Orange River

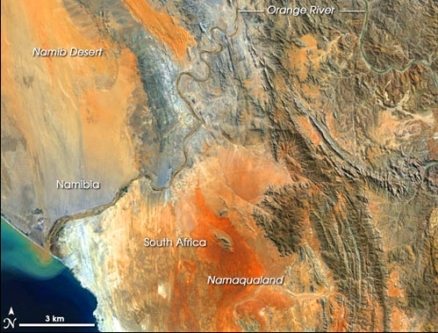

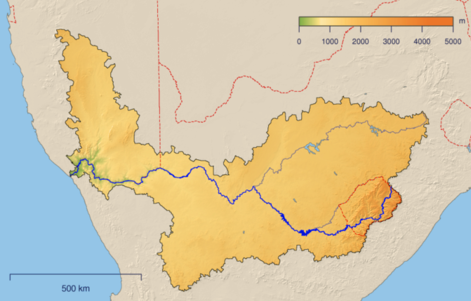

The Orange River is the longest watercourse in Southern Africa. Lying south of the Zambezi River, The Orange River rises in the Drakensberg Mountains and flows westward to discharge into the Atlantic Ocean. The river has a length of 2208 kilometres and drains 48 percent of the land area of South Africa and forms the national boundary between that country and Namibia. The total drainage area amounts to 896,368 square kilometres, and the discharge at the mouth is about 11.5 cubic kilometres per annum.

Excessive nutrient loading from overly intensive fertilizer usage in agricultural areas in the Vaal and middle reach Orange River is the major water quality issue in the basin. Headwaters areas of the basin support high endemism in flora and reptiles, while the middle reaches of the basin boast significant endemism in small mammals. Lower reaches of the basin support high endemism in both reptiles and small mammals.

Contents

Climate

The meteorology varies dramatically thorughout the catchment basin, with rainfall achieving values in excess of 2000 millimetres per annum in the headwaters to a scant 40 millimetres at the river mouth. The generally hot climate in austral summer exacerbates the frequency of algae blooms in the middle reaches of the Orange basin, which blooms arise from excessive fertilizer runoff from the agricultural uses in this part of the basin.

River course

The Orange River basin dominates drainage in southern Africa. Public Domain The Orange River headwaters rise near the border of Lesotho and South Africa, in the South African Province of KwaZulu-Natal, just below the western ridgeline of the Drakensberg Range. For a short run, the Orange River flows within Lesotho, where it is known as the Senqu. The upper reaches of the Orange River can be construed to the the river segment that flows through the Drakensberg alti-montane grassland and woodland ecoregion and the highveld grassland.

The Orange River basin dominates drainage in southern Africa. Public Domain The Orange River headwaters rise near the border of Lesotho and South Africa, in the South African Province of KwaZulu-Natal, just below the western ridgeline of the Drakensberg Range. For a short run, the Orange River flows within Lesotho, where it is known as the Senqu. The upper reaches of the Orange River can be construed to the the river segment that flows through the Drakensberg alti-montane grassland and woodland ecoregion and the highveld grassland.

The Orange River flows westward after confluence with its chief tributary, the Vaal River. This middle reach drains most of the Nama Karoo ecoregion and a portion of the Kalahari xeric scrublands ecoregion. However, some deem the heart of the Kalahari as intrinsically endorheic and not capable of yielding significant influx to the Orange Basin. Some cartographers consider the Orange Basin to extend to the Nabbor and Molopo Basins; however, the Nabbob is [arheic] (e.g. merely a dry riverbed, whose rare flow merely disappears into the vast arid Kalahari Desert). Moreover, the Molopo has not produced discharge to the Orange in over a century, and most hydrologists consider functionally arheic.

Many of the tributaries to the Orange River in the middle reach travel through the Nama Karoo. The Nama Karoo and Kalahari xeric savanna ecoregions both exhibit a number of pan systems, the largest of which in the Orange Basin, the Grootvloer-Verneukpan complex in the Nama Karoo, plays an important role during fish migrations, enabling certain species to gain access to their breeding grounds in the upper reaches of the Sak River. When austral summer rainfall is high, the system also provides a link between the Orange and Sak river systems, which may enable an interchange of indigenous fish and other aquatic organisms.

