Biological diversity in New Zealand

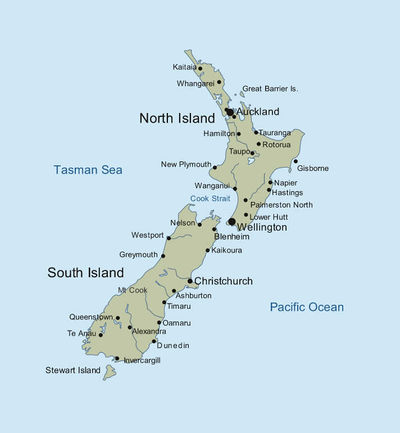

Map of New Zealand (Source: http://help.zeald.com/) New Zealand is linked biogeographically with New Caledonia via the undersea Norfolk Rise. Both New Zealand and New Caledonia split away from Gondwanaland at the same time and did not separate from each other until around 40 million years ago. Both hotspots are "ancient life-rafts" which have been largely isolated and have evolved unique flora and fauna.

Map of New Zealand (Source: http://help.zeald.com/) New Zealand is linked biogeographically with New Caledonia via the undersea Norfolk Rise. Both New Zealand and New Caledonia split away from Gondwanaland at the same time and did not separate from each other until around 40 million years ago. Both hotspots are "ancient life-rafts" which have been largely isolated and have evolved unique flora and fauna.

New Zealand ranges in latitude from subtropical to subantarctic, and is a land of varied landscapes, with rugged mountains, rolling hills and wide alluvial plains. It is a tectonically active hotspot with frequent earthquakes and volcanic activity. About 75 percent of the hotspot's land area is above 200 metres in altitude, reaching a maximum of 3700 metres on Aoraki (Mount Cook).

Climate is highly variable throughout the islands and has played a key role in biodiversity distribution. Annual rainfall ranges from 12,000 millimetres (one of the highest rainfall rates in the world) on the western slopes of the Southern Alps, to less than 300 millimeters in the rainshadow areas east of the Southern Alps. The Kermadec Islands have a subtropical climate, with warm, moist conditions throughout the year, while the Chatham Islands have a cloudy, humid climate, with cool, wet winters and warm, usually dry summers.

New Zealand's forests have been greatly depleted, but, of the remaining forests, the most impressive are those of giant New Zealand kauri (Agathis australis), which are restricted to the far north. Other forests on North Island are dominated by angiosperms, while those in the southern portion of the island and on South Island are dominated by Gondwanan gymnosperms of the family Podocarpaceae and southern beeches (Nothofagus spp.). The forests on the western flanks of the Southern Alps are among the most extensive temperate rainforests on Earth. Other vegetation types include scrub and shrublands, and snow grasses (Chionochloa spp.) above the timberline. At higher altitudes, the vegetation is characterized by cushion plants, many of them endemic and including the peculiar and distinctive "vegetable sheep" (Raoulia and Hastia spp.), which are highly compacted shrubs of the family Asteraceae.

Contents

Unique and Threatened Biodiversity

As is true of the other fragments of Gondwanaland - Madagascar, Australia, and New Caledonia -- New Zealand has remarkable levels of endemism among plants, birds and reptiles.

Plants

View of Cyathea smithii in Leith Saddle Track north of Dunedin. The Wheki-Ponga tree fern, or Soft Tree Fern, (Cyathea smithii) is endemic to New Zealand and occurs on North, South, Stewart and Chatham islands. (Source: André Richard Chalmers (Own work) (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0), via Wikimedia Commons) Plant endemism is very high in New Zealand. Nearly 1900 of about 3400 species of vascular plants are endemic. Endemism also extends to the genus level; 35 plant genera are found nowhere else in the world. An example is the endemic monotypic genus Desmoschoenus spiralis or Pingao golden sand sedge, a coastal plant used by the Maori people in traditional building construction.

View of Cyathea smithii in Leith Saddle Track north of Dunedin. The Wheki-Ponga tree fern, or Soft Tree Fern, (Cyathea smithii) is endemic to New Zealand and occurs on North, South, Stewart and Chatham islands. (Source: André Richard Chalmers (Own work) (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0), via Wikimedia Commons) Plant endemism is very high in New Zealand. Nearly 1900 of about 3400 species of vascular plants are endemic. Endemism also extends to the genus level; 35 plant genera are found nowhere else in the world. An example is the endemic monotypic genus Desmoschoenus spiralis or Pingao golden sand sedge, a coastal plant used by the Maori people in traditional building construction.

