Northeast Australian Shelf/Great Barrier Reef large marine ecosystem

Location of the Northeast Australian Shelf/Great Barrier Reef Large Marine Ecosystem. Source: NOAA

Location of the Northeast Australian Shelf/Great Barrier Reef Large Marine Ecosystem. Source: NOAA The Northeast Australian Shelf/Great Barrier Reef large marine ecosystem (LME) is characterised by its tropical climate and characteristic anticlockwise gyre current system. It lies in the Pacific Ocean along the eastern margin of Australia. The LME is bounded by the Coral Sea to the east, and by the Torres Strait to the north. It is characterized by the South Equatorial Current, a part of the Pacific Ocean anticlockwise gyre, and by the Great Barrier Reef (GBR), a system of coral reefs that stretches 2000 kilometres (km) along Australia’s northeast coast. It is the largest system of coral reefs and related life forms in the world. Nutrient enrichment and mixing in this LME are due to tidal effects. Overfishing is a primary force driving LME change, with climate as the secondary driving force. LME book chapters and articles include Bradbury and Mundy, 1989, Kelleher, 1993, and Brodie, 1999.

Contents

- 1 Productivity

- 2 Fish and Fisheries

- 3 Pollution and Ecosystem Health

- 4 Socioeconomics

- 5 Governance

- 6 References

- 6.1 Articles and LME Volumes Bradbury, R.H. and C.N. Mundy, 1989. Large-scale shifts in Biomass of the Great Barrier Reef Ecosystem. In: Kenneth Sherman and Lewis M. Alexander, “Biomass yields and geography of Large Marine Ecosystems”, pp. 143-168. ISBN: 0813378443 (Northeast Australian Shelf/Great Barrier Reef large marine ecosystem) * Brodie, J. 1999. “Management of the Great Barrier Reef as a Large Marine Ecosystem.” In: Kenneth Sherman, Qisheng Tang, “Large Marine Ecosystems of the Pacific Rim-assessment, sustainability, and management.” Blackwell Science, pp 428-437. ISBN: 0632043369 * FAO, 2003. Trends in oceanic captures and clustering of large marine ecosystems - 2 studies based on the FAO capture database. FAO fisheries technical paper 435. 71 pages. * Kelleher, G. 1993. Sustainable Development of the Great Barrier Reef as a Large Marine Ecosystem. In “Large Marine Ecosystems-Stress, Mitigation, and Sustainability."Kenneth Sherman, Lewis M. Alexander and Barry D. Gold, Editors. Chapter 25, pp. 272-279. ISBN: 087168506X * Morgan, J., 1989. Large Marine Ecosystems in the Pacific Ocean. In: Biomass Yields and Geography of Large Marine Ecosystems, K. Sherman and L.M. Alexander, eds. AAAS Selected Symposium, 377-394. ISBN: 0813378443

- 6.2 Other References

- 6.3 Citation

Productivity

Tropical cyclones are common seasonal events in this region. There is high biological diversity in this LME, with high numbers of rare species. 350 species of hard coral are found on the Great Barrier Reef (GBR), along with 1500 species of fish, 240 species of seabirds, and at least 4000 species of mollusks (see Brodie, 1999). The physical and biological structure of the GBR is complex. For a map of the GBR region, (Kelleher, 1993, p. 273). Tidally-induced mixing in the GBR is a major contributor to the nutrient dynamics of this marine ecosystem. For more information on oceanographic processes in this LME, see Furnas. For large-scale shifts in biomass of the GBR, see Bradbury and Mundy. There has been a steady accumulation of knowledge and understanding of the structure and dynamics of this system. Bradbury and Mundy have reviewed the large-scale effects of Crown-of-thorns starfish outbreaks on the benthic community, and the propagation of effects into the fish and plankton communities. The hard corals are halved in abundance in the parts of the system where there is intense starfish activity.