Water quality

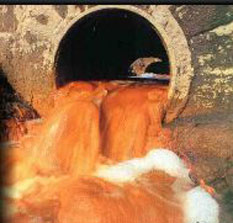

Untreated effluent entering the Orange River. Source: ORASECOM Beginning in the twentieth century, and driven by inexorable human population expansion in the basin, water quality in the Orange River has been relentlessly degraded. Chief proximate drivers of this water pollution are the addition of pesticides, herbicides and excessive fertilizer runoff (e.g. phosphates and nitrates) from basin agricultural uses. The nutrient loads contribute to Eutropication in the mainstem and adversely impact the ability of water treatment plants to produce appropriately treated water for domestic use, since these treatment plants were not designed to accomodate such degraded input.

Untreated effluent entering the Orange River. Source: ORASECOM Beginning in the twentieth century, and driven by inexorable human population expansion in the basin, water quality in the Orange River has been relentlessly degraded. Chief proximate drivers of this water pollution are the addition of pesticides, herbicides and excessive fertilizer runoff (e.g. phosphates and nitrates) from basin agricultural uses. The nutrient loads contribute to Eutropication in the mainstem and adversely impact the ability of water treatment plants to produce appropriately treated water for domestic use, since these treatment plants were not designed to accomodate such degraded input.

The chief [[water quality] concerns] are within South Africa, and more specifically in the densely populated areas of Johannesburg, Pretoria and the Vaal Triangle. Exacerbating the issue are insufficiency and ageing of the wastewater treatment plants of that locale, and the fact that discharges from that high population density region is at a higher elevation than the principal dams along the Orange River; thus, inevitably polluted discharges from the densely populated area reaches these warm termperature reservoirs, which are then poised to generate elevated bacterial levels.

Industrial sources of water pollution in the Vaal basin and Johannesburg region include: coal fired power plants, gold mining, petrochemical plants and pulp mills. Cumulatively, with municipal effluent, these sources contribute to total dissolved solids problems, water colour and water odour issues.

Diamond mining

Eureka diamond in cut form. Source: Fair Use Public Domain Arguably the world's richest diamond resources derive from the Orange River basin. The first diamond ever found in South Africa, the Eureka Diamond, was near Hopetown along the Orange River in the year 1867. A larger diamond, the Star of South Africa, was discovered in the same locale in 1869, generating a fervor of miners arriving to seek their fortunes. This diamond rush was followed by a diamond rush to extract diamonds directly from kimberlite at the town of Kimberley two years later, while alluvial diamonds continued to be extracted in the lower Orange. Presently, several commercial diamond mines operate on the lower reach of the Orange, but additional diamonds are extracted from the sandy intertidal zones, where the gems have been discharged to the Atlantic and washed back ashore.

Eureka diamond in cut form. Source: Fair Use Public Domain Arguably the world's richest diamond resources derive from the Orange River basin. The first diamond ever found in South Africa, the Eureka Diamond, was near Hopetown along the Orange River in the year 1867. A larger diamond, the Star of South Africa, was discovered in the same locale in 1869, generating a fervor of miners arriving to seek their fortunes. This diamond rush was followed by a diamond rush to extract diamonds directly from kimberlite at the town of Kimberley two years later, while alluvial diamonds continued to be extracted in the lower Orange. Presently, several commercial diamond mines operate on the lower reach of the Orange, but additional diamonds are extracted from the sandy intertidal zones, where the gems have been discharged to the Atlantic and washed back ashore.

Aquatic biology

Within the Orange River system 21 different fish taxa have been recorded, most of which are benthopelagic. The three largest benthopelagic native species are: the 170 centimetre (cm) long North African Catfish (Clarias gariepinus), the 122 cm Flathead Grey Mullet (Mugil cephalus) and the endemic 92 cm Vaal-Orange Largemouth Yellowfish (Labeobarbus kimberleyensis). Other noteworthy native benthopelagics are the basin endemic 56 cm Orange River Mudfish (Labeo capensis), the 56 cm basin endemic Smallmouth Yellowfish (Labeobarbus aeneus), the 45 cm Redbreast Tilapia (Tilapia rendalli). L aeneus may be useful in algae control in the Orange basin, since this omnivorous bottom feeder consumes considerable algae in its diet.  Leerfish ventures into the Orange River mouth. Source: Dennis Polack/FishWise/EOL The 146 cm Wild Common Carp (Cyprinus carpio carpio) is the largest introduced benthopelagic alien species in the Orange River.

