Serengeti (Agricultural & Resource Economics)

Contents

Serengeti

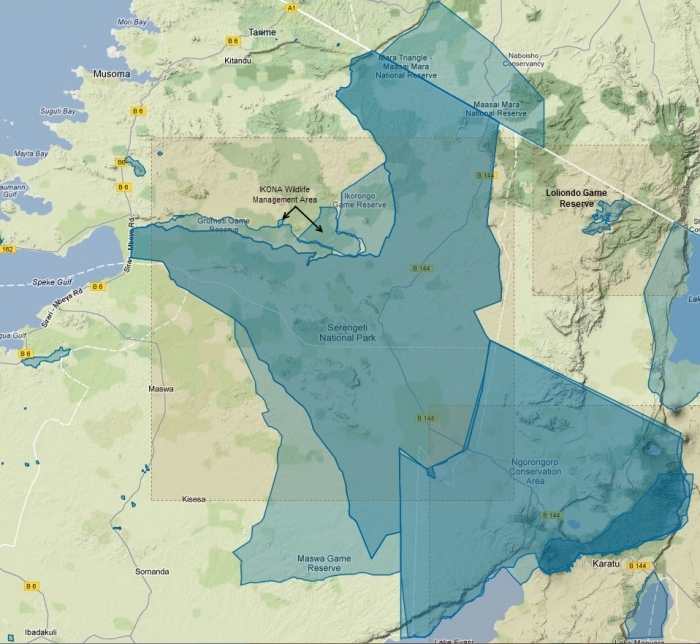

The Serengeti is an expansive plain immediately south of the equator in eastern Africa covering over 30,000 square kilometres (12,000 square miles) east of Lake Victoria in northwestern Tanzania and southwestern Kenya which is home to the largest herds of grazing mammals in the world.

The Serengeti is an expansive plain immediately south of the equator in eastern Africa covering over 30,000 square kilometres (12,000 square miles) east of Lake Victoria in northwestern Tanzania and southwestern Kenya which is home to the largest herds of grazing mammals in the world.

In the heart of these wide-sweeping grasslands and associated Acacia-Commiphora woodlands, the world’s most spectacular migration of large mammals occurs each year. An estimated 1.3 million Blue wildebeest, 200,000 Plains zebras, and 400,000 Thomson’s gazelles traverse the Greater Serengeti ecosystem, triggered by cyclical wet and dry seasons. The area included withinin the migration zone is about 25,000 square kilometers (10,000 square miles).

The world famous Serengeti National Park and the Ngorongoro Conservation Area are here in the Tanzanian part of the plains; both designated as World Heritage Sites and Biosphere Reserves. The smaller Kenyan Masa Mara National Reserve protects part of the northern reaches of the Serengeti. A large portion of the eastern Serengeti falls within the multiple-use Ngorongo Conservation Area.

The chief threats to the ecoregion are the same as other savanna areas in the region, poaching of large mammals for body parts and meat, and expansion of pastoralism and agricultural use of the area with associated loss of tree cover.

The name Serengeti is derived from the Maasai language, Maa; specifically, Serengit means endless plains.

On the eastern edge of the Serengeti is Olduvai (Oldupai) Gorge, where some of the earilest humanoid Fossils have been discovered, and as a result is often called "the cradle of mankind."

Physical geography

Location

The Serengeti is just south of the equator, extending between latitudes 1o and 3o30' S and longitudes 34o and 36o E.

The physical boundaries of the Serengeti are:

- In the north - the Isuria Escarpment and Loita Plains of Kenya,

- In the east - the Loita Hills and Nguruman Escarpment of Kenya; and the Gol mountains and Crater Highlands of Tanzania. Beyond these higlands lies the Albertine rift (or the Western Rift Valley), part of the Great Rift System.

- In the south - the Lake Eyasi escarpment and an area of rocks and dense miombo woodlands

- In the west - the Seeregeti does not reach Lake Victoria because of cultivation (in the northwest) and rocks and dense woodlands (in the southwest), execept for the "western corirdor" between Mbalageti and Grumeti rivers which extends alomost to Speke Gulf.

Topography and geology

The Serengeti Plain sits atop an elevated plateau that slopes west to Lake Victoria. The highest part of the Serengeti is on the eastern plains near the Gol Mountains (1850 meters), with the lowest elevations toward Speke Gulf (920 meters) The majority of the ecoregion falls between 900 and 1200 meters (m).