For detailed information on the corals in this LME, see data collected by the University of British Columbia Fisheries Center. The Northeast Australian Shelf LME is considered a Category II, moderately high (150 to 300 grams of carbon per square meter per year) productivity ecosystem, according to SeaWiFS global primary productivity estimates. Ocean currents and wind systems along this coast inhibit the development of highly productive upwelling systems like those occurring along the western margins of North America, South America and Africa. Sources of nutrients to the LME are Coral Sea surface water, Coral Sea upwellings of deep sea water, terrestrial runoff, and atmospheric inputs.

Fish and Fisheries

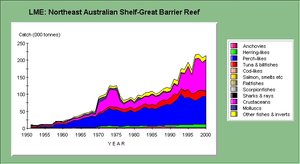

LME: Northeast Australian Shelf-Great Barrier Reef (Source: NOAA)

LME: Northeast Australian Shelf-Great Barrier Reef (Source: NOAA) These waters are relatively nutrient-poor and unable to sustain large fish populations. The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) 10-year trend shows a total catch of 10,000 tons in 1990, 14,000 tons in 1996, and 11,000 tons in 1999 (FAO, 2003). The average yearly catch is 12,000 tons. Catch trends are very diverse. There is a very high percentage of crustacean catches (more than half), and mollusks. On this narrow continental shelf, production depends on nutrient runoff and nutrient-rich upwellings. The trawl fishery (Fisheries and aquaculture) (Brodie, 1999) targets tiger prawns, banana prawns and king prawns. The annual catch for scallops and prawns is about 8000 tons. Scallops are caught in the southern section of the GBR Marine Park. The Torres Strait Prawn is a fully-exploited fishery. The Torres Strait Lobster is still somewhat underexploited. The Northeast Australia LME is driven by a predator, the Crown-of-Thorns starfish (Acanthaster planci), a coral-eating echiderm that has devastated reefs (Kelleher, 1993). The starfish has few predators in the environment. There is uncertainty as to whether the outbreaks are human induced or are a natural part of the ecological variability of the GBR (Brodie, 1999). Possible anthropogenic causes are the overfishing of Crown-of-Thorns predators such as fish or the triton shell, and enhanced nutrient runoff from coastal development.

Until recently, fisheries resources were usually managed in separate fishery units. Under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act), the Commonwealth Government now has a framework that helps it to respond effectively to current and emerging environmental problems, and to ensure that any harvesting of marine species is managed for ecological sustainability. For sustainable fishing issues in the GBR (Kelleher, 1993). The FAO provides information on Australia’s fisheries and the characteristics of the industry. The University of British Columbia Fisheries Center has detailed fish catch statistics for this LME. The data can be viewed in the graph above.

Pollution and Ecosystem Health

Aerial view of a portion of the LME. Source: NOAA

Aerial view of a portion of the LME. Source: NOAA The Crown-of-Thorns starfish (Acanthaster planci) has devastated reefs (Kelleher, 1993). The starfish has few predators in the environment. Outbreaks of this starfish may be human induced or are a natural part of the ecological variability of the GBR (Brodie, 1999). Possible anthropogenic causes are the overfishing of Crown-of-Thorns predators such as fish or the triton shell, and enhanced nutrient runoff (Surface runoff) from coastal development. For more information about the large-scale effects of Crown of thorns starfish outbreaks on the benthic community (Bradbury and Mundy, 1989). See the State of the Environment Report. The GBR is also threatened by increased shipping. A number of substantial ports line the GBR coastline (Brodie, 1999), and navigation in the Torres Strait is intense. Ballast water introductions of toxic dinoflagellates have caused serious ecological problems in other parts of Australia but so far no undesirable introduction has been detected in the GBR region. One significant anthropogenic impact on the GBR region is the change in the water quality of terrestrial runoff (Brodie, 1999). Excess nutrients can have a number of effects on coral and coral reef systems (Kinsey, 1991b). There is considerable evidence that reefs, particularly inshore fringing reefs, are now muddier and have less coral cover and more algal cover (Brodie, 1999).

