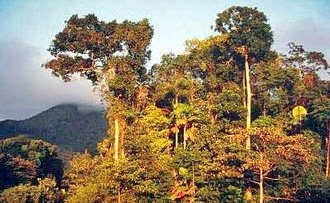

Queensland tropical rainforests

The Queensland tropical rainforests of Australia contain most of the world’s present day relict species of the ancient Gondwanan forests. The rainforests contain the most complete and diverse living record of the major stages in the evolutionary history of the world’s land plants, as well as one of the most important living records of the history of the marsupials and the songbirds.

High concentrations of endemic monotypic genera and primitive plant families reflect the Refugial nature of many parts of the ecoregion. These rainforests also provide an unparalleled living record of the ecological and evolutionary processes that shaped the flora and fauna of [[Australia] ]over the past 415 million years, although the Queensland tropical rainforests are only about as old as 70 million years as a stable time continuous ecological system.

Location and General Description

Queensland’s tropical rainforests are located in the narrow coastal, high rainfall belt of northeastern Australia on steep to undulating plateaus lying between 600 to 900 metres (m), with mountain peaks rising to 1622 m. Coastal lowlands along the Coral Sea are linked to the higher country through steep, rugged escarpments, ranges, and foothills.

This ecoregion consists of three disjunct areas along the Queensland coast, the largest of which includes Cairns and extends from 15°30’S down to 19°25’S. Further south, the second largest section includes Mackay, and extends from the Whitsunday Group down to Carmila. Finally, the smallest and southernmost region includes the Warginburra Peninsula and extends inland to include portions of the Normanby Range.

The region’s rainforests possess elements representative of tropical, subtropical, temperate, and monsoonal forest types found elsewhere in Australia and occur across a diverse range of geologies, altitudes, and evolutionary histories resulting in a spectrum of plant communities which are floristically and structurally the most diverse in Australia. The rainforests have been classified into 16 major structural types and 30 broad community types. These rainforest types are fringed and dissected by a range of eucalypt forests and woodlands, mangroves, and Melaleuca swamp communities.

Mean annual rainfall ranges from 1200 millimeters (mm) to over 8000 mm and is distinctly seasonal with 75 percent to 90 percent occurring between November and April. Widely differing rainfall regimes are characteristic and may vary considerably even over short distances because of changes in local topography, including height and orientation of mountain ranges, and the direction of the coastline with respect to the prevailing moist southeast airstream. There is a very pronounced orographic influence with higher averages centered around the higher peaks and their eastern slopes. In general, rainfall is highest in the northern section and lowest in the southern section. The potential ecological range of rainforest vegetation includes most areas receiving greater than 1500 mm average rainfall per annum, with a driest quarter rainfall in excess of 75 mm. The wettest rainfall recording station is on the summit of Mount Bellenden Ker which averages 8529 mm per year.

Melaleuca communities replace rainforests on the most seasonally waterlogged soils while eucalypt woodlands replace rainforests on poorer podsolic soils. Where soil and rainfall are not limiting, fire becomes the principal rainforest or eucalypt open forest/woodland controlling factor. Where rainfall is less than 1,500 mm per annum, rainforest is restricted to alluvial soils along streams and sheltered gullies on south-facing slopes. Tropical cyclones are a feature of the climate and are a major factor shaping the structural and floristic differentiation of the vegetation.

