Bosporus Straits, Turkey

The Bosporus or Bosphorus (also known as the Istanbul Strait) is a straitconnecting the Black Sea with the Sea of Marmara (and beyond it, through the Dardenelles to the Aegean Sea/Mediterranean Sea)

Together with the Dardanelles, the Bophosrus forms the Turkish Straits which separates the European part of Turkey from its Asian part.

The Bosporus is approximnately 19 miles (17 nautical miles/31 km) long. The strait is about 2.2 miles (3.5 km) wide at the northern entrance, narrows to minimum width of 750 meters between Anadoluhisar and Rumelihisar,south of the Fatih Sultan Mehmet Bridge. The depth varies from 36 to 124 meters in midstream. It is a former river valley that was drowned by the sea at the end of the Tertiary period.

The city of Istanbul straddles the Strait with a population of more than 13 million people.

Its strategic importance is high several international treaties have governed vessels using the waters. including the Montreux Convention Regarding the Regime of the Turkish Straits, signed in 1936. It is an important oil transit chokepoint.

Contents

Geography

The Bosporus (Turkish: Boğaziçi) ( separates the European part (Rumeli) of Turkey from its Asian part (Anadolu).

It is crossed by two major bidges: The Bosporus Bridge and the Fatih Sultan Mehmet Bridge

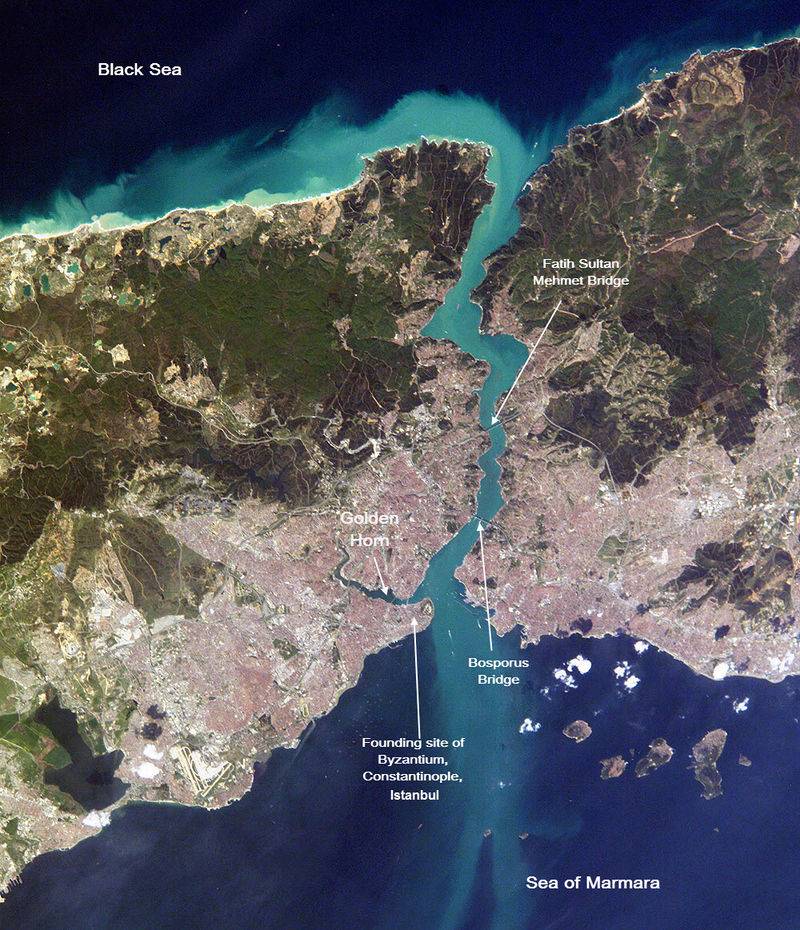

The metropolis of Istanbul occupies both sides of the entrance to the narrow, 20-mile long Bosporus Strait connecting the Sea of Marmara (south and beyond it the Mediterranean) to the Black Sea (north). This digital image was taken by the crew of the International Space Station on April 16, 2004. When this image was taken, strong currents carried turbid coastal waters from the Black Sea through the Strait and into the Sea of Marmara. The rugged uplands to the north of the city are forested and contain vital reservoirs. Source: NASA