West of Seronera, the entire area is underlain by Precambrian basement rocks (up to 2.5 billion years old) that have been deformed, then eroded over hundreds of millions of years. Ultisols and alfisols lay over basement rocks, with patches of vertisols close to Lake Victoria.

The hills in the ecoregion are formed of more recent sedimentary rocks, and some are recent volcanics (Igneous rock) with some active volcanoes. In many areas late Precambrian outcrops of granitic gneisses and quartzite project from the surface as inselbergs (locally called kopjes).

The underlying soils and materials of the Serengeti plains are comprised of volcanic ash derived from a number of local volcanoes. The dormant caldera of Ngorongoro, the Kerimasi Volcano and Mt Lengai (last eruption in 1966) have all contributed volcanic ash to these soils (vertisols). These soils have characteristic plant communities, distinguishing the ecoregion from its neighbors. Topographically, the ecoregion is comprised of flat to slightly undulating grassy plains, interrupted by scattered rocky areas (Kopjes) which are parts of the Precambrian basement rocks protruding through the ash layers.

A rock outcropping, or kopje, on the Serengeti plain. Source: Steven Pastor

Hydrology

The Serengeti is drained by several rivers that from from the higher earea in the east and north into Lake Victoria, and thus the region is part of the the Nile watershed.

The Mara River rises in the of Mau Escarpment of Kenya north of the Serengeti, flowing southwest through Masai Mara Game Reserve before turning west at the Kenya-Tanzania border and continuing through Serengeti National Park and on to Lake Victoria at Mara Bay.

The Mbalageti and Grumeti rivers, and their tributaries, drain much of the central Serengeti before flowing nearly parallel through the western corridor of Serengeti National Park to Speke Gulf of Lake Victoria.

Climate

The climate of the Serengeti is a result of several factors including the prevailing regional climate pattern, Lake Victoria, and local topography.

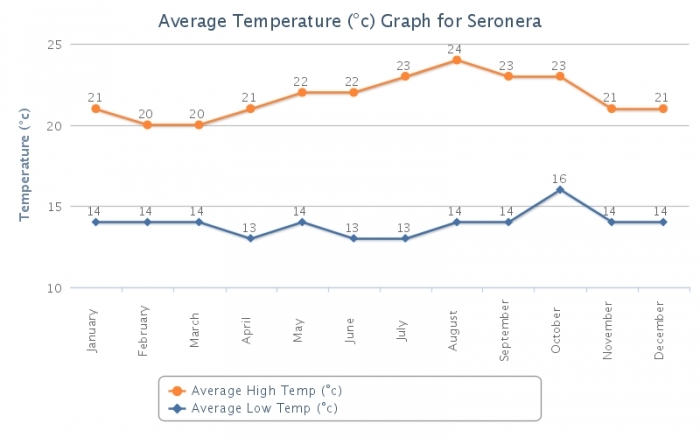

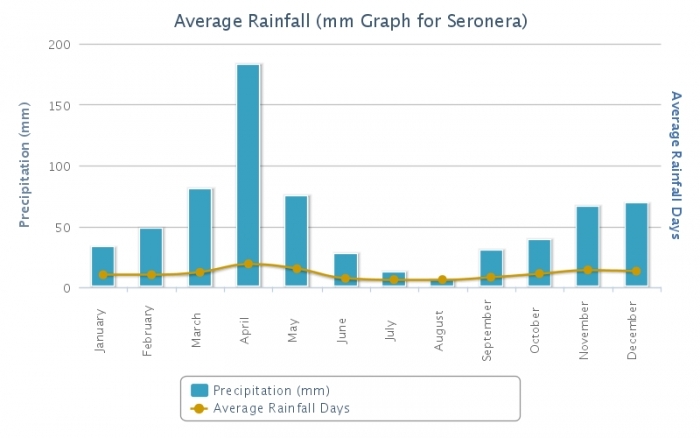

Because of its location just south of the equator, the climate is fairly steady throughout the year. Temperatures are moderate with mean maximum temperatures as high as 30°C at lower elevations and as low as 24°C at the highest parts of the ecoregion. Mean minimum temperatures are between 9° and 18°C, and normally between 13° to 16°C. At Seronera, the following figures show average temperature an rainfall.