Leerfish ventures into the Orange River mouth. Source: Dennis Polack/FishWise/EOL The 146 cm Wild Common Carp (Cyprinus carpio carpio) is the largest introduced benthopelagic alien species in the Orange River.

The largest fish species in the Orange River system is the 200 cm pelagic-neritic Leerfish (Lichia amia), which is a true aquatic apex predator, functioning at trophic level 4,5. Native demersal fish are the 40 cm South African Mullet (Liza richardsonii) and the near endemic 37 cm Rock Catfish (Austroglanis sclateri).

Basin vegetation

Upper reach flora

Aloe polyphylla spiral leaves. Source: Public Domain Some of Africa’s oldest centres of plant endemism occur in the Drakensberg Range. While the number of plant species solely restricted to the high Drakensberg is not well documented, within the KwaZulu-Natal region of the Drakensberg, 1750 vascular plant species have been recorded. Of these, 394 species are endemic to the southern Drakensberg. The peak levels of endemism occur in the highest elevations of the Orange River watershed. For example, Helichrysum palustre has been observed only from the summit plateau of the Drakensberg and the higher mountains on the Lesotho side between 2300 and 3400 metres (m) above mean sea level. The spiral aloe (Aloe polyphylla), a remarkable endemic plant of Lesotho, occurring only above 2000 m.

Aloe polyphylla spiral leaves. Source: Public Domain Some of Africa’s oldest centres of plant endemism occur in the Drakensberg Range. While the number of plant species solely restricted to the high Drakensberg is not well documented, within the KwaZulu-Natal region of the Drakensberg, 1750 vascular plant species have been recorded. Of these, 394 species are endemic to the southern Drakensberg. The peak levels of endemism occur in the highest elevations of the Orange River watershed. For example, Helichrysum palustre has been observed only from the summit plateau of the Drakensberg and the higher mountains on the Lesotho side between 2300 and 3400 metres (m) above mean sea level. The spiral aloe (Aloe polyphylla), a remarkable endemic plant of Lesotho, occurring only above 2000 m.

In the second half of the upper reaches there is a Highveld Grassland ecoregion, where dominant vegetation consists of grasses, admixed with geophytes and herbs. Dominant grass taxa are Thatching Grass (Hyparrhenia hirta) and Catstail Dropseed (Sporobolus pyramidalis). Larger flora are False Paperbark Thorn (Acacia sieberiana), Rhus rehmanniana, Selago densiflora, Spermacoce natalensis, Kohautia cynanchica, and Phyllanthus glaucophyllus.

Middle reach flora

In the Nama Karoo middle reach of the Orange Basin, dwarf shrubs (chaemaphytes) and grasses (hemicryptophytes) dominate the vegetative landscape, their relative abundances being dictated mainly by the modest rainfall and limestone soil. As a general trend, shrubs increase and grasses decrease with increasing aridity within this reach. Overgrazing by domestic livestock may obscure this pattern by suppressing the grass densities. Some of the more abundant shrubs include taxa within the following genera: Drosanthemum, Eriocephalus, Galenia, Pentzia, Pteronia, and Ruschia; moreover, the chief perennial grasses here are of the genera Aristida, Digitaria, Enneapogon, and Stipagrostis. Trees and large woody shrubs are generally restricted to watercourses, including Acacia karroo, Diospyros lycioides, Grewia robusta, Searsia lancea and Tamarix usneoides.

