Climate change and terrestrial wildlife management in the Alaskan Arctic

This is Section 11.3.4 of the Arctic Climate Impact Assessment

Lead Author: David R. Klein; Contributing Authors: Leonid M. Baskin, Lyudmila S. Bogoslovskaya, Kjell Danell, Anne Gunn, David B. Irons, Gary P. Kofinas, Kit M. Kovacs, Margarita Magomedova, Rosa H. Meehan, Don E. Russell, Patrick Valkenburg

The management system for terrestrial wildlife in Alaska that developed following its admission to statehood in 1959 initially followed the institutional structures adopted by most other states. In both the United States and Canada, wildlife has been considered by law common property of the people and therefore control of its use, management, and conservation has fallen within the jurisdiction of the state or province within which it occurred. This is in contrast to the system throughout most of Europe where wildlife is the property of the landowner. With the settlement of claims of indigenous peoples in the Canadian North, however, varying levels of responsibility for management of wildlife have been granted to regional indigenous governing authorities. The federal governments of the United States and Canada hold jurisdiction over migratory birds and interstate or inter-province traffic in harvested wildlife.

In Alaska, a Board of Game, comprising residents of the state appointed by the Governor, establishes regulations governing wildlife harvesting. Regulations established by the board are based on recommendations from professional biologists and managers employed by the Alaska Department of Fish and Game in collaboration with biologists of federal land management agencies, as well as on recommendations from regional citizens advisory groups, and the general public, within the constraints of laws passed by the State Legislature governing wildlife conservation and use. Administrative structure for wildlife management in the State of Alaska mirrors that of other states. Actual wildlife management in Alaska, however, now differs markedly from the other states with similar involvement of the public in resource management decision-making. In Alaska, the federal government, primarily through the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, assumes a much greater role in regulation of the harvest of wildlife than in other states. This federal participation in the wildlife regulatory process came about through legislation resulting from settlement of the land claims of the indigenous peoples of Alaska and related legislation by the U.S. Congress (the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act of 1971 and the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act of 1980). These federal laws mandate that rural residents of Alaska, comprised mostly of indigenous peoples, should receive priority over urban and non-resident hunters in harvesting for subsistence use of the annual surplus of fish and wildlife from federal lands. The state’s failure to pass similar subsistence priority legislation, consistent with the state constitution, resulted in the loss of management authority by the state for fish and wildlife on federal lands in Alaska. Since federal lands in national forests, wildlife refuges, national parks, military and other federal reserves, and federal public domain lands constitute 60% of the total land area of Alaska (1.48 million square-kilometers (km2)), the federal role in management and conservation of wildlife in Alaska is unique among the states. This federal–state partnership in management of Alaska’s fish and wildlife resources has been both controversial and complex and has contributed to political polarization between urban and rural users of fish and wildlife resources[1]. However, in most regions of the Alaskan Arctic sufficiently remote from urban centers there is little competition in the harvest of wildlife between the mainly indigenous, rural population and urban hunters, although hunting methods and especially means of transport have changed markedly in recent decades.

In spite of the legal complexities involved in managing Alaska’s wildlife, state and federal wildlife biologists and managers increasingly are working together with users toward maintaining sustainable harvests of wildlife, achieving equitable allocation of the harvest among wildlife users, and improving efficiency of the management process. Biologists and managers with the Alaska Department of Fish and Game, involved with management of caribouof the Western Arctic Herd, Alaska’s largest caribou herd estimated to contain 490,000 animals in 2003, have been instrumental in establishing a Western Arctic Caribou Herd Working Group whose members represent indigenous and non-indigenous hunters, federal land management agencies, state resource management agencies, and environmental organizations. This working group is viewed as a preliminary step in the process of establishing a multi-stakeholder system for the Western Arctic Herd in which users play an important role in the management process similar to the Canadian co-management boards for the Beverly and Qamanirjuaq and Porcupine caribou herds[2].