The peak development of rainforests in the region is as low altitude complex mesophyll vine forests on wet fertile alluvial and basaltic soils where plank buttressing is common, robust woody lianes, vascular epiphytes and palms are typical, and fleshy herbs with wide leaves (e.g. gingers and aroids) are prominent. Exposed sites often exhibit cyclone disturbed broken canopies with ‘climber towers’ and dense vine tangles. Notophyll vine forests embraces a structurally and floristically diverse group of communities. Complex types with emergent kauri pines (Agathis spp.) typically occur on the western and northern fringes of the main rainforest massif on granite and metamorphic foothills and uplands. In the northern part of the region the characteristic kauri pine species segregate into altitudinal zones - Agathis robusta being replaced by A. microstachya and A. atropurpurea with increasing elevations. South of the Herbert River Gorge Agathis spp. are replaced by hoop pine (Araucaria cunninghamii). In two very restricted areas bunya pine (Araucaria bidwillii) are canopy dominants. These communities, while extraordinarily variable, are characterized by the occurrence of rattans or palm lianes, strangler figs, frequently conspicuous epiphytes and variable amounts of ferns, walking stick palms, and fleshy herbs. Simple microphyll vine-fern thickets dominate the summits and upper slopes of the higher peaks, which are frequently covered by clouds and often exposed to strong winds. Aerially suspended moss is a common feature of these forests.

Biodiversity Features

The final stage in the break-up of Gondwana had a profound effect on global climates. When Australia was still attached to Antarctica, warm equatorial currents reaching polewards ensured an equable wet and warm climate. The detachment and northward drift of the Australian continent allowed the development of circumpolar currents, the formation of the Antarctic ice cap, and extensive species extinctions. However, the effects of global cooling and accompanying aridity were maximally compensated for in the Queensland Tropical Rainforests ecoregion by the northward drift of Australia towards the tropics.

As a consequence of this movement and the wide range of available altitudinal gradients, this ecoregion is the only part of the entire Australasian region where rainforests have persisted continuously since Gondwanan times, preserving in the living flora the closest modern-day counterpart of the Gondwanan forests. Much of the world’s humid tropics is of ‘recent origin’, and although these newly expanding environments generate areas of exceptional species richness, they generally have surprisingly low levels of endemism. However, the long-isolated and ancient floras of New Caledonia, Madagascar, and Queensland’s tropical rainforests have very high levels of endemism and are significant as diverse pools retaining of genetic material over the widest evolutionary time span. Queensland's tropical rainforests as a center of endemism differs from other areas of long-isolated floras in that it is part of an ancient continental as opposed to island landscape, uplifted more than 100 million years ago and tectonically stable for the greater part of the period of angiosperm evolution.

Queensland’s tropical rainforests, although accounting for only 0.3 percent of the Australian continent, conserves an extraordinarily high level of Australia’s biodiversity. Among the plants, this ecoregion provides habitat for 65 percent of Australia’s fern species, 21 percent of its cycad species, 37 percent of its conifer species, 30 percent of its orchid species, and 17 percent of its vascular plants. Thirty-six percent of Australia’s mammal species are found here, including 30 percent of the marsupial species, 58 percent of the bat species, and 25 percent of the rodent species. A full 50 percent of Australia’s bird species are found here, as are 25 percent of its frog species, 23 percent of its reptile species, 41 percent of its freshwater fish species, and 60 percent of Australia’s butterfly species.

Within the ecoregion there are over 4,700 species of vascular plants, representing 1180 genera and 210 families. Forty-three genera and 23 percent of the region’s plant species are endemic. Endemism is particularly high in 33 angiosperm and six gymnosperm, and fern families, most of which are ancient or primitive with restricted relict distributions. There are 70 species recorded only from the type locality and another 80 restricted endemic species for which current records indicate a north–south distribution of less than 25 kilometers (km). Of the endemic genera 75 per cent are monotypic and none contain more than a few species. Thirty-one of the 36 known families, and 111 of the 364 described genera of pteridophytes are found in the ecoregion. The ecoregion also contains 88 percent of the fern genera and 64 percent of the species occurring in Australia.

One of the outstanding features of Queensland’s tropical rainforests is that it contains a high diversity of ancient taxa representing long evolutionary lineages. All seven of the ancient fern families from the world’s existing flora of about 36 families occur in the region (Lycopodiaceae, Selaginellaceae, Ophioglossaceae, Marattiaceae, Osmundaceae, Schizaeaceae, and Gleicheniaceae). Eighteen out of the 27 genera from all seven families are represented in Queensland’s tropical rainforests by 41 species. Twelve of the world’s 19 primitive angiosperm families are represented in the region, including Annonaceae, Austrobaileyaceae, Eupomatiaceae, Himantandraceae, Myristicaceae, and Winteraceae from the order Magnoliales and Atherospermataceae, Gyrocarpaceae, Hernandiaceae, Idiospermaceae, Lauraceae, and Monimiaceae of the Laurales. Two of these families, the monospecific Austrobaileyaceae and Idiospermaceae, are endemic to Queensland’s tropical rainforests.

