Ngorongoro

Contents

- 1 Ngorongoro Conservation Area, Tanzania

- 1.1 IntroductionNgorongoro Conservation Area (2°30'-3°30'S, 34°50'-35°55'E) is a World Heritage Site located 180 kilometers (Ngorongoro Conservation Area, Tanzania) (km) west of Arusha in the far north of Tanzania, adjoining the south-eastern edge of Serengeti National Park. An immense concentration of wild animals live in the huge and perfect crater of Ngorongoro. It is home to a small relict population of black rhinoceros and some 25,000 other large animals, largely ungulates, alongside the highest density of mammalian predators in Africa. Nearby are lake-filled Empakaai crater and the active volcano of Oldonyo Lenga. Excavations carried out in the Olduvai Gorge to the west, resulted in discoveries which have made the area one of the most important in the world for research on the evolution of the human species.

- 1.2 Geographical Location

- 1.3 Date and History of Establishment

- 1.4 Area

- 1.5 Land Tenure

- 1.6 Altitude

- 1.7 Physical Features

- 1.8 Climate

- 1.9 Vegetation

- 1.10 Fauna

- 1.11 Cultural Heritage

- 1.12 Local Human Population

- 1.13 Visitors and Visitor Facilities

- 1.14 Scientific Research and Facilities

- 1.15 Conservation Value

- 1.16 Conservation Management

- 1.17 IUCN Management Category

- 1.18 Further Reading

Ngorongoro Conservation Area, Tanzania

| Topics: |

IntroductionNgorongoro Conservation Area (2°30'-3°30'S, 34°50'-35°55'E) is a World Heritage Site located 180 kilometers (Ngorongoro Conservation Area, Tanzania) (km) west of Arusha in the far north of Tanzania, adjoining the south-eastern edge of Serengeti National Park. An immense concentration of wild animals live in the huge and perfect crater of Ngorongoro. It is home to a small relict population of black rhinoceros and some 25,000 other large animals, largely ungulates, alongside the highest density of mammalian predators in Africa. Nearby are lake-filled Empakaai crater and the active volcano of Oldonyo Lenga. Excavations carried out in the Olduvai Gorge to the west, resulted in discoveries which have made the area one of the most important in the world for research on the evolution of the human species.

Geographical Location

180 km west of Arusha in the far north of Tanzania, adjoining the south-eastern edge of Serengeti National Park. 2°30'-3°30'S, 34°50'-35°55'E.

Date and History of Establishment

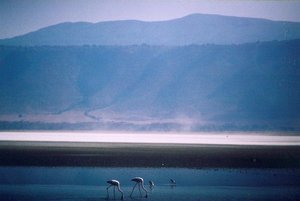

A lake in the Ngorongoro Crater. (Photo courtesy of Rachel Sandler. Source: Associated Colleges of the Midwest)

A lake in the Ngorongoro Crater. (Photo courtesy of Rachel Sandler. Source: Associated Colleges of the Midwest) - 1928: Hunting in the area prohibited;

- 1929: Serengeti Game Reserve created (228,600 hectares (ha));

- 1951: Ngorongoro made part of the new Serengeti National Park;

- 1959: The NCA established by Ordinance #413 to accommodate the existing Maasai pastoralists;

- 1975: The Ordinance redefined by the Game Parks Law Act # 14 to prohibit cultivation in the crater;

- 1981: Internationally recognized as a part of Serengeti-Ngorongoro Biosphere Reserve;

- 1985: The Ngorongoro Conservation & Development Program initiated by the government.

Area

828,800 ha. Contains the World Heritage site (809,440 ha). Contiguous to Serengeti National Park (1,476,300 ha) and 15 km northwest of Lake Manyara National Park (32,500 ha). Contained within the Serengeti-Ngorongoro Biosphere Reserve which covers 2,305,100 ha.

Land Tenure

Government. Administered by the Ngorongoro Conservation Authority (NCAA).

Altitude

~ 960 meters (m) to 3,648 m (Mt. Loolmalasin).