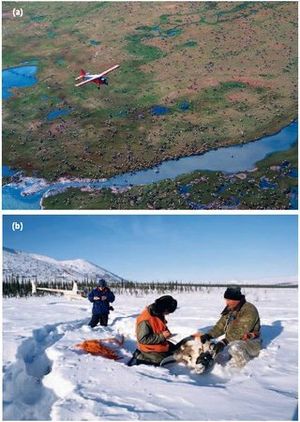

Management of wildlife in the arctic regions of Alaskaalso differs from wildlife management as traditionally practiced in most of the United States in that natural plant communities that constitute wildlife habitat have undergone little alteration through conversion of the land for agriculture, intensive forest management, industrial development, and urban sprawl. As a consequence, the focus of wildlife management in the Alaskan Arcticby state and federal wildlife biologists has largely been on monitoring structure and harvest levels of the most important hunted and trapped wildlife species rather than on aspects of habitat manipulation or restoration. Population estimates and condition and trend information are collected on caribou, moose, muskoxen, and mountain sheep largely through aerial surveys, facilitated through limited use of radio transmitters placed on some animals in more intensively monitored populations (Fig. 11.6). Similar, but less intensive survey work is also focused on wolves and brown bears as a basis for assessing their potential influence on ungulate populations through predation. This survey information is increasingly being supplemented by harvest information obtained from hunters for development of annual recommendations of harvest levels that are made to the Alaska Board of Game and the Federal Subsistence Division. The status and trends in populations of wild mammals in the arctic regions of Alaska that are hunted and trapped, their harvest levels, and possible threats to their populations are shown in Table 1.

|

Table 1. Status and trends in major land-based wildlife species in the Alaskan Arctic (based on data for 2003 from the Alaska Department of Fish and Game). | ||||

|

Population statusa(number per estimate) |

Trend |

Harvest levelb |

Threat | |

| Caribou (by herd) | ||||

| Western Arctic | 430,000 | down | 22,000 | weather, coal miningc |

| Porcupine Herd | 125,000 | down | 4,500 | oil development |

| Central Arctic | 27,000 | stable | 1,100 | oil development |

| Teshekpuk | 27,000 | stable | 3,000 | oil development |

| Mulchatna | 130,000 | down | 6,000 | diseased |

| Nushagak | 1,500 | stable | 300 | no immediate threats |

| Northern Peninsula | 7,000 | stable | 500 | diseased |

| Southern Peninsula | 3,500 | up | 100 | no immediate threats |

| Adak Island | 1,500 | up | 200 | no immediate threats |

| Muskox | ||||

| North Slope | 1,000 | stable | 40 | illegal harvest |

| Seward Peninsula | 800 | up | 50 | no immediate threats |

| Nunivak Island | 500 | stable | 75 | no immediate threats |

| Nelson Island | 230 | stable | 25 | illegal harvest |

| Moose | ||||

| North Slope | 750 | up | 30 | diseasee |

| Selawik/Kobuk/Noatak | 10,000 | stable | 400 | no immediate threats |

| Seward Peninsula | 5,000 | stable | 350 | no immediate threats |

| Yukon/Kuskokwim | 3,000 | up | 200 | illegal harvestf |

| Northern Bristol Bay | 3,500 | up | 600 | no immediate threats |

| Alaska Peninsula | 5,000 | stable | 300 | no immediate threats |

| Brown bear | ||||

| North Slope | 2,000 | up | 40 | no immediate threats |

| Selawik/Kobuk/Noatak | 3,000 | up | 40 | no immediate threats |

| Seward Peninsula | 1,250 | up | 75 | illegal harvestg |

| Yukon/Kuskokwim | 750 | up | 25 | no immediate threats |

| Northern Bristol Bay | 1,500 | up | 75 | no immediate threats |

| Alaska Peninsula | 8,500 | up | 300 | no immediate threats |

| Wolf | ||||

| Wolf numbers in coastal areas of Alaska vary widely from year to year because wolves are susceptible to rabies that is periodically enzootic in Arctic foxes. Wolves are probably more common now than at any time over the last 100 years because of the relatively high numbers of moose and caribou that now occur. Wolf densities are higher in the more forested areas where they also can prey on moose. In some local areas (e.g., the North Slope and Seward Peninsula) wolf numbers are below natural levels due to legal and illegal harvest. There are no foreseeable human-related threats to wolves, except on the Seward Peninsula where reindeer herders attempt to exclude them from reindeer grazing areas | ||||

