Sub-regional scenarios for Africa's future: Northern Africa

Contents

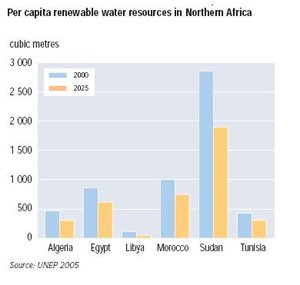

- 1 Introduction The doors we open and close are our choice.(Source: J.C. Mohamed-Katerere) The scenarios for this sub-region focus on the future trends of freshwater resources, as the challenges associated with the availability of freshwater are likely to increase in the future. The current and estimated 2025 levels of renewable water resources in the countries of the sub-region are illustrated in Figure 1. Water stress and scarcity is a growing problem. The available annual water resources per inhabitant vary substantially between different countries, as shown in Figure 3. In terms of internal water resources, it is the poorest sub-region in Africa, accounting for only 1.2 percent of the region’s total internal water resources, but it is also the sub-region with the highest access to external water resources (63 percent) due to the Nile. Agriculture (Sub-regional scenarios for Africa's future: Northern Africa) is the main water consumer, accounting for more than 88.2 percent of water uses. Chapter 4: Freshwater (Sub-regional scenarios for Africa's future: Northern Africa) examines the current state and trends of these resources, and the key pressures placed on them.

- 2 Policy lessons from the scenarios

- 3 Further reading

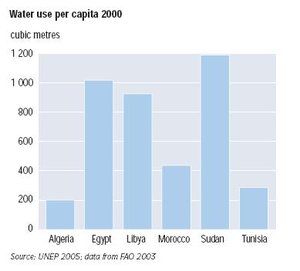

Introduction The doors we open and close are our choice.(Source: J.C. Mohamed-Katerere) The scenarios for this sub-region focus on the future trends of freshwater resources, as the challenges associated with the availability of freshwater are likely to increase in the future. The current and estimated 2025 levels of renewable water resources in the countries of the sub-region are illustrated in Figure 1. Water stress and scarcity is a growing problem. The available annual water resources per inhabitant vary substantially between different countries, as shown in Figure 3. In terms of internal water resources, it is the poorest sub-region in Africa, accounting for only 1.2 percent of the region’s total internal water resources, but it is also the sub-region with the highest access to external water resources (63 percent) due to the Nile. Agriculture (Sub-regional scenarios for Africa's future: Northern Africa) is the main water consumer, accounting for more than 88.2 percent of water uses. Chapter 4: Freshwater (Sub-regional scenarios for Africa's future: Northern Africa) examines the current state and trends of these resources, and the key pressures placed on them.

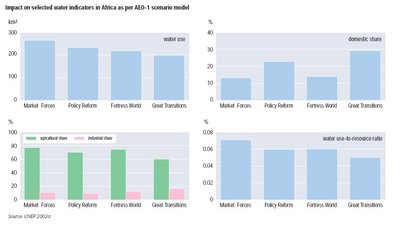

The Africa Environment Outlook 1 (AEO-1) report presented the impacts in key water resource indicators: water use, domestic share, agricultural and industrial share, and water use-to-resource ratio (Figure 18).

Market Forces scenario

Figure 1: Per capita renewable water resources in Northern Africa (Source: UNEP 2005)

Figure 1: Per capita renewable water resources in Northern Africa (Source: UNEP 2005) In the context of globalization and the opportunities international trade brings, Northern Africa seeks to export more goods to Europe and to the rest of Africa. Agricultural products are among the goods identified for increased exports, but they must meet the standards of the target markets. The private sector takes the lead in opening up new foreign markets. New product standards require regulation of the quality of irrigation water as well as fertilizers and other chemicals used in agriculture. This has positive impacts on the quality of soil, shallow groundwater and drainage water.

Competition for water resources between the production of food for local consumption and export increases. The private sector, with larger landholdings, bigger investments and stronger influence on local government, competes with poor small farmers for the limited water resources. The private sector is encouraged to adopt integrated water resource management (IWRM) focusing on conjunctive use of surface and groundwater resources. However, there is overharvesting of groundwater resources, leading to accelerated decline in the groundwater table and salinization of underground water.

Similar competition exists between the other main water users, namely industry and municipalities. The industrial sector increasingly focuses on exports, as greater profits can be made through these markets than in the local market. The large volumes of untreated industrial wastewater pose high risks to the environment, and in particular heavy metals and noxious chemicals are the main lethal pollutants. Increasing levels of water and air pollution create new levels of environmental and social stress, especially because many are dependent on the reuse of water. The vulnerability of poor people and urban dwellers increases.

