Support and opposition of public-private partnerships

Contents

Evidence in support of public-private partnerships

There are numerous reasons why the international and policy community has supported private participation in water services. Public-private partnerships have gained support due to the improvements in financing, pricing, efficiency, risk distribution, environmental compliance, human resource management, and service they can provide. Moreover, successful partnerships such as those in Milwaukee, Paris, Buenos Aries, and Mexico City have fostered support for public-private partnerships as a solution to the prevalent problems in water governance.

Financing and costs

One of the most frequently cited reasons for public-private partnerships is the need for capital. The private sector can supply capital in return for a profit opportunity. Lack of public funds is attributed to reasons such as international debts, national deficits, and lack of political will to fund ‘in ground assets’ non-visible assets. In many nations throughout the world capital availability for public water projects has declined amid a growing need to upgrade infrastructure to meet new demands. The second World Water Forum in the Hague in March 2000 called for $180 billion per year in new investment to meet drinking water, sanitation, waste treatment, and agricultural water needs between now and 2025—95 percent of which should come from the private sector. As capital providers private water companies have already been successful and effective, specifically in France where the private sector rebuilt water infrastructure following the destruction of World War II.

In addition, private sector solutions are known to optimize capital expenditures by introducing new technologies, reducing water leakage, collecting water bills, and recouping costs of services. According to the Water Partnership Council, public-private partnerships significantly reduce operating costs, with partnerships resulting in annual operating cost savings of 10 to 40 percent in municipalities. Moreover, governments which engage private partners tend to experience cost savings by transferring associated operating and maintenance costs to the private sector. Additional savings to end-users is another financial incentive proponents adhere to. For example, a water service contract in Buenos Aries calls for a 27 percent reduction in user fees over its lifetime. Moreover, the problem of poor users paying more than wealthy users in developing countries is a problem the private sector claims it can solve. For example, in Lima, Peru a poor unconnected family on average pays over twenty times what a middle class family pays, even through the poor family uses, on average, one-sixth as much water as the middle class family with a network connection. Under public-private partnerships, proponents argue that the urban poor can gain network connections which would reduce their cost for water. However, it remains debatable if the private sector would provide network connections and lower costs to the rural poor.

Implementation of markets and full-cost pricing

Many wasteful practices such as over usage and overbuilding of water-related infrastructure have been attributed to a lack of markets for water services. It is thought that introduction of the private sector into water services can introduce market efficiency. For example, competitive bidding among private partners for contracts can introduce a quasi-market into the water industry which would establish a drive for efficiency. Moreover, private participation can change the water pricing system, so that full-cost pricing can be implemented and overuse of water resources curtailed. Currently governments are constrained to implement full-cost pricing due to the political process and historical precedence of water as a free public good. Thus, private providers, who are not susceptible to the political processes in can better achieve pricing reforms while the government can avoid raising water rates directly.

Efficiency and expertise

Private firms are also noted for their efficiency and expertise, brought about by the competitive market forces to which they are subjected. Empirical evidence suggests that public-private partnerships have achieved a high level of efficiency and quality of service. In the 1990s private-public partnerships in Cartagena, Colombia and Córdoba, Argentina achieved remarkable gains in efficiency of water supply delivery (see Table 1). Thus, proponents suggest that introduction of a private partner can bring about efficiency and expertise that would otherwise not be available to the public sector.

Decreased liability risk

Significant operational, financial, and environmental risks go along with managing water and wastewater systems. Generally, if a party has an equity interest in a particular type of capital facility there is an inherent incentive to manage that facility effectively and even optimally. When a water system is owned by the public there is no equity interest on the part of personnel who operate the systems. Proponents of private participation claim that private firms with an equity interest in water system facilities would have the incentive to operate facilities more effectively than public-sector employees. As well, under a public-private partnership liability risks are spread among the partners. Thus, it is argued that liability risks are reduced under private partnership arrangements.

Environmental stewardship

Environmental stewardship has improved under public-private partnerships in many developed countries. For example, in the United States prior to partnerships, 29 percent of drinking facilities were not in full compliance with environmental regulations, yet one year into partnerships all facilities were meeting or surpassing regulator standards. Proponents claim that such performance is due to a private firm’s interest in maintaining a good reputation through clean water and compliance with regulatory standards. A good reputation ensures a firm’s ability to obtain new contracts in the future and to maintain long-term growth. Proponents also claim that financial capability of private partners entails that the technology and the management tools for regulatory compliance will be implemented. Although evidence in developed countries suggests environmental stewardship improves under partnerships, the applicability of this argument to developing countries is less clear due to the lack of evidence.

