Regional scenarios for Africa's future: land

Contents

Introduction Figure 1: Illustrative patterns of the changes over time of key scenario assumptions(Source: UNEP (Regional scenarios for Africa's future: land) )

The interfacing and changes in these key driving forces, as used in the narratives in this chapter, are assumed to take the patterns reflected in Figure 1. The narratives presented in the subsequent sections are based on these patterns of change in the main driving forces.

In order to provide a holistic storyline, the regional and sub-regional narratives have been integrated for some issues while stand-alone sections have been reserved for issues more directly relevant to specific sub-regions. The four regional narratives focus on transboundary aspects and ecosystems at sub-regional and regional levels, and discuss the implications of policy choices for meeting the Millennium Development Goal (MDG) targets by 2025. The analysis is undertaken in the context of the Opportunity Framework (see Introduction). The policy lessons from the scenarios are closely related to the future state of the environment as presented in Section 2: Environment State-and-Trends: 20-Year Retrospective.

Land

Box 1: Factors influencing land-use change in Africa used in the scenario analysis

Box 1: Factors influencing land-use change in Africa used in the scenario analysis(Source: Raskin and others 1999, MI 2002)

The future status of land resources has important development and human well-being implications. Therefore, the substantive analysis of land-use patterns and their implications for sustainable development is crucial. Such analysis requires a long-time frame and needs to incorporate uncertainty. Fundamental uncertainty is introduced both by our limited understanding of human and ecological processes, and by the intrinsic indeterminism of complex dynamic systems that characterize the environment. Outcomes are predicated on policy choices, which are yet to be made, and natural occurrences that are out of the control of humankind. Nevertheless, there is a huge amount of temporal, spatial and socioeconomic land-use information that can form the basis of such analysis.

There are many environmental, technological and socioeconomic factors driving changes in land resources. How these factors evolve will shape the regional and sub-regional development and future opportunities. Box 1 presents a summary of the most important factors that influence the state of land and land-use change in the region. An analysis of how these factors will prevail under each scenario forms the basis of the narratives in this section. Among the factors that are especially important in Africa are: agriculture, forestry, demography, market developments, environmental conditions, social context (including the history of a sub-region) and policies related to land-use planning.

Chapter 3: Land (Regional scenarios for Africa's future: land) considers the current state and major trends affecting land resources. These trends include:

- An increase in agricultural land, both arable and marginal, over the past three decades and a corresponding decrease in forest cover;

- A sharp increase in heavily degraded lands from a combination of drivers and pressures, including desertification, climate change, chemical pollution from industry and agriculture, and armed conflict;

- A diversification in the uses of land resources, including tourism and mining, with demonstrated increased earnings from these sectors.

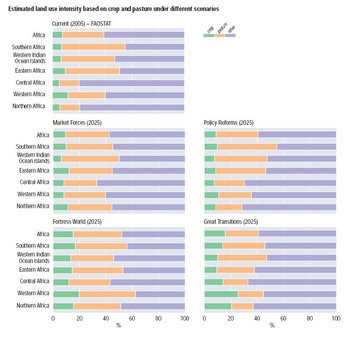

Figure 2: Regional projections of land under irrigation in the four scenarios

Figure 2: Regional projections of land under irrigation in the four scenarios(Source: UNEP)

Other land-use changes, such as increased urban and infrastructural development, have been minimal but will continue to play a significant role in land-resource availability and condition in many parts of Africa. Widespread problems also concern decline in soil fertility, soil contamination, land management and conservation, gender imbalances in land tenure, and conversion of natural habitat to agricultural or urban uses. The threat to land resources posed by invasive alien species (IAS) remains a challenge (see Chapter 10: Invasive Alien Species). Inequitable land distribution patterns remain a problem, as discussed in [[Chapter 3: Land (Regional scenarios for Africa's future: land)]2] and Chapter 12: Environment for Peace and Regional Cooperation (Regional scenarios for Africa's future: land), and this has implications for environmental management and human well-being. Land tenure policies will continue to have an important effect on environmental change. Assessing how these trends will be played out in future, and identifying appropriate responses to mitigate negative impacts, requires considering the major drivers and pressures. The core driving forces include: demography; technology; economy; political and social institutions; climate and environment; culturally determined attitudes, beliefs and behavior; and information and its flow.

