008

The activities in 2007 are reported to the G8 summit in Tokyo. The estimate of cost-effectiveness is US$0.10 per ton of CO2 donated. The estimate of total CO2 reduction is 100 million tons of CO2 per annum. The estimated emission reductions by energy saving outpace those from the CDM. While total emissions are increasing in most countries, the development of thi institution is welcomed as a good signal for change. The G8 ministers celebrate the success of the Fund. Japan announces plans to increase its donation to the Fund to US$30 million per year. Some major international companies also begin donating to the Fund as part of their voluntary demonstration of corporate social responsibility (CSR).

2009

The Fund begins to address new projects including industrial boiler efficiency improvement and industrial voluntary agreements to improve efficiency in China.

2010

The progress of energy conservation policy attracts interest from non-member developing countries that wish to improve their economic efficiency and global competitiveness, and membership increases. Attracted by the record of success, more developed countries with environmental concerns join the funding mechanism. By this year, most of the ASEAN countries and India have joined the Fund as recipients. European countries also join the Fund. African and Latin American versions of the Fund are established.

2011

Manufacturers increase their expectations of more stringent global energy efficiency regulation in the future. They agree with the government to tighten the efficiency standards and labels in developed countries given the mounting expectation that highly-efficient appliances will find the Asian market in the near future.

6.3 Summary

In this chapter, the Policy Development Fund for Energy Efficiency in East Asia is proposed. The Fund is intended to meet the national priorities of participating countries; to aim for massive energy savings and significant emissions reductions through market transformation and leverage of private sector resources; and to commit to concrete actions and support policy mechanisms for such actions.

The major characteristics can be summarized as follows:

1. Political agreement

The Fund begins with a small number of countries and expands later. It starts with multilateral agreement from the outset to avoid capture by narrow interests, but the number of initial participants is kept small to emphasize areas of agreement and achieve alignment of interests.

2. Design of the Fund

- The Fund is new and dedicated to energy efficiency. A new and dedicated fund can respond more quickly, in contrast to the lengthy project procedures required by international organizations established for other purposes, such as development aid.

- The management structure (CEO, Executive Board, staff) is independent and professional in order to insulate itself from short-term political changes.

- The activities are restricted to the region and to energy efficiency only to secure the alignment of interests and effective management.

- Like-minded countries in East Asia join the independent Fund. Financial contributions are voluntary. Expected initial scale: US$10 million annually. Private sponsors may also contribute.

- The Fund supports formulation and initial implementation of energy efficiency policy in member countries. Recipients commit themselves to implementation.

- Recipients, not donors, retain discretion over types and stringency of policy measures.

- The CEO makes decisions, including project selection, under the guidance of the Executive Board. The CEO is nominated by the Executive Board.

- Projects are selected by the CEO using cost-effectiveness as a key criterion. Cost-effectiveness is defined as energy savings or CO2 reductions per amount of grant.

- The Fund supports new projects and provides co-financing for existing efforts.

3. Projects

The Fund’s potential target technologies and sectors vary widely, given the broad definition of the Fund—policy development for energy efficiency. Since nearly all sectors in developing countries need further policy development ranging from information gathering, law stipulation, standard-setting, monitoring, enforcement and revision, there is almost an infinite list of potential areas of cooperation. An indicative list of projects is provided in Table ES1 (Cooperative Climate: Chapter 6). Four examples are provided in section 6.2 B to further illustrate how the Fund works.

The estimates of the cost to a government to institute and maintain an energy efficiency policy that induces cost savings, energy savings and emission reductions have been scarce so far, but some early estimates indicate that the costs are typically less than US$0.10 per ton of carbon.

Notes This is a chapter from Cooperative Climate: Energy Efficiency Action in East Asia (e-book). Previous: Part III. Proposal for a New Energy Efficiency Policy Development Fund (Cooperative Climate: Chapter 6) |Table of Contents (Cooperative Climate: Chapter 6)|Next: A Final Word from Co-editor Taishi Sugiyama

Citation

Development, I., Meier, A., Sinton, J., Sugiyama, T., & Wiel, S. (2012). Cooperative Climate: Chapter 6. Retrieved from http://editors.eol.org/eoearth/wiki/Cooperative_Climate:_Chapter_6- ↑ See footnote 7 for examples of relevant budget size.

- ↑ Wang Xuejun, Professor, College of Environmental Sciences, Peking University (April 2006), personal communication.

- ↑ For further information, see: <a class="external free" href="http://www.defra.gov.uk/Environment/ccl/" rel="nofollow" title="http://www.defra.gov.uk/Environment/ccl/">http://www.defra.gov.uk/Environment/ccl/</a>

- ↑ For further information, see: <a class="external free" href="http://www.delchn.cec.eu.int/en/Co-operation/Project_Fiches.htm" rel="nofollow" title="http://www.delchn.cec.eu.int/en/Co-operation/Project_Fiches.htm">http://www.delchn.cec.eu.int/en/Co-operation/Project_Fiches.htm</a>

- ↑ Wang Xuejun, Professor, College of Environmental Sciences, Peking University (April 2006), personal communication.

- ↑ It is also worth noting that the planned Top 1,000 program would contain elements that are essential to the design of CDM projects. In particular, the benchmarking, target-setting and regular reporting of energy performance have the potential to set a credible basis for reporting emissions reductions that meet strict definitions of additionality.

- ↑ We think the budgetary size is feasible based on a rough comparison with the potential budgetary sources in Japan. Major budgets relevant to climate change and energy efficiency policy include: “global warming budget,” which is JPY 1.3 trillion or US$13 billion at the exchange rate of US$1=JPY100; “special account for oil-substitute” is JPY 0.5 trillion or US$5 billion; “special account for power locating” is JPY 0.5 trillion or US$5 billion. These two special accounts are dedicated for energy security and climate change mitigation. ODA to China is decreasing, but still as such as JPY 0.2 trillion, or US$2 billion in FY2005. There can be political feasibility if the contribution to the Fund is small relative to the budgets. US$10 million initially and increasing it to US$100 million in the long run for energy security and climate change mitigation would be feasible in this regard.

- ↑ This guess is based on a rough comparison with the potential budgetary sources in Japan. See footnote 7 for the discussions on feasibility.