Pygmy sperm whale

The Pygmy sperm whale (scientific name: Kogia breviceps) is one of two species of cetaceans in the family Kogiidae, the other being the Dwarf sperm whale. As their names suggests they are small compared to their distant cousin the Sperm whale. Like Sperm whales, their mouth is on the underside of their body, but unlike Sperm whales their small teeth are few in number and are sharply pointed and curved. Like Sperm whales, they are suction feeders and chiefly consume squid. Knowledge about these species has been slow to accumulate, and in fact, the existence of the two species only became widely accepted in 1966.(Handley 1966)

The Pygmy sperm whale is a toothed whale and can be recognised as such by the single blowhole and the presence of teeth. It is an easily recognisable small whale with a stocky body reaching up to four meters in length. It has a large and distinctly square upper jaw which projects above the narrow lower jaw. The blowhole is positioned at the front of the head and directed forward obliquely. A small dorsal fin is present two-thirds down the body and the tail flukes are small. The flippers are almost spear-shaped. The body is blue-black to charcoal grey in colour, while the underside is white and the inside of the mouth and the lips are white. There is often a crescent-shaped, light mark between the eye and the flipper. Pygmy sperm whales are usually found either alone, or in small groups of up to five individuals. The blow is unique amongst whales by being obliquely forward directed.

Pygmy sperm whales are usually seen in small groups of six or fewer individuals, but there are few documented sightings. They tend to stay in deep water, beyond the continental shelf, and not much is known about their behavior. Calves are about 1.2 meters (m) long at birth (an adult's total length ranges from 2.7 to 3.4 m); gestation lasts nine to eleven months; and the calf nurses for about a year. Although strandings are relatively frequent in the southeastern United States, sometimes because the whales have swallowed plastic bags, these animals are sighted so infrequently that they are considered uncommon for conservation purposes. Pygmy sperm whales are believed to feed mostly on cephalopods, and may mistake floating plastic bags for squid.

Contents

Physical Description

The Pygmy sperm whale is a small whale averaging about three meters in length for both sexes. Calves are about 55 kilograms at birth. They have a swollen nose and head, which takes up about 15% of their body length. Their head is conical with a small underslung jaw that opens beneath the upper jaw in a shark-like manner. The flippers are short, broad, and far forward on the body. They have a small curved dorsal fin.

The Pygmy sperm whale is a steely grey color with a distinct pink tinge. In the water they often look purple. They are a paler grey on the belly. Between the eye and the flipper is a small white/pale grey bracket mark. This is often called a "false gill", further attributing to its resemblance to a shark. There is another similar pale spot in front of the eye. Scarring is rare. They have a short rostrum which makes their wide skull triangular.

Pygmy sperm whales have 12 to 16 teeth on each side and their blowhole is slightly displaced to the left. These two traits distinguish thePygmy sperm whale, Kogia breviceps, from the Dwarf sperm whale, K. simus (Minasian et al. 1984, Watson 1981).

The tail flukes will often appear before a deep dive. Dive duration time is not clearly known (Kinze, 2002). It is often confused with the Dwarf sperm whale, Kogia sima, but the dwarf sperm whale does not occur in British and Irish waters (Jefferson et al., 1994). Length Range of the species is 2.7 to 3.4 meters, and body mass typically varies from 318 to 408 kilograms.

Behavior

Though there are sightings of solitary individuals, most of the whales travel in small pods of three to six individuals Like the great Sperm whale, Physeter macrocephalus, the pygmy sperm whale breaches, landing in the water tail first. Also like the great sperm whale, pygmy sperm whales have spermaceti in their foreheads. This suggests that they have the ability to dive into very deep water and hover motionless at any depth to wait for prey. They have great speed and can stay under water for long periods of time, another reason to suspect very deep dives.

The Pygmy sperm whale is often found stranded. There seems to be a relation between strandings and motherhood, as most strandings are mothers with newborn calves. Kogia breviceps have been descibed as being very slow and deliberate swimmers while breathing and swimming near the surface.