Human resource improvements

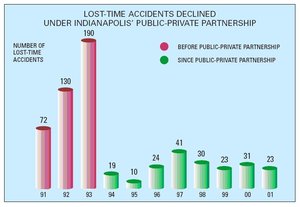

Another benefit of public-private partnerships is the improvement in work environments and opportunities for employees they can provide. Safety improvements have occurred with private partnerships. For example, in Indianapolis accidents declined significantly with the introduction of a public-private partnership (see Figure 1). In the United States it is documented that private partners have employed rigorous safety protocols with each employee undergoing intensive safety training. Also, employee grievances have declined under private partner participation. For example, in Indianapolis employee grievances significantly declined with the introduction of the private partnership (see Figure 2). Proponents attribute these changes to the desire of a private firm to minimize liability risk as well as its implementation of favorable management practices in the view of improving performance. These improvements have been documented for developed countries, though information of similar quality is unavailable for public-private partnerships in developing countries.

Increased service provision

Finally, increased service provision is one of the main factors proponents for private-partnerships point to in favor of this form of governance. Where contracts have been appropriately structured, private operators have increased connections to consumers, particularly poor consumers. For the developing world, private participation is seen as crucial for improving access and affordability to poor urban consumers. For example, in Manila 400,000 lower-income consumers have benefited from private partners providing affordable connection charges. Likewise, in Buenos Aires, private participation lead to an increase in the population served from 70 percent prior to the partnership to 85 percent after partnership, an increase of 1.6 million people, including 800,0000 living in poor neighborhoods. Thus, supporters of private participation point to the gains in service brought about with engagement of the private sector.

Cases in support of public-private partnerships

There are several cases in developed and developing countries worthy of notice in a favorable discussion of private participation in the water sector. Successful partnerships in the United States and France exhibit the benefits private partners can provide for developed regions. Successful partnerships in Argentina and Mexico exhibit the benefits private participation has brought to developing regions.

United States: Successful Private Participation in Milwaukee

In 1998, United Water (A subsidiary of Lyonnaise des Eaux) signed a 10 year contract with Milwaukee Metropolitan Sewage District to reduce costs and improve the city’s sewage collection systems and wastewater treatment plants. The public-private participation effort drastically improved performance, placing Milwaukee among America’s top ten performing facilities. The improved operating standards and declined effluent discharges, resulted in numerous awards including the AMSA Platinum and Gold Awards. Moreover, operation costs were reduced 30 percent since the inception of the contract. Employee performance improved significantly with a 50 percent reduction in workplace injuries, sick days, and grievances. Thus, appointment of a private partner was successful for Milwaukee.

France: Successful Private Participation in Paris

In 1985, Lyonnaise des Eaux signed a lease contract with the City of Paris to distribute drinking water along the Seines’ Left Bank. The benefits derived from the contract included gains in economic and technical efficiency as well as improvements to the water supply network. Water loss reduced under the partnerships with saving in water of almost 10M cm per year. Also, 45 percent of the network in need of repair prior to contract was rehabilitated under the partnerships. The public-private partnership was considered a success.

Argentina: Successful Private Participation in Buenos Aires

In 1993, a contract for private participation by Aguas Argeninas (a subsidiary of Suez) was signed for Buenos Aires, Argentina. The private participation led to rapid improvements in water availability. The percentage of the population served increased from 70 percent to 85 percent, an addition of 1.6 million customers. A 38 percent increase in drinking water capacity was developed, thus ending the problem of summer water shortages. The privatization reduced staff by 50 percent, reduced non-payment of water bills from 20 percent to 2 percent, and resulted in a more modern and efficient billing and water-delivery operation. Customer satisfaction improved upwards to 70 percent. Also, the contract governing the privatization action requires a 27 percent decrease in water prices over time. This case is one of the most noted for exemplary private participation.

Mexico: Successful Private Participation in Mexico City

Historically, Mexico City had problems of over-exploitation of the water table and unacceptable water losses in distribution. The government decided to entrust service to four private operators to reduce physical losses and improve invoicing. Thus far, the private-public sector partnership has been fruitful for both sides. In 1997, the city was losing 37 percent of its water to leakage. By 1998, leakage reduced to 34.2 percent, and in 1999, leakage fell to 32 percent. The private sector also brought leaps in technology for the city, by replacing sewer mains without excavations. A technology developed in the United Kingdom that avoids destroying sidewalks and streets to reach the pipes. Also, the private partner replaced asbestos cement pipes with polyethylene ones, for health improvements. By engaging a private partner Mexico City met the loan requirements of the International Development Bank and obtained a much needed US$365-million loan. For Mexico City a public-private partnership has proved beneficial.

