Water profile of Tanzania

Contents

- 1 Geography, Climate, and Population

- 2 Economy, Agriculture, and Food security

- 3 Water Resources and Use

- 4 Irrigation and Drainage Development

- 5 Water Management, Policies, and Legislation Related to Water Use in Agriculture

- 6 Environment and Health

- 7 Perspectives for Agricultural Water Management

- 8 Further Reading

Geography, Climate, and Population

The United Republic of Tanzania (6°00' South, 35°00' East) consists of the mainland and Zanzibar, which is made up of the islands Unguja and Pemba. Its total area is 945,090 square kilometers (km2). The country is bordered in the north by Kenya and Uganda, in the east by the Indian Ocean, in the south by Mozambique and in the west by Rwanda, Burundi, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and Zambia. The Indian Ocean coast is some 1,300 kilometers (km) long, while in the northwest there are 1,420 km of shoreline on Lake Victoria, in the center-west there are 650 km of shoreline on Lake Tanganyika, and, in the southwest, 305 km of shoreline on Lake Malawi.

The terrain comprises plains along the coast, a plateau in the central area, and highlands in the north and south. The northeast border with Kenya is dominated by Mt. Meru and Mt. Kilimanjaro. Southwards is the Central Plateau reaching elevations above 2,000 meters (m). The mountain range of the Southern Highlands separates the Eastern plateau from the rest of the country.

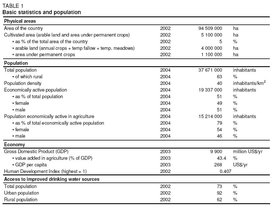

Land-cover is dominated by woodland, grassland, and bushland which account for about 80 percent of the total land area. Cultivable area is estimated to be 40 million hectares (ha), or 42 percent of the total land area. In 2002, 13 percent of the cultivable area was actually cultivated, comprising 4 million ha of arable land and 1.1 million ha under permanent crops (Table 1).

The climate varies from tropical along the coast to temperate in the highlands. There are two types of seasonal rainfall distribution:

- The unimodal type, where rainfall is usually from October/November to April, found in the central, southern and southwestern highlands

- The bimodal type, comprising two seasons: the short rains (Vuli) fall from October to December, while the long rains (Masika) fall from March to June. This type occurs in the coastal belt, the northeastern highlands and the Lake Victoria Basin.

Annual rainfall varies from 500 millimeters (mm) to 1,000 mm over most of the country. The highest rainfall of 1,000 mm to 3,000 mm occurs in the northeast of the Lake Tanganyika basin and in the Southern Highlands. Mean annual rainfall is 1,071 mm. Zanzibar and the coastal areas are hot and humid and average daily temperatures are around 30°C. October-March is the hottest period. Sea breezes however temper the region’s climate and June-September is coolest with temperatures falling to 25°C. In the Kilimanjaro area, temperatures vary from 15°C in May-August to 22°C in December-March.

The total population is 37.7 million (2004), of which 63 percent is rural (Table 1). The population density is 40 inhabitants/km2. The vast majority of the population lives inland, far away from the [[coast]line]. Poverty is concentrated in the rural areas; however, urban poverty has accompanied rapid urbanization. The national poverty rate is about 36 percent. In 2002, 92 percent of the urban and 62 percent of the rural population were using improved drinking water sources (Table 1).

Economy, Agriculture, and Food security

The country’s gross domestic product (GDP) was US$9.9 billion in 2003, and the value added in agriculture was 43.4 percent of GDP. The agricultural sector continues to lead economic growth, in spite of the recent emergence of the new high-growth sectors of mining and tourism, and it continues to have the highest impact on the levels of overall economic growth. Agriculture provides work for 14.7 million people, or 79 percent of the total economically active population, and 54 percent of agricultural workers are female. Small-scale subsistence farmers comprise more than 90 percent of the farming population, with medium- and large-scale farmers accounting for the rest.

The main food crops grown are maize, sorghum, millet, paddy, wheat, sweet potato, cassava, pulses, and bananas. Maize is the dominant crop with a planted area of over 1.5 million hectares (ha) during recent years, followed by paddy with more than 0.5 million ha over recent years. The main agricultural products exported by the United Republic of Tanzania are green coffee, cashew nuts, and tobacco that, in 2001, represented about 41 percent of all agricultural exports. The main agricultural products imported are wheat and palm oil.