At least 672 terrestrial vertebrate species have been recorded in the region which represents 32 percent of Australia’s terrestrial vertebrate fauna. Of this total 264 species are confined to rainforests. The level of regional vertebrate endemism is high being 12 percent for mammals, four percent for birds, 21 percent for [[reptile]s], 40 percent for frogs, and 10 percent for freshwater fish. The overall level of regional vertebrate endemism is 11 percent. Most of these endemics are confined to rainforests above 400 meters altitude, and many are considered to be relicts from formerly widespread temperate environments.

Eleven species and eight subspecies of mammal are restricted to the ecoregion. Of the 370 bird species recorded from all habitat types in the ecoregion, 130 species principally inhabit rainforests, and 13 species are totally confined to the upland rainforests. A further ten species have their Australian distributions confined to the ecoregion and at least another ten bird subspecies are restricted to the ecoregion. Of the region’s 170 reptile species, 22 are endemic including 16 skink species. Twenty-one species, or about ten percent of Australia’s frogs, are endemic to the region. All but one of the endemic species are rainforest-dependent. The region provides habitat for 78 of Australia’s 190 species of freshwater fish, 8 of which are regional endemics.

A number of globally threatened species are found in this ecoregion, some of them endemic. Globally endangered amphibians include nine species of endemic frogs, the armored frog (Litoria lorica CR), torrent tree frog (Litoria nannotis EN), nyakala frog (Litoria nyakalensis CR), common mistfrog (Litoria rheocola CR), Australian lace-lid (Nyctimystes dayi EN), Eungella gastric-brooding frog (Rheobatrachus vitellinus EN), sharp-nosed torrent frog (Taudactylus acutirostris CR), Eungella torrent frog (Taudactylus eungellensis VU), and tinkling frog (Taudactylus rheophilus CR). The southern cassowary (Casuarius casuarius VU) is endemic to this ecoregion and globally threatened mammals include a subspecies of the endangered mahogany glider (Petaurus australis reginae), the northern bettong (Bettongia tropica EN), spotted-tail quoll (Dasyurus maculatus gracilis EN), and the false swamp rat (Xeromys myoides VU).

Evolutionary Origins, Geology and Climate

While Austalia as a whole has traceable geomorphological history dating back around 415 million years, there has been a considerable geological stability for the Queensland region since approximately 180 million years before present, based upon the integirty of the continental divide since that era; furthermore, there has been a remarkable ecological stability of these rainforests since at least the late Mesozoic, making the Queensland tropical rainforests some of the most primitive on Earth, in the sense that there composition may have changed relatively little over such an extended period.

The origin of the Great Dividing Range is thought to be uplift subsequent to continental rifting and contemporaneous formation of the Coral Sea. While the Queensland landmass existed before the uplift was complete, the regional landform in its present general extent took shape by the late Mesozoic.

The Great Dividing Range controls the prevailing airflow and rainfall in the region. To the south the ridgeline is almost parallel to the prevailing tradewinds, so that the resulting uplift is slight and rainfall is more modest; conversely, in the northern Queensland tropical rainforests, the tradewinds are oblique to the ridgeline, so that uplift is great and rainfall is high.

Current Status

The Wet Tropics of Queensland World Heritage Area was declared over 8940 km2 of the region in 1988 and includes most of the remaining larger contiguous rainforest blocks and most of the recognized high altitude refugial rainforest areas where high levels of local endemism occur. Logging has been a prohibited activity in the World Heritage Area since its listing. Although 15 percent of the ecoregion is managed as national park, some very significant lowland centers of plant endemism are missing from the protected areas network as are a number of very depleted ecosystems and critical [[habitat]s] for several endangered species.