Evidence in opposition to public-private partnerships

Despite these apparent benefits of private sector involvement there is also evidence which fosters opposition to this form of governance. Opposition arises from concerns over the economic implications of private participation, the power of corporate players, labor concerns, access inequality, environmental concerns, increased public risk, and inappropriate application of private participation. The discussion will now turn to each of these concerns.

Private participation in natural monopolies

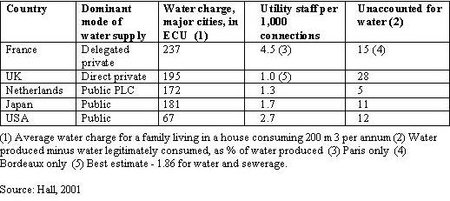

Economically, concern arises regarding private participation in natural monopolies. As early as the 19th century, the prominent economist, J.S. Mill argued that natural monopoly conditions would lead to private sector companies engaging in wasteful competition since only one survivor would confer from the price warfare among competitors. Once this natural monopolist eliminated competitors it would raise price and lower output to maximize profit. Since the time of J.S. Mill governments were advised to own and operate, or strictly regulate, natural monopolies. The provision of water services is a natural monopoly due to its economies of scale. Yet, public provision of the service can lead to inefficiencies as well. Thus, to all inefficiencies a partnership situation is recommended by economists. Hence, the concession private-partnership approach adopted in France. Despite the theoretical ability for partnerships to eradicate the ills of natural monopolies such as price increases, experience shows that price increases are common with the engagement of private partners. In France, figures show a consistent picture of the private concessions charging higher prices then public water utilities. Table 2 exhibits these tendencies.

The reason for price increases under a private partnership arrangement is often explained by the new set of financial demands, i.e., the requirement for profit and dividends, introduced with the private partner. Thus, opponents disagree that natural monopolies can successfully appoint private partners to overcome the inefficiencies associated with natural monopolies.

Balance of power

A great concern among opponents to private participation is the balance of power between governments and multinational corporations. During contract negations weak governments have signed contracts with unfavorable conditions for the public. For instance, some governments have allowed a loss of local ownership of water systems which in turn neglected public water rights. Many of the concerns expressed about privatization relate to the control of water rights and changes in water allocations, rather than explicit financial or economic problems. Often changes in access and water rights occur without explicit agreement and lead to escalating conflict. For example, the proposal to privatize water systems in Cochabamba, Bolivia sought to restrict unmonitored groundwater pumping by rural water users, thus imposing a fundamental change in the historical use rights in the region and creating a cause for violent conflict. The failure of weak or incompetent governments during negotiations has led to contracts in which basic water needs are not provided by the private or public partner. Opponents claim that failure to satisfy basic water services by governments cannot be resolved by simply shifting efforts to private partners. Rather, government supervision, competency, and responsibility are fundamental when engaging a private partner. However, many developing country governments have shifted responsibility without considering the necessary governmental role.

Governments with high indebtness seeking a private partner for financial support are often in a weak negotiation position. In the pursuit of partners to ease financial constraints, governments have often failed to define broad guidelines for public access, oversight, and monitoring. These failures have lead to ineffective service provision, discriminatory behavior, or violations of water-quality protections. The case of Guinea exhibits theses tendencies where in private participation united with weak monitoring and enforcement led to few gains. Likewise, many private participation agreements have lacked transparency or stakeholder involvement, thus furthering sentiments against private participation.

Finally, the loss of power that some public-private partnerships allow leads to opposition to this form of governance. Firstly, the long duration and administrative effort involved in most contracts entail a legal constraint and difficulty in canceling contracts. For example multinationals have pursued legal claims against governments in the cases of Tucumán, Argentina, and Cochabamba, Bolivia when governments wanted termination of contract. Secondly, the long-term transfer of functions to the private partner can create a dependency for private involvement indefinitely as public management expertise, engineering knowledge, and other assets are lost. Opponents note that there is little experience with the public sector re-acquiring such assets from the private sector.

