Water governance

| Topics: |

Contents

Abstract

The water sector worldwide is increasingly characterized in terms of a crisis situation. The unique and complex characteristics of the water resource entail complex social, political, and economic implications in its management. The water crisis is mainly a crisis of governance and the management forms under which water has been historically governed. In light of the problems in the water sector, public-private partnerships have been increasingly advocated and adopted throughout the world. Proponents of partnerships have often appealed to the financial gains, cost reductions, efficiency gains, environmental compliance, human resource developments, and increased services which have followed private sector engagement. Opponents of partnerships have appealed to the price increases, imbalance of power, labor disputes, inequities, environmental damage, and increased risks associated with private sector participation in water services. This paper reviews these debates to conclude that evidence can be found in support of either position. The paper argues that this dichotomous debate has lead to inconclusive and unconstructive discussions among interested parties. The paper recommended that focus be re-directed away from ideological positions on privatization towards a focus on the principals and standards which can make private participation work for the public good when it is chosen.

Introduction

Fig 1: Growth in Regional Private Investment in Water Sanitation Water resources are used in various ways by society and scientists predict that water scarcity will be one of the most important issues of the 21st century. Currently, 2.4 billion people lack access to basic sanitation and 1.2 billion people lack access to safe water sources. Nearly 2 billion people live with water scarcity, and this number is expected to rise to 4 billion by 2025, unless radical reforms emerge. Reports from development agencies, governments, water commissions, and research institutes continually point to an impending water crisis. These agencies also point to the water crisis arising from mismanagement not an absolute scarcity problem. Thus, improving current water provisions and avoiding a crisis of availability-with the entire human suffering this would entail-is possible. The message highlighted by various international efforts is that sub-optimal management of water is not an option if sustainable development is to be achieved. Throughout the history of civilization governments have grappled with the issue of water system management. Historical governance structures range from fully privatized systems to public-private arrangements to public systems. In the last decade the global water sector has experienced rising involvement of private entities in the production, distribution, or management of water and water services (see Figure 1). This ‘privatization’ has been one of the most important and controversial trends in the sector. The privatization of water encompasses a variety of water management arrangements. Full privatization is rare, and the most common form of ‘privatization’ is a partial privatization effort in the form of public-private partnerships (Water governance) . Forces driving these changes include degrading infrastructures, the inability of public water agencies to satisfy basic human water needs, and the financial strain on public entities. Controversy surrounding privatization arises from concerns regarding the ‘commodification’ of a basic human right, the multinational takeover or management of national water systems, and reports of privatization failures. Despite varying opinions, all positions agree that the global water situation requires new management of water. This paper discusses various forms of water governance with a focus on public-private partnerships and finds that evidence can build a case in favor of or against public-private partnerships. The inquiry found that a re-evaluation of the current debate is necessary with attention being re-directed away from ideological positions on privatization towards a focus on the principals and standards which can make private provision work for the public good when it is chosen.

Forms of water governance

At the crux of the water debate is governance and determining how to derive the most value from available water while not depriving people of their basic water needs. Water governance can be defined as the range of political, social, economic, and administrative systems that are in place to regulate the development and management of water resources and provision of water services at different levels of society. Counties face differing socio-economic, political, and historical contexts which will affect the way in which water resources and services are managed. However, according to Hall, most countries face a similar set of challenges and objectives with respect to water. All countries face the challenge of ensuring water infrastructure exists. Infrastructure issues include challenges such as reducing leakage, replacing and extending networks, and improving technology. As well, countries must ensure that the various social and political objectives surrounding water are addressed. These objectives include public acceptance, improving coverage, effectiveness, affordability, raising standards, ensuring transparency and accountability, and resolving international water disputes. Also, environmental and health challenges must be addressed by countries. Countries must address public health needs, environmental management, and the conservation of water. In addition, countries must make financial and managerial decisions regarding water undertakings. Financial objectives such as sustainable and equitable tariffs, effective revenue collection, financing investment and fiscal impact are decisions which must be made. Managerial objectives such as improving efficiency and productivity, evaluating administrative feasibility, capacity building, and efficient procurement must also be implemented. There are multiple responsibilities which a water and wastewater service provider faces. These include infrastructure and asset ownership, capital investment, commercial risk, and operations and maintenance.