Reproduction

Key reproductive features are: Iteroparous; Seasonal breeding; Gonochoric/gonochoristic/dioecious (sexes separate); Sexual; Viviparous. Mating usually takes place in the summer. Gestation lasts for about nine to eleven months and the calf is born in the spring.The calf remains with its mother and is nursed for about 12 months. Calves are about 1.2 meters long and about 55 kilograms at birth.

Lifespan/Longevity

These mammals are known to be able to live at least 17 years in the wild (David Macdonald 1985)

Distribution and Movements

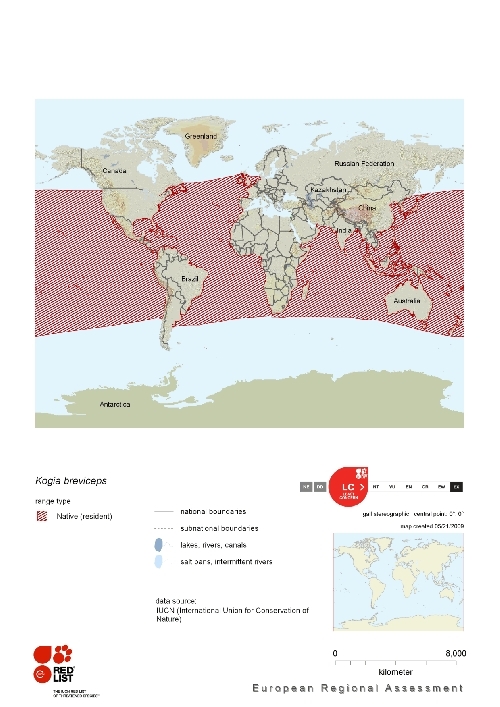

The IUCNRed List reports that "Pygmy sperm whales are known from deep waters (outer continental shelf and beyond) in tropical to warm temperate zones of all oceans (McAlpine 2002). This species appears to prefer somewhat more temperate waters than does the dwarf sperm whale. The range of Kogia breviceps is poorly known, though a lack of records of live animals may be more due to inconspicuous behaviour rather than rarity. Most information stems from strandings (especially females with calves), which may give an inaccurate picture of the actual distribution at sea (Culik 2004)."

Habitat

The Pygmy sperm whale prefers warm tropical waters. They may migrate to more temperate waters in the summer months. They also stay in deep waters (Watson 1981).

The IUCNRed List adds:

Kogia breviceps is rarely seen at sea; it tends to live a long distance from shore and has inconspicuous habits. According to Caldwell and Caldwell (1989) K. breviceps lives in oceanic waters beyond the edge of the continental shelf while K. sima lives over or near the edge of the shelf. However, this separation was not apparent in the study by Mullin et al. (1994) who, by aerial observation, found both species over water depths of 400-600 m in the north-central Gulf of Mexico. These waters of the upper continental slope were also characterized by high zooplankton biomass (Baumgartner et al. 2001).

Studies of feeding habits, based on stomach contents of stranded animals, suggest that this species feeds in deep water, primarily on cephalopods and, less often, on deep-sea fishes and shrimps (dos Santos and Haimovici 2001; McAlpine et al. 1997). In South Africa, they take at least 67 different prey species and appear to feed in deeper waters than do dwarf sperm whales (Ross 1979).

Feeding Habits

Pygmy sperm whales eat mostly squid, shrimp, fish, and crabs with what seems to be a preference for deepwater foraging. (Watson 1981)

Economic Importance for Humans

There is little economic benefit with respect to harvesting of this species; however, the scientific and research benefits from preserving this species are very high. The species is relatively uncommon so few are taken by the Japanese, and only an occasinal individual is taken by Indonesians.