As part of their economic reform, the Northern African governments privatized some of the public services, including water supply and sanitation. The private companies who run the services cannot offer these at the same low tariffs as were offered when the facilities were under public operation, as these had been highly subsidized. Thus, the tariffs for water supply and sanitation increased and many low-income people can no longer afford these services. This reform, that was intended to increase the availability of safe water, has the opposite effect. The qualities of the services have not improved significantly as a result of privatization, due to low investment and the absence of effective regulation through monitoring and enforcement. Despite these problems the pressure on some Northern African governments to treat water as an economic good is increasing. The agricultural sector is under continuous threat to have some of its “free” water allocated to other sectors that pay for water. The governments continue to oppose water pricing to protect small and poor farmers, but this policy is more rewarding to the private estate farms that enjoy the use of the free vital resource while selling their agricultural products at high market prices.

There are at least three ongoing problems as a result of this policy approach:

- Pollution of water from poorly treated industrial effluents, untreated sewage, run-off of agricultural chemicals, and mining wastes constitute a growing problem.

- Unsafe drinking water, combined with poor household and community sanitary conditions, is a major contributor to disease and malnutrition, particularly among children.

- Contaminated wastewater is often used for irrigation, creating significant risks for human health and well-being.

Policy Reform scenario

Figure 3: Impact on selected water indicators in Africa as per AEO-1 scenario model (Source: UNEP 2002a)

Figure 3: Impact on selected water indicators in Africa as per AEO-1 scenario model (Source: UNEP 2002a) Given the critical role water resources play in development and the increasing problems of water scarcity and stress related to high population growth, the sustainable management of water resources becomes an important policy focus. This is particularly important as the potential for finding new water sources is very limited. The reality is that most of the water required to meet the new demands must come from water saved from existing uses, and consequently demand management is adopted.

Demand management focuses on physical water savings and also economic savings, through increasing water-use efficiency, reducing water pollution and minimizing irrecoverable water losses. Most countries adopt comprehensive reforms of water policies. Such reforms are not easy because long-standing practices, and cultural and religious beliefs, have treated water as a free good. Additionally, powerful interests benefit from the existing system of subsidies and administered allocations of water.

One policy reform aimed at improving efficiency is the increased and active participation of users in the management and planning of water resources. Some Northern African countries have already established water-user organizations, but this has not been the case with all users. The activities of these organizations are continuously reviewed, building on the experiences gained, with a clear target of promoting more rational and efficient use of this vital resource. The improved and fairer access to water resources results in higher levels of social equity, and better opportunities for poor farmers.

Institutional reform of the public sector, which has become overly bureaucratic, receives increasing attention and promises long-term progress in improving performance and hence water-use efficiency. Reforms include reorganization of irrigation agencies into a semi-independent or public utility mode, applying financial viability criteria to irrigation agencies, franchising rights to operate publicly constructed irrigation facilities, and strengthening accountability mechanisms. Following the success of other countries, control of water demand through pricing is adopted by some countries in Northern Africa, but with some caution. The internal conflict and unrest in some countries make this issue very sensitive. Nonetheless, the results are encouraging. Urban and industrial water consumption is reduced, resulting in saving some valuable freshwater.

The reduction in water consumption and consequently the reduced quantities of sewage and wastewater relieves the pressure on the water treatment plants. Because many countries still dispose of treated and untreated wastewater in the northern lakes and in the Mediterranean Sea, improving the quality of this water can have positive impacts on the biodiversity dependent on these water bodies.

But the high prices of urban water and sanitation leave many poor people more vulnerable and insecure. Savings made by the state in privatizing this service are negated by increased costs in the health sector. Consequently, further reforms are introduced. Scaled tariffs are applied to reduce the costs to small consumers and make large consumers pay more. Savings in industrial water use are also achieved through restrictive water licenses, the introduction of water-saving technologies and subsidized financing for investment in water-saving processes. In addition, industries are encouraged to use more recycled water.

The value of groundwater is recognized and tighter controls are imposed on its use. Quantity-based control mechanisms include well and pump permits that grant the right to install and operate a well of a particular capacity, and pumping quotas that specify a fixed annual rate of extraction for each water user. Pumping permits for new wells also impose size and spacing specifications to attempt to optimize extraction rates. The overall objective is to benefit from water resources while at the same time preserving their quality and sustainability.

The subsidies on energy prices (e.g. electricity, diesel, gasoline) are gradually reduced; the aim of this is to discourage over-pumping of groundwater due to cheap energy costs. In countries where farmers pump water from canals to their fields this also discourages unnecessary or wasteful use of surface water. There are some disadvantages, though. The increased prices of diesel raise transportation costs which in turn raise commodity prices in the local markets.

