The "Heroic Age" of Antarctic Exploration

The "Heroic Age" of Antarctic Exploration

Exploration of the Antarctic - Part 6

See also Chronology of Antarctic Exploration.

The declaration of the Sixth International Geographical Congress (1895) that ". . . exploration of the Antarctic Regions is the greatest piece of geographical exploration still to be undertaken. . ." lead to a surge in Antarctic activities—fifteen major expeditions to Antarctica over the following twenty-two years. Nationalistic and personal rivalries were played out for the recognition and honors that came from the worldwide attention given to the Antarctic exploration through newspapers. With rescue from the outside world difficult or impossible, individual heroism was on significant display during these expeditions as many died in the harsh conditions of Antarctica.

Antarctic expeditions were not all about bravado and glory; they included scientific teams that gathered data on meteorological conditions, oceanic currents, terrestrial magnetism, geological and geographical features, and ecology, as well as collection of geological, botanical, and zoological samples. It was this latter aspect of the expeditions, often overlooked by a public fascinated by personalities and the race to the South Pole, that provided the basis for modern exploration of the Antarctic.

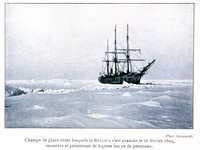

The Belgica Antarctic Expedition (1897-1899), led by Belgian naval officer Adrienne de Gerlache and including Norwegian Roald Amundsen, began as a summer scientific expedition on the west side of the Antarctic Peninsula (Anvers Island, de Gerlache Strait in the Palmer Archipelago were among the geographical legacies.) However, de Gerlache pushed the expedition south late into the season, and in March 1898, the Belgica became locked in sea ice; drifting with the ice floe for thirteen months in the Bellinghausen Sea before getting free.

Unprepared as the expedition was for a forced overwinter inside the Antarctic Circle (including 63 days without sun light), it was a difficult time with physical and mental impacts on the men. However, the scientific members collected data for an entire Antarctic year (including hourly meteorological readings) that ran to 10 volumes when published. Also, the Belgica expedition learned much about the challenges of overwintering that would be used by later expeditions.

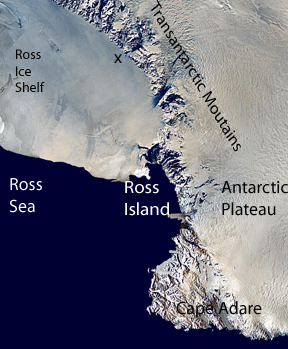

As the Belgica was struggling to break free of its ice prison, Carsten Borchgrevink returned to Cape Adare, as head of the Southern Cross Expedition. This expedition planned to winter ashore (a first) and collect meteorologic and magnetic data over a full twelve month period. After being dropped ashore at Roberson Bay with prefabricated huts, supplies and seventy five dogs, they established camp, while their ship, the Southern Cross, returned to New Zealand. After a difficult winter, the men attempted inland exploration using dogs drawn sledges (another first in Antarctica), but were limited by the mountains that separate the Cape Adare region from the Antarctic interior.

Blocked from the interior, the expedition reunited with their ship in January 1900, and sailed south along the coast of Victoria Land charting and naming various geographical elements to Ross Island and the Great Ice Barrier. Borchgrevink followed Ross's path along the edge of the Ice Barrier to an sloping inlet. There they landed and traveled south ten miles further to set a new "Farthest South" record at 78°50'S. On the return north, the expedition stopped to take measurements for a more precise location of the magnetic south pole within Victoria Land.

In the following year, three expeditions descended on Antarctica, in three very different regions.

The German Gauss Expedition (1901-3) led by experienced Arctic explorer and scientist Erich Dagobert von Drygalski, sailing south of the Kerguelen Islands, charted a region of coast that he named Kaiser Wilhelm II Land (87°E-91E°). Kaiser Willhelm II Lan was situated between the previously observed regions of Wilkes Land and Enerby Land. Following the unfortunate precedent set by the Belgica Expedition, the Gauss became trapped in ice (this time for fourteen months) during which it had the time to carryout significant exploration (including the extinct volcano Gaussberg) and scientific work (identifying 1,440 species of animal life living in Antarctic waters.)