| Black bear | ||||

| Black bears are abundant in the Kobuk Valley, Yukon Flats, and in most other forested areas, but the Alaskan Arctic is the periphery of black bear range, so they are absent or rare from most arctic areas. Numbers of black bears will probably increase as forest cover expands in northwest Alaska. There are no foreseeable human-related threats to black bears | ||||

| Wolverine | ||||

| Wolverines are common throughout the Alaskan Arctic, and with the worldwide decline in fur prices, interest in harvesting them has decreased. Wolves commonly kill wolverines and wolverine densities appear to be higher in areas where wolf numbers are low. There are no foreseeable human-related threats to wolverines | ||||

| Lynx | ||||

| Lynx are cyclic or irruptive in the Alaskan Arctic, and in areas where snowshoe hares become periodically abundant, lynx can become abundant. Lynx are virtually absent from most areas in most years | ||||

| Other fur-bearers | ||||

| Other common fur-bearers in the Alaskan Arctic are mink, river otter, marten, red fox, and Arctic fox, although all of these except red and Arctic foxes are uncommon on Alaska’s North Slope | ||||

| aPopulation estimates are based on the most recent census or survey. For some species (e.g., brown bears) data are extrapolated from intensively surveyed areas to larger areas; bEstimates adjusted annually based on subsistence harvest surveys. About 85% of the caribou harvest is by local residents. About 50% of moose and brown bears harvested is by local residents. Almost 100% of the harvest of black bears and fur-bearers is by local residents; cMost Western Arctic caribou winter in a relatively small area where food could become inaccessible due to unusual and extreme coastal snowstorms and icing. The calving area contains about 50% of the known U.S. coal reserves, but these reserves are unlikely to be developed within the next 50 years; dPneumonia has been prevalent as these caribou herds have declined from high population levels; eMoose are recovering from a long-term decline that was possibly related to Brucellosis; fMoose, especially in the Kuskokwim River drainage area, are illegally harvested at a rate that prevents population expansion into suitable habitat on the lower reaches of the river; gBrown bears are heavily hunted (legally and illegally) in areas with reindeer herding | ||||

[[Image:320px-Figure11.7_fires_in_arctic.JPG|thumb|Fig. 11.7. The increasing frequency of fires and total area burned in the northern forest zones and in the ecotone between forest and tundra (see [[Arctic Climate Impact Assessment] (ACIA), Chapter 14]), a consequence of climate warming, poses difficult decisions for wildlife managers. Although fire has been a natural feature of the ecology of these plant communities, a reduction in the ratio of older plant communities with high lichen biomass to post-fire early succession stages can be detrimental to caribou and reindeer that feed on the lichens in winter. The shrubs that are characteristic of the post-fire vegetation are also favored by recent climate warming, and provide suitable forage for moose. More intensive efforts at fire suppression may benefit caribou and reindeer, at least in the short term, to the detriment of moose. (Source: ACIA)]]

Focus on the population dynamics of wildlife is a relatively efficient and cost-effective approach to management of wildlife. However, without inventory and monitoring of vegetation, its quality, and availability as forage within the [[habitat]s] of large herbivores (Herbivory), knowledge of vegetation changes brought about through climate change, wildfire, or other factors cannot be integrated into the management and conservation of wildlife. The recent and expected continuing increase in area burned by wildfires in the ecotone between the boreal forest and the arctic tundra is of special relevance. This is because much of the lichen-dominated winter range of the large migratory herds of caribou in Alaskalies within this ecotone[3] (Fig. 11.7). Thus the adaptability of management to respond to the effects of climate change is substantially limited.