Of the 105 regional ecosystems identified by Goosem et al., 24 (23 percent) are considered endangered and a further 17 as of concern. Eighteen of the endangered ecosystems occur on the coastal plain as fragmented remnants, with another five confined to the gentle terrain associated with upland basalt tableland landscapes. Less than 20 percent of the original native vegetation of the coastal lowlands remains, much of this severely fragmented and in a highly degraded state. Sugarcane expansion on the lowland plain is an ongoing threat as is the change to more intensive, irrigated agricultural land-use on the upland plateau. Forests within the region are still being cleared at a rate of around 20 km2 per year.

Seventeen plant species are considered to have become extinct during the past 50 years, while 42 plant, three mammal, three bird, nine frog, and two butterfly species are currently listed as endangered by regional or continental standards, with a further 54 plant, seven mammal, five bird, three reptile, one frog, and three butterfly species identified as vulnerable. The large number of presumed extinct plants highlights the vulnerability, small population size and restricted distribution of many of the region’s plants and the pattern and extent of habitat clearing.

Types and Severity of Threats

The region is considered particularly vulnerable to the threat of invasive pest species. Werren identified 508 naturalized plant species in the region. A further seven mammal, five bird, five freshwater fish, two reptile, and one amphibian species have also become naturalized.

Apart from the fragmentation and isolation of rainforest patches resulting from broadscale agricultural land uses, there is also the impact of internal fragmentation of the main rainforest blocks. A network of linear infrastructure, including over 300 km of power line clearings and 1220 km of maintained roads, extend through the rainforest and act as effective barriers to the movement of many rainforest species while providing a conduit for pest and fire intrusion into rainforest areas.

Rainforest dieback associated with Phytophthora cinnamomi has been identified from 190 sites. Rainforests on acid igneous rocks that 14 percent of the region’s remaining rainforests may be susceptible to virulent dieback outbreaks.

Justification of Ecoregion Delineation

The Queensland Tropical Rainforest ecoregion comprises two geographically disjunct IBRA’s, the Wet Tropics and Central Mackay Coast. The region is characterised by high rainfall, Gondwanan heritage, and rainforest vegetation, features which distinguish this region from the drier, eucalypt savannas that surround it.

Further Reading

- For a terser summary of this entry, see the WWF WildWorld profile of this ecoregion.

- Bermingham, Eldredge, Christopher W.Dick, Craig Moritz. Tropical rainforests: past, present, & future. 2005. Unviersity of Chicago Press. 745 pages

- Covacevich, J.A. and P. J. Couper. 1994. Reptiles of the Wet Tropics Biogeographic Region: records of the Queensland and Australian Museums, with analysis. Report to the Wet Tropics Management Authority, Cairns, Australia.

- Crome, F and H. Nix. 1991. Birds. Pages 55-69 in H.A. Nix and M. Switzer, editors., Kowari 1: Rainforest Animals: Atlas of Vertebrates Endemic to Australia’s Wet Tropics. Australian National Parks and Wildlife Service, Canberra, Australia.

- DASETT. 1987. Nomination of the Wet Tropical Rainforests of North-east Australia by the Government of Australia for Inclusion in the World Heritage List. Department of Arts, Sport, the Environment, Tourism and Territories. Canberra, Australia.

- DNR. 2000. Land Cover Change in Queensland 1997-1999. Resource Sciences and Knowledge. Queensland Department of Natural Resources, Brisbane, Australia.

- EPA. 1999. State of the Environment Queensland 1999. Environmental Protection Agency, Brisbane, Australia.

- Gadek, P., D. Gillieson, W. Edwards, J. Landsberg, and J. Price. 2001. Rainforest Dieback Mapping and Assessment in the Wet Tropics World Heritage Area. James Cook University and Rainforest CRC, Cairns, Australia.