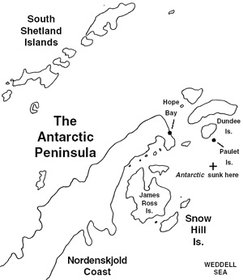

The Swedish Antarctic Expedition (1901-4), led by Otto Nordenskjöld suffered a harsher fate when it tried to conduct charting and scientific work on east of the northern tip of the Antarctic Peninsula. After Carl Anton Larsen dropped off Nordenskjöld and his overwintering party on Snow Hill Island in January 1902, a productive period of work passed. However, on returning to pick up the team, Larsen's ship, the Antarctic, was blocked by pack ice. In late December 1902, Larsen sent three men to Nordenskjöld on foot from Hope Bay at the northern tip of the peninsula. Unfortunately, this party could not reach Snow island and returned to Hope Bay. Meanwhile, Larsen had tried to break through the ice toward Snow Island only to become trapped. The ice crushed the Antarctic forcing Larsen to abandon ship and settle his men on Paulet Island. The expedition now composed of three separated groups, were forced to survive the winter of 1903, as best they could with little hope about whether they might be rescued. In October, as spring arrived, the Hope Bay party moved south, met members of Nordenskjöld's party probing north, and all returned to Snow Island. On November 4, Larsen's team arrived at Hope Bay by rowing boat and found a message indicating the plan to reach Snow Island. Finally, luck turned for the expedition in the form of an Argentinian rescue ship, the Uruguay. On November 8, the Uruguay, picked up the Snow Island group and two days later, Larsen's team at Paulet Island.

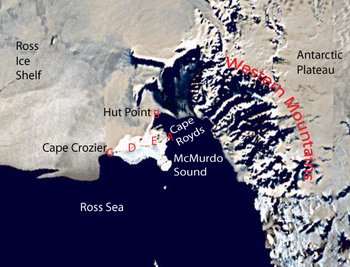

While the German and Swedish expeditions were making the most of major setbacks that forced unexpected overwinters, a British expedition led by naval officer Robert Falcon Scott was having a much more satisfactory time. The Discovery Expedition (1901-4) was well-funded and provided with a military command structure under Scott. It followed on the heels of the privately funded Southern Cross Expedition but after a stop at Cape Adade moved south to establish its main base at Hut Point on Ross Island adjacent to the Great Ice Barrier in February 1902.

The first summer season was primarily a learning period and preparation for the winter. In November, Scott, Earnest Shackleton, and zoologist Edward Wilson began an attempt for the South Pole, or at least a new Farthest South record with dog-pulled sledges and the use of supply depots established along the way, often with the help of other expedition members. However, they were not well trained in the use of dogs and made slow progress. On November 21, they discovered the Transantarctic range of mountains to the west of the ice shelf. As they continued south, they adopted the common practice in polar exploration of killing the weakest dogs as food for the other dogs. By late December, scurvy and snow blindness began to effect the men and a halt was called. Before, turning north Scott ordeedr Shackleton to stay with the dogs, while he and Wilson, continued a few miles further to set a new Farthest South record of 82°17'S, 350 miles from base. The return march was aided by the use of an improvised sail on the sledge, but was slowed by the failing physical condition of Shackleton as he succumbed to scurvy. After 93 days, the three returned to base on February 3, 1903. A month later, Scott ordered Shackleton back to England on a relief vessel before the second overwintering. A growing rift between the men would be reflected in future Antarctic exploration.

While southern journey was underway, a party traveled around Ross Island to Cape Crozier and discover the Emperor Penguin colony there.

In October 1903, Scott led a nine-man party west toward the mountains of Victoria Land in a effort to reach the south magnetic pole. After ascending the Ferrar Glacier to 9,000 feet altitude and he reached a vast icy Antarctic Plateau. Scott, Edgar Evans and William Lashly continued west for another eight days and came to within 70 miles (110 km) of the calculated location of the magnetic pole. On the return journey, the group discovered the first snow free dry Antarctic valleys.