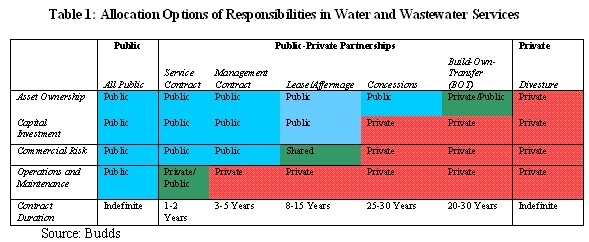

Moreover, water is a large bulky good, which often requires large capital facilities that exhibit economies of scale. The collection, storage, treatment, and distribution of water are often best served by a large reservoir due to the low average cost associate with economies of scale in the sector. This structural requirement entails that water is best organized as a ‘natural monopoly’. Thus, government regulation of the water sector is inevitable, regardless of which form of governance is chosen. There are various governance arrangements. The choice regarding which management structures can face the above challenges, objectives, decisions, and responsibilities of a country can vary from a complete public solution, to a quasi-public solution, to a fully private solution. Please see Table 1 below for a summary of governance structures in the water sector.

Public governance

Today, various forms of governance exist in the water sector. Public water provision is the most widely used governance structure under which the government takes on all of the responsibilities and challenges of water and wastewater services. The provision of water has long been considered an essential public good, and hence a core governmental responsibility. Worldwide, 85 percent of drinking water provision lies in public hands. In developed countries the public sector is the normal mode of management of water supply and sanitization services. The USA, Canada, Japan, Australia, New Zealand, and most European Union member states choose public sector management. Only the United Kingdom and France are the exceptions in which water and wastewater services are provided by the private sector or mixed management. Under a public governance structure decisions and management of infrastructure, capital investment, commercial risk, and operations and maintenance are taken on by a public entity for an indefinite period of time. Fully public management of water often takes place through national or municipal government agencies, districts, or departments dedicated to providing water services for a designated service area. Public managers make decisions, and public funds may be provided from general government revenues, loans, or charges. Governments are responsible for oversight, setting standards, and facilitating public communication and participation.

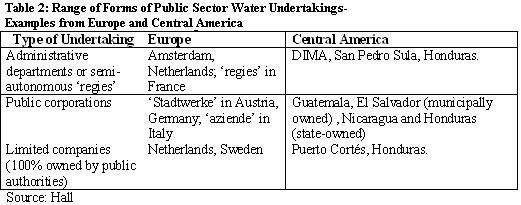

Another form of public management involves cooperatives and user associations. These management arrangements tend to be decentralized and join local uses together to provide public management and oversight. Usually customers have decision-making power through elections for different water authorities. The system is often externally audited annually. A key element of most cooperatives is that a basic water requirement should be provided to all members at affordable rates. An example in Santa Cruz, Bolivia serves nearly one hundred thousand customers. In 1997, this cooperative compared well to other Bolivian utilities in terms of efficiency, equity, and effectiveness. The group uses a varying rate structure and incorporates conservation through increasing block rates, which are not applied to the very poor. Table 2 exhibits other common forms of public sector water undertakings.

Public-private governance

In the 1990s public-private partnerships became an advocated governance approach to resolving the twin problems of decaying infrastructure and financial constraints which both threatened public capacity for meeting water needs. A public-private partnership in the water sector involves transferring some of the assets or operations of a public water system into private hands. Rapid growth in water partnerships in the 1990s was met with a decline in 2001 after a series of financial crises. Though it is too early to tell, if this downward trend will persist, specialists suggest that rising water partnerships are likely to persist. This is partially attributed to the continued support international lending institutions have for public-private partnerships. Moreover, international support for partnerships continues. For example, at the second World Water Forum in the Hague in March 2000, the ‘Framework for Action’ called for 95 percent private sector involvement for supplying investment to meet water needs. There are a variety of arrangements of public-private participation including service contracts, management contracts, leases, concessions, and build-own-transfer programs (see Table 1). Gleick et al. note eleven water system functions that can be privatized. These are:

- Capital improvement planning and budgeting (including water conservation and wastewater reclamation issues)

- Finance of capital improvements

- Design of capital improvements

- Construction of capital improvements

- Operation of facilities

- Maintenance of facilities

- Pricing decisions

- Management of billing and revenue collection

- Management of payments to employees or contractors

- Financial and risk management

- Establishment, monitoring, and enforcement of water quality and other service standards

Private-sector participation in public water companies has a long history. In this model, ownership of water systems can be split among private and public shareholders in a corporate utility. Majority ownership, however, is usually maintained within the public sector, while private ownership is often legally restricted, for example, to 20 percent or less of the total shares outstanding. Such organizations typically have a corporate structure, a managing director to guide operations, and a Board of Directors. This model is found in the Netherlands, Poland, Chile, and the Philippines.

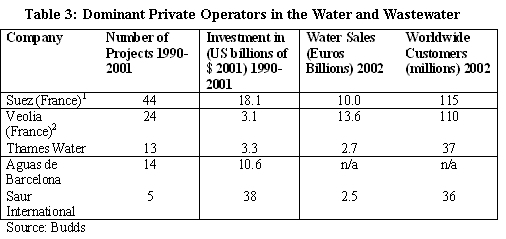

Public-private partnerships are dominated by large multinational companies lead by Suez and Veolia. Other major players in the private sector include Thames Water, Aguas de Barcelona, and Saur International. Table 3 offers a summary of projects, investments, water sales, and customers worldwide for these leading international firms.

Private companies are more attracted to partnership opportunities in water provision than sanitation. Occasionally, sanitation is undertaken by a private contractor but under conditions that it is subsidized or backed by the government with regulations for specified fees. In cases where public sewage systems are highly deficient, wastewater and sewage treatment services are contracted out by the public sector. However, it is common for water supply to be privatized separately from sanitation and for sanitation to remain the responsibility of the public sector.

The management and operation arrangements of different public-private partnerships vary. Service, management and lease/affermage contracts maintain public ownership and financing of water service management. Under these arrangements public water utilities give responsibility to the private sector for operation and maintenance activities. Such arrangements do not usually address financing issues associated with new facilities, or create better access to private capital markets. Rather, they provide managerial and operational expertise that may not be available locally. In a service contract a private firm takes responsibility for a specific task, such as installing meters, repairing pipes or collecting bills for a fee for a short period of time. Areas in which service contracts have proven effective include: maintenance and repair of equipment, water and sewerage networks, and pumping stations; meter installation and maintenance; collection of service payments; and data processing. Management contracts are arrangements under which the government transfers certain operation and maintenance activities to a private company. Management contracts are also short-term, and tend to be paid on a fixed or performance basis. Lease and affermage contracts are arrangements under which the private operator takes responsibility for all operations and maintenance functions. Here the term is longer, typically 10-15 years, and the private operator is responsible for billing and tariff revenue collection. Under an affermage, the contractor is paid an agreed-upon affermage fee for each unit of water produced and distributed, whereas under a lease, the operator pays a lease fee to the public sector and retains the remainder.

Under concession and Build-Operate-Transfer models, capital investment, commercial risk, and operations and management are undertaken by the private sector. The full-concession model transfers the entire utility and thus the operation and management responsibility for the entire water-supply system along with most of the risk and financing responsibility to the private sector. Specifications for risk allocation and investment requirements are set by the contract. Concessions are usually long-term to allow the private firm to recoup its investments. Technical and managerial expertise may be transferred to the local municipality and the community over time, as local employees gain experience. At the end of the contract assets are either transferred back to the government or another concession is granted. Build-Operate-Transfer (BOT) is a variation on the full-concession model. Here the role of government is predominately regulatory. These are partial concessions that give responsibilities to private companies, but only for a portion of the water-supply system. Another arrangement is for the private contractor to build the water supply system anew. BOT models are usually used for water purification and sewage treatment plants. The private partner manages the infrastructure and the government purchases the supply. Ownership of capital facilities may be transferred to the government at the end of the contract or remain private indefinitely. For full and partial concessions, governments and companies are finding that responsibilities and risks must be defined in great detail in the contract since such contracts are for a lengthy period. Cases of concession contracts have led to vastly different outcomes for similar physical and cultural settings.