In recent years, the country has not been self-sufficient in cereals, but it is self-sufficient in non-cereals at the national level. However, there is a clear difference in the supply capabilities of staple-food crops among the regions:

- In Arusha, Coast, Dar es Salaam, Dodoma, Kigoma, Kilimanjaro, Mara, Tabora and Tanga, the supply is constantly less than demand;

- Iringa, Mbeya, Mwanza, Rukwa, Ruvuma and Shinyanga have attained self-sufficiency or produce surpluses.

Rainfed cropping systems can be classified into three broad categories:

- Short rains (Vuli) season from September/October to January/February;

- Long rains (Masika) season from February/March to June/July;

- A combination of the two (Musumi) from November to June.

Water Resources and Use

Water Resources

Tanzania has nine major drainage basins that, according to the recipient water body, can be categorized as follows:

Draining to the Mediterranean Sea:

- The Lake Victoria basin, which is part of the Nile River basin.

Draining to the Indian Ocean:

- The Pangani River basin;

- The Ruvu/Wami River basin;

- The Rufiji River basin;

- The Ruvuma River and Southern Coast basin;

- The Lake Nyasa (Lake Malawi) basin, which is part of the Zambezi River basin;

Draining to the Atlantic Ocean:

- The Lake Tanganyika basin, which is part of the Congo River basin.

Rift Valley (endorheic) basins, of which amongst others:

- The Lake Eyasi and Bubu depression; Lake Manyara;

- The Lake Rukwa basin.

River regimes follow the general rainfall pattern. River discharge and lake levels start rising in November-December and generally reach their maximum in March-April with a recession period from May to October/November. Many of the larger rivers have flood plains, which extend far inland with grassy marshes, flooded forests, and ox-bow lakes.

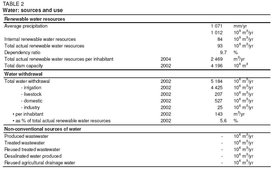

Total renewable water resources amount to 93 cubic kilometers per year (km3/yr) (Table 2), of which 84 km3/yr are internally produced and 9 km3/yr are accounted for by the Ruvuma River, which flows on the border between Tanzania and Mozambique. Renewable groundwater resources are estimated at 30 km3/yr, of which all but 4 km3/yr are considered to be overlap between surface water and groundwater.

About 5.7 percent of the total land area of the United Republic of Tanzania is covered by three lakes, which also form the border to neighboring countries:

- Lake Victoria, which is part of the Nile River basin, is shared with Kenya and Uganda. Its total area is 68,800 km2, of which 51 percent belong to the United Republic of Tanzania.

- Lake Tanganyika, which is part of the Congo River basin, is shared with Burundi, Democratic Republic of Congo, and Zambia. Its total area is 32,900 km2, of which 41 percent belong to the United Republic of Tanzania.

- Lake Nyasa or Lake Malawi, which is part of the Zambezi River basin, is shared with Malawi and Mozambique. Its total area is 30,800 km2, of which the United Republic of Tanzania claims 5,569 km2 or 18 percent.

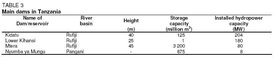

Other lakes include Lake Rukwa, Lake Eyasi, Lake Manyara, Lake Natron, Lake Balangida. The main dams in the United Republic of Tanzania are given in Table 3.

In the 1970s, 21 small-scale earthfill-type dams were constructed mainly on seasonal rivers in the Tabora region for irrigation and domestic supply purposes. All except seven of them suffer from serious sedimentation. In addition to these dams, there are many smaller dams over the whole land, called Charco dams, for irrigation, domestic, and livestock purposes. In general, dam construction is largely restricted by hydrological and topographic conditions.

Water Use

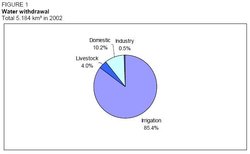

Total water withdrawal in mainland Tanzania was estimated for the year 2002 to be 5,142 million cubic meters (m3) (Table 3). Agriculture consumes the largest share with 4,624 million m3 (almost 90 percent of total) of which 4,417 million m3 for irrigation and 207 million m3 for livestock, while the domestic sector uses 493 million m3. Total water withdrawal by the domestic sector and irrigation in Zanzibar is estimated to be about 42 million m3. Of this, withdrawal on Unguja Island is 33 million m3 and on Pemba Island it is 9 million m3. Industry in Tanzania consumes an estimated 25 million m3 (Figure 1).