There are environmental impacts on the GBR caused by tourism. Large numbers of people are engaged in recreational fishing, SCUBA diving and boating. Activities associated with the use of this kind of equipment have the potential to affect the environment through the pollution of water by boats and the disturbance of species and habitats (including mangroves). Recreational fishermen tend to target reef [[ecosystem]s] and remove larger predatory species. The effects of this selective removal of fish are largely unknown. Shore-based recreational fishing can have effects on shore populations of invertebrates that are collected for bait in intensively visited areas. A major source of environmental impacts is the provision of infrastructure to support tourism (airports, power generation facilities, accommodation, sewage treatment and disposal facilities, moorings, and marine transport, including high-speed ferries). Often the infrastructure is required in fragile or pristine environments that are susceptible to disturbance and fragmentation. Kelleher has reviewed water pollution control in the GBR.

Socioeconomics

The FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO)) provides information on Australia’s fisheries (Fisheries and aquaculture) and the socioeconomic benefits of the industry. Marine and [[coast]al]-based tourism is the main industry of the GBR, an internationally recognized tourist site and one of Australia’s 6 World Heritage Areas (Brodie, 1999). In the 1980s, tourism in the GBR was evaluated at 150,000 visitor-days. In the late 1990s, tourism was worth $1 billion, with 1.5 million visitor-days). Whale-watching occurs off the coast of Queensland. Shipping in the LME is a major activity. Extracting petroleum from the reef is permissible but not mining. With this level of usage, continuing tourism clearly depends on sustaining environmental and heritage values. Tourism can affect the lifestyle of community residents in ways they perceive as intrusive. Negative social impacts may include real or perceived increases in crowding, prices, or crime. Increased tourism may also result in increasing conflict between various uses of the marine and coastal areas. In terms of fisheries, for instance, there can be tensions between recreation, commercial and indigenous interests. Traditional fishing by Aborigines and Torres Strait islanders is confined to areas close to Aboriginal communities (Brodie, 1999). Kelleher has performed a comprehensive review of human uses of the Great Barrier Reef.

Governance

(Source: NOAA)

(Source: NOAA) The Northeast Australia LME lies off the coast of the State of Queensland. It extends to the Torres Strait, which separates Australia from Papua New Guinea. The main governance issues in this LME pertain to fisheries (Fisheries and aquaculture) management and to the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park. Under the offshore constitutional settlement between the Australian states and the federal government, the management of most fisheries within the GBR is the responsibility of the Queensland government (see Brodie, 1999). For more information on the governance of Australia’s fisheries, see the FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO)) website. Under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999, the Commonwealth Government has a framework that helps it to respond effectively to current and emerging environmental problems, and to ensure that any harvesting of marine species is managed for ecological sustainability. The GBR Marine Park Act was one of the first pieces of legislation in the world to apply the concept of sustainable development to the management of a large natural area. The GBR Marine Park Authority was established in 1975 to manage the multi-use park. The Authority aims to protect the natural [[ecosystem]s] of the GBR, and ensures that fishing does not have unacceptable ecological impacts on the fished areas and the reefs. For more information on the history and zoning system of the GBR Marine Park (Brodie, 1999; Kelleher, 1993). Compulsory pilotage in the area reduces the risk of collision with reefs.

On the national level, the Commonwealth Government developed a National Action Plan for Tourism in 1998. The Plan, which identifies conservation and careful management of the environment as essential to the long-term viability of the tourism industry, makes a commitment to ecologically sustainable tourism development and recognizes that environmental considerations should be an integral part of economic decisions. The marine tourism industry has produced a code of conduct that covers issues such as anchoring, removal of rubbish, fish feeding and preservation of World Heritage values. Australia declared a 200 nautical-mile Exclusive Economic Zone in 1978. Australia is party to the following international agreements: Antarctic-Environmental Protocol, Antarctic Treaty, Biodiversity, Climate Change, Endangered Species, Environmental Modification, Hazardous Wastes, Law of the Sea, Marine Dumping, Marine Life Conservation, Nuclear Test Ban, Ozone Layer Protection, Ship Pollution, Tropical Timber 83, Wetlands, and Whaling.