Source: World Weather Online.

The rainfall is seasonal, falling in a bimodal pattern. The longer duration rains occur from March to May, and the briefer rains from November to December. Mean rainfall is 600 to 800 millimeters (mm) annually through most of the region. Extremes include 500 mm in the dry southeastern plains and 1200 mm in the northwestern region located in Kenya. Rainfall is variable, such that the short rains may fail in a given year or rain may occur between the two rainy seasons, thereby joining the two.

The Crater Highlands that reach 3000 m in altitude and bound the Serengeti in the southeast create a rain shadow to the northwest. As a result the southeast of the Serengeti receives far less rain (approximately 500 mm) than the northwest (about 1200 mm), where the rainy seasons also end later. The southeastern plains are considered arid, the north as subhumid, and the rest semiarid.

This annual cycle of climate drives the great migration cycle of wildebeests, plains zebras and Thomson’s gazelles.

Protected areas

Much of the Serengeti is under some level of protection, including:

| Tanzania | Km2 | miles2 |

| 14,763 | 5,700 | |

|

Ngorongoro Conservation Area (extends beyond the plains and includes the Crater Highllands) |

8,288 | 3,200 |

| Maswa Game Reserve | 2,200 | 850 |

| Grumeti Game Reserve | 412 | 160 |

| Ikorongo Game Reserve | 603 | 233 |

| Loliondo Wildlife Management Area | 400 | 154 |

| Ikona Wildlife Management Area (proposed) | ||

| Kenya | ||

| Masi Mara National Reserve | 1,510 | 583 |

| 28,176 | 10,880 |

Source: protectedplanet.net

Serengeti National Park. Source: Tim Smith/YouTube

Ecology

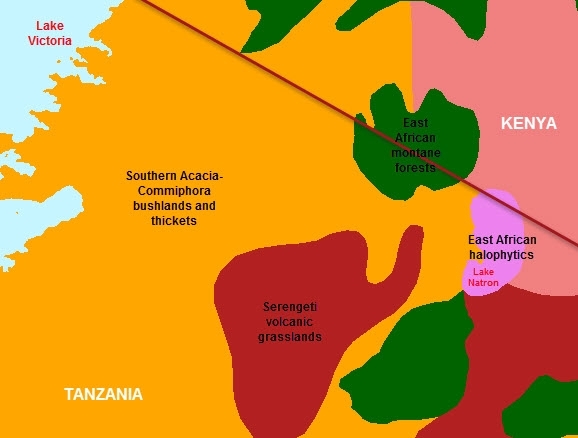

The entire region is often referred to as the Seregeti-Mara ecosystem. However, two World Wildlife Fund ecoregions cover most of the Serengeti: Southern Acacia-Commiphora bushlands and thickets and Serengeti volcanic grasslands.

In the Southern Acacia-Commiphora bushlands and thickets ecoregion, the predominant plants include species of Acacia, Commiphora, and Crotalaria and the grasses Themeda triandra, Setaria incrassata, Panicum coloratum, Aristida adscencionis, Andropogon spp., and Eragrostis spp. Within Tanzania, the ecoregion is bisected by two patches of Serengeti Volcanic Grassland and patches of East African Montane Forest. The volcanic grasslands are an integral habitat of the greater Serengeti ecosystem. However, the grasslands are considered a separate ecoregion due to their unique grassland communities, found only on the fine volcanic soil, or vertisol.

During the long dry season (August to October), the grasslands can become extremely parched, and many of the trees and bushes lose their leaves. Fires occur naturally in the ecosystem. Both fire and elephant browsing play an important role in converting dense thicket and bushland into grassland. However, a large number of fires are started by pastoralists to promote new vegetative growth for their livestock.

With so many large herbivores, grazing is clearly a significant disturbance in this ecoregion. Different herbivores tend to feed on different graze species and components, enabling grazing sequences by different ungulate species at the landscape scale. For example, Grant’s gazelle prefer herbs and shrub foliage, wildebeest usually feed on a wide variety of nutritious, short grasses, and topi tend to eat long grass leaves. Studies here have shown that when ungulate grazing is removed, plant species composition and growth form changes relative to those under grazing, and that some important grass species (e.g., Andropogon greenwayi) eventually disappear in the absence of this disturbance. Other studies have found that the grasses found in grazed patches are more productive than ungrazed patches, and that these patches are able to support larger concentrations of herbivores than stocking rates would suggest.