The most critical issues for scenario analysis include identifying opportunities for Africa to meet the MDG targets and effectively implement theNew Partnership for Africa's Development Environment Action Plan (NEPAD-EAP) programme areas, addressing desertification and food security. One such opportunity is the expansion of irrigated land, and this resonates well with attempts by Africa to achieve enhanced food security, eradicate poverty and increase the productivity of land-use management. These narratives focus on the opportunities of increasing irrigated land. The key threats addressed, as the storylines unfold, include land tenure and ownership, land degradation (soil fertility, water scarcity, desertification and erosion vulnerability, and salinization), poor agricultural practices, invasive alien species (IAS) and inundation of habitats as a result of damming.

Market Forces scenario

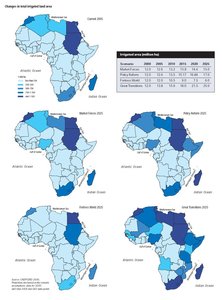

In the Market Forces scenario there unfolds greater than normal demand for agricultural products which in turn results in agricultural expansion, exposing more land to water erosion.

In the course of development, human activity alters the landscape. The dynamics of land change are complex, depending on settlement patterns, agricultural practices, economic growth and natural resource industries. Several key developments shape land use in the Market Forces scenario. These developments relate to human settlements, pastures and rangelands, cropland expansion and land degradation as well as the “built environment.”

The “built environment” encroaches on natural environments (such as forests) and near-natural environments (such as agricultural and grazing land) as populations grow and economies modernize. The settled area per person has been increasing historically and is currently estimated at 0.14 hectares (ha) per capita in Eastern Africa. However, in Southern Africa, per capita land access has dwindled from 20.09 ha in 1985 to 13.16 ha in 2000, and continues to decline. Given the current low population densities and horizontal, as opposed to vertical, settlement, population growth places significant pressure on agricultural lands and valued ecosystems. In the Market Forces scenario, the dominant change at the regional level is the conversion of forest to grazing and pasture land. To a lesser extent, natural forest is lost to expanding areas of built environment, cropland and forest plantations.

The utilization of land for grazing livestock changes for several reasons. The intensity of livestock production (output per hectare) changes in response to changing pasturing practices and improved livestock characteristics from scientific developments. Despite the increased intensity of use, the extent of grazing areas increases in all sub-regions. The increase is at the expense of cropland, forests, and marginal land. Changing pastureland requirements is indicative of trends in land degradation. New agricultural land comes from forest conversion, grazing and rangeland, with the shares varying by sub-regions. In addition, in some sub-regions, agriculture expands onto marginal land requiring considerable input and careful management.

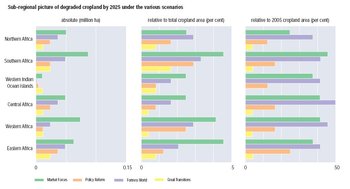

Unsustainable land-use practices can lead to, or exacerbate, various forms of land degradation including wind and soil erosion, soil compaction, waterlogging, salinization and nutrient depletion. In the Market Forces scenario, in all the sub-regions severe degradation is witnessed with more and more agricultural land becoming degraded. This is the result of intensified agricultural practices driven by profit goals. Although attempts are made to protect and partially rehabilitate damaged ecosystems, this is outstripped by the high land degradation rates occasioned by the economic attractiveness of market-based production. The rate of land degradation in the region varies from 25-35,000 ha per year under this scenario. This rate varies from sub-region to sub-region and will intensify after 2015. The land degradation rates are higher than those registered in the past.

In the Market Forces scenario there unfolds greater than normal demand for agricultural products which in turn results in agricultural expansion, exposing more land to water erosion. A shift away from less intensive crop and livestock production to more intensive, but environmentally insensitive, practices leads to a greater risk of water erosion. A greater percentage of land converted to agriculture is evident in Central and Western Africa. The effects of population pressure are greatest in Southern and Eastern Africa. In the long term, the effects of land degradation are reflected in diminished yields and increased deforestation rates. The current upward swing in the quantity of land so severely degraded that it has to be removed from agriculture production continues under the Market Forces scenario. The combined effect of the various driving forces results in changes in land cover and the exposure of more and more land to degradation through erosion. In particular, the area under forest cover declines drastically during the 2005-2025 period.