Some general trends are evident in this scenario:

- Some countries seek to increase the use of Nile water and they focus on integrating their development projects and improving cooperation. Groundwater-recharging schemes are adopted in some while in others there is a focus on drought management.

- New laws are passed which set penalties for quantitative and qualitative water misuse.

- Extensive public campaigns are launched to educate the people about the water resources problem.

- A legal basis for controlling water pollution already exists in all Northern African countries, but the laws and regulations have mostly been unenforceable. The regulations are amended to be more realistic and to rely on incentives rather than restrictions. More industries comply with the amended regulations, leaving industrial waste cleaner and less polluted.

Fortress World scenario

This scenario is characterized by pronounced social, economic and environmental inequities between various groups of people. The elite, wealthy and generally better-off groups enjoy monopoly and full control of all services, resources and important economic activities. Poor people are deprived of the most basic services and resources, and generally lack opportunities to improve their quality of life.

At the national level, all Northern African countries focus on utilizing their internal water resources without paying much attention to external resources. This does not seem to cause a serious problem to the Maghreb countries, whose water resources mostly originate from inside their boundaries with very limited transboundary exchanges. Egypt and Sudan continue relying heavily on the Nile waters. Lack of cooperation with the rest of the Nile riparian countries threatens the sustainability of the river flows, and peace within the sub-region. With external technical and financial support, the upper Nile countries embark on building large numbers of small dams for utilizing some of the river’s water. The dams have limited capacities, yet any reduction in the river flows reaching downstream countries could have huge negative impacts on development.

Despite increased demand for water, the opportunities for developing new water resources or adopting demand management techniques are not explored by the dominant wealthy groups, who do not feel the strain of the problem. The distribution of resources per capita is skewed among the various groups, with the wealthy taking the lion’s share of the resources, especially land and water. Water allocation to the various water-user sectors follows a similar pattern. Being industry-driven, the elite allocate more water to the industrial sector, depriving irrigated agriculture from a much needed vital input. Urban water supplies are concentrated in the areas of the wealthy groups. Water use in those areas is wasteful, generating large volumes of sewage and wastewater. Groundwater use is dominated by the wealthy groups in the society who can afford the costs of extraction. Overuse of fossil groundwater depletes those resources and endangers their sustainability. Large declines in the water tables are observed and well salinization becomes a problem. Accordingly, the cost of groundwater extraction rises and this is translated into similar increases in the costs of the final products for which this water is used.

Low-income activities, such as subsistence agriculture and basic industries, are forced to use marginal and unsafe water. Municipal water supplies in the poor areas are largely unsafe, creating high risks for the majority who cannot afford good health care. The low-tech industries in the poor areas are forced to recycle and re-use water. But with very limited financial and technical resources, they are unable to recycle and re-use water safely. The food industries are the most vulnerable as the use of unsafe water in their products can lead to food-transmitted diseases.

The quality of agricultural drainage and sewage water deteriorates due to repeated re-use of the water. Industrial waste also adds to the acuteness of the problem as industries dispose of mostly untreated wastewater. Weak monitoring and enforcement of laws encourages the wealthy industry investors not to treat their industrial waste before disposing it in watercourses and public sewage networks. Water heavily polluted with industrial waste is sometimes reused in downstream areas, creating serious environmental damage and health risks in those areas.

Investment in water-development projects is directed towards meeting the needs of elite groups, who make the investments. These projects usually have limited scope and target small groups of people. The general public do not benefit from these projects, apart from income earned as a result of supplying cheap labour. State-run utilities and services suffer from underinvestment, causing the services to further deteriorate and the infrastructure to run down. This is evident in the rapid silting-up of the reservoirs of the large number of dams in the Maghreb countries. But the larger cost to the economies is the lost resources from leakages, high water evaporation in large reservoirs and pollution.

In summary, freshwater shortages continue to be experienced in most Northern African countries, albeit with varying degrees. The key aspects of this scenario are:

- A focus develops on using internal water resources with little attention being given to exploring the potential of external resources.

- The improper management of water increases pollution, resulting in the degradation of surface water and increasing the incidence of soil erosion and salinization.

- Water shortages and pollution limit development and perpetuate economic and social inequities, leaving many people increasingly vulnerable.

Great Transitions scenario

Box 1: Facing the challenge of limited groundwater resources...(Source: UNEP, 2006)

Box 1: Facing the challenge of limited groundwater resources...(Source: UNEP, 2006) The water scarcity problem currently existing in Northern Africa is given the full attention and consideration of the governments of the sub-region. As a result a variety of measures to ease the problem are adopted. Besides carefully managing the conventional water resources in a sustainable way, non-conventional techniques such as rainfall harvesting, desalination and water recycling are employed. Increased industrialization helps lower the cost of these new techniques and they become affordable to many sectors.

