Western Indian Ocean Islands and the atmosphere

One of the most important assets for the Western Indian Ocean (WIO) states is its climate, which supports the evolution of a wide diversity of ecosystems and helps to promote socioeconomic activities such as agriculture, fisheries and tourism. This favourable climate is at risk, however, from external and internal stresses. The sub-region is already experiencing the negative impacts of global warming. Although the emission of green house gases (GHG) is small, industrialization and urbanization are contributing to deterioration of the state of the atmosphere. Many of these effects are long-term, and possibly irreversible, with adverse social and economic consequences. Climate variation affects the potential to attract tourists, the capacity for agriculture and the propensity for disease.

Madagascar experiences serious periods of both drought and torrential rain. The high humidity, coupled with large areas of stagnant floodwater in the summer months, can promote malaria. Malaria, once endemic in Mauritius, has now been eradicated by a sustained, integrated programme of prevention, early detection and effective treatment.

All WIO countries suffer from water scarcity and this is exacerbated by the increasing demand from agriculture and tourism, particularly in Mauritius and the Seychelles.

The high percentage of warm and wet days in Mauritius has proved well-suited to the production of sugar cane. September, October and November have the lowest rainfall, fewest wet days and a temperature range more comfortable for the European tourists.

Two important climate systems affecting the WIO islands are the Inter-Tropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) and the Indian Ocean Dipole. The ITCZ, which is the breeding ground for tropical cyclones, also gives rise to heavy rainfall over the Seychelles during the summer months (November to April) when it oscillates around the latitude of 8°S. In March 2005, the Mascarene Islands experienced record rainfall as the ITCZ oscillated much further south for days, causing widespread flooding and accumulation of water with increased mosquito breeding and sanitation problems. When the Indian Ocean Dipole occurs at the same time as the El Niño/Souther Oscillation (ENSO) event, changes are produced in the patterns of circulation of the air and sea across the Indian Ocean, affecting temperature and rainfall across the sub-region. However, further studies are necessary to confirm the nature and extent of the impact of these phenomena on cyclone formation and climate generally. The ENSO is predicted to become more frequent with global climate change, and expected to cause important disruption in coastal processes. Coral bleaching events may become more frequent and severe, as the climate continues to warm, exposing coral reefs to an increasingly hostile environment. In the 1997-98 El Niño event, coral reefs in the Indian Ocean suffered extensive and severe bleaching.

There are widespread socioeconomic impacts of abnormal weather. Records show that in the period 1951-2004, windstorms accounted for 80 percent of the deaths from natural disasters. Although the Seychelles lie outside the cyclone belt, these islands are experiencing an increasing frequency and intensity of storms. In August 1997, extreme rainfall conditions led to floods and landslides causing damage to more than 500 houses and almost 40 percent of public roads. A similar event in September 2002 hit the island of Praslin, the second largest island in the Seychelles, destroying over 25,000 trees, and causing damage to housing and infrastructure with a total estimated loss of US$87 million.

The future likely impacts of climate change and sea-level rise in the WIO countries include coastal erosion, droughts, coral bleaching, more mosquitoborne disease, saline intrusion into water sources, flooding, storm surges, and greater water scarcity in the face of increasing demand. October 2004 was the warmest month of the year recorded in the WIO countries since the industrial revolution. This followed October 2003 which was the warmest October ever recorded in Mauritius. Building resilience against climate change requires establishing special funds and making new investments.

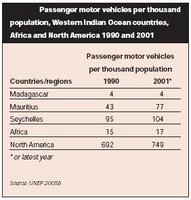

The prevalence of passenger motor vehicles and CO2 emissions are rising steadily in the more developed of the WIO countries, and at much higher rates than for Africa as a whole. Whilst these levels remain substantially below those reported for North America, the trend presents a growing threat to both livelihoods and to health, in terms of road congestion, increasing travel times, higher transport costs and air pollution.

The WIO countries have established environmental programmes and developed policies to integrate climate-related concerns in their political agendas. All WIO countries have submitted their first National Communication within the framework of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change UNFCCC, and some are in the process of preparing their second National Communication.

Initiatives to reduce air pollution and promote greater efficiency in energy generation and use require a variety of educational and other measures in the public and the private sector. These include the promotion of low energy lighting, photovoltaic systems, solar water heating and solar wood drying kilns for timber treatment for construction, liquid propane gas (LPG) cookers for domestic cooking, solar street lighting, methane gas for energy production, ethanol as a partial fuel substitute, sugar cane bagasse for energy production, and wind-generated energy in, for example, Mauritius’ outer island of Rodrigues. But these initiatives, with the exception of the use of bagasse, have yet to be developed as major programmes which benefit from standardization and economies of scale, in any of the countries. Both wind and solar equipment have to be made more robust against cyclone damage. Moreover, the public sector has yet to show a coherent, environmentally friendly approach to energy efficiency in the provision of its own services and in public contracts in building designs and materials for schools, hospitals and public sector housing.

Further reading

- IRIN, 2005. Senegal: Climate change impacting hard on semi-arid Sahel nations. Integrated Regional Information Networks.

- L’Hôte,Y., Mahé, G., Somé, B. and Triboulet, J., 2002. Analysis of a Sahelian annual rainfall index from 1896 to 2000; the drought continues. Hydrological Sciences, 47 (4), 563-72.

- UNEP, 2006. Africa Environment Outlook 2

|

|

| Disclaimer: This article is taken wholly from, or contains information that was originally published by, the United Nations Environment Programme. Topic editors and authors for the Encyclopedia of Earth may have edited its content or added new information. The use of information from the United Nations Environment Programme should not be construed as support for or endorsement by that organization for any new information added by EoE personnel, or for any editing of the original content. |