Vapor pressure (Environmental Law & Policy)

Contents

- 1 Vapor pressure

- 1.1 Volatility of liquids

- 1.2 Calculating vapor pressures with the Antoine equation

- 1.3 Vapor pressures and normal boiling points of liquids

- 1.4 Units of vapor pressure

- 1.5 Vapor pressure of liquid mixtures

- 1.6 Vapor pressure of solids

- 1.7 Relative humidity

- 1.8 Vapor pressure terminology used in meteorology

- 1.9 Atmospheric water vapor

- 1.10 References

Vapor pressure

Vapor pressure (also referred to as the equilibrium vapor pressure), is the pressure of a vapor in equilibrium with its liquid or solid phase.[1][2] At any given temperature of a specific substance, there is a pressure at which the vapor phase of that specific substance is in thermodynamic equilibrium with its liquid or solid phases — i.e., when the rates at which molecules escape from and return into the vaporizing liquid or solid are equal. This is the vapor pressure of the specific substance at that temperature.

The vapor pressure of a substance increases with increasing temperature.

Volatility of liquids

The vapor pressure is an indication of a liquid's evaporation rate. It relates to the tendency of molecules and atoms to escape from a liquid or a solid. Any substance with a significant vapor pressure at temperatures of about 20 to 25 °C (68 to 77 °F) is very often referred to as being volatile.

Relative volatility is a measure that compares the vapor pressures of the components in a liquid mixture of chemicals. This measure is widely used in designing large industrial distillation, absorption and other separation processes that involve the contacting of vapor and liquid phases in a series of equilibrium stages.[3][4][5] In effect, it indicates the ease or difficulty of separating the more volatile components from the less volatile components in a liquid mixture.

Calculating vapor pressures with the Antoine equation

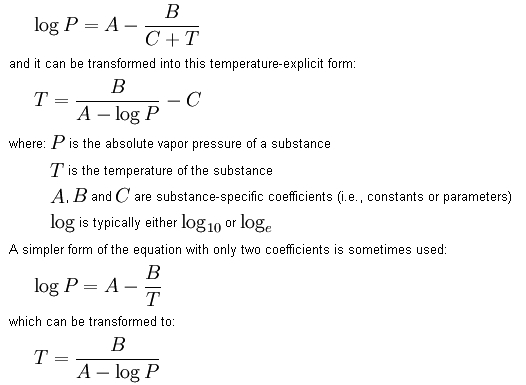

The Antoine equation[6][7] is a mathematical expression of the relation between the vapor pressure and the temperature of pure substances. The basic form of the equation is:Vapor pressures and normal boiling points of liquids

The atmospheric pressure boiling point of a liquid (also known as the normal boiling point) is the temperature at which the vapor pressure equals the ambient atmospheric pressure. With any incremental increase in that temperature, the vapor pressure becomes sufficient to overcome atmospheric pressure and lift the liquid to form bubbles inside the bulk of the liquid. Bubble formation deeper in the liquid requires a higher pressure, and therefore higher temperature, because the fluid pressure becomes higher than atmospheric pressure as the depth increases.The higher is the vapor pressure of a liquid at a given temperature, the lower is the normal boiling point (i.e., the boiling point at atmospheric pressure) of the liquid.

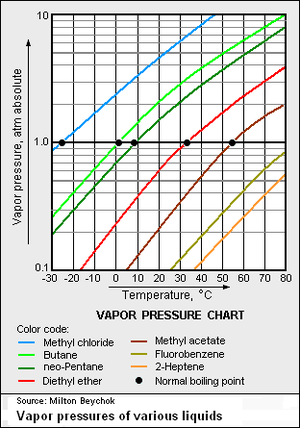

The vapor pressure chart to the right has graphs of the vapor pressures versus temperatures for a variety of liquids.[4] As can be seen in the chart, the liquids with the highest vapor pressures have the lowest normal boiling points.

For example, at any given temperature, methyl chloride has the highest vapor pressure of any of the liquids in the chart. It also has the lowest normal boiling point (– 26 °C), which is where the vapor pressure curve of methyl chloride (the blue line) intersects the horizontal pressure line of one atmosphere (1 atm) of absolute vapor pressure.