Physical Features

The Conservation Area rises 1,000 m from the plains of the eastern Serengeti, over the Ngorongoro Crater Highlands to the western edge of the Great Rift Valley. To the south are densely populated farmlands, to the north the Loliondo Game Control Reserve. The highlands have four extinct volcanic peaks over 3,000 m, including the massifs of Loolmalasin (3,648 m), Oldeani (3,188 m) and Lomagrut, the vulcanism of which dates from the late Mesozoic/early Tertiary periods. Ngorongoro Crater is the largest unbroken caldera in the world which is neither active nor flooded, though it contains a saline lake. Its floor, at an elevation of approximately 2,380 m, measures 17.7 by 21 km and is 26,400 (ha) in area (3% of the NCA), with a steep rim rising 400-610 m above the floor. The formation of the crater and highlands are associated with massive rifting which occurred to the west of the Great Rift Valley. The area also includes Empakaai Crater and Olduvai Gorge, famous for their geology and associated palaeotological studies. The highland forests form an important water-catchment for surrounding agricultural communities.

Climate

Because of the range in relief and the dynamics of its air masses, there is great variation within the climate of the area. In the highlands, it is generally moist and misty, while temperatures in the semi-arid plains can be as low as 2 degrees Celsius (°C), and often go up to 35°C. The annual precipitation falls between November and April and varies from under 500 millimeters (mm) on the arid plains in the west, to 1,700 mm on the forested slopes in the east, increasing with altitude.

Vegetation

The variations in climate, landforms and altitude have resulted in several overlapping ecosystems and distinct habitats. Within Tanzania the area is important for retaining uncultivated lowland vegetation, for the arid and semi-arid plant communities below 1,300 m, for its abundant shortgrass grazing and for the water catchment highland forests. Scrub heath, montane long grasslands, high open moorland and the remains of dense evergreen montane forests cover the steep slopes. Highland trees include peacock flower Albizzia gummifera, yellowwood Podocarpus latifolia, Hagenia abyssinica and sweet olive Olea chrysophylla. There is an extensive stand of pure bamboo Arundinaria alpina on Oldeani Mountain and pencil cedar Juniperus procera on Makarut Mountain in the west. Croton spp. dominate lower slopes. The upland woodlands containing red thorn Acacia lahai and gum acacia A. seyal are critical for protecting the watershed.

The crater floor is mainly open shortgrass plains with fresh and brackish water lakes, marshes, swamps and two patches of Acacia woodland: Lerai Forest, with co-dominants yellow fever tree Acacia xanthophloea and Rauvolfia caffra; and Laiyanai Forest with pillar wood Cassipourea malosana, Albizzia gummifera, and Acacia lahai. The undulating plains to the west are grass-covered with occasional umbrella acacia Acacia tortilis and Commiphora africana trees, which become almost desert during periods of severe drought. Blackthorn Acacia mellifera and zebrawood Dalbergia melanoxylon dominate in the drier conditions beside Lake Eyasi. These extensive grasslands and bush are rich, relatively untouched by cultivation, and support very large animal [[population]s].

Fauna

Giraffes in the Ngorongoro Conservation Area. (Source: Earlham College)

Giraffes in the Ngorongoro Conservation Area. (Source: Earlham College) A population of about 25,000 large animals, largely ungulates along with the highest density of mammalian predators in Africa, lives in the crater. These include black rhinoceros Diceros bicornis (CR), which have declined from about 108 in 1964-66 to between 11-14 in 1995, and hippopotamus Hippopotamus amphibius which are very uncommon in the area. There are also many other ungulates: wildebeest Connochaetes taurinus (7,000 estimated in 1994), zebra Equus burchelli (4,000), eland Taurotragus oryx, Grant's and Thomson's gazelles Gazella granti and G. thomsoni (3,000). The crater has the densest known population of lion Panthera leo (VU) numbering 62 in 2001. On the crater rim are leopard Panthera pardus, elephant Loxodonta africana (EN) numbering 42 in 1987 but only 29 in 1992, mountain reedbuck Redunca fulvorufula and buffalo Syncerus caffer (4,000 in 1994). However, since the 1980s the crater's wildebeest population has fallen by a quarter to about 19,000 and the numbers of eland and Thomson's gazelle have also declined while buffaloes increased greatly, probably due to the long prevention of fire which favors high fibrous grasses over shorter less fibrous types.

In summer enormous numbers of Serengeti migrants pass through the plains of the reserve, including 1.7 million wildebeest, 260,00 zebra and 470,000 gazelles. Waterbuck Kobus ellipsiprymnus mainly occur mainly near Lerai Forest; serval Felis serval occur widely in the crater and on the plains to the west. Common in the reserve are lion, hartebeest Alcelaphus buselaphus, spotted hyena Crocuta crocuta and jackal Canis aureus. Cheetah Acinonyx jubatus (VU), though common in the reserve, are scarce in the crater itself. Wild dog Lycaon pictus (EN) has recently disappeared from the crater and may have declined elsewhere in the Conservation Area as well. Golden cat Felis aurata has recently been seen in the Ngorongoro forest.