Threats and Conservation Status

Less is known about this species in comparison with many other cetaceans. The infrequency of sightings is often assumed as rareness. It is vulnerable to Hawaiian fisheries and gillnets, float lines and long lines.

The IUCNRed List reports that "there is considerable uncertainty about the status of this species, which may span a range from Least Concern to a Threatened category. There is no information on abundance or on trends in global abundance.

There are no estimates of global abundance. Abundance of this and similar whales is often underestimated using visual survey methods because they dive for long periods and are inconspicuous when they surface (Barlow 1999). The frequency with which they strand in some areas (such as Florida and South Africa) suggests that they may not always be as uncommon as sightings would suggest. Recent genetic studies suggest the there is some gene flow between the Atlantic and Indo-Pacific oceans (S. J. Chivers pers. comm.).

Delineations between stocks are often difficult to determine, therefore assessments should be considered ongoing processes. In the case of the Pygmy sperm whale, concern that sightings may be confused with the cogener K. sima (the Dwarf sperm whale) further complicates the estimation of abundance. There are estimated to be about 247 (CV = 106%) off California, Oregon, and Washington (Barlow 2003); 7,251 (CV=77%) off Hawaii (Barlow 2006); 742 of both species of Kogia (CV=29%) in the northern Gulf of Mexico (Mullin et al. 2004); and 395 of both species (CV=40/75%) in the western North Atlantic (Waring et al. 2006).

And:

Although they have never been taken in large numbers and have never been hunted commercially, small numbers of the species have been taken in coastal whaling operations off Japan, Indonesia, Taiwan, the Lesser Antilles, and Sri Lanka (Jefferson et al. 1993).

A few have been killed in gillnet fisheries of Sri Lanka, Taiwan and California, and it is likely they are killed in gillnets elsewhere as well (Jefferson et al. 1993; Barlow et al. 1997). Perez et al. (2001) reported on occasional bycatch in fisheries in the northeast Atlantic (mostly gillnet and purse seine operations). However, although it is taken in small numbers both directly and incidentally in fisheries, Baird et al. (1996) found no serious threats to its status.

A young male Pygmy sperm whale stranded alive on Galveston Island, Texas, USA and died in a holding tank 11 days later. During necropsy, the first two stomach compartments (forestomach and fundic chamber) were found to be completely occluded by various plastic bags (Laist et al. 1999). Such ingestion of plastics, with associated gut-blockage, appears to be a common issue in this species.

This species, like beaked whales, is likely to be vulnerable to loud anthropogenic sounds, such as those generated by navy sonar and seismic exploration (Cox et al. 2006).

In 2005, a large series of unusual stranding events over about 3 weeks in and around Taiwan included several Kogia (Wang and Yang 2006; Yang et al. 2008) with at least two pygmy sperm whales (Yang et al. 2008). It is unknown if military, seismic or other loud noise-producing human activities resulted in these strandings.

There are high levels of unexplained strandings in the Gulf of Mexico and the Atlantic coast of Florida (Waring et al. 2006).

Possible impacts of climate change on the marine environment may affect Pygmy sperm whales, although the nature of impacts has not been demonstrated (Learmonth et al. 2006).

References

- Museum of Texas Tech University, Pygmy Sperm Whale, accessed April 5, 2011

- Aguiar-Dos Santos, R. and Haimovici, M. 2001. Cephalopods in the diet of marine mammals stranded or incidentally caught along southeastern and southern Brazil (21- 34º S). Fisheries Research 52: 99-112.

- Baird, R. W., Nelson, D., Lien, J. and Nagorsen, D. W. 1996. Status of the pygmy sperm whale, Kogia breviceps, in Canada. Canadian Field-Naturalist 110: 525-532.

- Balcomb, K. C. and Claridge, D. E. 2001. A mass stranding of cetaceans caused by naval sonar in the Bahamas. Bahamas Journal of Science 8(2): 2-12.