Labor concerns

Labor organizations and their members often object to increased private sector involvement in water services. They claim that job losses, job insecurity, and poor pay may follow private sector involvement. Despite the cases noted in the above section, there is evidence that private operators may reduce staff by 20 or 30 percent in order to achieve productivity improvements or cost reductions. For example, in Buenos Aires staff was reduced 50 percent with the take over of operations by a private partner. Despite these concerns, cases show that labor issues can be resolved if an explicit understanding of staff cuts and the consequences for employees is transparently discussed at the outset of the partnership.

Inequality

Much attention has been paid to serving low-income groups under private sector involvement in water services. Policy literature suggests that the private sector, through external funding, greater efficiency and customer service, will extend and improve services to low-income groups. According to this argument, un-served groups represent a large and untapped market for the private sector. However, there is little evidence to support favorable claims.

First, private participation in the water sector has a regional bias. Regionally, the there is a lack of private interest in the water and sanitation sector in the South compared developed countries. Among countries of the South, the private sector is biased towards serving more developed and richer countries. For example, Sub-Saharan Africa, excluding South Africa, is the most underserved region of the world in terms of private sector participation. The lack of private participation in poor regions such as Africa was eloquently expressed by a manager of Biwater who said: "Investors need to be convinced that they will get reasonable returns. The issues we consider include who the end users are and whether they are able to afford the water tariffs. From a social point of view, these kinds of projects are viable but unfortunately from a private sector point of view they are not". Moreover, when private participation exists in the South, the water sector has been the least attractive to private investors, and the sums invested have been the smallest. Only 5.4 percent of all private commitments to infrastructure during the 1990s in the South were in water and wastewater services. Thus, private participation is unlikely to resolve regional inequalities among nations in terms of water service provision for populations.

Similarly, within countries private companies have a regional bias in favor of urban populations. Often, services to the rural population are not extended under public-private partnerships. Although there are documented cases (see above) of private participation increasing access to water services these tend to occur where projects are large scale, have a contract value of at least US$ 100 million, and serve at least 1 million urban inhabitants. Yet, more than 80 percent of the ‘un-served’ population of the world lives in rural areas. The private sector is reluctant to take on projects servicing rural populations due to the lack of return. As the Chief Executive of Saur noted, “Is a false belief that any business must be good business and that the private sector has unlimited funds […] The scale of the need far outreaches the financial and risk taking capacities of the private sector”. Also, under-served communities often lack the political power to encourage water service provision to their regions. Thus, private participation is unlikely to improve the majority of already underserved communities.

Secondly, private participation has a class bias in favor of richer populations regardless of region. Low-income populations do not represent attractive markets due to their inability to pay and the financial risk involved in serving these groups. Representatives of Veolia have stated that profits depend on “sufficient and assured revenues from the users of the service”, which are unlikely to include poor groups. Moreover, there is evidence that attempts by the private operator to serve low-income groups have seldom been successful from a commercial perspective. For example, in La Paz, Bolivia, a concession was awarded to a Suez-Lyonnaise subsidiary in 1997. The contract included explicit targets for extending connections to poor households. The contract has not however provided adequate financial incentives for the company to make extensions in some areas, due to operating losses, and it is suggested that the services offered to the poor should be determined by ability to pay rather than by public policy. Moreover, in the often heralded case of Buenos Aires, where 800,000 urban poor gained accesses to water services, access was achieved with difficulty. A cross-subsidy on wealthier users was imposed which caused a crisis for the multinational, required a complete rewriting of the concession contract, and was resisted by consumers who took the multinational to court. Aware of these problems, private companies often exclude poor areas from contract coverage. Operators may also exclude poor households that are within the contract area on the grounds that they do not have legal land tenure. This was the case in Córdoba, despite the contracts stipulating almost universal coverage in the service areas. Thus, private participation can often worsen the neglect of under-represented and underserved communities.

Objections in terms of inequality are furthered since the profits of private participation accrue to multinational corporations based in the wealthiest countries, while the prices are paid by people living in poor countries. Thus, there is great concern among opponents that private sector involvement may fail to mitigate, or could worsen inequalities among urban populations, rural communities, countries, and classes.

Environmental concerns

Opponents point to several negative environmental consequences that have arisen from inappropriate and poorly constructed private contracts. Contracts that do not guarantee ecosystem water requirements can undermine ecosystem health in the pursuit of new water supplies over a long period of time. Opponents fear that weak or inexperienced governments will not make the appropriate provisions for ecosystem protection when drafting contracts with private participants. Another concern among opponents is that private firms have little incentive to encourage conservation due to the profit motive. Conservation, which is less capital-intensive, offers fewer ank paper: “…the privatization process itself can create corrupt incentives. A firm may pay to be included in the list of qualified bidders or to restrict their number. It may pay to obtain a low assessment of the public property to be leased or sold off, or to be favored in the selection process …firms that make payoffs may expect not only to win the contract or the privatization auction, but also to obtain inefficient subsidies, monopoly benefits, and regulatory laxness in the future”.