Policy Reform scenario

The often conflicting goals of providing space for human settlements, protecting ecosystems, and feeding human populations are reconciled through a combination of measures all centered on policy-driven sustainable land use.

The Policy Reform scenario is growth-oriented but assumes a comprehensive policy response to the environmental and social risks associated with land use. The scenario does not assume major deviations from the conventional development paradigm, values and institutional structures, but within those constraints incorporates rapid economic growth, greater distributional equity and vigorous attempts to protect the environment. The definitive reference for this vision is the Brundtland Commission’s report, Our Common Future (WCED 1987).

Change under the Policy Reform scenario ushers in an era of economic growth, based on policies that sustain and expand the land resource base. Comprehensive and coordinated government action is taken in pursuit of this. In this context, an integrated set of land reforms and land management initiatives are crafted and implemented, including economic reform, regulatory instruments, land tenure system changes, social programmes, and technology development for sustainable land use.

The main contours of a Policy Reform scenario comprise high income and economic growth, improving environmental conditions, greater equity and reduced conflicts over land. There is a far greater efficiency of land resource use, more reliance on renewable land resources and less environmental pressure. The often conflicting goals of providing space for human settlements, protecting ecosystems and feeding human populations are reconciled through a combination of measures all centered on policy-driven sustainable land use.

The transition to agricultural sustainability requires a “doubly green” revolution, in which agricultural productivity continues to improve but is coupled with practices that preserve the environmental foundation for the long-term. In this scenario, a campaign for sustainable agriculture is launched, resulting in a gradual shift towards ecologically sound practices rather than the replication of high-input farming. The challenge is to maintain yield improvements at something like Market Forces scenario levels, while avoiding degradation. As part of the pollution-reduction goals of this scenario, fertilizer and pesticide use per hectare decline. To maintain yields, the nutrient requirements of plants must be met and pests kept in check in other ways. Nutrient recycling partly substitutes for fertilizer, for example, by using livestock manure in combined crop-livestock systems and through large-scale composting. The poverty alleviation goals of the scenario support these trends, as increasing income allows farmers to diversify their production. Additional actions needed include the development and application of biotechnology and other research (e.g., disease-resistant varieties), education and training of farmers, land reform, infrastructure development and reform of economic policies. Programmes for sustainable agriculture are carried out in cooperation with farmers and targeted to local needs.

Changes in grazing land for livestock production are the result of various trends. Economic growth pushes the demand for livestock products higher. Agricultural production expands to meet increasing livestock feed demand so as to reduce the need for grazing land, and this approach has the net effect of reducing pressure on forests and other ecosystems. In addition, some improvement in grazing land productivity is evident due to the adoption of modern practices. Similarly, increased investmentsR & D lead to improvements in herd quality. At the same time, policies are adopted to ensure that grazing practices are more sustainable in order to reduce environmental destruction. The transition to sustainable livestock practices can be achieved through a variety of interventions, including by providing information through extension services, and by enforcing overgrazing laws. In arid lands, where the availability of forage can vary greatly from year to year due to climate fluctuations, policies to provide timely access to markets and land can allow producers to cope without overtaxing biomass resources.

Driven by the combination of food and feed requirements, regional cropland area expands by about 20 per cent between 2005 and 2025, a larger increase than the 11 per cent of the Market Forces scenario.

Driven by the combination of food and feed requirements, the regional cropland area expands by about 20 percent between 2005 and 2025, a larger increase than the 11 per cent of the Market Forces scenario. However, because of land and water constraints in many sub-regions, there is considerable variation between and within sub-regions. The largest increases occur in areas where there are the least land and water constraints. This implies more extensive trade in food commodities. In Eastern Africa, where cropland grows by over 40 percent, some of the increase is met by returning to production land held by the government. Regionally, a greater share of the cropland is on rain-fed land than in the Market Forces scenario. Expansion of irrigated land is discouraged by increases in water prices, as countries try to limit the incidence of water stress.