- Banks, R. C., R. W. McDiarmid, A. L. Gardner, and W. C. Starnes. 2003. Checklist of Vertebrates of the United States, the U.S. Territories, and Canada

- Banks, R. C., R. W. McDiarmid, and A. L. Gardner. 1987. Checklist of Vertebrates of the United States, the U.S. Territories, and Canada. Resource Publication, no. 166. 79

- Barlow, J. 1999. Trackline detection probability for long-diving whales. In: G. W. Garner, S. C. Amstrup, J. L. Laake, B. J. F. Manley, L. L. McDonald and D. G. Robertson (eds), Marine mammal survey and assessment methods, pp. 209-221. Balkema Press, Netherlands.

- Barlow, J. 2003. Preliminary estimates of the abundance of cetaceans along the U.S. west coast: 1991-2001. Southwest Fisheries Center Administrative Report LJ-03-03: 31 pp.

- Barlow, J. 2006. Cetacean abundance in Hawaiian waters estimated from a summer/fall survey in 2002. Marine Mammal Science 22(2): 446-464.

- Barlow, J., Forney, K. A., Hill, K. A., Brownell Jr., R. L., Caretta, R. L., Demaster, D. P., Julian, D. P., Lowry, M. S., Ragen, M. S. and Reeves, R. R. 1997. U.S. Pacific marine mammal stock assessments: 1996. NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-SWFSC 248: 223 pp.

- Baumgartner, M. F., Mullin, K. D., May, L. N. and Leming, T. D. 2001. Cetacean habitats in the northern Gulf of Mexico. Fishery Bulletin 99: 219-239.

- Blainville 1838. Ann. Franc. Etr. Anat. Phys., 2:337.

- Bloodworth, Brian E., and Daniel K. Odell. 2008. Kogia breviceps (Cetacea: Kogiidae). Mammalian Species, no. 819. 1-12

- Borges, P.A.V., Costa, A., Cunha, R., Gabriel, R., Gonçalves, V., Martins, A.F., Melo, I., Parente, M., Raposeiro, P., Rodrigues, P., Santos, R.S., Silva, L., Vieira, P. & Vieira, V. (Eds.) (2010). A list of the terrestrial and marine biota from the Azores. Princípia, Oeiras, 432 pp.

- Bruyns, W.F.J.M., (1971). Field guide of whales and dolphins. Amsterdam: Publishing Company Tors.

- Caldwell, D. K. and Caldwell, M. C. 1989. Pygmy sperm whale Kogia breviceps (de Blainville, 1838): Dwarf sperm whale Kogia simus Owen, 1866. In: S. H. Ridgway and R. Harrison (eds), Handbook of marine mammals, Vol. 4: River dolphins and the larger toothed whales, pp. 234-260. Academic Press.

- Carretta, J. V., Forney, K. A., Muto, M. M., Barlow, J., Baker, J., Hanson, J. and Lowry, M. S. 2006. U.S. Pacific marine mammal stock assessments: 2005. NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-SWFSC.

- Chivers, S. J., Leduc, A. E., Robertson, K. M., Barros, N. B. and Dizon, A. E. 2005. Genetic variation in Kogia spp., with preliminary evidence for two species of Kogia sima. Marine Mammal Science 21(4): 619-634.

- Culik, B. M. 2004. Review of small cetaceans: Distribution, behaviour, migration and threats. Marine Mammal Action Plan/Regional Seas Reports and Studies 177: 343 pp.

- Felder, D.L. and D.K. Camp (eds.), Gulf of Mexico–Origins, Waters, and Biota. Biodiversity. Texas A&M Press, College Station, Texas.

- Fernández, A., Edwards, J. F., Rodriguez, F., Espinosa, A., De Los Monteros, Herraez, P., Castro, P., Jaber, J. R., Martin, V. and Arebelo, M. 2005. "Gas and fat embolic syndrome" involving a mass stranding of beaked whales (family Ziphiidae) exposed to anthropogenic sonar signals. Veterinary Pathology 42: 446-457.