In addition, all the countries adopt IWRM programmes to effectively manage all available water resources. They are implemented through developing national legislative and institutional frameworks. Intergovernmental cooperation in the management of the Nile waters is improved, and extended beyond existing users to include all riparian countries. The NBI achieves remarkable goals, planning and implementing win-win water resources development projects to most riparian countries. Water master plans are drawn around IWRM as the key solution to the problem. Integrated water resources management frameworks which integrate the technical, hydrological, economic, environmental and social aspects are formulated and implemented under the appropriate institutional frameworks. There is also increased sharing of best practice. Experiences gained by the Northern African countries in implementing IWRM are shared at the sub-regional level, and this increases the use of adaptive management which has important gains for sustainable management.

National plans are prepared for rehabilitating the ageing agricultural system, the main water user. Groundwater abstraction is controlled. Water re-use is abandoned and is replaced with water recycling. Due care is given to the problem of loss of agricultural land due to soil salinization, erosion and degradation. Soil rehabilitation schemes include banning of the use of chemicals and replacing them with organic fertilizers. A switch to cash crops for export assists the move to organic fertilizers. Research focuses on producing new crop varieties that are more drought- and salt-tolerant, have shorter life cycles and require less water. The water-use efficiency of the agricultural sector is closely monitored. As a result, less agricultural drainage water is generated, reducing the pollution it causes to the Mediterranean Sea and the other water bodies where drainage water is disposed of.

Food security is no longer a key issue in government policies. As the economies of many Northern African countries improve, their ability to import food from the global market increases without the need for debts or loans. Water allocations to the various sectors are reviewed, with more shares allocated to the industrial and municipal uses. The flourishing industry is more efficient in water use in terms of economic returns per unit of water. Agricultural reform through land consolidation proves to be beneficial to all those involved:

- Larger landholdings for the farmers change the nature of their agriculture from subsistence to commercial. Consequently, they are able to invest more in their irrigated agriculture by buying better inputs and hiring more experienced labourers or moving to mechanization. The end result is a more efficient irrigated agriculture. The whole rural community also benefits from higher agriculture returns. More children in the rural areas now attend school to the secondary level. The services in the rural areas noticeably improve, with more people having access to safe drinking water and sanitation, better health care, etc.

- Large numbers of the unskilled labourers who used to work in agriculture are absorbed by the growing industry. They receive on-job training which raises their skills and make them a more productive force in the society. Their living standards also improve, with their family members benefiting from better education, health care, housing, access to safe drinking water and sanitation, etc.

Water pumping is still a major environmental concern in many of the Northern African countries as the majority of the pump sets are diesel-driven. Gas emissions, water and soil pollution by fuel and oil, and noise pollution are some of the negative impacts. The use of electric motors for water pumping is promoted in order to ease the problem. Incentives include reduced motor and spare parts prices and low electricity tariffs. There are fears, though, that such policies could encourage overuse of water resources, especially groundwater. Control and monitoring of groundwater use ensure that such fears do not become reality.

Policy lessons from the scenarios

Given the hydrological status of Northern Africa the management of freshwater resources will remain a challenge, with major implications for the overall prosperity of the sub-region – in terms of the opportunities for both economic growth and improving human well-being. All the scenarios point to the need for management approaches that are based on IWRM and acknowledge the links between surface and groundwater. Closely related to this is the transboundary nature of the available resources. Here the policy lessons are clear: to improve opportunities throughout the sub-region and to reduce the possibility of conflict, cooperative approaches must be adopted.

All economic development choices are dependent on a reliable water supply. The scenarios reveal various policy options for promoting this including market mechanisms, management focused on improving efficiency, more equitable access rights and increased public participation. Each of these policy options has opportunities and costs.

Further reading

- El-Fattal, L., 2006. IDRC-Supported Research for Better Water Governance Through Community-Based Water Management Approaches. WADImena News, 14 February.

- FAO, 2003. AQUASTAT Information System on Water in Agriculture. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome.

- UNEP, 2006. Africa Environment Outlook 2.

|

|

| Disclaimer: This article is taken wholly from, or contains information that was originally published by, the United Nations Environment Programme. Topic editors and authors for the Encyclopedia of Earth may have edited its content or added new information. The use of information from the United Nations Environment Programme should not be construed as support for or endorsement by that organization for any new information added by EoE personnel, or for any editing of the original content. |