Consistent with the sustainability goals and livelihood strategies discussed in Chapter 1: The Human Dimension, the rate of land degradation slows between 2005 and 2015. Depending on the nature of the land and its use, degradation is reduced through different means:

- Improving drainage and delivery systems for irrigation water can restore irrigated land subject to waterlogging and salinization, and conserve water resources at the same time;

- Nutrient loss from shifting cultivation can be reduced by lengthening fallow periods; and

- Loss of land through water erosion can be reduced by building terraces and using conservation tillage.

Up to 2015, croplands are degraded at a rate assumed to be less than the Market Forces rate. This rate slows down further after 2015. Further opportunities available for redress include integrated land and water resources management; the sustainable management of wetland resources; sustainable agriculture and rural development; technology transfer; and the development of early warning systems and assessment of land degradation. Under this scenario, the establishment of regional and sub-regional early land degradation warning systems are pursued . Efforts by countries to implement NEPAD’s initiatives to combat desertification and land degradation are reflected in land use and land reform policies. Land reform policies take the centre stage through attempts to modernize land use, especially in Southern Africa where obvious imbalances have persisted in land ownership and tenure.

The expansion of the built environment is curtailed in the Policy Reform scenario, as concerns for protecting productive cropland, forests and other ecosystems lead to urban planning policies that favor more compact settlement patterns. This is supported by a higher value being placed on arable lands, as a result of increasing domestic demands and, in some sub-regions, profitable opportunities for increased trade. The preservation of forests and other valued ecosystems is recognized as a key sustainability goal. Specifically, the rate of forest loss gradually decreases in the scenario to zero by 2025 and the extent of forest areas begins to increase thereafter. Between 2015 and 2025, there is net reforestation. This is achieved through forest protection policies and land-use strategies that support more compact settlements, the contraction of grazing lands and land restoration. In this scenario, the amount of forest land set aside as protected areas increases. Increased emphasis is placed on the preservation of established forests and other ecosystems that support biodiversity. Also, opportunities are developed for encouraging the sustainable use of forest products among poor people, such as by granting secure land rights.

Unexploited grasslands and savannah are placed under grazing, especially in Southern Africa. The rapid expansion of the built environment and grazing land that occurs in the period 2005 to 2015 is slowed or reversed between 2015 and 2025. Eventually, agricultural land grows to supply the increasing food demands of countries facing land and water constraints. The successful transition to sustainability requires:

- Widespread awareness of the issues and the conviction that action is necessary;

- Adequate institutions, policies and technologies; and

- Sufficient political will to accept the costs of carrying out the required actions.

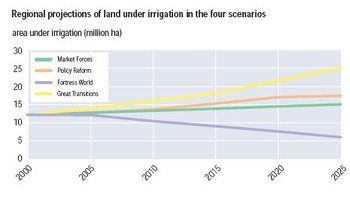

Changes in the Policy Reform scenario are the same for all sub-regions except in Central Africa where the need for irrigation continues to be limited. The scenarios for Northern Africa show essentially the same trends, despite tying irrigation to rice production. In Northern Africa, in the Policy Reform scenario, water-conservation policies increase the cost of water, so irrigation water is increasingly diverted to higher-valued uses, leading to a decrease in the irrigated area. At the same time, the efficiency of application of irrigation water improves. Reduced production is made up in part through increased imports, a strategy often described as one of importing “virtual” water contained in the crops. In the Policy Reform scenario, irrigated area increases from 12.6 million ha in 2005 to 17 million ha in 2025.

Fortress World scenario

Outside the fortress, the majority is mired in poverty, denied access to scarce land resources and restricted in mobility, and basic rights such as freedom of association and expression.