In Europe, bribery by French water multinationals has occurred. In one case, in Grenoble a former mayor, government minister, and a senior executive of Lyonnaise des Eaux received prison sentences for receiving and giving bribes to award of a contract to a subsidiary of Lyonnaise des Eaux. In another case, in Angoulème, the former mayor was jailed in 1997 for two years, with another two years suspended, for taking bribes from companies bidding for contracts, including Générale des Eaux. In Lesotho, subsidiaries of a dozen multinationals - from the UK, France, Italy, Germany, Canada, Sweden and Switzerland - are being prosecuted for paying bribes to obtain contracts in the Lesotho Highlands project – a huge water supply scheme. The companies included subsidiaries of Suez-Lyonnaise, Bouygues, and Thames Water.

Weak accountability on the part of private firms is also a concern for opponents to public-private partnerships. In many countries regulations are not in place, or lack transparency, or are vulnerable to political interference. Lack of public sector capacity is problematic due to the strong government regulation partnerships require in order to prove successful. A study of public-private-partnerships in South Africa concluded that lack of public sector capacity is an important reason not to privatize, rather than a justification for public-private sector partnerships. The same is true in the countries of the former Soviet Union where the weak capacity of most NIS governments to effectively regulate private sector participation constrains the development of partnerships. Despite this knowledge private participation has been pursued in the presence of weak government regulations as in the disastrous case of South African private participation.

A related risk is the lack of transparency and the secrecy of contracts which occurs in many public-private contracts. Lack of transparency is a widespread problem which holds risks that the public interest may be ignored. For example, in Fort Beaufort, South Africa, the contract prevents any member of the public from seeing the contract without the explicit approval of the company, Suez-Lyonnaise. Similarly, documents relating to the privatized Vivendi Budapest Sewerage Company are kept secret, even from council officials. In Morocco, a Suez-led consortium was awarded a multiple concession for water and energy in Casablanca by King Hassan, of which the city council was not even informed until later. The private sector in practice rarely includes a role for the community for which its contracts are intended to serve.

Finally, failure of contract is a risk involved in relying on private firms. Private sector firms can encounter technical or economic difficulty and may be unable to deliver the promised services. The bidding process often results in firms bidding low at a loss in order to outbid competitors and secure the market. These practices run the risk of failure to recover costs and to achieve financial sustainability, which can lead firms to pull out of contracts or become unable to provide services. This would leave the public agency in a difficult position. For example, in 1999 Azurix a subsidiary of Enron outbid its competitors and won the contract to serve two of the three regions of Buenos Aires, Argentina. It subsequently invested $94 million. Failing to recover the costs of the bid, in January 2001 Azurix took a one-time charge of $470 million in an acknowledgement that the terms of the contract prevented them from adequately raising capital or receiving an appropriate return on investment. These risks are worsened by the fact that many public-private contracts often lack dispute-resolution procedures. Public water companies are usually subject to political dispute-resolution processes involving local stakeholders. Privatized water systems are subject to legal processes that involve non-local stakeholders and perhaps non-local levels of the legal system. This change in who resolves disputes, and the rules for dispute resolution, is accompanied by increased potential for political conflicts over privatization agreements. In the case of water resources, these risks are critical because the service provided has an "essential" characteristic.

Inappropriate private participation

Furthermore, private participation has been universally supported by international institutions and current literature regarding the water sector, regardless of its applicability. There is an inherent assumption that public-sector providers are inefficient and must be replaced or guided by private participants. These beliefs cannot be applied universally to all cases, yet trends in the water sector suggest that private participation is occurring even where efficient public sector operations exist. For example, most Chilean water undertakings have been partly privatized, yet these same companies were previously held up as examples of efficiency, even by the World Bank. Moreover, public provision of water services does not necessarily imply that water services are inferior. Table 3 demonstrates the equal capability or public or private providers in the water supply sector.

Across all regions there are examples of well performing public-sector water services. Examples are drawn from cities in a diverse range of countries, including Sao Paulo, Brazil; Debrecen, Hungary; Lilongwe, Malawi; and Tegucigalpa, Honduras. Moreover, there are numerous examples of public water suppliers undertaking successful reforms for improving efficiency, achieving modernization, implementing price reforms, expanding services, and reducing costs without the private sector involved.