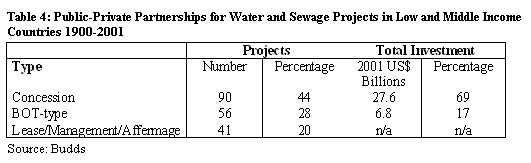

Different regions exhibit varying preferences for different contract forms. Concessions were adopted by France over 200 years ago. Recently, in Latin America and Southeast Asia, concession contracts have become a popular approach. BOT models have been popular in India for water and wastewater treatment plants. Lease and management contracts are popular in South Africa, and a few parts of sub-Saharan Africa. BOT management contracts are used for rare cases where the public sector is highly deficient in wastewater and sewage treatment such as in the cases of Jakarta, Mozambique, and Malaysia. In developing countries concession contracts are the most popular form of public-private partnerships, accounting for 44 percent of all partnerships from 1990-2001. See Table 4 for a division of contact types among developing countries.

One can simultaneously find evidence in support of or in opposition of public-private partnerships. Support for such partnerships is usually the result of improvements in financing, pricing, efficiency, risk distribution, environmental compliance, human resource management, and the services that public-private partnerships can provide. On the other hand, opposition typically arises from concerns over the economic implications of private participation, the power of corporate players, labor concerns, access inequality, envioronmental concerns, increased public risk, and inappropriate applications of private particpation. To read more, view Support and opposition of public-private partnerships.

Private governance

Private governance is the opposite of government agency provision. It is extremely rare and is often modeled under a divesture system whereby the government transfers the water business to the private sector. This model has only been adopted in a small number of cases such as England and Wales (full divestiture) and Chile (partial divestiture). In developing countries divesture accounted for only 8 percent of all worldwide private participation from 1990-2001, and accounted for a total of 16 projects during the same period. Usually, the transfer occurs through sale of the shares or water rights of the public entity. As such, infrastructure, capital investment, commercial risk, and operations and management become the responsibility of the private provider.

Fully private businesses and entrepreneurs are already found where the existing water utility has low coverage or poor service. They may obtain water directly from a water utility, indirectly from the utility through customers who have utility service, or from private water sources. In some instances, early settlers of an area privately develop water systems and later settlers become customers to the early ones. Private providers may also serve higher income groups or businesses when water is scarce or inconvenient to obtain. At the largest scale, private water companies build, own, and operate water systems around the world with annual revenues of approximately $300 billion. At the smallest scale, private water vendors and sales of water at kiosks and shops provide many individuals and families with basic water supplies. Taken all together, the growing roles and responsibilities of the private sector have grown, but not without controversy.

This study has thus far provided an apolitical view of the water sector and the forms of governance available for managing water resources. However, the debate surrounding water governance is highly contentious and ideologically charged. To read more about physical, ideological, and international forces behind public-private partnerships, please view Drivers of public-private partnerships in water governance.

Re-evaluating the debate surrounding public-private partnerships

The current heated debate surrounding public-private partnerships often seeks to prove or disprove the benefits and costs of such governance arrangements. The above arguments can all be validated in fact, and thus there is no conclusive evidence favoring one form over the other. Thus these debates have been infertile. The debaters have failed to direct their efforts to the root causes of the costs or benefits related with public-private partnerships. The debates also fail to acknowledge that public-private partnerships are limited, only 5 percent of the world’s population receives its water services from private participation. As well, the debaters can find evidence in support of their ideologically-driven claims regardless of their position. The debaters have failed to recognize that many of the problems encountered with private participation can also arise with public utilities. Likewise, the debaters fail to recognize that the benefits encountered with private participation can arise with public utilities.