Figure 4: Changes in total irrigated land area

Figure 4: Changes in total irrigated land area(Source: UNEP/GRID 2006; Projections are based on the scenario assumptions; data for 2005: SAO Stat 2005 and GEO data portal)

In the Fortress World scenario, a few powerful regional, sub-regional and international actors are able to rally together and secure control over land resources; they are sufficiently organized to protect their own interests and to create lasting alliances between them. Land based wealth, resources and conventional governance systems for most are eroding. The elite retreat into protected enclaves. Outside the fortress, the majority is mired in poverty, denied access to scarce land resources and restricted in mobility and basic rights such as freedom of association and expression. The authorities employ active means of repression to guarantee exclusive access to needed resources (such as oil fields and key mines) and to stop further degradation of the regional and sub-regional land resources. Strategic mineral reserves, freshwater and important biological resources are put under strict control. Technology is maintained in the fortresses, with some continued innovation, but deteriorates elsewhere. Pollution within the fortress is reduced through increased efficiency and recycling. Waste is exported outside the enclaves, contributing to the extreme environmental deterioration induced by the unsustainable practices of the desperately poor and by the extraction of resources for the wealthy. However, favored resort areas including nature and hunting reserves are declared ecological protection zones, from which poor people are excluded.

In this scenario, the major line of conflict is between rich and poor people, a new functional divide replacing the old North-South notion. Socioeconomic equity is very low, at the national and sub-regional levels, though it is higher within the fortress and outside. This social system is contingent on the organizational ability of the privileged enclaves to maintain control over the disenfranchised.

Land developments in the Fortress World scenario relating to human settlements, pastures and rangelands, agricultural land expansion, and land degradation paint a bleak future for the marginalized majority. The growing population of the underprivileged is not matched by an equivalent increase in requisite land resources. The “fortress dwellers” continue to have the biggest share of land resources for settlement and agricultural production. Expansion of settled areas places significant pressure on agricultural lands and valued ecosystems. Proliferation of poorly serviced and densely populated urban settlements is witnessed as other settled areas expand into agricultural, forest, rangeland or other land types with the shares varying from sub-region to sub-region.

Larger tracts of rangelands are reserved for grazing livestock. Grazing areas increase in all sub-regions. The increase is at the expense of cropland, forest and marginal lands and human settlements. Land degradation escalates subsequently. In some sub-regions agriculture expands onto marginal land, which requires considerable input and careful management. Poor people lack adequate input and resources to sustainably manage their land, which is predominantly located in damaged environments; in contrast the rich own prime land and have an unparalleled share of resources. Pollution is rife and unsustainable land-use practices lead to various forms of land degradation, including wind and soil erosion, soil compaction, waterlogging, salinization, and nutrient depletion. The state of land resources deteriorates between 2000 and 2015 and continues to worsen at a faster rate in the 2015-2025 period. A larger proportion of the population is forced to produce food on increasingly less productive land. The risk of water erosion increases as more land is brought under intensive agriculture and there is a high rate of conversion of natural and semi-natural areas into built-up areas for industrial activities, infrastructure and tourism. Land remaining under agriculture is more vulnerable to water erosion.

In countries and sub-regions where the majority of farmers are smallholders, the rate of degradation is higher owing to the poor quality of available land and inadequate financial and human resources. Highly degraded agricultural land remains under production due to the lack of availability of alternatives as most land, including protected areas, forests, wetlands and woodlands, has been expropriated and managed by those in the “fortresses” and the few prosperous people from the minority enclaves. Human vulnerability to environmental change increases. The lower yields of traditional staple food crops, such as maize in Eastern and Southern Africa and yams in Western Africa, indicate continued production in degraded lands.

The Great Transitions scenario

Sensitive governments emerge to both express and stimulate the process of sustainable land management balancing the three pillars of sustainable development: society, environment and economy.

In the Great Transitions scenario, regional, sub-regional, national and local society, rather than descending into cruelty and chaos, evolves to a higher stage as a new land-use paradigm emerges.

This transition requires structural rather than incremental changes in social practices and therefore a discontinuity with the current trajectory. Such transition may take two forms.

Figure 5: Sub-regional picture of degraded cropland by 2025 under the various scenarios

Figure 5: Sub-regional picture of degraded cropland by 2025 under the various scenarios(Source: UNEP, 2006)

First, Eco-communalism envisions a patchwork of semi-isolated and self-reliant communities of land users. In this world, there are high levels of equity (with regard to land ownership), low economic growth, and low population growth.