Other journeys had been taken while the main westerly exploration was under way, including onto the Ice Barrier, to Cape Crozier and the Koettlitz Glacier. Also, significant meteorologic, magnetic, and zoologic study was undertaken. In February 1904, the expedition departed.

In February 1903, while Scott, Shackleton and Wilson were recovering from their Farthest South journey, Drygalski and the Gauss were breaking free of their ice prison, and Larsen was abandoning the Antarctic—as it was being crushed in the ice—a converted whaler, the Scotia, was carrying the Scottish National Antarctic Expedition under the leadership of William Spiers Bruce into the Weddell Sea. Following a sudden drop in temperature and the formation of ice pack around the ship, the Scots turned wisely north at 70°25'S and returned to the South Orkney Islands. Bruce's team establish a weather station in the South Orkneys on Laurie Island and took systematic meteorologic data through the winter. In the spring, while some stayed behind to continue data collection, the Scotia, sailed to Buenos Aires where Bruce offered the weather station as a permanent addition to Antarctic science to the British representative there—they declined. Bruce went to the Argentines and they accepted. When the Scotia returned to the South Orkneys, three Argentines accompanied the expedition to take over the running of the first permanent weather station in the Southern Ocean.

In late February 1904, as the Discovery Expedition was leaving the Ross Sea, the Scotia headed south into the Weddell Sea. At 72°18'S 17°59’W, the Scotia was confronted by an ice barrier that they tracked south for 150 miles, sounding the depths of shallow sea, dredging rocks and observing petrels, all evidence that the ice wall fronted land, that they named Coats Land after the main financial backers of the expedition. Also, it was the discovery of the eastern side of the Weddell Sea. After being temporarily trapped by ice, the Scotia, turned north on March 13.

When news of the disappearance of the Swedish Antarctic Expedition reached Europe in mid-1903, a private French expedition led by Jean-Baptiste Charcot changed their plans for an Arctic expedition to a rescue mission to the Antarctic. When Charcot arrived in Buenos Airies in mid-November, he discovered that Nordenskjöld's group had just been rescued by the Argentines. Charcot continued south and overwintered at Booth Island off the west coast of the Antarctic Peninsula conducting scientific studies. In the spring the geographic work resumed and 600 miles of coastline charted before the ship struck a rock in January (1905) and forced the expedition to head north.

In late 1908, Charcot returned with a new expedition to the same area, overwintering 1909 at nearby Petermann Island. In 1910, Charcot headed farther south along the coast past Alexander Island and discovered new land, that he named Charcot Land. It was later determined to be an island. Charcot continued to chart the icy coastline to about 124°W (the Bellinghausen Sea and the Amundsen Sea) before turning north.

Earnest Shackleton returned from the Discovery Expedition determined to return south and surpass the accomplishments of Scott. Shackleton's vision of reaching the geographical south Pole, the magnetic south pole, and conducting extensive science gained private backing. He headed south in command of the Nimrod Expedition in 1907. Scott requested that Shackleton not use Ross Island as a base as he wished to reserve it for his own return expedition. Shackleton reluctantly agreed but found, on his arrival in the area in January 1908, that edge of the Great Ice Barrier was breaking up just where he planned to establish his own base, at the Bay of Whales. The risk of unstable ice persuaded Shackleton to go back to Ross island and establish a base as Cape Royds twenty miles from Hut Point with a land party of 16 men, 8 Manchurian ponies and nine dogs. Also, Shackleton brought along an automobile—a first, and a failure.

On March 10, five members of the expedition reached the 12,447 feet (3,794 m) summit of Mount Erebus.