These debates have been unconstructive at achieving water provision goals. This was exemplified during the World Water Forum in March 2003, where discussions among the opponents and supporters of public-private partnerships led to no conclusive decisions or agreement between both sides. Dwelling on the public-private dichotomy has diverted attention from the roles each partner should play for constructive and effective partnerships to take place. The dichotomy also focuses on the broad political trends of neoliberalism rather then objectively looking at if, how, and when private participation is or is not appropriate. Discussions which are ideologically charged tend to overlook the misguided arguments of their own position. For example, many opponents resist private participation on the grounds that water is a human right. However, there is no inherent conceptual contradiction between private sector participation and the achievement of human rights. As well, the debates fail to recognize that neither public nor private utilities are well suited to serve the majority of low income or rural households who currently have inadequate water and sanitation and make up the appalling 1.1 billion and 2.4 billion figures offered in examples of the failure to provide water needs. Moreover, seeking universal dichotomous solutions to a complex and diverse issue such as water is a discussion which leads to no solution. Under the right circumstances, it may well be possible for private sector participation to improve efficiency and increase the financial resources available for improving water and sanitation services.

However, much depends on the way private participation is developed and the local context. There is a great danger in the international promotion of public-private partnerships through conditional development assistance and finance. Partnerships do not apply to all circumstances, to all developing countries, nor to all regulatory and political frameworks. Failure to recognize these facts on behalf of international financial institutions has lead to an application of partnerships in contexts to which they do not apply and has further fuelled the debate surrounding private participation. What is required in discussions surrounding water governance is a focus on the principals and standards which can make private provision work for the public good when it is chosen.

Recommendations for public-private partnerships

At the bottom of this governance debate lie two fundamental goals that all parties would agree must be reached: improving the water supply and protecting the public interest. Any form of water governance which does not achieve these two goals will not sufficiently resolve the water woes of today or the future. There are numerous cases of failures and successes from which lessons in governance can be learned, and principals and standards for effective governance can be derived. Since public-private partnerships are unlikely to disappear and are more likely to increase due to the driving forces mentioned in this paper, attention to the principals and standards for effective public-private partnerships should be granted in discussions between interested parties. Historically, this attention has been diverted to dichotomous debates over private participation, and change is called for. Gleick et al. have devised a set of excellent principals and standards for public-private partnerships based on the lessons learned from successful and unsuccessful cases. These principles and standards are repeated here as a starting point for more constructive discussions among interested parties.

Principal 1: Continue to Manage Water as a Social Good

Ultimately, water is vital to life, and certain water systems are of national strategic importance. Contract agreements to provide water services in any region must ensure that unmet basic human water needs are met first, before more water is provided to existing customers. Basic water requirements should be clearly defined by the contract. All residents in a service area must be guaranteed a basic water quantity under any form of governance. Moreover, basic water supply protections for natural ecosystems must be put in place for every region. These protections should be written into the contract agreement and should be enforced by the government. Finally, the basic water requirement for users should be provided when necessary for reasons of poverty. These subsidies should not be implemented universally, but when specific groups of people or industries require these subsidies to maintain basic survival.

Principal 2: Use Sound Economics in Water Management

The provision of water and water services should not be free. Water and water services should be provided at fair and reasonable rates, which should be discussed with the public transparently. Rates should be designed to encourage efficient and effective use of water. Whenever possible, proposed rate increases should be linked with agreed-upon improvements in service. Experience has shown that water users are often willing to pay for improvements in service when such improvements are designed with their participation and when improvements are actually delivered. As well, subsidies, if necessary, should be economically and socially sound. Finally, private participation agreements should not permit new supply projects unless such projects can be proven to be less costly than improving the efficiency of existing water distribution and use. When considered seriously, water-efficiency investments can earn an equal or higher rate of return. Rate structures should permit companies to earn a return on efficiency and conservation investments.