The great migration

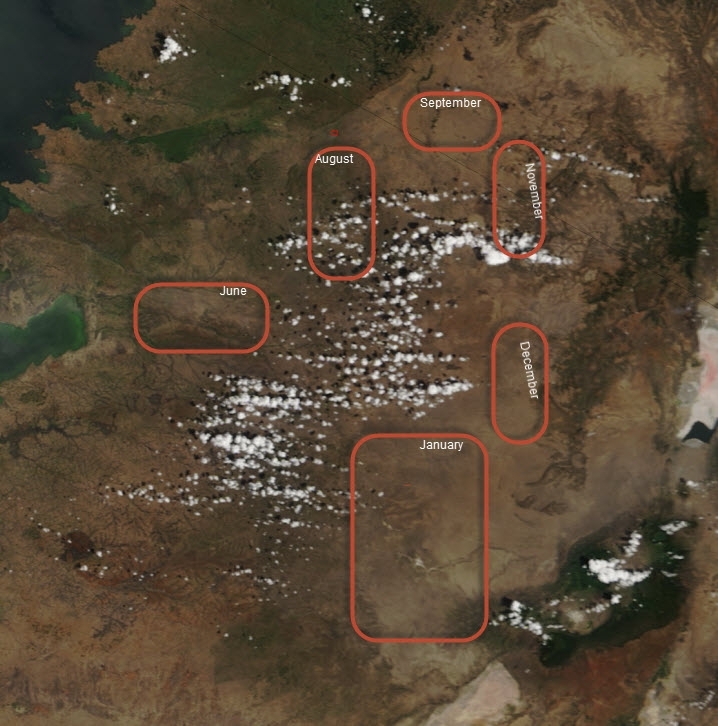

In the heart of these wide-sweeping grasslands and associated Acacia-Commiphora woodlands, the world’s most spectacular migration of large mammals occurs each year. Wildebeests, plains zebras, and Thomson’s gazelles traverse the Greater Serengeti Ecosystem, triggered by cyclical wet and dry seasons.

Although populations fluctuate, there are an estimated 1.3 million blue wildebeest (Connochaetes taurinus), 200,000 plains zebra (Equus burchelli), and 400,000 Thomson’s gazelle (Gazella thomsoni) migrating between the Serengeti volcanic grasslands ecoregion and the Southern Acacia-Commiphora bushlands and thickets ecoregion each year.

These species do not migrate in one synchronized trek; rather the migration occurs in waves in response to the area’s seasonal rainfall, and resulting available grazing. The plains zebras arrive in an area first and begin grazing the coarse grass stalks. Wildebeests follow and graze on the smaller grass leaves and forbs visible after the zebras consume coarse material. Thomson’s gazelles, with their smaller mouths and higher relatively energy demands, then graze the small, tender new shoots. During the wetter half of the year (December to June) the animals use the short-grass plains of the Serengeti volcanic grasslands ecoregion. During the long dry season, the animals move northward into the grasslands, savannas and shrublands of the Southern Acacia-Commiphora Bushland and Thicket. During the driest months (July to October), the animals move to the extreme northern section of the ecoregion, into Kenya’s Masai Mara game reserve. Both the distance and direction of the migration varies in relation to fluctuations in ungulate population density and rainfall patterns. Human-wildlife conflicts often occur when the ungulates traverse areas outside the gazetted protected areas, moving into agricultural lands.

Wildebeest migration. Source: National Geographic.

A large number of associated mammalian predators are also involved in these movements. Contrary to popular belief, the Serengeti’s large predators account for no more than one-third of all deaths among the migratory herds. Thousands of years of predator-prey coexistence have resulted in a number of anti-predator life history traits among prey species. Many live in large herds, to reduce individual chance of falling victim to predators. Some animals, such as Thomson’s and Grant’s gazelles (Gazella granti) may hide their young until they are strong enough to flee an attack. Most large prey species living in big herds with precocial young (e.g. wildebeest, topi (Damaliscus lunatus) and buffalo (Syncerus caffer)) display highly synchronous birthing seasons. Most large predators are territorial, and only hunt until satiated. Since young are at their most vulnerable in the first month or so of their lives, the chances of being killed are much lower for each calf if they all offspring are born within a short time period. Calves of these species born outside of the synchronized birth period seldom survive.