One often overlooked benefit of public provision of water resources is the government’s ability to sway public behavior for effective conservation of water resources. For example, during a drought in the UK in 1976, when water was under public ownership, there was an appeal for the public to cut consumption of water. The response was a reduction of about 25 percent in usage. In 1995, when the privatized Yorkshire water faced a drought and made a similar appeal, the public did not make a reduction in their usage.

Cases in opposition to public-private partnerships

There are several cases worthy of notice in a discussion against private participation in the water sector. Unsuccessful partnerships in Puerto Rico, Trinidad, Argentina, and Bolivia exhibit the perils of private participation in water services.

Puerto Rico: Unsuccessful Private Participation

In 1995 Puerto Rico contracted the management of their water authority, PRASA, to Vivendi, through a subsidiary called Compania de Aguas. In August 1999, an official report condemned the contract for failing on all grounds. The Puerto Rico Office of the Comptroller (Contralor) issued an extremely critical report on the PRASA-Compania de Aguas contract. The document lists numerous faults, including deficiencies in the maintenance, repair, administration and operation of aqueducts and sewers, and required financial reports that were either late or not submitted at all. Citizens asking for help received no replies, and some customers complained that they did not receive water, but always received their bills on time, charging them for water they never received. As operating deficit got worse, PRASA had to appeal for emergency funding and to provide subsidies of $241.1 million to the private operator. Thus, management and financial failure on the part of the private partner lead to controversy and dissatisfaction with the contract.

Trinidad: Unsuccessful Private Participation

In 1994, the government of Trinidad contracted out the management of the islands’ water authority, WASA, to Severn Trent. One of the central features of the original Business Plan submitted by Severn Trent was that they would make WASA financially viable by the end of the three-year contract period. However, by 1998 the deficit increased to $378.5 million. In April 1999 Severn Trent’s contract expired without renewal and the public sector took back responsibility and operation of the water utility. The failure of contract resulted in a unsuccessful contract for the public.

Argentina: Unsuccessful Private Participation in Tucumán, Argentina

In 1995, Aguas del Aconquija, a subsidiary of Vivendi won a 30-year concession to run the water supply system for 1.1 million people in Tucumán. The private partner doubled water tariffs within a few months time in order to meet the aggressive investment requirements specified in the concession. Due to political opposition and change in water quality, 80 percent of residents stopped paying their bills. In October 1998 the government terminated the concession. Vivendi agreed, but quickly filed a US$100 million suit against the government, and joined several other companies who had filed complaints against Argentina with the World Bank arbitration panel.

Bolivia: Unsuccessful Private Participation in Cochabamba, Bolivia

In 1999, the Bolivian government privatized the water system of Cochabamba, partly in response to pressures from the World Bank to make structural adjustments to its economy. The government granted a 40-year concession to run the water system to a consortium led by Italian-owned International Water Limited and U.S.-based Bechtel Enterprise Holdings. Rate structures were immediately modified, putting in place a tiered rate and rolling in previously accumulated debt. As a result, many local residents received increases in their water bills. Aguas de Tunari maintained that the rate hikes would have a large impact only on industrial customers; however, the poor peasants claimed that increases as high as 100 percent were experienced. In October 1998, groups gathered in protests from which an outbreak of violence followed. During the protests, the Bolivian army killed as many as nine, injured hundreds, and arrested several local leaders. Subsequently, the government cancelled its contract with Aguas de Tunari. Clearly, this was disastrous outcome of private sector involvement.

Further Reading

- Budds, J. and McGranaha G. 2003. Are the Debates on Water Privatization Missing the Point? Experiences from Africa, Asia and Latin America. Environment and Urbanization, 15:87-113.

- Gleick, P.H. 2001. “Global water: Threats and challenges facing the United States. Issues for the new U.S. administration.” Environment, 43(2):18-26.

- Gleik, P.H., Wolff, G., Chalecki, E.L., Reyes, R. 2002. The New Economy of Water: The Risks and Benefits of Globalization and the Privatization of Fresh Water. Pacific Institute. Oakland, California.

- Hall, D. 2001. Water in Public Hands. Public Services International Research Unit. London, UK.

- Id21 Insights. 2001. Issue 37: Tapping the Water Market: Can Private Enterprise Supply Water to the Poor. Sussex, UK.

- United Water (2003)