Minimizing impacts of industrial development on wildlife and their habitats (11.3.4.1)

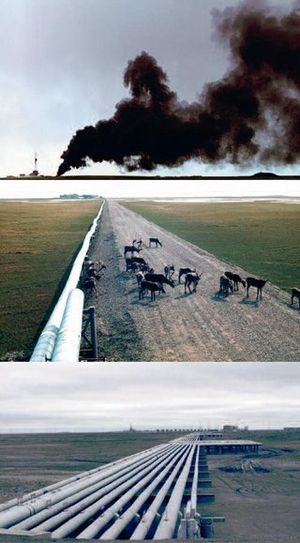

Increasingly, industrial development activities associated with energy and mineral exploration and extraction in the Alaskan Arcticare encroaching on wildlife [[habitat]s] and threatening wildlife populations through habitat loss, expanded legal and illegal wildlife harvest, and environmental contamination from industrial pollutants entering wildlife food chains. Assessing the magnitude and importance of impacts from existing and proposed industrial development activities in the Arctic is a time-consuming and difficult process under the best of circumstances. This task is rendered even more difficult when the ongoing effects on the environment of accelerated climate change in the Arctic must be factored into the assessment. Although an environmental impact assessment is required under the National Environmental Policy Act of 1969 as a basis for seeking approval for any large-scale federal project "significantly affecting the quality of the human environment", there has been relatively little effort made to undertake follow-up assessments of the actual impacts of projects once they have been approved. The assessments that have been made of the magnitude and ecological significance of threats resulting from specific development projects have been simple, general overviews[4], or have focused on specific wildlife species[5], or have been limited to a few specific impacts or types of projects[6]. Assessment of the consequences of cumulative impacts from multiple interrelated projects taking place over extended periods has only recently been attempted through analysis and synthesis of past studies. The most recent and comprehensive effort in this regard was the Assessment of the cumulative effects of petroleum development on Alaska’s North Slope that was compiled by a panel of experts appointed through the National Research Council, with a primary focus on the giant Prudhoe Bay and related oil fields[7]. Investigative assessment of the environmental consequences of development projects can provide valuable information for the government bodies responsible for weighing the potential consequences of proposed new development projects.

In most of the Alaskan Arctic there is insufficient knowledge of plant and animal distributions on the lands and in the waters, and the ecological relationships existing there, as a basis for carrying out environmental impact assessments in advance of proposed development projects. Short-term studies specifically designed to address postulated impacts on wildlife and their habitats in the absence of an understanding of the complexity of the ecosystem relationships that may be affected are usually inadequate to enable a comprehensive assessment of the environmental impacts that may result from a project. An exception was the proposal to drill for oil in the coastal plain of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge in northeastern Alaska resulting in the debate before the U.S. Congress in spring 2002. In that case, the background of 20 years of detailed environmental studies of the proposed development area, including mapping of the vegetation and multi-year investigation of the population dynamics and ecosystem relationships of wildlife species, enabled a comprehensive assessment of the expected impacts of the proposed oil development[8]. As a consequence, information about the wildlife and other environmental values and the magnitude of the risks to which they would be exposed should oil development be allowed there played a major role in Congress’ unwillingness to open the Arctic Refuge to oil development. Assessment of the impacts of proposed industrial development on the ecosystems of the Arctic Refuge was compounded by the difficulty of distinguishing between ecosystem-level effects resulting from climate change influences versus those resulting from the proposed development (Fig. 11.8).

A major obstacle to effective wildlife management in the Arcticin the face of increasing national and global pressures for large-scale energy and mineral extraction is the lack of specific information at the landscape level of wildlife distribution, habitat types and their seasonal use patterns, definition and mapping of critical habitats, and mapping of human land use and related wildlife harvests. An ultimate goal for effective management and conservation of wildlife and wildlife habitats in the Alaskan Arctic, as well as for all regions of the Arctic, is the accumulation of sufficient knowledge of the wildlife and other resources of the lands and waters to enable development of detailed regional land and water use plans. Such plans should employ the use of technology for remote sensing of landscape characteristics and Geographic Information Systems (GIS) maps, and include analysis of plant community and soil characteristics, determination of wildlife and fish distribution, identification of critical fish and wildlife habitats, and designation of existing and proposed protected areas. An important part of regional land and water use plans, as the name implies, is mapping of existing patterns of land and water use for subsistence and other human activities, and other physical and biological features of the environment. This documentation of the physical and biological characteristics of the lands and waters of arctic regions would provide a basis for identifying and contrasting changes that may occur in the environment as a consequence of climate change. Its primary value, however, would be in assisting industrial interests in advance planning of development activities in the Arctic to minimize their potential impact on fish and wildlife resources and the users of these resources, and in the evaluation and assessment of proposed industrial developments by local, regional, and national governing bodies prior to their decisions over approval. Details of development of regional land and water use plans and use of environmental impact statements and environmental impact assessments as the basis for land and water use decisions in relation to wildlife management and conservation in northern ecosystems were described by Klein and Magomedova[9] from which the text

in Box 11.4 is abstracted.