Lower reach flora

Dollar Plant, Namibia. Source: James Anderson The Orange River lower reach runs through the southern Namib Desert, an expansive region of large, shifting dunes. This area is botanically under-unexplored, and is deemed to be depauperate with regard to vegetation. The few species known to sparsely vegetate the dunes are the perennial grasses: Namib Dune Bushman Grass (Stipagrostis sabulicola) and Rough-leaved Bushman Grass (S. gonatostachys) as well as Monsonia ignorata and the Dune Succulent (Trianthema hereroensis). These perennial plants are found interspersed on the lower slopes of the dunes and have adapted to the incessantly shifting sands. Hummocks are formed between these sand dunes and the coastal zone. These hummocks are formed by the Nara plant (Acanthosicyos horridus), the Pencil Bush (Arthraerua leubnitziae) and the Dollar Plant (Zygophyllum stapfii).

Dollar Plant, Namibia. Source: James Anderson The Orange River lower reach runs through the southern Namib Desert, an expansive region of large, shifting dunes. This area is botanically under-unexplored, and is deemed to be depauperate with regard to vegetation. The few species known to sparsely vegetate the dunes are the perennial grasses: Namib Dune Bushman Grass (Stipagrostis sabulicola) and Rough-leaved Bushman Grass (S. gonatostachys) as well as Monsonia ignorata and the Dune Succulent (Trianthema hereroensis). These perennial plants are found interspersed on the lower slopes of the dunes and have adapted to the incessantly shifting sands. Hummocks are formed between these sand dunes and the coastal zone. These hummocks are formed by the Nara plant (Acanthosicyos horridus), the Pencil Bush (Arthraerua leubnitziae) and the Dollar Plant (Zygophyllum stapfii).

Basin terrestrial fauna

Upper reach fauna

Mountain Reedbuck, Drakensberg Range. Source: Thurner Hof The uppermost reaches of the Orange River develop within the The Drakensberg alti-montane grasslands and woodlands ecoregion which extends along the Drakensberg Mountain Range. The highest portion of the upper reach in the Drakensberg is home to a variety of ungulates, including the Klipspringer (Oreotragus oreotragus), Mountain Reedbuck (Redunca fulvorufula), and Eland (Taurotragus oryx). Below the higher elevations of the Drakensberg peaks the Orange Mouse (Mus orangiae) is restricted to the Highveld grassland ecoregion, which can be considered the lower half of the upper reach of the Orange Basin.

Mountain Reedbuck, Drakensberg Range. Source: Thurner Hof The uppermost reaches of the Orange River develop within the The Drakensberg alti-montane grasslands and woodlands ecoregion which extends along the Drakensberg Mountain Range. The highest portion of the upper reach in the Drakensberg is home to a variety of ungulates, including the Klipspringer (Oreotragus oreotragus), Mountain Reedbuck (Redunca fulvorufula), and Eland (Taurotragus oryx). Below the higher elevations of the Drakensberg peaks the Orange Mouse (Mus orangiae) is restricted to the Highveld grassland ecoregion, which can be considered the lower half of the upper reach of the Orange Basin.

In this upper reach area, three river frogs: Sani Pass Frog (Amietia dracomontana), Large-mouthed Frog (Amietia vertebralis), and Cape River Frog (Amietia fuscigula) are endemic to rapidly-flowing streams of the alti-montane grassland. Other anurans found here are the Dwarf African Toad (Poyntonophrynus vertebralis), a toad found only in the Drakensberg alti-montane ecoregion and the Highveld grasslands of the middle reaches of the Orange River.

Grassy banks by the alti-montane mainstem and tributaries are also home to the recently described Cream-spotted Mountain Snake (Montaspis gilvomaculata), the only member of its genus. The high alpine moors are home to three endemic lizard species: Lang's Girdled Lizard (Pseudocordylus langi), Cottrell's Mountain Lizard (Tropidosaura cottrelli) and Essex's Mountain Lizard (T. essexi).

Middle reach fauna

The Critically Endangered Riverine Rabbit. Source: IUCN The fauna of the middle reach is relatively species-poor, and there are few strict faunal endemics, since most animals have extended their ranges into the Karoo from adjacent biomes. One species of small mammal is strictly endemic to the ecoregion: Visagie's Golden Mole (Chrysochloris visagiei, CR). Five other small mammals are near-endemic, Grant's Rock Mouse (Aethomys granti), Shortridge's Rat (Thallomys shortridgei, LR), the Orange basin endemic Riverine Rabbit (Bunolagus monticularis, CR), Gerbillurus vallinus and Petromyscus monticularis, LR.