On October 28, after an uneventful winter, Shackleton, Jameson Adams, Eric Marshall and Frank Wild began their bid for the South Pole using four Mongolian ponies pulling two sledges. Maintaining a faster pace that achieved six years earlier, and able to use the ponies that succumbed as food, the four men reached the edge of the [[Great Ice Barrier]/Ross Ice Shelf] 440 miles from Cape Royds at the start of December and discovered the Beardmore Glacier carving a path through the Transantarctic Mountains. The last pony died on the 100-mile long glacier, but they reached the Antarctic Plateau in late December. By January 9th, the group reached 88°23'S, just 97 nautical/geographic miles or 111 statute miles from the South Pole. As food dwindled—to go further risked death on the return journey—Shackleton turned north. The men were short of food throughout the journey back and beset by dysentery but survived the ordeal. A new Farthest Record had been set, the terrain to the pole determined, and enough learned to guide the ultimate conquest of the pole.

Simultaneous to the South Pole bid, was a effort to reach the magnetic south pole to which Shackleton had assigned three Australian scientists on his expedition, Edgeworth David, Alistair Mackay, and Douglas Mawson. This was accomplished by crossing the Western Mountains (really the portion of the Transantarctic Mountain range along the coast of Victoria Land. Again, glaciers provided the roads through the mountains to the Antarctic Plateau. On January 17, 1909, David, Mackay, and Mawson reached the magnetic pole at 72°15?S 155°16?S (note that it migrates over time) and claimed the region for Great Britain (something that expeditions were commonly doing for their countries.)

In addition, a third party conducted geological studies around the Ferrar Glacier immediately west of Ross Island.

The Nimrod Expedition was in New Zealand on March 23, and returned to Britain in triumph.

The goal of the South Pole remained as did the North Pole. Polar exploration was hugely popular with the public and it was only a matter of time until the goal would be attained. The achievement of the pole came within three years, but at a cost. (see Amundsen and Scott at the South Pole). Also, Shackleton, Douglas Mawson and others had more to contribute before the "Heroic Age" of Antarctic exploration would pass. (see Mawson, Shackleton and the end of the "Heroic Age").

Further Reading:

- To the South Polar Regions, Louis Charles Bernacchi, Hurst and Blackett Limited, 1901 ISBN: 1437440878.

- South Pole: A Narrative History of the Exploration of Antarctica, Anthony Brandt, NG Adventure Classics, 2004ISBN: 0792267974.

- Voyage of the Belica, Adrien de Gerlache de Gomery,(translated by Maurice Raraty), Archival Facsimiles Ltd,1999 ISBN: 1852970545.

- First on the Antarctic Continent, C.E. Borchgevink, C Hurst & Co Publishers Ltd,1980, ISBN: 0905838416.

- The Voyage of Discovery, Robert Falcon Scott, Nonsuch, 2005V.1 ISBN: 1845880579 V.2 ISBN: 1845883772.

- Pilgrims on the Ice: Robert Falcon Scott's First Antarctic Expedition, T.H. Baughman, Bison Books, 2008 ISBN: 0803216394.

- The Heart of the Antarctic: Being the Story of the British Antarctic Expedition, 1907-1909 , Rt. Hon. Lord Shackleton, Basic Books,1999 ISBN: 0786706848.

- Shackleton's Forgotten Expedition: The Voyage of the Nimrod, Beau Riffenburgh, Bloomsbury USA, 2005 ISBN: 1582346119.

- The voyage of the "Why not?' in the Antarctic;: The journal of the second French South polar expedition, jean-Baptiste Auguste Etienne Charcot, 1908-1910, Hodder and Stoughton, 1911

- Exploring Polar Frontiers: An Historical Encyclopedia, William James Mills, ABC-CLIO, 2003 ISBN: 1576074226.

- Index to Antarctic Expeditions, Scott Polar Research Institute, retrieved November 1, 2008

- Antarctica: Exploring the Extreme: 400 Years of Adventureby Marilyn J. Landis, Chicago Review Press, 2001 ISBN: 1556524285.

- Antarctic History, Polar Conservation Organization, retrievedFebruary 16, 2009

- Antarctic History, Antarctica Online, retrieved February 16, 2009

- The Antarctic Circle,retrieved February 16, 2009

0 Comments