Over 500 species of bird have been recorded within the NCA. These include ostrich Struthio camelus, with white pelican Pelicanus onocrotalus, and greater and lesser flamingo Phoenicopterus ruber and P.minor on Lake Makat in Ngorongoro crater, Lake Ndutu and the Empakaai crater lake where over a million birds forgather. There are also lammergeier Gypaetus barbatus, Ruepell's griffon, Gyps ruepelli (110) Verreaux's eagle Aquila verreauxii, Egyptian vulture Neophron percnopterus, pallid harrier Circus macrourus, lesser falcon Falco naumanni (VU), Taita falcon F. fasciinucha, kori bustard Choriotis kori, Fischer's lovebird Agapornis fischeri, rosy-breasted longclaw Macronyx ameliae, Karamoja apalis Apalis karamojae (VU), redthroated tit Parus fringillinus and Jackson's whydah Euplectes jacksoni. Sunbirds in the highland forest include the golden winged sunbird Nectarinia reichenowi and eastern double collared sunbird N. mediocris. Other waterbirds found on Lake Eyasi include yellowbilled stork Mycteria ibis, African spoonbill Platalea alba, avocet Recurvirostra avosetta and greyheaded gull Larus cirrocephalus. The butterfly Papilio sjoestedti, sometimes known as the Kilimanjaro swallowtail, flies in the montane forests. It has a very restricted range but is well protected in national parks.

Cultural Heritage

The area has palaeotological and archaeological sites from a wide range of eras. The four major sites are Olduvai gorge, Laetoli and Lake Ndutu all near the Serengeti and the Nasera rock shelter in the Gol Mountains. The variety and [[rich]ness] of the fossil remains, including those of early hominids, has made the area one of the most important in the world for research on the evolution of the human species. Olduvai Gorge yielded valuable remains of early hominids including, in 1959, Australopithecus boisei (Zinthanthropus) 1.75 million years old, also Homo habilis as well as fossil bones of many extinct animals. At Laetoli nearby, fossil footprints of an upright hominid 3.6m years old were found in 1975.

Local Human Population

The Maasai, nomadic cattle herders, entered the crater around 1840. Since the multi-use protection of the area was proposed in 1959, the population of the area has exploded beyond the numbers of cattle able to support it without farming, aggravating tensions with the conservation-oriented administration. In 1966 there were 8,700 people in the NCA. In 1994, the Natural Peoples World estimated the Maasai population at about 40,000 (one quarter of those living in Tanzania), with some 300,000 head of livestock which graze approximately 70-75% of the conservation area. But mobile pastoralists are difficult to count, and Leader-Williams et al. in 1996 put the figure at 26,000 pastoralists with 285,000 head of cattle. Since their eviction by the NCAA in 1974, there are no inhabitants in Ngorongoro and Empakaai Craters or the forest. In general, livestock numbers are declining and the Maasai are growing poorer.

Visitors and Visitor Facilities

The spectacular wildlife, geology and archaeology of Ngorongoro-Serengeti are major African tourist attractions spread across an area the size of Rwanda or Sicily. About 24% of all tourists visiting the parks of northern Tanzania stop at Ngorongoro. These totaled 35,130 in 1983, 140,000 in 1989 in at least 30,000 vehicles and, according to the Chief Conservator, there were between 1998 and 2001, 562,205 visitors of whom 202,957 (36%) were Tanzanian. The damage inflicted by these numbers is considerable. There are four lodges on the crater rim and one at Lake Ndutu on the edge of Serengeti. Vehicles and guides can be hired from the Conservation Authority to enter the crater. There is an interpretive center at the Lodoare entrance and another at Olduvai, which focuses on the interpretation of the Gorge and its excavations. An information center to promote wildlife tourism to local Tanzanians was opened in Arusha in 2002.

Scientific Research and Facilities

The area, with Serengeti, is one of the best studied areas in Africa. Work based at SWRC in the contiguous Serengeti National Park, formerly the Serengeti Research Institute, include the monitoring of climate, vegetation and animal [[population]s]. The level of research into human and range ecology is low. Long-term studies in the crater have been on lion, serval, rhinoceros and elephant behavioral ecology. From 1988, the Ngorongoro Ecological Monitoring Programme has been individually identifying black rhinoceros, and monitoring breeding and movement patterns. Seronera Research Centre provides a research station and accommodation for scientists. There is a small research cabin within the crater. The IUCN/SSC Antelope Specialist Group has just reported on the decline of the crater's antelope species and increase in buffaloes.