- Goosem, S. 2000. Landscape, ecology and values. Pages 14-31 in G. McDonald and M. Lane, editors. Securing the Wet Tropics. Federation Press, Annandale, Australia. ISBN: 1862873496

- Goosem, S., G. Morgan, and J. E. Kemp. 1999. Wet Tropics. Pages 1-73 in P. S. Sattler, and R. D. Williams, editors. The Conservation Status of Queensland’s Bioregional Ecosystems. Environmental Protection Agency, Brisbane, Australia.

- Hilton-Taylor, C. 2000. The IUCN 2000 Red List of Threatened Species. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge, United Kingdom. ISBN: 2831705657

- McDonald, K.R. 1992. Distribution patterns and conservation status of north Queensland rainforest frogs. Conservation technical report No.1. Queensland Department of Environment and Heritage, Brisbane, Australia.

- Queensland Parliamentary Council. 2000. Queensland Nature Conservation (Wildlife) Regulation 1994 (including amendments up to SL No 354 of 2000). Brisbane, Australia.

- Nix, H. 1991. Biogeography: pattern and process. Pages 11-41 in H.A. Nix and M. Switzer, editors. Kowari 1: Rainforest Animals: Atlas of Vertebrates Endemic to Australia’s Wet Tropics. Australian National Parks and Wildlife Service, Canberra, Australia.

- Olsen, M. 1993. Review of vegetation mapping in the southern region of the Wet Tropics. Report to the Wet Tropics Management Authority, Cairns, Australia.

- Pusey, B.J. and M. J. Kennard. 1994. The Freshwater Fish Fauna of the Wet Tropics Region of Northern Queensland. Report to the Wet Tropics Management Authority, Cairns, Australia.

- Switzer, M. 1991. Introduction. Pages 1-11 in H.A. Nix and M. Switzer, editors. Kowari 1: Rainforest Animals: Atlas of Vertebrates Endemic to Australia’s Wet Tropics. Australian National Parks and Wildlife Service, Canberra, Australia.

- Thackway, R. and I. D. Cresswell. editors. 1995. An Interim Biogeographic Regionalisation for Australia: a framework for establishing the national system of reserves, Version 4.0. Australian Nature Conservation Agency, Canberra.

- Tracey, J.G. 1982. The Vegetation of the Humid Tropics of North Queensland, CSIRO, Melbourne, Australia.

- Werren, G. 2001. Environmental Weeds of the Wet Tropics Bioregion: Risk Assessment and Priority Ranking. Rainforest CRC, Cairns, Australia.

- Werren, G., S. Goosem, J.G. Tracey, and J. P. Stanton. 1995. Wet Tropics of Queensland, Australia. 500-506 in S.D. Davis, V.H. Heywood, and A.C. Hamilton, editors. Centres of Plant Diversity: A Guide and Strategy for their Conservation. Volume 2. Asia, Australasia, and the Pacific. WWF/IUCN, IUCN Publications Unit, Cambridge, UK. ISBN: 283170197X

- Williams, S. E., R. G. Pearson, and P. J. Walsh. 1996. Distributions and biodiversity of the terrestrial vertebrates of Australia’s Wet Tropics: a review of current knowledge. Pacific Conservation Biology 2: 327-362.

- Winter, J.W. 1991. Mammals. Pages 43-55 in H.A. Nix and M. Switzer, editors. Kowari 1: Rainforest Animals: Atlas of Vertebrates Endemic to Australia’s Wet Tropics. Australian National Parks and Wildlife Service, Canberra, Australia.

- WTMA. 2000. State of the Wet Tropics. Pages 22-37 in Annual Report 1999-2000. Wet Tropics Management Authority, Cairns, Australia.

| Disclaimer: This article contains information that was originally published by the World Wildlife Fund. Topic editors and authors for the Encyclopedia of Earth have edited its content and added new information. The use of information from the World Wildlife Fund should not be construed as support for or endorsement by that organization for any new information added by EoE personnel, or for any editing of the original content. |

.jpg)

%2c_Australia.jpg)