References

Articles and LME Volumes Bradbury, R.H. and C.N. Mundy, 1989. Large-scale shifts in Biomass of the Great Barrier Reef Ecosystem. In: Kenneth Sherman and Lewis M. Alexander, “Biomass yields and geography of Large Marine Ecosystems”, pp. 143-168. ISBN: 0813378443 (Northeast Australian Shelf/Great Barrier Reef large marine ecosystem) * Brodie, J. 1999. “Management of the Great Barrier Reef as a Large Marine Ecosystem.” In: Kenneth Sherman, Qisheng Tang, “Large Marine Ecosystems of the Pacific Rim-assessment, sustainability, and management.” Blackwell Science, pp 428-437. ISBN: 0632043369 * FAO, 2003. Trends in oceanic captures and clustering of large marine ecosystems - 2 studies based on the FAO capture database. FAO fisheries technical paper 435. 71 pages. * Kelleher, G. 1993. Sustainable Development of the Great Barrier Reef as a Large Marine Ecosystem. In “Large Marine Ecosystems-Stress, Mitigation, and Sustainability."Kenneth Sherman, Lewis M. Alexander and Barry D. Gold, Editors. Chapter 25, pp. 272-279. ISBN: 087168506X * Morgan, J., 1989. Large Marine Ecosystems in the Pacific Ocean. In: Biomass Yields and Geography of Large Marine Ecosystems, K. Sherman and L.M. Alexander, eds. AAAS Selected Symposium, 377-394. ISBN: 0813378443

Other References

- Bell, P.R.F. 1991. Status of eutrophication in the Great Barrier Reef lagoon. Marine Pollution Bull. 23:89-93.

- Brodie, J.E., 1995. Management of Sewage Discharges in the Great Barrier Reef marine Park. In O. Bellwood et al (eds), Recent advances in marine Science and Technology ’94. Townsville: James Cook University, pp. 457-465.

- Brodie, J., and Furnas, M., 1994. Long term monitoring programs for eutrophication and the design of a monitoring program for the Great Barrier Reef. In Proceedings of the Seventh International Coral Reef Symposium, Guam, 1:77-84.

- Furnas, Miles J., Land-sea interactions and oceanographic processes affecting the nutrient dynamics and productivity of Australian marine ecosystems.

- Hopley, D., 1982. The Geomorphology of the Great Barrier Reef: Quaternary Development of Coral Reefs. New York: Wiley-Interscience. ISBN: 0521853028

- Kinsey, D. 1991a. Can we resolve the nutrient issue for the reef? Search 22:119-121.

- Kinsey, D. 1991b. Water quality and its effect on reef ecology, land use patterns and nutrient loading of the Great Barrier Reef Region. Townsville. James Cook University, pp. 192-196.

- Lassig, B. and Englehardt, U., 1994. Crown-of-thorns starfish-another outbreak looms. Search 25(3):66-68.

- Maclean, J.L., 1989. Indo-Pacific red tides, 1985-1988. Marine Pollution Bull. 20(7):304-310.

- Pogonoski, J.J., D.A.Pollard and J.R.Paxton, 2002. Conservation Overview and Action Plan for Australian Threatened and Potentially Threatened Marine and Estuarine Fishes. Environment Australia, February 2002.

- Sainsbury, K.J., 1988. The ecological basis of multispecies fisheries, and management of a demersal fishery in tropical Australia. In Fishery population dynamics: The implications for management. pp. 349-382. J.A. Gulland (Ed.). John Wiley and Sons, New York. ISBN: 0471911518

- State of the Environment Report.

- Wolanski, E., 1994. Physical Oceanographic Processes of the Great Barrier Reef. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

| Disclaimer: This article contains information that was originally published by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). Topic editors and authors for the Encyclopedia of Earth have edited its content and added new information. The use of information from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) should not be construed as support for or endorsement by that organization for any new information added by EoE personnel, or for any editing of the original content. |