Principal 3: Maintain Strong Government Regulation and Oversight

The “social good” dimensions of water cannot be fully protected if ownership of water sources is entirely private. Permanent and unequivocal public ownership of water sources gives the public the strongest single point of leverage in ensuring that an acceptable balance between social and economic concerns is achieved. Thus, governments should retain or establish public ownership or control of water sources. Moreover, governments and water-service providers should monitor water quality. Governments should define and enforce laws and regulations. Clearly defined roles, responsibilities, and risk-sharing frameworks among partners, written in the contract, should be the prerequisite of any form of private governance. Government agencies or independent agencies should monitor, and publish information on water quality. Where governments are weak, formal and explicit mechanisms to protect water quality must be even stronger. All contracts must explicitly lay out the responsibilities of each partner. The contracts must protect the public interest which requires provisions of ensuring the quality of service and a regulatory regime that is transparent, accessible, and accountable to the public. Good contracts will include explicit performance criteria and standards, with oversight by government regulatory agencies and non-governmental organizations. Moreover, contracts and regulatory institutions must have clear dispute resolution procedures in place prior to engaging a private partner. It is necessary to develop practical procedures that build upon local institutions and practices which are free of corruption. During the bidding process all competing firms should be treated equally. Contract reviews by an independent body should be a requirement of all partnerships, thus avoiding acceptance of weak and unfavorable contracts. Thus, ambiguous contract language or inappropriate reviews of contracts can be avoided, and only sound contracts will be put in place. Finally, negotiations over private participation should be open, transparent, and include all affected stakeholders. Numerous political and financial problems for water customers and private companies have resulted from arrangements that were perceived as corrupt or not in the best interests of the public. Stakeholder participation is widely recognized as the best way of avoiding these problems. Broad participation by affected parties ensures that diverse values and varying viewpoints are articulated and incorporated into the process. It also provides a sense of ownership and stewardship over the process and resulting decisions.

In addition, Hall suggests that governments should always consider the public sector option before engaging a private partner. He recommends that the public option should be contracted and capability for reforms should be evaluated. The private proposal can then be evaluated against the public sector option, in a public and transparent process. During this process secret agreements and secrete contracts must be avoided and stopped. Considering and discussing these standards and principles is a starting point for constructive discussions among opposing parties in the public-private partnership debate.

Conclusion

The solution to the current and future water crisis will be found in changes to the way water is used and managed. Effective changes in water governance are the key to sustainable water management in the future. Physical, ideological, and international forces have encouraged public-private partnerships. Despite the promises of this form of governance, there have been gains and losses associated with its adoption. The current problems in governance structures cannot be ignored and a re-evaluation of the debate surrounding public-private partnerships is necessary. Future research and discussions should focus less on a dichotomous debate on partnerships and rather on a constructive debate on how, when, where and why public-private partnerships work. There is little research in the area of developing principles and standards for effective public-private partnerships. Public-private partnerships offer promise to the water sector as well as perils. The author recommends that future research efforts be channelled at developing effective standards for public-private partnerships in the water sector.

Further Reading

- Adelson, N. 2002. “Water Woes: Private Investment Plugs Leak in Water Sector”. Business Mexico.

- Alexander, N. 2002. “Who Governs Water Resources in Developing Countries? A Critique of the World Bank’s Approach to Water Resource Management”. News and Notices for IMF and World Bank Watchers. Vol.2.

- Barlow, M. 1999. Blue Gold: The Global Water Crisis and the Commodification of the World’s Water Supply. International Forum on Globalization. Sausalito, California.

- Blokland, M., O. Braadbaart, and K. Schwartz (editors). 1999. Private Business, Public Owners: Government Shareholdings in Water Enterprises. Ministry of Housing, Spatial Planning and the Environment, The Hague, the Netherlands.

- Borkey, P. 2003. “Water Partnerships: Striking a Balance”. Observer No. 236, pp. 13- 15

- Budds, J. and McGranaha G. 2003. “Are the Debates on Water Privatization Missing the Point? Experiences from Africa, Asia and Latin America”. Environment and Urbanization. Vol 15, pp, 87-113

- Duda, A. 2003. “Integrated Management of Land and Water Resources Based on a Collective Approach to Fragmented International Conventions”. The Royal Society. pp. 2051-2062

- Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). 1995. Water sector policy review and strategy formulation: A general framework. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Rome, Italy.