Biodiversity

The Serengeti National Park provides lists of of the most notable animals and plants found on the Serengeti which are reproduced here:

Animals

|

Primates

Ungulates (28 species) Aardvark: Orycteropus afer Hyraxes

Pro Boscids

Odd-toed ungulates

Even-toed ungulates

Spiral horned bovines

'Duikers': Grey duiker: Sylvicapra grimmia Dwarf Antelopes

Gazelle

Reedbuck and allies

Horse-like Antelopes

Topis and allies

Hares: Cape Hare: Lepus capensis Rodents

|

Carnivores

Mongooses

Hyaenids, Hyaenidae and Protelinae

Cats

Dogs

Weasels

Scaly Anteaters: Ground Pangolin: Smutsia temminckii Bats: Order Chiroptera Insectivores

Birds

Reptiles

|

Wildebeest crossing river. Source: Stefan Swanepoel

BBC Nature Documentary hosted by Michael Praed and published by BBC broadcasted as part of BBC Natural World series in 2005. Source: BBC/You Tube

Plantlife

Savanna Vegetation

Serengeti National Park is made up of grassland and woodland, plains, kopjes, and marshes; all of which comprise a savanna.

Savanna is a general term for any type of semi-arid land from open grassland to woodland and all mixtures of grass and trees in between. Savannas cover one quarter of the worlds land surface and can support more animals than any other land type.

One common feature of savannas is fire. Unless savanna grass is completely consumed by animals or frozen, it will occasionally burn. With the potential to have massive numbers of resident animals and frequent fires, savannas are dynamic landscapes and tend to change rapidly in time. This makes them both very interesting scientifically, and important to understand for management purposes.

Commonest plant species

Sausage tree (Kigelia africana)

This large tree is spread sparsely throughout Serengeti. It produces characteristic long (about one meter), succulent, poisonous fruits that drop from the tree and release seeds as the pulp rots. The vine-like fruit stalks can be seen for months after the fruits are dropped. There is a dry bush joke that the worst place to camp is under a Sausage tree .. if the five kilogram fruits don't crush you, then the elephants will as they come to collect the fruits. There is a widespread local belief that sausage tree fruits, when hung in your hut, will ward-off whirlwinds.

Strangler fig (Ficus thonningii)

The Strangler Fig begins life as a small vine-like plant that climbs the nearest large tree and then thickens, producing a branching set of buttressing aerial roots, and strangles its host tree. An easy way to tell the difference between strangler figs and other common figs is that the bottom half of the strangler is gnarled and twisted where it used to be attached to its host, with the upper half being smooth. The strangler fig is a common tree on kopjes and along rivers in the Serengeti; two notable massive fig trees near Serengeti are: the "Tree Where Man was Born" in southern Loliondo, and the "Ancestor Tree" near Endulin, in Ngorongoro. Both specimens are significant for the local Maasai peoples.

Wild Date Palm (Phoenix reclinata)

Palms are monocotyledons, the veins in their leaves are parallel and unbranched, and are thus relatives of grasses, lilies, bananas and orchids. The wild Date Palm is the most common of the native palm trees, occurring along rivers and in swamps. The fruits are edible, though horrible tasting, while the thick, sugary sap is made into palm wine. The tree offers a pleasant, softly rustling, fragrant-smelling shade; the sort of shade you will need to rest in if you try the wine.

Candelabra Euphorbia (Euphorbia candelabrum)

(Yes, the names are supposed to reversed) The Candelabra tree is a common species in the western and Northern parts of Serengeti. Like all Euphorbias the Candelabra breaks easily and is full of white, extremely toxic latex. One drop of this latex can blind or burn the skin. Traditional people plant the tree as cattle fencing, as predators will not attempt to push their way through the dense and poisonous stems. Some circles of Candelabra can be seen in the park, where seasonal dwellings existed before the establishment of the park.