International Water Issues

The United Republic of Tanzania shares three major lakes (Lake Victoria, Lake Tanganyika, and Lake Nyasa (Malawi)) with neighbouring countries, as well as Ruvuma River on the border with Mozambique.

Since Lake Victoria is part of the Nile River basin, the United Republic of Tanzania is one of the member countries of the Nile Basin Initiative, which was officially launched in February 1999 in Dar es Salaam, following an agreement of the Ministers of Water Affairs of the Nile Basin States.

The Kagera River basin covers the upper part of the Nile Basin until its entry into Lake Victoria and involves Burundi, Rwanda, the United Republic of Tanzania, and Uganda. The Kagera Basin Organization (KBO) (defunct in 2004) was set up as the organization for the management and development of the Kagera River basin. The objective of the KBO was to deal with all questions concerning the activities to be carried out in the Kagera River basin. In addition, an agreement to manage Lake Victoria has been signed by the countries of the East African Community and programs to implement the agreement are being studied.

At the bilateral level, the United Republic of Tanzania is implementing a project on the stabilization of the Songwe River course jointly with Malawi, through the Malawi/Tanzania Joint Permanent Commission of Cooperation (JPCC).

The United Republic of Tanzania, together with Angola, Burundi, Cameroon, the Central African Republic, the Congo, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Rwanda, and Zambia, shares the Congo (Zaïre) River; and in the Zambezi River Basin with Angola, Botswana, Malawi, Mozambique, Namibia, Zambia, and Zimbabwe. The Zambezi Watercourse Commission (ZAMCOM) was created in 2004 between the eight countries sharing the basin.

Irrigation and Drainage Development

Evolution of Irrigation Development

Irrigation potential is estimated by the 2002 Study on the National Irrigation Master Plan (NIMP) to be 2,123,700 ha in mainland Tanzania, while for Zanzibar it is estimated to be 8,521 ha. The criteria for this estimate are water resources potential, land resources potential, and socio-economic potential. The high potential areas are located in roughly four locations:

- Mara, Mwanza and Kagera regions

- Arusha and Kilimanjaro regions

- Morogoro region

- Mbeya and Iringa regions

Irrigation in the form of traditional irrigation schemes goes back hundreds of years in the country. Those schemes have however become inadequate as a result of an increase in population, wear and tear, catchment degradation, etc. The response to the increasing shortcomings of these schemes from colonial times until recently has largely been:

- the construction of new irrigation estates for parastatal organizations

- the construction of new modern-style schemes to be run by smallholders

- the rehabilitation or upgrading of traditional irrigation schemes

However, the great majority of those schemes have had very limited success and the only successful ones are in the private sector. In general, the development of irrigated agriculture in the United Republic of Tanzania has been slow, for reasons such as:

- the absence of vital irrigation data for planning purposes

- a lack of resources on the part of the government (funds and trained irrigation personnel)

- the absence of national irrigation investment criteria

- the lack of any national coordination of irrigation development, despite available funding from donors

According to the NIMP, the total area equipped for irrigation is 184,330 ha, of which 183,988 ha in mainland Tanzania and 342 ha in Zanzibar (Table 4). The NIMP had inventoried 1,428 irrigation schemes (including water harvesting schemes) in mainland Tanzania, of which 29 were being implemented, 79 did not need rehabilitation, and 37 had been rehabilitated within the last five years. The rest, about 90 percent of all schemes, needed some form of rehabilitation. In Zanzibar, 19 irrigation schemes were inventoried. Rainwater harvesting schemes cover 7,934 ha in mainland Tanzania, mainly located in the regions of Dodoma, Mara, Mwanza, Shinyanga, Singida, and Tabora. In these schemes, runoff is diverted from residential areas, paths, and transient streams to fields in the bottom of the valleys, where mainly paddy rice is grown. The most important system is the diversion of ephemeral streams for distances up to 2 km.