The Critically Endangered Riverine Rabbit. Source: IUCN The fauna of the middle reach is relatively species-poor, and there are few strict faunal endemics, since most animals have extended their ranges into the Karoo from adjacent biomes. One species of small mammal is strictly endemic to the ecoregion: Visagie's Golden Mole (Chrysochloris visagiei, CR). Five other small mammals are near-endemic, Grant's Rock Mouse (Aethomys granti), Shortridge's Rat (Thallomys shortridgei, LR), the Orange basin endemic Riverine Rabbit (Bunolagus monticularis, CR), Gerbillurus vallinus and Petromyscus monticularis, LR.

The Black Rhinoceros (Diceros bicornis) is a Critically Endangered mammal found in the middle reach Karoo. Another special status vertebrate is the Riverine Rabbit (Bunolagus monticularis), classified as Endangered because of habitat destruction by agriculture. The Quagga (Equus quagga), a Nama Karoo near-endemic, was hunted to extinction in the 19th Century. Another charismatic mammal found in the middle reach Karoo is the Meerkat (Suricata suricatta).

Amphibians found in the middle reach Nama Karoo region are generally non-endemics: the African Clawed Frog (Xenopus laevis), Southern Ornate Frog (Hildebrandtia ornata), Angola River Frog (Amietia angolensis), Cape River Frog (Amietia fuscigula), Boettger's Dainty Frog (Cacosternum boettgeri), Red-spotted Namibia Frog (Phrynomantis annectens), Cryptic Sand Frog (Tomopterna cryptotis), Namaqua Dainty Frog (Cacosternum namaquense), Senegal Running Frog (Kassina senegalensis), Tschudi's African Bullfrog (Pyxicephalus adspersus) and Karoo Toad (Vandijkophrynus gariepensis).

The reptile fauna of the middle reach has at least ten species that are regarded as near-endemic to the Nama Karoo, but only a few are viewed as strictly endemic to the ecoregion, including Karoo Dwarf Chameleon (Bradypodion karrooicum) and Boulenger's Cape Tortoise (Homopus boulengeri). Many of the endemics, and some of the other species present, are relicts of past drier epochs when desert and savanna biomes expanded to link up with similar biomes in northeast Africa. One of the special status reptiles in the Karoo middle reach is the Lower Risk/Near Threatened Speckled Cape Tortoise (Homopus signatus).

Lower reach fauna

Bat-eared Foxes, southern Namibia. @ C.Michael Hogan There are almost 70 reptile species in the lower reach within the Namib Desert, of which five of these are strictly-endemic to the dry Namib Desert, and at least 20 taxa are nearly endemic. Several endemic reptiles, including the Wedge-snouted Sand Lizard (Meroles cuneirostris) and Koch's Chirping Gecko (Ptenopus kochi), remarkable in that they dive into the sand to escape danger. The Bat-eared Fox (Otocyon megalotis) occurs in both the lower and middle reaches of the watershed, and also has a disjunctive population in northeast Africa.

Bat-eared Foxes, southern Namibia. @ C.Michael Hogan There are almost 70 reptile species in the lower reach within the Namib Desert, of which five of these are strictly-endemic to the dry Namib Desert, and at least 20 taxa are nearly endemic. Several endemic reptiles, including the Wedge-snouted Sand Lizard (Meroles cuneirostris) and Koch's Chirping Gecko (Ptenopus kochi), remarkable in that they dive into the sand to escape danger. The Bat-eared Fox (Otocyon megalotis) occurs in both the lower and middle reaches of the watershed, and also has a disjunctive population in northeast Africa.

The Namib Desert is also home to numerous small rodents that occur among the rocky habitats, in the sand dunes and within the vegetation of the gravel plains. The Namib Dune Gerbil (Gerbillurus tytonis) is restricted to the southern portion of the Namib Desert. Grant’s Golden Mole (Eremitalpa granti VU) is near-endemic to the Namib Desert, its range extending down into South Africa from the moutn of the Orange River and north to Walvis Bay from the Orange River. This eyeless mole is well-adapted to the desert, able to swim through the loose, dry sands of the Namib dunes. The Namaqua Dune Mole Rat (Bathyergus janetta LR) is also near-endemic in the Namib Desert, with one isolated population occurring directly at the mouth of the Orange River. The Namib Long-eared Bat (Laephotis namibensis EN) is also an endemic to the Namib Desert.