- Frantzis, A. 1998. Does acoustic testing strand whales? Nature 392(5): 29.

- Gordon, D. (Ed.) (2009). New Zealand Inventory of Biodiversity. Volume One: Kingdom Animalia. 584 pp

- Handley, C. O. 1966. A synopsis of the genus Kogia (pygmy sperm whales). In: K. S. Norris (ed.), Whales, dolphins, and porpoises, pp. 62-69. University of California Press, Berkeley, California, USA.

- Hohn, A. A., Rotstein, D. S., Harms, C. A. and Southall, B. L. 2006. Multispecies mass stranding of pilot whales (Globicephala macrorhynchus), minke whale (Balaenoptera acutorostrata), and dwarf sperm whales (Kogia sima) in North Carolina on 15-16 January 2005. NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS SEFSC 537: 222.

- Howson, C.M. & Picton, B.E. (ed.), (1997). The species directory of the marine fauna and flora of the British Isles and surrounding seas. Belfast: Ulster Museum. Museum publication, no. 276.

- IUCN (2008) Cetacean update of the 2008 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.

- Jefferson, T.A., Leatherwood, S. & Webber, M.A., (1994). FAO species identification guide. Marine mammals of the world. Rome: United Nations Environment Programme, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

- Jepson, P. D., Arebelo, M., Deaville, R., Patterson, I. A. P., Castro, P., Baker, J. R., Degollada, E., Ross, H. M., Herraez, P., Pocknell, A. M., Rodriguez, F., Howie, F. E., Espinosa, A., Reid, R. J., Jaber, J. R., Martin, V., Cunningham, A. A. and Fernandez, A. 2003. Gas-bubble lesions in stranded cetaceans. Nature 425: 575-576.

- Kinze, C. C., (2002). Photographic Guide to the Marine Mammals of the North Atlantic. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Laist, D. W., Coe, J. M. and O'Hara, K. J. 1999. Marine debris pollution. In: J. R. Twiss and R. R. Reeves (eds), Conservation and Management of Marine Mammals.

- Learmonth, J. A., Macleod, C. D., Santos, M. B., Pierce, G. J., Crick, H. Q. P. and Robinson, R. A. 2006. Potential effects of climate change on marine mammals. Oceanography and Marine Biology: An Annual Review 44: 431-464.

- David Macdonald (1985) The Encyclopedia of Mammals. Facts on File: New York.

- Mcalpine, D. F. 2002. Pygmy and dwarf sperm whales Kogia breviceps and K. simus. In: W. F. Perrin, B. Wursig and J. G. M. Thewissen (eds), Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals, pp. 1007-1009. Academic Press.

- Mcalpine, D. F., Murison, L. D. and Hoberg, E. P. 1997. New records for the pygmy sperm whale, Kogia breviceps (Physeteridae) from Atlantic Canada with notes on diet and parasites. Marine Mammal Science 13(4): 701-704.

- MEDIN (2011). UK checklist of marine species derived from the applications Marine Recorder and UNICORN, version 1.0.

- Mead, James G., and Robert L. Brownell, Jr. / Wilson, Don E., and DeeAnn M. Reeder, eds. 2005. Order Cetacea. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference, 3rd ed., vol. 1. 723-743

- Minasian, S., K. Balcomb, III, L. Foster. 1984. The World's Whales. U.S.: The Smithsonian Institution.

- Mullin, K. D. and Fulling, G. L. 2004. Abundance of cetaceans in the oceanic northern Gulf of Mexico, 1996-2001. Marine Mammal Science 20(4): 787-807.

- Mullin, K. D., Hoggard, Q. and Hansen, L. J. 2004. Abundance and seasonal occurrence of cetaceans in outer continental shelf and slope waters of the north-central and northwestern Gulf of Mexico. Gulf of Mexico Science 22: 62-73.