Second, the New Sustainability Paradigm is a constructive and popular basis for social and environmental reconstruction, and redressing tensions. In this paradigm sensitive governments emerge to both express and stimulate the process of sustainable land management, balancing the three pillars of sustainable development: society, environment and economy.

Science and technology form the backbone of land management. The values of simplicity, tranquility and community begin to displace those of consumerism, competition and individualism. Slowly, these processes coalesce into a region-wide approach, with many people searching for new ideals, meaning and forms of social existence based on the pursuit of intergenerational equity. Equity and sustainability, rather than economic growth, come to define land development. Agricultural and industrial technology transfer and joint sustainable development initiatives usher in a new era of cooperation between all socioeconomic segments of the region and sub-regions. All sub-regions pioneer land-use technologies and development approaches that conform to their unique climate, geography, resources, demographics and religious and cultural traditions. In the new economic arrangements, markets are used to steer agricultural production and product distribution efficiency, but within the limits of market as required by defined social, cultural and environmental goals.

A variety of policy mechanisms are used to achieve the sustainability programme. These include a revised tax system and other market signals to discourage poor land-use practices. The polluter pays principle is implemented in all sub-regions. Anti-social corporate behavior is discouraged by, among other methods, the public disclosure of information. Well-designed environmental, economic and social indicators measure the effectiveness of policies, giving the public an informed basis for seeking change. Devolved forms of governance evolve; land stewardship, and mechanisms for land-use decision making are established from local to regional scales. In this nested structure, Africa’s sub-regions, nations and communities have considerable control over socioeconomic decisions including approaches to agricultural production and environmental conservation.

Regional governance is based on a federation of regions, which, through a rejuvenated AU and a truly regional civil service, effectively fosters cooperation, security and quality of land. Population growth slows and then stabilizes at relatively low levels as poverty is eliminated and women become equal participants in the life of communities. Inherited environmental problems are abating, though some effects linger for many decades. Land-based conflicts are resolved by negotiation, collaboration and consensus. The exhilaration of pioneering a socially and environmentally superior way of life becomes a powerful attracting force for land users.

The main defining contours of the Great Transitions scenario are seen in positive indicators of human settlements, pastures and rangelands management, agricultural land expansions, the expansion of irrigated land, and the reduction in land degradation from water erosion, salinization and fertility loss. The socioeconomic and environmental impacts of these positive developments set in largely after 2015 and continue to be entrenched in land-use practices up to 2025. Economic growth ideals drive the demand for livestock and crop products higher but these are tempered by environmental concerns. Pressure on forests and other ecosystems, such as wetlands and rangelands, is reduced through careful land-use planning. Definite improvement in grazing land productivity can also be expected due to the adoption of sustainable livestock management practices and improvements in herd quality. Agricultural extension propels the transition to sustainable livestock practices.

Agricultural land expands by about 10 percent between 2005 and 2025, a larger increase than the 5 percent of the Policy Reform scenario. The increases in agricultural land are based on sustainable land-use principles, and land and water constraints at the sub-regional and country levels. In Southern and Eastern Africa, where agricultural land increases by about 20 percent, some of the increase is met by returning to production land held by the government. Much of the increase in agricultural production is made possible through increase in irrigated land. Expansion of irrigated land is encouraged by decreases in water prices. More secure access to water is ensured in most sub-regions as regional and sub-regional structures are developed to facilitate cross-border water resources management. The rate of land degradation slows between 2005 and 2015. Loss of agricultural land due to severe degradation drops to 0.1 million ha per year over the first half of the scenario, 10 percent of the rate assumed in the Policy Reform scenario. From 2015 to 2025, degraded agricultural land is greatly restored, leading to increased availability of land for agriculture, forests and other uses. More land is protected by local and national or sub-regional regulatory and governance mechanisms. Land degradation is greatly reduced through drainage, irrigation and land reclamation systems.

In this scenario, per capita consumption of agricultural products (meat, milk, grains) is lower, leading to a smaller area required for crop production and livestock grazing. This lowers the risk of water erosion, particularly after 2015. Efficient soil and water conservation systems are put in place to complement sustainable land management practices. Expansion of settlement areas is controlled and is less significant in conversion of natural and semi-natural systems. This is markedly different from the situation envisaged in the Market Forces scenario. The expansion of the built environment is contained as in the first half of the Policy Reform scenario, as concerns for protecting productive cropland, forests and other ecosystems lead to urban planning policies that favor more compact settlement patterns and limit the proliferation of poorly serviced slums.

