Plunkett, Roy J.

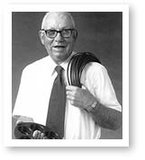

Roy J. Plunkett with a cable insulated with Teflon and a Teflon-coated muffin tin. (Source: Gift of Roy Plunkett, Courtesy Hagley Museum and Library)

Roy J. Plunkett with a cable insulated with Teflon and a Teflon-coated muffin tin. (Source: Gift of Roy Plunkett, Courtesy Hagley Museum and Library) From the 1930s to the present, beginning with neoprene and nylon, the American chemical industry has introduced a cornucopia of polymers to the consumer. Teflon, discovered by Roy Plunkett (1910–1994) at DuPont's Jackson Laboratory in 1938, was an accidental invention—unlike most of the other polymer products. But as Plunkett often told student audiences, his mind was prepared by education and training to recognize novelty.

As a poor Ohio farm boy during the Depression, Plunkett attended Manchester College, operated by the Church of the Brethren. His roommate for a time at this small college was Paul Flory, who would win the 1984 Nobel Prize in chemistry for his contributions to the theory of polymers. Like Flory, Plunkett went on to Ohio State University for a doctorate, and also like Flory he was hired by DuPont. Unlike Flory, Plunkett made his entire career at DuPont.

Plunkett's first assignment at DuPont was researching new chlorofluorocarbon refrigerants—then seen as great advances over earlier refrigerants like sulfur dioxide and ammonia, which regularly poisoned food-industry workers and people in their homes. Plunkett had produced 100 pounds of tetrafluoroethylene gas (TFE) and stored it in small cylinders at dry-ice temperatures preparatory to chlorinating it. When he and his helper prepared a cylinder for use, none of the gas came out—yet the cylinder weighed the same as before. They opened it and found a white powder, which Plunkett had the presence of mind to characterize for properties other than refrigeration potential. He found the substance to be heat resistant and chemically inert, and to have very low surface friction so that most other substances would not adhere to it. Plunkett realized that against the predictions of polymer science of the day, TFE had polymerized to produce this substance—later named Teflon—with such potentially useful characteristics. Chemists and engineers in the Central Research Department who had special experience in polymer research and development investigated the substance further. Meanwhile, Plunkett was transferred to the tetraethyl lead division of DuPont, which produced the additive that for many years boosted gasoline octane levels.

At first it seemed that Teflon was so expensive to produce that it would never find a market. Its first use was fulfilling the requirements of the gaseous diffusion process of the Manhattan Project for materials that could resist corrosion by fluorine or its compounds (see Ralph Landau). Teflon pots and pans were invented years later. The awarding of Philadelphia's Scott Medal in 1960 to Plunkett—the first of many honors for his discovery—provided the occasion for the introduction of Teflon bakeware to the public: each guest at the banquet went home with a Teflon-coated muffin tin.

Further Reading