|

Box 11.4.The potential role of regional land and water use planning in wildlife management and conservation in the Arctic Components of ecosystem planning

Value and use of the land and water use plan

Climate change as a factor in assessing industrial impacts

|

Chapter 11. Management and Conservation of Wildlife in a Changing Arctic Environment

11.1 Introduction (Climate change and terrestrial wildlife management in the Alaskan Arctic)

11.2 Management and conservation of wildlife in the Arctic

11.3 Climate change and terrestrial wildlife management

11.3.1 Russian Arctic and sub-Arctic

11.3.2 The Canadian North

11.3.3 The Fennoscandian North

11.3.4 The Alaskan Arctic

11.4 Management and conservation of marine mammals and seabirds in the Arctic

11.5 Critical elements of wildlife management in an Arctic undergoing change

References

Citation

Committee, I. (2012). Climate change and terrestrial wildlife management in the Alaskan Arctic. Retrieved from http://editors.eol.org/eoearth/wiki/Climate_change_and_terrestrial_wildlife_management_in_the_Alaskan_Arctic- ↑ Klein, D.R., 2002. Perspectives on wilderness in the Arctic. In: A. Watson, L. Alessa and J. Sproull (eds.). Wilderness in the Circumpolar North: Searching for Compatibility in Ecological, Traditional, and Ecotourism Values, pp. 1–6. 2001 May 15–16; Anchorage, Alaska.

- ↑ Klein, D.R., L. Moorhead, J. Kruse and S.R. Braund, 1999. Contrasts in use and perceptions of biological data for caribou management. Wildlife Society Bulletin, 27:488–498.– Thomas, D.C. and J. Schaefer, 1991. Wildlife co-management defined: The Beverley and Kamanuruak Caribou Management Board. Proceedings of the Fifth North American Caribou Workshop. Rangifer, Special Issue 7:73–89.

- ↑ Weladji, R., D.R. Klein, Ø. Holand and A. Mysterud, 2002. Comparative response of Rangifer tarandus and other northern ungulates to climatic variability. Rangifer, 22:33–50.

- ↑ Klein, D.R., 1973. The impact of oil development in the northern environment. Proceedings of the 3rd Interpetrol Congress, Rome, Petrolio e ambiente, pp. 109–121.–Klein, D.R., 1979. The Alaska Oil Pipeline in retrospect. Transactions of the North American Wildlife and Natural Resources Conference, 44:235–246.

- ↑ Cameron, R.D., W.T. Smith, R.G. White and B. Griffith, 2002. The Central Arctic Caribou Herd. In: D.C. Douglas, P.E. Reynolds and E.B. Rhode (eds.). Arctic Refuge Coastal Plain Terrestrial Wildlife Research Summaries, pp. 38–45. U.S. Geological Survey, Biological Resources Division, Biological Science Report USGS/BRD/BSR-2002-0001.

- ↑ Douglas, D.C., P.E. Reynolds and E.B. Rhode (eds.), 2002. Arctic Refuge Coastal Plain Terrestrial Wildlife Research Summaries. U.S. Geological Survey, Biological Resources Division, Biological Science Report USGS/BRD/BSR-2002-0001.

- ↑ NRC, 2003. Assessment of the cumulative effects of petroleum development on Alaska's North Slope. National Academy Press, xiii + 452pp.

- ↑ Douglas, D.C., P.E. Reynolds and E.B. Rhode (eds.), 2002. Arctic Refuge Coastal Plain Terrestrial Wildlife Research Summaries. U.S. Geological Survey, Biological Resources Division, Biological Science Report USGS/BRD/BSR-2002-0001.

- ↑ Klein, D.R. and M. Magomedova, 2003. Industrial development and wildlife in arctic ecosystems: can learning from the past lead to a brighter future? In: R.O. Rasmussen and N.E. Koroleva (eds.). Social and Economic Impacts in the North, pp. 35–56. Kluwer Academic.