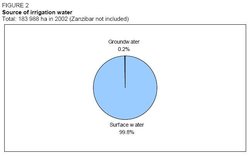

Most of the irrigated areas are under surface irrigation, mainly used by smallholders. Water distribution is usually by lined and unlined canals, and furrows and basins are widely used. Sprinkler irrigation is used by few large-scale commercial farmers. It is not common amongst smallholders. Drip irrigation is rarely used. Almost all irrigation water on the mainland is surface water, and groundwater is utilized on only 0.2 percent of all irrigated areas (Figure 2).

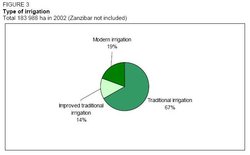

The following types of irrigation schemes are distinguished in the United Republic of Tanzania (Figure 3):

- Modern irrigation schemes (35,847 ha): these are formally planned and designed schemes with full irrigation facilities and usually a strong element of management by the government or other external agencies. Those schemes are developed in the regions of Kilimanjaro, Morogoro, and Mbeya. All parastatal managed irrigation schemes also fall under this category.

- Traditional irrigation schemes (122,630 ha): these have been initiated and operated by the farmers themselves, with no intervention from external agencies. They include schemes based on traditional furrow irrigation for the production of fruit and vegetables in the highlands and simple water diversion schemes on the lowland for paddies.

- Improved traditional irrigation schemes (25 511 ha): these are traditional irrigation schemes on which, at some stage, there was intervention by an external agency, such as the construction of a new diversion structure.

- Water harvesting schemes: water harvesting and flood recession schemes, on which sub-subsistence farmers have introduced simple techniques to artificially control the availability of water to the crops.

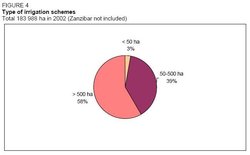

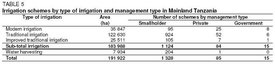

Of the 1,428 irrigation schemes inventoried by the NIMP, 1,328 were smallholder schemes, 85 private schemes and 15 government-managed schemes. About 3 percent of the total area is covered by small schemes with an area of less than 50 ha each, while 58 percent is covered by schemes of over 500 ha each (Table 5 and Figure 4).

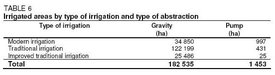

Gravity-fed irrigation schemes account for over 99 percent of the irrigated area, while the rest uses pumps for water abstraction (Table 6 and Figure 5). The latter schemes are mainly located in the regions of Kagera, Mara. and Mwanza.

Role of Irrigation in Agricultural Production, the Economy, and Society

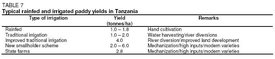

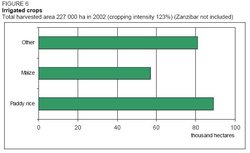

The main irrigated crops are paddy rice and maize, accounting for about 48 percent and 31 percent of the irrigated areas in 2002 (Table 4 and Figure 6). Other irrigated crops account for 44 percent of the irrigated areas and comprise beans, vegetables (including onion, tomato, and leaf vegetables), bananas, and cotton. From the above figures, the cropping intensity is 123 percent. Private irrigation schemes produce cash crops such as tea, coffee, cashew, and sugar cane. In the National Irrigation Development Plan of 1994 (NIDP), the yields of rainfed and irrigated rice were compared and are shown in the Table 7.

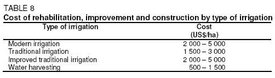

The cost for the rehabilitation, improvement, and construction of irrigation schemes was estimated by the NIMP (2002), as given in Table 8, where the lower values reflect the cost of rehabilitating irrigation canal only, while the higher costs refer to the construction or replacement of both diversion weir and irrigation canal. For the implementation of the NIMP, the operation and maintenance cost was assumed to be US$15/ha per year.

Water Management, Policies, and Legislation Related to Water Use in Agriculture

Institutions

The main institutions involved in agricultural water management are:

- The Irrigation Section (IS) within the Ministry of Agriculture and Food Security (MAFS) which is responsible for irrigation development.

- The Water Division within the Ministry of Water and Livestock Development (MWLD) which is responsible for the design, construction, equipment, maintenance, and operation of laboratories, water planning, water supply, water research, sewerage, and sanitation.