While there are few amphibians in the lower basin, the Marbled rubber frog (Phrynomantis annectens) is a representative anuran who can survive in the Nama Karoo and Namib Desert part of the lower Orange River Basin; its survival strategy hinges on finding small pools in inselbergs or other rocky formations in order to breed.

Ecological conservation in the basin

In the headwaters reach habitats are relatively intact, especially in the stony areas. However, at lower elevations of the Drakensberg, areas not explicitly protected are severely threatened. Overgrazing pressure by domestic animals alters the ecosystem and makes the existing habitats vulnerable to encroachment by vegetation found in the lower elevation Karoo. It has been estimated that by 1986, more than 37 percent of the original extent of the Afromontane vegetation had been transformed, mostly from deforestation on lower slopes for agriculture and timber production. The stocking rates of grazing animals in Lesotho are now estimated to exceed carrying capacity by a factor of three.

The Namibian area of the Nama Karoo in the middle and lower and middle reach of the Orange Basin prehistorically had high mammalian species richness, but large mammals have been decimated by humans in southern Namibia and northwestern South Africa. These mammal distributions were altered by such overhunting, and left southern Namaland devoid of vulnerable species such as Lion and Plains Zebra (Equus burchelli). These two species have suffered a 95 percent range reduction even in the past 200 years. Today this area holds the national Namibian record for the most regional faunal extirpations

Some of the notable protected areas of the Orange River basin include the Sehlabathebe National Park at the headwaters of the Orange River in Lesotho. Near Kimberley, South Africa is the Mokala National Park. At the mouth of the Orange River in Namibia is the relatively newly created Sperrgebiet National Park, a site that has enjoyed de facto protection from the exclusion of people from an important diamond extraction zone.

Water usage

The water extracted from the Orange River for human use serves a basin population of 19 million people; Approximately 6.5 cubic kilometres per annum is extracted per annum The following percentage breakdown applies:

- Agriculture (64 percent)

- Urban demand (23 percent)

- Rural demand (7 percent)

- Mining and miscellaneous (6 percent)

The future of water usage in the Orange River system is questionable, since the rapidly growing human population continues to exert pressure on the water resources, notably for agricultural and domestic use. Additional concerns are placed by the excessive use of fertilizers, herbicides and pesticides which end up in the Orange River. Finally the inadequate sewage treatment facilities for the burgeoning population, and the addition of large dams create water quality and fish migration impacts respectively.

References

- T. Coleman & van Niekerk. 2007. Water Quality of the Orange River. Orange Senqu River Commission (ORASECOM).

- R. Froese, M.L.D. Palomares and D. Pauly. 2010. Species in the Orange River. Fishbase

- W. Giess. 1971. A preliminary vegetation map of South West Africa. Dintera 4: 1-114.

- C. Michael Hogan. 2014. Phrynomantis annectens, African Amphibians, ed. Breda Zimkus

- C.J. Swanevelder. 1981, Utilising South Africa's largest river: The physiographic background to the Orange River scheme, GeoJournal. vol 2 supp 2

- F. White. 1983. The vegetation of Africa, a descriptive memoir to accompany the UNESCO/AETFAT/UNSO Vegetation Map of Africa (3 Plates, Northwestern Africa, Northeastern Africa, and Southern Africa, 1:5,000,000). UNESCO, Paris.

- World Wildlife Fund & C. Michael Hogan. 2012. Nama Karoo. Encyclopedia of Earth. ed. Mark McGinley.

- C. Michael Hogan & World Wildlife Fund. 2012. Namib Desert. Encyclopedia of Earth. ed. Mark McGinley.

- World Wildlife Fund. 2013. Drakensberg alti-montane grasslands and woodlands. Encyclopedia of Earth. eds. Mark McGinley & C.Michael Hogan.