Commiphora (Commiphora africana)

Commiphoras can easily be distinguished from Acacia tree species by the Commiphora's peeling, papery blue/yellow bark. These trees occur throughout Serengeti, and are the dominant species in the eastern part of the park. Local medicine makes use of the bark, roots, and berries for a variety of treatments, including stomach complaints, liver problems, colic children, and rashes. While there are several species of Commiphora in Serengeti, Commiphora africana is the most common.

Yellow fever tree (Acacia xanthophloea)

The Yellow Fever Tree is a common site in Serengeti in wet areas of black-cotton soil, such as in riparian zones. Early settlers in Kenya and India knew that malaria was more common near standing water, but blamed the Yellow Acacias there instead of mosquitoes; thus the name "yellow never tree".

Umbrella tree (Acacia tortilis)

The tree that has come to represent Africa. Acacia tortilis arches dramatically over the savanna throughout Serengeti. The seedlings of this tree are favored by elephants and cannot survive bush fires, so only twice in the past one hundred years have tortilis trees been able to grow. As such all of the tortilis trees in Serengeti are either 100 or 20 years old.

Whistling thorn (Acacia drepanolobium) (Ant-galled Acacia)

Tap a "drep" and you are in for a surprise. This odd-looking tree has hard, hollow spheres at the base of its thorns, filled with biting ants. The tree actually encourages these ants by both providing homes and food in special flower-like structures called "extra-floral nectaries". These tree grow in abundance wherever the soil is saturated.

Desert date (Balanites aegyptia)

The Balanites tree is often confused with Acacia trees, but can easily be identified by its green thorns. This tree produces a date-like nut that is tasty both raw and roasted (with cinnamon). The green thorns are rumored to be photosynthetic, so the tree is both happy and alive even without its leaves.

Toothbrush tree (Salvadora persica)

The toothbrush tree is a low bush with characteristic long, arching shoots. These shoots, when green, are cut by locals and used as toothbrushes. First, they chew on the end until it resembles a normal toothbrush, and then they brush their teeth with it, spitting out the fragments of wood all the while. It may sound unpleasant, but their smiles tell of a job well done.

Red Grass (Themeda triandra)

Turning a dark reddish color as it dries, Themeda is one of the main grass species in the long-grass plains and woodlands of Serengeti. This grass normally grows as a dense bunch, though on the long-grass plains it can become the dominant grass and grows widely spaced like a field of wheat. Wildebeest eat Red grass, though it is consumed generally after more palatable grass species are exhausted.

Pan Dropseed (Sporobolus ioclados)

This Sporobolus species is one of the two dominant species on the short grass plains along with Digitaria macroblephora. Both species grow in a dwarf form, so that they are difficult to recognize. The hardpan layer in the soil prevents grasses from producing deep roots, and high levels of wet season herbivory (Herbivore) combine to produce these dwarfed grass forms.

Red Dropseed (Sporobolus festivus)

The grass species is not common in Serengeti, but it is included here, because it is so amusing to say: pronounce the name out loud .. "Sporololus festiiiiiiivus"! Named for its "festival-like" arrangement of seeds, the species typically grows in association with red grass in the long grass plains, and as a thin perimeter ring around many kopjes.

The El-Nino Flower (Hibiscus cannabinus)

During the last El-nino rains, this plant grew in abundance throughout Serengeti, thus acquiring the local name of "El-Nino" flower. An annual, it grows most years along rivers or in wet-season boggy areas throughout East Africa. Watch out if you are taking a picture of hibiscus flowers; most of the species in the genus have poisonous hairs that break off in your skin and cause irritation and lots of grumbling.

The Mexican Poppy (Argemone mexicana)

This is an alien species in Serengeti, recently introduced southwest of Ngorongoro with a shipment of wheat seeds. Along with other invasives such as prickly pear (Opuntia sp.), and custard oil (Rhyciuus sp.) the Mexican Poppy may pose a very serious threat to the survival of the Serengeti Ecosystem. During the 1960's Prickly Pear ruined thousands of square kilometers of Australian savanna ranchland, while the Mexican Poppy is making some areas near Karatu unfarmable, competing with both crops and native plants. The threat of an invasive species changing the vegetation structure of Serengeti and thus the wildlife appears both real and immediate; Karatu is only eighty kilometers from the entrance gate of Serengeti National Park and individuals have already been found within the park.