Containment of negative land-cover changes and forest-cover loss are key sustainability goals. The rate of forest loss gradually decreases in the scenario to zero by 2015 and forest areas increase thereafter. Forest protection policies and land-use strategies that support more compact settlements, the contraction of grazing lands and land restoration support the maintenance of the integrity of agro-ecosystems. The sustainable use of forest products is encouraged.

Policy lessons from the scenarios

An analysis and synthesis of the overall regional and sub-regional conditions, policies and initiatives in land resources demonstrates the value of appropriate policy responses, which can maximize development opportunities while ensuring environmental quality. An understanding of the driving forces, indicators and policy options under each of the four scenarios is a prerequisite for positive action. Policy responses are needed to alleviate, mitigate or suppress driving forces that may worsen land degradation.

The scenarios explored in the land theme show succinctly that different policy options exist. The scenarios are tools for integrating scientific knowledge about the consequences of anthropogenic pressures and natural processes, and for elucidating potential environmental options. The range of available opportunities, although affected by the magnitude and nature of the driving forces, depends mainly on institutionalizing sustainable land management practices.

The objective of achieving food security for a rapidly growing population, while maintaining the productivity of agricultural land and forests and avoiding land degradation, presents numerous challenges. There is no simple recipe for achieving this. The scenario narrative presents a picture of how this might be accomplished under different development pathways. It reveals the multidimensional character of the problem, the variety of initiatives needed to address these problems, as well as the immense policy challenge. Concerted government action will be needed to build the required capacity for R & D activities and extension services, provide well-functioning markets and adequate infrastructure, counter the perverse subsidies in developed countries, and implement incentives for a shift toward more ecologically friendly agriculture, forestry, and land-use practices. The adequacy of water resources will play a critical role in achieving these goals. A substantial increase in irrigated land and availability of irrigation water will go a long way in helping achieve food security goals. This will require prudent management of the freshwater resources.

Improving the distribution of wealth, access to resources and economic opportunities are key factors to the success of regional, sub-regional and national land policies. The mitigation measures that would make land use environmentally sound revolve around improved conservation, and the effective use of marginal and low-potential agricultural lands. The measures to stem the increasing risk of water erosion must be revised in order to adapt to climate change, avoid the conversion to agriculture of other natural and semi-natural systems and address the consequences of agricultural intensification.

There is an urgent need to develop well coordinated country-specific and sub-region-specific land degradation monitoring programmes. These programmes would produce and share information needed for land-use decision making and policy development on degradation, and in particular for disaster preparedness, mitigation and management. The large differences in the estimated extent of land degradation under the different scenarios demand a policy-sensitive early warning system that is able to make quick and effective responses.

Further reading

- Conway, G., 1997. The Doubly Green Revolution: Food for All in the 21st Century. Penguin Books, London

- MI, 2002. Threshold 21 – Introduction. Millennium Institute.

- Raskin, P., Heaps, C., Sieber, J. and Kemp-Benedict, E., 1999. PoleStar System Manual for Version 2000. PoleStar Series Report No. 2. Stockholm Environment Institute, Boston.

- SARIPS, 2000. SADC Human Development Report: Challenges and Opportunities for Regional Integration. Southern African Research Institute for Policy Studies. Southern Africa Political Economy Series Books, Harare.

- Scherr, S.J. and Yadav, S., 1996. Land Degradation in the Developing World: Implications for Food, Agriculture, and the Environment to 2020. 2020 Discussion Paper No. 14. International Food Policy Research Institute,Washington, D.C.

- UNEP, 2006. Africa Environment Outlook 2.

|

|

| Disclaimer: This article is taken wholly from, or contains information that was originally published by, the United Nations Environment Programme. Topic editors and authors for the Encyclopedia of Earth may have edited its content or added new information. The use of information from the United Nations Environment Programme should not be construed as support for or endorsement by that organization for any new information added by EoE personnel, or for any editing of the original content. |