The metropolis of Istanbul occupies both sides of the entrance to the narrow, 20-mile long Bosporus Strait connecting the Sea of Marmara (south and beyond it the Mediterranean) to the Black Sea (north). This digital image was taken by the crew of the International Space Station on April 16, 2004. When this image was taken, strong currents carried turbid coastal waters from the Black Sea through the Strait and into the Sea of Marmara. The rugged uplands to the north of the city are forested and contain vital reservoirs. Source: NASA

History

Bosporus means in Greek "ox ford" or "ox passage"; the name comes from a Greek myth about Io's travels after Zeus turned her into an ox for her protection.  Illustration of Ryan and Pitman Hypothosis. Source: NASA

Illustration of Ryan and Pitman Hypothosis. Source: NASA

The origin of the Bosphorus is uncertain. Many researchers hold the view the Black Sea was an isloated fresh water lake until about 9,400 years ago when sea water began to flow from the Mediterranean Sea through the Bosphorus and turned the freshwater lake into the Black Sea.

There is considerable debate about the suddeness of this event, with some arguing that this event was sudden and the source of a massive flood occurring in the region, and is the historic basis for the flood stories in the Epic of Gilgamesh and the Bible (e.g. Ryan and Pitman).

However, many others argue that the event was slower and less dramatic, or that water has flowed perodically between the Mediterranean and the Black Sea in an oscillatory fashion over the past 12,000 years (e.g. Yanko-Hombach).

Because of of its strategic importance as the only water route between the Mediterranean sean and the Black Sea, the Bosporus has been the site of significant settlement and cities for a long time. In particular, the "Golden Horn", a flooded estuary that branches west from the southern part of the Bosporus, creates a large natural harbor off the main strait. This harbor was the site chosen for the city of Byzantium founded by the ancient Greeks about 660 BCE. In 330 AD, the Roman emperor Constantine developed the city at the capitol of the eastern Roman Empire. When the western Roman empire fell, Byzantium continued as a major city and namesake of the continuing eastern empire. In the 12th century, the city was renamed Constantinople, after its founder. In 1453, Ottoman Turks took the city in 1453.

Oil transportation in the Bosporus

An estimated 2.9 million barrels per day (bbl/d) flowed through the Bosorus and Dardelles in 2010, almost all of which was crude oil. The ports of the Black Sea are one of the primary oil export routes for Russia and other former Soviet Union republics. Oil shipments through the Turkish Straits decreased from over 3.4 million bbl/d at its peak in 2004 to 2.6 million bbl/d in 2006 as Russia shifted crude oil exports toward the Baltic ports. Traffic through the Straits increased again as crude production and exports from Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan rose in recent years.

With 50,000 vessels, including 5,500 oil tankers, passing through the straits annually it is also one of the world's busiest chokepoints.

Turkey has raised concerns over the navigational safety and environmental threats to the Straits. Commercial shipping has the right of free passage through the Turkish Straits in peacetime, although Turkey claims the right to impose regulations for safety and environmental purposes. Bottlenecks and heavy traffic also create problems for oil tankers in the Turkish Straits. While there are no current alternate routes for westward shipments from the Black and Caspian Sea region, there are several pipeline projects in various phases of development underway.

The largest oil tankers that can pass through the Bosporus Straits are the Suezmax class tankers (120,000-200,000 dead weight tons).

Oil tankers in the Bosporous Straits.

Oil tankers in the Bosporous Straits. Under the Montreux Convention of 1936, commercial shipping has the right of free passage through the Straits in peacetime, although Turkey claims the right to impose regulations for safety and environmental purposes. In October 2002, Turkey placed new restrictions on oil tanker transit through the Bosporus that have slowed tanker transit, including a ban on nighttime transit for ships longer than 200 meters, effectively including all crude oil and large petroleum product tankers.