Maasai man in the eastern Serengeti, October 2006. Source: Steve Pastor/Wikimedia Commons

Maasai man in the eastern Serengeti, October 2006. Source: Steve Pastor/Wikimedia Commons

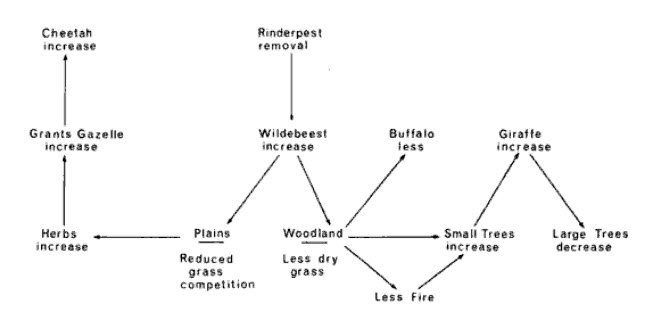

Rinderpest

In 1890, an infectious disease known as rinderpest (German for "cattle plague") arrived in East Africa and within two years killed 95% of the buffalo and wildebeest and at least half of the cattle in the region before recovery began. Rinderpest outbreaks swept across other parts of the world, include recurrances in Africa, before and after the East Africa outbreak. It was eventually eraticated worldwide, with the last case reported in Kenya in 2001. However, Rinderpest had long-term social and ecological consequences for the Serengeti.

The cattle-herding Masai people were dramatically impacted with devastating poverty and starvation. Coupled with smallpox and impacted of colonialism, the Masai population dropped by as much as 60% during this period.

The ecological impacts of rinderpest rippled with the ecosystem with large declines in species dependent on the ungulates. These ranged from tsetse fly (which transmited blood based diseases like sleeping sickness) to lions (some of which turned to humans and established their popular reputation "man-eaters"). The dramatic drop in both grazing animals and humans allowed thickets to establish themselves on what had been and are again today grasslands or cultivated areas.

The later recovery of ungulates in the early twentieth century also revived the tsetse fly which slowed or even prevented the return of humans to parts of the landscape. In the 1930s, mechanized bush-clearing methods reversed the revival of the tsetse fly and the numbers of people and cattle (also helped by a vacine for rinderplast).

Rinderplast had important, but far less dramatic, outbreaks in 1917-18, 1923, and 1938-40; particularly impacting young "yearlings." A comprehenive immunization effort directed at cattle occured in the early 1950s had good initial results, but the disease resurfaced in 1957-59. By 1962 it had largely disappeard from wildebeast; and by 1963 in buffalo. The populations of both species began to recover rapidly in the 1960s.

The impact of rinderpest disapearance (simplfied) is shown in the following figure:

Source: A.R.E Sinclair in Serengeti: Dynamics of an Ecosystem.

Humans on the Serengeti

This area is of great interest and importance in terms of human evolution. Olduvai Gorge on the eastern edge of the Serengeti is the site of the discovery of the 1.75 million-year-old remains of Australopithecus boisei and Homo habilis by Louis and Mary Leakey.

Originally, the presence of the tsetse fly, which carries sleeping sickness, limited the development of much of the ecoregion. Its partial eradication has made human settlement possible throughout much of the area.

Outbreaks of rinderpest dramatically impacted with devastating poverty and starvation for the cattle-herding Masai people. Rinderpest coupled with smallpox and impacted of colonialism, reduced the Masai population by as much as 60% at the end of the nineteenth century. Continued outbreaks led to conflict between pastoralists and wildlife managers over buffer zones between protected areas and grazing lands.

Today, much of the land outside the protected area system has been converted to agricultural and intensive-use livestock areas. Within the Serengeti ecosystem in Tanzania, local people and their livestock utilize resources in multiple-use areas, conservation areas outside of the gazetted national parks.

While Masai pastoralists occupy the Ngorongoro Conservation Area, there are no people living within the Serengeti National Park. However, the western frontier of this Park has a dense resident population, growing at 4 percent a year. Not only is the human population increasing, but there is also a concomitant increase in livestock numbers, and much of the area is being converted into cropland, while the demand for land rises. Although agriculture is the main source of income, many people have been attracted to the area by the wildlife resources and tourism opportunities the park presents. At present, it is estimated that 200,000 animals within the Serengeti National Park are killed annually, in poaching operations that have graduated from subsistence to commercial levels. It is hoped, however, that schemes to give local communities legal rights to manage the wildlife around their villages will reduce this. There are also plans to channel more money earned from tourist activities within the park back into the community, as the contribution from tourism to the local economy has been relatively low.