Although the relation between vapor pressure and temperature is non-linear, the chart uses a logarithmic vertical axis in order to obtain slightly curved lines so that one chart can graph many liquids.

Units of vapor pressure

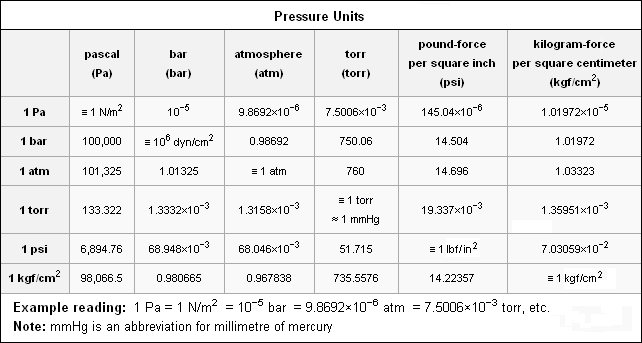

The international SI unit for pressure is the pascal (Pa), equal to one newton per square mete (N · m–2 or kg · m–1 · s–2). The conversions to other pressure units are:There is no consensus in the technical literature about whether the name/unit torr should begin with a capitol letter - as in "Torr" or simply "torr". Both the United Kingdom's National Physical Laboratory (see Pressure Units) and New Zealand's Measurement Standards Laboratory (see Barometric Pressure Units) use "torr" as the name and as the symbol. An extensive search of the website of the U.S. National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) found no such clear-cut definitions. Therefore, this table uses "torr" as both the name and the symbol.

Vapor pressure of liquid mixtures

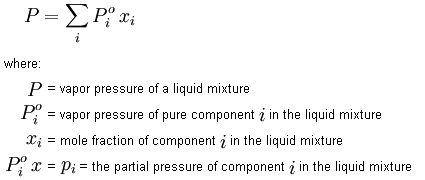

Raoult's law gives an approximation to the vapor pressure of mixtures of liquids.[1][2] It states that the vapor pressure of a liquid mixture is equal to themole-fraction-weighted sum of the vapor pressures of the mixture's pure components:Raoult's law is applicable only to ideal liquids and to components that are fairly similar such as benzene and toluene, hexane and heptane or o-xylene and p-xylene.Systems that have vapor pressures higher than indicated by the above equation are said to have positive deviations. Such a deviation suggests weaker intermolecular attraction than in the pure components, so that the molecules can be thought of as being "held in" the liquid phase less strongly than in the pure liquid. An example is the azeotrope of approximately 95% ethanol and water. Because the azeotrope's vapor pressure is higher than predicted by Raoult's law, it boils at a temperature below that of either pure component.

There are also systems with negative deviations that have vapor pressures that are lower than expected. Such a deviation is evidence for stronger intermolecular attraction between the constituents of the mixture than exists in the pure components. Thus, the molecules are "held in" the liquid more strongly when a second molecule is present. An example is a mixture of chloroform and acetone, which boils above the boiling point of either pure component.

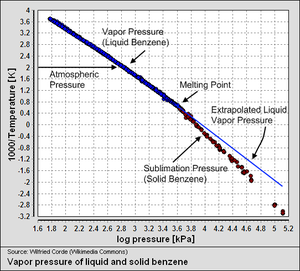

Vapor pressure of solids

All solid materials have a vapor pressure which, for most solids, is very low. Some notable exceptions are naphthalene, ice and dry ice (carbon dioxide). The vapor pressure of dry ice is 5.73 MPa (56.5 atm) at 20 °C which would cause most sealed containers to rupture.Due to their often extremely low values, measurement of the vapor pressure of solids can be rather difficult. Typical techniques for such measurements include the use of thermogravimetry and gas transpiration.

The vapor pressure of a solid can be defined as the pressure at which the rate of sublimation of a solid matches the rate of deposition of its vapor phase.