- The Central Water Board (CWB) within the MWLD which is the principal advisory body to the government on matters pertaining to the utilization of water nationally and to the allocation of water rights. It is given executive power over pollution (Water pollution) control.

- The National Environmental Management Council (NEMC) within the Ministry of Tourism, Natural Resources and Environment (MTNRE) which is the advisory body to the Government on environmental matters.

- The Regional Secretariat which is a local agency of central government with the function to encourage local governments to execute and implement policies. Its staff has been significantly reduced, and part of the personnel transferred to local governments because of the Local Government Reform Programme (LGRP), which is a major decentralization effort. In the Regional Secretariat, the agricultural officer is responsible for irrigation development.

- Local Government Authorities (LGA) which are given greater autonomy. Some executive functions are transferred to them from central government, under the abovementioned LGRP. These reforms will be critical to the delivery of support services to smallholders and rural infrastructure development. In the District Council, the District Agriculture and Livestock Development Officer (DALDO) is in charge of irrigation development. However, not all DALD Offices have irrigation officers and many are seriously understaffed.

Water Management

The responsibility for managing the water resources of the country lies with the MWLD. Water resources management involves water resources development, water allocation, pollution (Water pollution) control, and environmental protection. Until the 1990s, water was managed by the MWLD on the basis of administrative regions. Since then, the emphasis has changed to managing water resources on the basis of river basins. To strengthen river basin management, the MWLD was implementing the river basin management component of the River Basin Management and Smallholder Irrigation Improvement Project (RBMSIIP) in the Rufiji and Pangani basins. The project, the implementation of which began in December 1996, was intended to deal effectively with water management problems and improve the efficiency of smallholder irrigation.

Irrigators’ Associations (IAs), or Irrigators’ Groups (IGs), have been formed from the early 1990s onwards, for example in the Pangani basin. They are expected to become a main actor in the irrigation sector, representing part of the private sector. The rights and obligations of these groups cannot always be clearly and uniformly defined under the present legal framework. A new legal framework for the IGs seems to be very important and necessary.

Finances

The average share of irrigation development for the five years 1998/99-2002/3 was 1.46 percent of the Government’s Development Expenditure.

Policies and Legislation

The regulatory and institutional framework for water resources management is provided for under the Water Utilization (Control and Regulation) Act. No.42 of 1974 as amended by the Water Laws (Control and Regulation) Act of 1997 and the Water Laws (Miscellaneous amendments) Act of 1999. They stipulate that all water in mainland Tanzania is vested in the United Republic of Tanzania and the Minister responsible for water development is empowered to regulate the use of water from any source in any area of the country on a national basis, to declare such a source to be a national water supply for the purpose of the Act. The Law sets conditions on the use of water and appoints the Principal Water Officer, under the direction of the CWB, to be responsible for setting policy and allocation of water rights at the national level. The Water Act is currently under review. The new Act is expected to establish a mechanism for a more participatory management of water resources. With irrigation an important economic activity in most if not all of the river basins of the United Republic of Tanzania, a more balanced approach will probably be adopted.

In 1994, the National Irrigation Development Plan (NIDP) was prepared including the objectives of "Removal of Sectoral Constraints" and "Implementation of Irrigation Infrastructure". Progress so far has only been about 30 percent for the components related to both the objectives mentioned above, while completion is envisaged by 2014. The main reasons for the slow progress are inadequate institutional reforms and lack of human and financial resources.

Existing land tenure arrangements do not attract long-term commitments of resources for improving the productivity of land through irrigation or drainage. The 1999 Land Act has laid the foundation for a more transparent execution of land-based transactions and property rights. However, problems in the administrative procedures and in the use of land as collateral for obtaining credit still need to be addressed.

The Agricultural Sector Development Strategy (ASDS), finalized in 2001, focuses on the period 2002-2007 and proposes to apply the principles of integrated soil and water management, emphasizing the use of low-cost approaches by smallholders and to promote and support small-scale irrigation.

In July 2002, the Government issued the National Water Policy whose main goals are to establish a comprehensive framework for sustainable development and management of water resources and for participatory agreements on the allocation of water use. The Government will not be in charge of executive functions, i.e., the actual delivery of the services, which are the responsibility of the LGAs. Central statements of the Policy are that "water will be subject to social, economic, and environmental criteria" and that "every water use permit shall be issued for a specific duration". This could mean that irrigation might have to compete with industrial sectors and that a continuous irrigation water supply might not be guaranteed.