Conservation Value

Ngorongoro is the largest intact, inactive and unflooded caldera in the world. The conservation area has one of Africa's largest aggregations of wildlife. It is home to a small and isolated relict of the black rhino population,and discoveries in the area round Olduvai gorge is one of the most important in the world for research on the evolution of the human species.

Conservation Management

Flamingos in the Ngorongoro Conservation Area. (Source: Williams College)

Flamingos in the Ngorongoro Conservation Area. (Source: Williams College) Ngorongoro was first established as a conservation area which would accommodate the existing Maasai. The Ordinance of 1959 created the NCAA. Its objectives were to conserve and develop the NCA's natural resources, promote tourism, and safeguard and promote the interests of the Maasai. By 1960 a draft management plan was prepared. On Independence in 1961 Prime Minister Julius Nyerere issued the Arusha Manifesto of support for the preservation of the country's wildlife. The government conducted a pioneer experiment in multiple land use (one of few such areas in Africa) which attempted to reconcile the interests of wildlife conservation and Maasai pastoralism. It failed through a lack of rapport between government officials and the tribesmen who were seen as degrading the land and competing with the wildlife for the resources of the crater. In 1974 tribesmen farmers living in the craters were summarily evicted. The removal of these natural (and low-cost) guardians resulted in an increase of poaching and the subsequent near extinction of the rhinoceros population. The 1975 Ngorongoro Conservation Area Ordinance was redefined and in 1976 cultivation was banned as incompatible with conservation. Between 1984 and 1989 the property was on the WHC danger list as a result of these conflicts.

In 1985, following the Serengeti Workshop, convened by the Ministry of Natural Resources and Tourism, the Government of Tanzania and IUCN initiated the Ngorongoro Conservation and Development Project. Its main objectives were to identify the requirements for long-term conservation of the area by assessing land use pressures in and adjacent to the conservation area; to determine the development needs of resident pastoralists; to review and evaluate management options; to formulate conservation and development policies to fulfill the needs of both local Maasai people and conservation priorities; and to develop proposals for follow-up activities. Zones were defined for scenic and archaeological quality, wildlife forest, pastureland and infrastructural development. Since the problems were identified, the NCAA has set more funds aside for appropriate solutions, veterinary services and water have been provided and the relationship between the tribesmen and the NCAA has been improved by the establishment of a Community Development Department and a joint Management-Resident Representative Council.

The contiguous and nearby protected areas provide key feeding grounds for a number of species such as buffalo, wildebeest, zebra and Thomson's gazelle that migrate out of the crater during periods of drought, and much effort is made to prevent migration routes from being encroached on by settlements and agricultural developments. Efforts have been made to control poaching with the aid of the Frankfurt Zoological Society, the African Wildlife Foundation, the Tanzania Wildlife Protection Fund, WWF and the police. IUCN/WWF Project #1934 was set up in 1981 to combat poaching of rhinoceros in the Lake Eyasi area and two vehicles and radios were provided. In an attempt to reduce pressure on the natural forest for fuel wood the NCAA produce up to 40,000 tree seedlings annually. Ngorongoro Conservation Area Management Plan proposals have been submitted but were rejected by the Chief Conservator because the proposed plan was regarded as going beyond its terms of reference.

Management Constraints

There has been continued poaching of black rhinoceros and leopard, which is difficult to suppress effectively due to the lack of equipment and fuel, rough terrain and low staff morale. The rhinoceros population, owing to its small size, is extremely vulnerable to poaching, and faces genetic threats from inbreeding and loss of genetic variation. The spread of malignant catarrh fever which kills cattle, although it has little effect on wildebeest, has been reduced as wildebeest numbers have markedly decreased as have other antelope numbers. There is a problem with securing water, caused by the neglect of the dams, boreholes and pipelines installed during the 1950s and 1960s and by the road widening and canal works which have blocked and diverted water from streams and the Gorigor swamp either to tourist lodges or directly to Lake Makat, no longer flooding the crater during the rains.