- Mullin, K., Hoggard, W., Roden, C., Lohoefener, R., Rogers, C. and Taggart, B. 1991. Cetaceans on the upper continental slope in the northcentral Gulf of Mexico. OCS Study MMS 91-0027: 108 pp.

- Perez, C., Lopez, A., Sequeira, M., Silva, M., Herrera, R., Goncalves, J., Valdes, P., Mons, L., Freitag, L., Lens, S. and Cendero, O. 2001. Stranding and by-catch of cetaceans in the northeastern Atlantic during 1996.: 4 pp.. Copenhagen, Denmark.

- North-West Atlantic Ocean species (NWARMS)

- Perrin, W. (2011). Kogia breviceps (de Blainville, 1838). In: Perrin, W.F. World Cetacea Database. Accessed through: Perrin, W.F. World Cetacea Database at http://www.marinespecies.org/cetacea/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=137113 on 2011-03-18

- Ramos, M. (ed.). 2010. IBERFAUNA. The Iberian Fauna Databank

- Reid. J.B., Evans. P.G.H., Northridge. S.P. (ed.), (2003). Atlas of Cetacean Distribution in North-west European Waters. Peterborough: Joint Nature Conservation Committee.

- Rice, Dale W. 1998. Marine Mammals of the World: Systematics and Distribution. Special Publications of the Society for Marine Mammals, no. 4. ix + 231

- Ross, G. J. B. 1979. Records of pygmy and dwarf sperm whales, genus Kogia, from southern Africa, with biological notes and some comparisons. Annals of the Cape Provincial Museums (Natural History) 11(14): 259-327.

- Simmonds, M. P. and Lopez-Jurado, L. F. 1991. Whales and the military. Nature 351: 448.

- Southall, B. L., Braun, R., Gulland, F. M. D., Heard, A. D., Baird, R. W., Wilkin, S. and Rowles, T. K. 2006. Hawaiian melon-headed whale (Peponocephala electra) mass stranding event of July 3-4, 2004. NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-OPR 31: 73 pp.

- Southwest fFsheries Science Center, Dwarf and Pygmy Sperm Whale, NOAA

- UNESCO-IOC Register of Marine Organisms

- Watson, L. 1981. Sea Guide to Whales of the World. London: Hutchinson and Co..

- Taylor, B. L., Chivers, S. J., Larese, J. and Perrin, W. F. 2007. Generation length and percent mature estimates for IUCN assessments of Cetaceans. Southwest Fisheries Science Center.

- Wang, J. Y. and Yang, S. C. 2006. Unusual cetacean stranding events of Taiwan in 2004 and 2005. Journal of Cetacean Research and Management 8: 283-292.

- Waring, G. T., Josephson, E., Fairfield, C. P. and Maze-Foley, K. (eds). 2006. U.S. Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico marine mammal stock assessments - 2005. NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-NE, pp. 346 pp..

- Wilson, Don E., and DeeAnn M. Reeder, eds. 1993. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference, 2nd ed., 3rd printing. xviii + 1207

- Wilson, Don E., and F. Russell Cole. 2000. Common Names of Mammals of the World. xiv + 204

- Wilson, Don E., and Sue Ruff, eds. 1999. The Smithsonian Book of North American Mammals. xxv + 750

- van der Land, J. (2001). Tetrapoda, in: Costello, M.J. et al. (Ed.) (2001). European register of marine species: a check-list of the marine species in Europe and a bibliography of guides to their identification. Collection Patrimoines Naturels, 50: pp. 375-376

- Yang, W.-C., Chou, L.-S., Jepson, P. D., Brownell Jr., R. L., Cowan, D., Chang, P.-H., Chiou, H.-I., Yao, C.-J., Yamada, T. K., Chiu, J.-T., Wang, P.-J. and Fernandez, A. 2008. Unusual cetacean mortality events in Taiwan, possibly linked to naval activities. Veterinary Record 162: 184-186.