Environment and Health

The National Environment Policy of 1997 identified the following major environmental problems:

- Lack of accessible, good quality water for both urban and rural inhabitants

- Deterioration of aquatic systems

- Pollution (Water pollution) and poor management (Water governance) threatening the productivity of lake, river, coastal, and marine waters

The reasons identified for the above problems are inadequate water management, inadequate monitoring, and inadequate involvement of stakeholders. Alleviation of the problems will be achieved through:

- Control of the agricultural runoffs of agrochemicals to minimize the pollution of surface and groundwater

- Improvement of water-use efficiency in irrigation, including controls on waterlogging and salinization

The sectoral policy for water and sanitation of the National Environment Policy of 1997 includes:

- Planning and implementation of water resources and other development programs in an integrated manner and in ways that protect catchment areas and their vegetation cover

- Improved management and conservation of wetlands

- Promotion of technology for efficient and safe water use, particularly for water and wastewater treatment, and recycling

- Institution of user charges that reflect the full value of water resources

Existing data on the incidence of water-borne, water-related, and water-washed diseases indicate that these are mostly prevalent where people use contaminated water or have little water available for daily use. Such diseases account for over half of the diseases affecting the population.

Perspectives for Agricultural Water Management

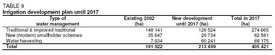

The NIMP (2002) proposed an irrigation development program that includes only smallholder schemes and is to be implemented by 2017. The whole program plans to develop a total of 405,421 ha (Table 9).

A major challenge in order to improve the irrigation sector is to overcome the following problems in irrigation schemes, as identified by the NIMP (2002):

- Lack of appropriate participatory approaches

- Unsound logical structure of projects and weak linkage between purpose and output of projects

- Misunderstanding of the concept of "simple and low-cost technology", taken to mean "easy and no concern of technical know-how and understanding"

- Lack of feedback system on the lessons learnt through actual experience in implementation of irrigation projects

- Inadequate guidelines and manuals in planning, design and construction supervision, and lack of proper application of them

- Need for an effective support system for the Water User Associations' (WUAs’) (IGs’) activities

- Lack of human resources and active participation of local government authorities in irrigation development

The public sector will gradually but increasingly limit its role to financing the provision of collective goods and services, including land and water resource utilization and management (Water governance). Mechanisms will be developed for private and public sector collaboration in the delivery of effective support services.

Floodplains, mainly used for agriculture and notably rice cultivation, have a conspicuous future in the extensive Maasai and Wembere Steppe, Usangu Plains, and the Rukwa and middle Malagarasi River basins. They are the most promising areas for the introduction of the pedal pump for lifting up water for irrigation and fish farming. Experience has shown that the use of pedal pumps allows the farmers to irrigate vegetable gardens, the benefits of which are twofold: i) as an off-farm income-generating activity; ii) vegetables could bring additional nutritional value to the village community.

The unexploited natural resource base of 40 million ha of cultivable land of the United Republic of Tanzania, abundant sources of water and several agro-ecological zones, permits virtually unlimited expansion and diversification in crop production, and in particular the development of irrigated agriculture. Such development, especially for rice and cash crop production, could contribute significantly to stabilizing agricultural production and increasing income and is, according to the above, not likely to be constrained by the supply of natural resources in the country. However, access to these natural resources may be a binding constraint in some cases.

Further Reading

- Water Resources and Freshwater Ecosystems: Tanzania. Earthtrends.

- Playing to Win: Managing Water in Tanzania. Department for International Development.

- Progess Report. Ministry of Food, Agriculture, and Cooperatives Website.

| Disclaimer: This article is taken wholly from, or contains information that was originally published by, the Food and Agriculture Organization. Topic editors and authors for the Encyclopedia of Earth may have edited its content or added new information. The use of information from the Food and Agriculture Organization should not be construed as support for or endorsement by that organization for any new information added by EoE personnel, or for any editing of the original content. |

1 Comment

Peter Fletcher wrote: 11-27-2012 01:18:59

Industrial Waste water management Training East Africa 21st & 22nd March 2013 Sea Cliffe Hotel For more information Kindly call me Fletcher on +254726840046 for early bird booking discounts