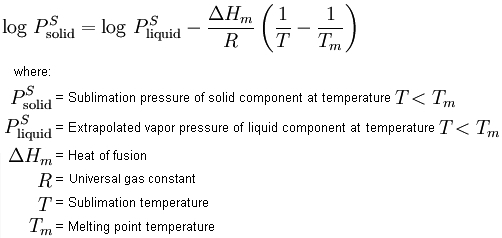

There are a number of methods for calculating the sublimation pressure (i.e., the vapor pressure) of a solid. One method is to calculate sublimation pressures[8] from extrapolated liquid vapor pressures if the heat of fusion is known. The heat of fusion has to be added to the heat of vaporization to vaporize a solid. Assumingthat the heat of fusion is temperature-independent and ignoring additional transition temperatures between different solid phases, the sublimation pressure can be calculated using this version of the Clausius-Clapeyron equation:

gives a fair estimation for temperatures not too far from the melting point. This equation also shows that the sublimation pressure is lower than the extrapolated liquid vapor pressure (ΔHm is positive) and the difference increases with increased distance from the melting point.

Relative humidity

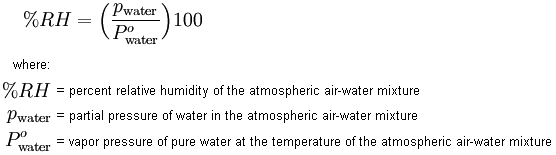

The relative humidity of the atmospheric air is the ratio, often expressed as a percentage, of the partial pressure of water in the atmosphere at some observed temperature, to the vapor pressure of pure water at this temperature.[9] It may be expressed as:At 100 percent relative humidity, the atmospheric air is said to be saturated with water. That occurs when the partial pressure of the water in the air, pwater, is equal to the vapor pressure of pure water at the air temperature, Powater.

Given the wet-bulb temperature and the dry-bulb temperature of the atmosphere, which are readily measured by using a sling psychrometer, the relative humidity can be obtained from a psychrometric chart.[4]

Vapor pressure terminology used in meteorology

The terminology defined and discussed in this article is the terminology used extensively by chemists, chemical engineers and others.

The terminology used in the field of meteorology is unique to that field of science and it defines vapor pressure and similar terms quite a bit differently than is done in this article. For example, the American Meteorological Society (AMS) uses the following definitions:[10]

- Vapor pressure: The portion of the total air pressure exerted by the water vapor component of air. (That would be the partial pressure of the water vapor in the air using the terminology defined in this article.)

- Saturation vapor pressure: The maximum vapor pressure in a sample of air at a specific temperature. (That is not the meaning of "saturation vapor pressure" as defined in this article. In the terminology defined in this article, it can be said that air at a specific temperature is saturated when the partial pressure of the water in the air is equal to the vapor pressure of pure water at that specific temperature. In other words, when relative humidity is 100%.)

Atmospheric water vapor

Water vapor in the atmosphere is classified as a potent greenhouse gas. it has a much higher warming potential than carbon dioxide, and is typically present in much higher concentrations. Water vapor in the atmosphere, of course, is naturally occurring, deriving from plant evapotranspiration, animal respiration and evaporation from soil and surface water bodies. However, some man made activities also generate atmospheric water vapor, e.g. certain agricultural activity, deforestation, and some industrial processes.References

- Neil D. Jesperson (1997). Chemistry. Barron's Educational Series. ISBN 0-8120-9503-0.

- Robert G. Mortimer (2008). Physical Chemistry. 3rd Edition. Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-370617-3.

- Henry Z. Kister (1992). Distillation Design. 1st Edition. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-034909-6.

- R.H. Perry and D.W. Green (Editors) (1984). Perry's Chemical Engineers' Handbook. 6th Edition. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-049479-7.

- J.D. Seader and Ernest J. Henley (1998). Separation Process Principles. Wiley. ISBN 0-471-58626-9.

- What is the Antoine Equation?. Chemistry Department, Frostburg State University, Maryland.

- R.K. Sinnot (2005). Chemical Engineering Design. 4th Edition. Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 0-7506-6538-6.

- Bruce Moller, Jürgen Rarey and Deresh Ramjugernath (2008). "Estimation of the vapour pressure of non-electrolyte organic compounds via group contributions and group interactions". J.Molecular Liquids 143 (1): 52-63.

- Relative Humidity. IUPAC Compendium of Chemical Terminology (Electronic version)

- AMS Glossary of Atmospheric Terms. American Meteorological Society website.