Grassland areas are also degrading with the extensive spread of the unpalatable grass Eleusine jaegeri, and other weeds which compete aggressively with palatable grasses, especially the poisonous Mexican poppy Argemone mexicana which rapidly invades overgrazed land, crowding out both crops and the native plants which sustain the existing wildlife. The invasions may be partly due to the prevention of fire and overgrazing due to drought which may contribute as much as emigration, disease or disturbance by tourists to the change in the animal populations. The forests to the north-east are increasingly threatened by fuelwood gathering both by people living in the Conservation Area and in villages in the Karatu and Kitete areas along the eastern boundary. A number of poorer Maasai from the area make a living collecting honey from wild bee colonies in the forest, frequently burning trees in the process. About five percent of the area has been degraded by trampling and overgrazing, and there is a threat from vehicle-tracks becoming excessively enlarged, mainly by tourist activity.

Conflicts over land-use have increased in recent years as the Maasai became more numerous and sedentary, turning to cultivation to supplement their previously cattle-based diet. The decline in numbers of livestock was aggravated by inadequate veterinary services, which the NCAA had difficulties providing as income from tourism decreased. In the 1960s each man had 12 cattle to sustain him; by 1989 this had become five. In response to the scarcity of food, residents were allowed to practice cultivation on a temporary basis. More than 2,200 ha were estimated to be under cultivation in 1993. Much of this was on areas too steep for agriculture, causing erosion. Encroachment on the slopes of Empakaai and Kapenjiro has been so extensive that they may be excised from the conservation area. This has had serious impacts on the vegetation which protects water catchments, and on wildlife corridors. In addition, the Chief Conservator reported that disease followed by a plague of flies had killed at least 600 animals in 2000.

Priorities identified by the community include food security, livestock health and infrastructure such as better water supply, housing, clinics and schools. Some of these have been provided to try to lessen conflicts and in 2002 the NCAA was reported to have set up an NGO, Ereto, to support local communities with free services. But there is still a lack of a clear management policy and commitment to human development on the same level as the conservation of the wildlife. The uncertainty caused by this has led to under-investment in the area, which the employment and empowerment of local people would begin to improve. But in 2001 the World Heritage Committee urged a moratorium on further development until an assessment of environmental impacts, especially of water resources by a hydrological survey, had been completed. It also recommended a scientific overseeing committee, ecologically based burning, mitigation of road works, an improved road plan and limiting the effect of tourist numbers.

Staff

Some 360 staff in 1994 (National Park Service, pers. comm.,1995).

Budget

Approximately 90% (Tsh3-4billion or US$3.5-4.,000,000) of the annual budget is derived from visitor entrance fees. During the 1980s and 90s, development has been generously subvented via the IUCN by several national and international organizations, especially the Frankfurt Zoological Society.

IUCN Management Category

- VI (Managed Resource Protected Area)

- Biosphere Reserve

- Natural World Heritage Site inscribed in 1979. Natural Criteria ii, iii, iv

Further Reading

- Anon. (1981). A Revised Development and Management Plan for the Ngorongoro Conservation Area. Bureau of Resource Assessment and Land Use Planning, Dar-es-Salaam, Tanzania.

- Arhem, K., Homewood, K. & Rodgers, A. (1981). A Pastoral Food System: The Ngorongoro Maasai in Tanzania. Bureau of Resource Assessment and Land Use Planning, Dar-es-Salaam.

- Arhem, K. (1981). Maasai Pastoralism in the Ngorongoro Conservation Area; Sociological and Ecological Issues. Bureau of Resource Assessment and Land Planning. Dar-es-Salaam.

- Arusha Times, (2001). Deadly insects plagued crater. Arusha Times, March 10, Arusha.

- Dirschl, H. (1966). Management and Development Plan for Ngorongoro. Ministry of Agriculture, Forests and Wildlife, Dar-es Salam

- Eggeling, W. (1962). The Management Plan for the Ngorongoro Conservation Area Authority, Ngorongoro Conservation Area Authority. Ngorongoro Crater.

- Estes, R. & Small, R. (1981). The large herbivore populations of Ngorongoro Crater. Afr. J. Ecol. 19(1-2): 175-185.

- Fishpool, L.& Evans, M.(eds) (2001). Important Bird Areas for Africa and Associated Islands. Priority Sites for Conservation. Pisces Publications and Birdlife International, Newbury and Cambridge, U.K. BLI Conservation Series No.11. ISBN: 187435720X.

- Fosbrooke, H. (1990). Ngorongoro at the crossroads. Kakakuana 2 (1):11-14. Mweka,Tanzania.

- Frame, G. (1982). Wild Mammal Survey of Empakaai Crater Area. Tanzanian Notes and Records No. 88 and 89: 41-56.