- Franceys, R. and Weitz, A. 2003. “Private Sector Participation in Water Supply and Sanitation”. Waterlines. Vol. 21, 2-4

- Gleick, P.H. 1999. “The human right to water.” Water Policy, Vol. 1, pp. 487-503.

- Gleick, P.H. 2001. “Global water: Threats and challenges facing the United States. Issues for the new U.S. administration.” Environment. Vol. 43, No. 2, pp. 18-26.

- Gleik, P.H., Wolff, G., Chalecki, E.L., Reyes, R. 2002. The New Economy of Water: The Risks and Benefits of Globalization and the Privatization of Fresh Water. Pacific Institute. Oakland, California.

- Global Water Partnership (GWP). 2000. Toward Water Security: A Framework for Action to Achieve the Vision for Water in the 21st Century. Global Water Partnership, Stockholm, Sweden.

- Global Water Partnership (GWP). 2002. Dialogue on Effective Water Governance. Global Water Partnership, Stockholm, Sweden.

- Graz, L. 1998. “Water source of life.” FORUM: War and Water. International Committee of the Red Cross, Geneva, Switzerland, pp. 6-9.

- Gopinath, D. 200. Blue Gold. Institutional Investor International Edition. February.

- Hall, D. 2001. Water in Public Hands. Public Services International Research Unit. London, UK.

- Hansen, F. 2004. “Renewed Growth in Public-Private Partnerships”. Business Credit. Vol. 106, pp. 50-55

- Id21 Insights. 2001. “Issue 37: Tapping the Water Market: Can Private Enterprise Supply Water to the Poor”. Sussex, UK.

- International Conference on Water and the Environment (ICWE). 1992. The Dublin Principles.

- ITT Industries. 2003. Guidebook to Global Water Issues. ITT Industries.

- Komives, K. 2001. “Designing pro-poor water and sewer concessions: Early lessons from Bolivia.” Water Policy. Vol. 3, No. 1, pp. 61-80.

- Orwin, A. 1999. The Privatization of Water and Wastewater Utilities: An International Survey. (Environment Probe, Canada)

- LeClerc, G. and Raes, T. 2001. Water a World Financial Issue. PriceWatehouseCoopers. Sustainable Development Series. Paris, France.

- Perry, C.J., M. Rock, and D. Seckler. 1997. Water as an Economic Good: A Solution, or a Problem? International Irrigation Management Institute, Research Report 14

- Rivera, D. 1996. Private Sector Participation in the Water Supply and Wastewater Sector: Lessons from Six Developing Countries. The World Bank, Washington, D.C.

- Rodrigues, R. 2004. “The Debate on Privatization of Water Utilities: A Commentary”. Water Resources Development, Vo. 21 pp. 107-112

- Savas, E.F. 1987. Privatization: The Key to Better Government. Chatham House, Chatham, New Jersey.

- Senia, A. 2002. “Global Thirst”. Utility Business. Vol.5, pp. 14-19.

- Tate, D. 2000. The Water Page: Public-Private Partnership Page. Surrey, UK.

- Totajada, C. and Biswas, A (editors). 2003. Water Pricing and Public-Private Partnerships in the Americas. Inter-American Development Bank. Washington, D.C.

- United Nations (UN). 1997. Comprehensive Assessment of the Freshwater Resources of the World. United Nations, New York.

- United Water (2003)

- World Bank. 2003. Public-Private Partnerships in Management of the Water Services: An Effective Approach. Washington, D.C.

- World Commission on Water for the 21st Century. 2000. A Water Secure World: Vision for Water, Life, and the Environment. World Water Vision Commission Report. The Hague, Netherlands.

- Water Partnership Council (WPC). 2003. Establishing Public-Private Partnerships for Water and Wastewater Systems: A Blue Print for Success. Water Partnership Council. Washington, D.C.

- Webb, P. and Iskandarani, M. 2001. “The Poor Pay Much More for Water and Use Much Less, Often Contaminated”. Newas Newsletter: Water and Sanitation Update.

- Yepes, G. 1992. Alternatives for Managing Portable Water and Sanitation. National Department of Planeación. Bogotá, Colombia. p.111-116.