In January 2001, work began on building a comprehensive radar and vessel control system for the waterway.

The Bosphorus Strait looking north from the Bosphorus Bridge. Source: Wikimedia Commons

The Bosphorus Strait looking north from the Bosphorus Bridge. Source: Wikimedia Commons

With the high volume of oil being shipped through the Bosporus, oil tanker accidents can release large quantities of oil into the marine environment. This danger was underscored in March 1994, when the Greek Cypriot tanker Nassia collided with another ship, killing 30 seamen and spilling 20,000 tons of oil into the Straits. The resulting oil slick turned the waters of the Bosporus into a raging inferno for five days, but because the accident occurred in the Straits a few miles north of the city, a potential urban disaster was averted.

In the aftermath of the 1994 Nassia disaster, Turkey passed regulations requiring ships carrying hazardous materials to report to the Turkish environmental protection ministry. However, Turkey's power to regulate commercial shipping through the Straits is limited by the 1936 Treaty of Montreux that delineates the Straits as an international waterway. Although subsequent international agreements have given Turkey the right to regulate the right of passage through the Straits to ensure a steady and safe flow of traffic, due to pressure from some Black Sea border countries, Turkey has not been stringently enforcing the shipping laws passed in 1994. Thus, only a small number of vessels passing through the Straits report their cargo. In July 2001, Turkey's environment minister, Fevzi Aytekin, stated that he would use all legal tools at his disposal to stop Russian nuclear waste from being shipped through the Bosporus.

As the number of ships through the Straits grows, the risk of accidents increases, and traffic will likely increase as the six countries surrounding the Black Sea develop economically. With tonnage on the rise as well, the threat of collision is not the only danger: on December 29, 1999, the Volgoneft-248, a 25-year old Russian tanker, ran aground and split in two in close proximity to the southwest shores of Istanbul. More than 800 tons of the 4,300 tons of fuel-oil on board spilled into the Marmara Sea, covering the coast of Marmara with fuel-oil and affecting about 5 square miles of the sea.

In addition, while major spills can bring about immediate environmental consequences, the presence of large oil- and gas-carrying ships in the Straits causes other problems, such as the day to day release of contaminated water as the ships ballast their holds. Pollution in the Straits contributed to a decline in fishing levels to 1/60th their former levels.

Sources and Further Reading

- Yanko-Hombach, V., Gilbert, A.S., Panin, N., and Dolukhanov, P.M., Editors, 2007. The Black Sea Flood Question: Changes in Coastline, Climate and Human Settlement. ISBN 1-4020-4774-6.

- Ryan, W.B.F., and W.C. Pitman III, 1998, Noah’s Flood: The New Scientific Discoveries about the Event that Changed History,.Simon & Schuster, New York

- National Geographic News, 2009, "Noah's Flood" Not Rooted in Reality, After All?"

- Aksu, A., R. N. Hiscott, et. al., 2002. Persistent Holocene Outflow from the Black Sea to the Eastern Mediterranean Contradicts Noah ’s Flood Hypothesis. GSA Today.12:5. (in PDF).

- Oil Trnsit Chokepoints, 2013, Energy Information Administration

|

Disclaimer: This article contains information that was originally published by, the Energy Information Administration. Topic editors and authors for the Encyclopedia of Earth may have edited its content or added new information. The use of information from the Energy Information Administration should not be construed as support for or endorsement by that organization for any new information added by EoE personnel, or for any editing of the original content. |

2 Comments

Peter Boyce wrote: 11-21-2010 06:55:45

The caption of the photo is quite misleading to mention the Mediterranean! The Bosporus is the strait connecting the Black Sea to the Sea of Marmara as the article text rightly says. Adding the Mediterranean includes the Dardenelles.

john Wilson wrote: 11-16-2010 13:28:49

Good Info, If it is high risk to pass the Bosporus. International Shipping Companies should go up to marmara sea and pass the Black sea via Land