In the past, severe elephant poaching has occurred in many areas. This has largely been stopped due to CITES restrictions on ivory trade from declining elephant populations, and the efforts of the Tanzanian government, which brought in the army to solve some of the worst problems. Poaching of black rhinoceros has been even more severe, and the species has essentially been extirpated from most of the ecoregion, except for a few heavily protected sites.

Outside of protected and multiple-use areas, almost all the land suitable for large-scale agriculture has already been converted. This conversion reduced the number and variety of corridors available for wildlife to move between protected areas. For example, the number of available corridors between Tarangire National Park and nearby protected areas has decreased from 30 to 4 viable corridors since the early 1970’s. Overall, the most damaged [[habitat]s] in the ecoregion are located close to the mountains that rise from the plains. These areas provide a reliable source of rainfall and water for irrigation and are important for both large-scale commercial and subsistence agriculture. The areas close to Lake Victoria are mainly agricultural and have higher-than-average human population densities.

Expansion of the human population into the remaining habitats outside protected areas, and the increase of dryland agriculture (e.g. for tobacco) could also have a major effect on the habitat. Tobacco is a particular problem as it not only needs space for growing, but also requires fuelwood for drying. Even in the larger blocks of protected areas, competing demands between wildlife and burgeoning human populations near the borders is leading to increased conflict for resources and space.

Charcoal is made from many of the woodland tree species and is heavily used for daily cooking needs as well as for drying tobacco. The cutting of woody materials for firewood and charcoal production threatens almost all areas that have any type of human settlement. Tree regeneration is commonly very low in densely populated areas. Woodland removal results in loss of many of the small ungulate species as well as birds, reptiles and small mammals. Illegal taking of bushmeat, both for subsistence and trade, is a growing concern. An increasing reliance on bushmeat as a major protein source has resulted in localized depletions of many wildlife species, especially in areas adjacent to protected areas.

One of the largest problems associated with the [[growing] human population (Population growth rate)] is the bushmeat trade. Subsistence hunting for meat has been a part of the ecosystem since early hominid evolution. However, increasing markets for bushmeat for both rural and urban people is leading to the depletion of several antelope species. This problem is most severe in the areas outside and adjacent to the protected sites. Hunting and taking of bushmeat is an ever-increasing and serious threat to all animals throughout the ecoregion.

Uncontrolled trophy hunting within some of the Tanzanian hunting concessions may be a problem. Quota-setting and enforcement need to be carried out over an ecoregion scale, rather than by individual hunting blocks. Illegal trophy hunting and poaching are not currently large problems, partly because most black rhinoceros have been already been killed. Careful monitoring and patrolling activities need to be continued, however, to protect the large elephant populations and the few remaining black rhinoceros.

Serengeti sunset. Source: Vincent van Zeijst

References

- Sinclair, A.R.E., Serengeti Past and Present, in Serengeti II: dynamics, management, and conservation of an ecosystem, edited by A.R.E. Sinclair and Peter Arcese, The University of Chicago Press, 1995 ISBN 0226760316

- Sinclair A.R.E., The Seregeti Environment, inSerengeti: Dynamics of an Ecosystem, Editors, Sinclair, A.R.E. and M. Norton Griffiths, University of Chicago Press. 1979, ISBN 0226760294

- Serengeti III: Human Impacts on Ecosystem Dynamics, Editors, Sinclair, A.R.E.,Craig Packer, Simon A. R. Mduma, and John M. Fryxell, University Of Chicago Press, 2006, ISBN 0226760332

- Africa's Great Rift Valley. Nigel Pavitt. 2001. Page 122. Harry N. Abrams, Incorporated, New York. ISBN 0-8109-0602-3.

- Serengeti National Park

- Trees of Kenya. 1989. T.C. Noad and A. Birnie. Self Published, Box 40034 Nairobi, Kenya. With assistance of Kul Graphics, Nairobi, Prudential Printers, Nairobi, and General Printers, Nairobi.

- Collins Guide to the Wild Flowers of East Africa. 1987. Sir Michael Blundell. William Collins Sons & Co. Ltd. London.