- Herlocher, D. & Dirschl, H. (1972). Vegetation Map. Canadian Wildlife Services, Report Series 19.

- Homewood, K. & Rodgers, W. (1984). Pastoralist Ecology in Ngorongoro Conservation Area, Tanzania. Pastoralist Development Network Bulletin of the Overseas Development Institute, London. No. 17d: 1-27.

- IUCN (1985). Threatened natural areas, plants and animals of the world. Parks10(1): 15-17.

- IUCN (1987). Ngorongoro Conservation and Development Project. Workplan of Activities. Unpub. report. 10 pp.

- IUCN/WWF Project 1934. Tanzania, Anti-poaching Camp, Lake Eyasi.

- IUCN/SSC Antelope Specialist Group (2002). Ngorongoro Crater Ungulate Study 1996-1999. Final report for the Ngorongoro Conservation Area Authority.

- IUCN (2002). Report on the State of Conservation of Natural and Mixed Sites Inscribed on the World Heritage List. Gland, Switzerland

- Kangera,R. (2002). Time, life and tides in Ngorongoro Park. Arusha Times, 31 May. Arusha.

- Kayera, J. (1988). Balancing Conservation and Human Needs in Tanzania: the Case of Ngorongoro. Unpublished report. 5pp.

- Lamotte, M, (1983). The undermining of Mount Nimba. Ambio XII(3-4): 174-179

- Leader-Williams, N., Kayera, J. & Overton, G.(eds). (1996) Community-based Conservation in Tanzania. IUCN Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge, UK. ix + 266pp. ISBN: 283170314X.

- Mbakilwa,I. (2002). NCAA takes action to promote local tourism. Arusha Times,13 April, Arusha.

- Moehlman, P., Amato, G. & Runyoro, V. (1996) Genetic and demographic threats to the black rhinoceros population in the Ngorongoro Crater. Conservation Biology 10(4):1107-1114

- Mturi, A. (1981). The Archaeological and Palaeotological Resources of the Ngorongoro Conservation Area. Ministry of National Culture and Youth, Dar-es-Salaam.

- Nuhu, A. (2001). Killer disease decimates hundreds of animals. Arusha Times, 1Mar. Arusha.

- Perkin, S. & Mshanga, P. (1992). Ngorongoro: seeking a balance between conservation and development, in Proceedings of the IVth World Congress on National Parks and Protected Areas, Caracas, Venezuela, Feb.1992.

- Prins, H. (1987). Nature conservation as an integral part of optimal landuse in East Africa: the case of the Masai Ecosystem in Northern Tanzania. Biological Conservation 40: 141-161.

- Rodgers, W. (1981). A Background Paper for a Revised Management Plan for the Ngorongoro Conservation Area Authority. Department of Zoology, University of Dar-es-Salaam.

- Saibull, S. & Carr, R. (1981). Herd and Spear. The Life of Pastoralists in Transition. Collins, London.

- Saibull, S. (1968). Ngorongoro Conservation Area. East African Agric. For. Research Journal. Vol. 33 Special Issue.

- Saibull, S.ole (1978). The Policy Process in the Ngorongoro Conservation Area. Status of the Area Looked at Critically. Tanzanian Notes and Records No. 83.

- Said, M.,Chunge,R.,Craig, G.,Thouless, C.,Barnes, R.& Dublin, H. (1995) African Elephant Database, 1995. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland, 225 pp. ISBN: 283170295X.

- Serengeti Wildlife Research Centre (1993). Scientific Report 1990-1992. Serengeti Wildlife Research Centre.

- Tanzania Wildlife Conservation Monitoring (TWCM). (1993) Cultivation in Ngorongoro Conservation Area. Ip

- Taylor, M. (1988). Ngorongoro Conservation Area: a Report to IUCN Nairobi. Country Commission. 24 pp.

- Thorsell, J. (1985). World Heritage report - 1984. Parks 10(1): 8-9.

- UNESCO World Heritage Committee (2002) Report on the 26th Session of the World Heritage Committee, Paris

| Disclaimer: This article is taken wholly from, or contains information that was originally published by, the United Nations Environment Programme-World Conservation Monitoring Centre (UNEP-WCMC). Topic editors and authors for the Encyclopedia of Earth may have edited its content or added new information. The use of information from the United Nations Environment Programme-World Conservation Monitoring Centre (UNEP-WCMC) should not be construed as support for or endorsement by that organization for any new information added by EoE personnel, or for any editing of the original content. |