The fern Loxoma cunninghamii is one of the hotspot's "living fossils." Together with three species from Central America, L. cunninghamii constitutes the family Loxomataceae, whose closest relatives existed 60 million years ago. The hotspot also has one endemic family, the Ixerbaceae, which is represented by a single species (Ixerba brexiodes).

Vertebrates

Birds

Nearly 200 bird species regularly occur in New Zealand, almost 90 of which (44 percent) are endemic. Not surprisingly, five Endemic Bird Areas identified by BirdLife International occupy nearly the entire area of the country. The hotspot also has 17 endemic bird genera and three endemic bird families, Acanthisittidae, Apterygidae, and Callaeidae. Moreover, it is the only hotspot to have an endemic bird Order, represented by the endearing, flightless kiwis (Apterygiformes), also the national bird of New Zealand.

Unfortunately, New Zealand's existing bird diversity represents only a fraction of the birds that once occupied the island. The hotspot has suffered 20 bird extinctions since 1500, including Stephens Island wren (Traversia lyalli), the only case in which an entire species was rendered extinct by the predatory instincts of a single introduced cat. Other historically extinct species include the giant flightless moas, which could grow to more than 3.5 metres in height, the bizarre flightless adzebill (Aptornis), which weighed up to 10 kilograms and bears no resemblance to any other known bird, and the largest eagle in the world, Haast's eagle (Harpagornis moorei), which preyed on moa.

A recent staggering development was the 2003 rediscovery of the New Zealand storm petrel (Oceanites maorianus, CR) in waters just off North Island. The 2003 sightings were the first records of this species, which had previously been known only from fossil material and three nineteenth-century specimens.

500px Kakapo, (Strigops habroptilus), showing how the bird's plumage acts as camouflage in vegetation. Photo taken on Codfish Island (Whenua Hou), New Zealand. (By Mnolf (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html), CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/) or CC-BY-SA-2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0), via Wikimedia Commons) A number of other species are highly threatened today, including the kakapo (Strigops habroptilus, CR), a large, nocturnal, flightless parrot, which has suffered habitat destruction and extensive predation by introduced species like stoats and dogs. By 1976, the known population was 18 birds, all males, and all in Fiordland. In 1977, a rapidly declining population was discovered on Stewart Island, and so between 1980 and 1992 some 60 surviving birds were translocated to offshore islands, and currently survive on Maud, Inner Chetwode, Codfish, and Pearl Islands. In 1999, the population numbered 26 males and 36 females, with 50 animals of reproductive age. The population has since stabilized and is increasing.

All four species of kiwi are also threatened: tokoeka (Apteryx australis, VU), great spotted kiwi (Apteryx haastii, VU), brown kiwi (Apteryx mantelli, EN), and little spotted kiwi (Apertyx owenii, VU). These unusual birds are much smaller cousins of ostriches, emus, and rheas. Kiwis are mammal-like birds, with hairy feathers, sensory whiskers, an acute sense of smell, and short, squat bodies. They have marrow-filled bones (rather than hollow bones like other birds) and lay an egg that is 25 percent of their own body weight, which incubates for two to three months before hatching.

Finally, New Zealand also has the most diverse seabird community in the world, with around 80 species known to breed here. At least three-quarters of the world's penguin species breed in the New Zealand region, including the threatened endemic yellow-eyed penguin (Megadyptes antipodes, EN).

Mammals

Both land mammal species native to the hotspot are endemic bats, one of which is the only living representative of the endemic bat family Mystacinidae: the New Zealand lesser short-tailed bat (Mysticina tuberculata, VU). This bat species is an oddity in that it walks about on all fours on the ground in predator-free environments. Its relative, the greater short-tailed bat (Mystacina robusta) is Extinct. The second land mammal species found in New Zealand is the long-tailed wattled bat (Chalinolobus tuberculatus, VU), which has suffered significant population declines recently. THe Hooker's sea lion (Phocarctos hookeri, VU) also occurs in this hotspot.

Reptiles

Nearly 40 species of reptiles are found in New Zealand, and all are unique to the islands; the fauna comprises geckos and skinks only, and there are no native snake species. In addition, a remarkable five of six reptile genera are endemic to the hotspot. The region also boasts an entire endemic order, the tuataras (Order Rhynchocephalia). The tuataras resemble iguanas and are primitive species that have existed since the dinosaur age, famous for their well-developed third eye. Although tuataras once ranged throughout much of the hotspot, the arrival of the Polynesia rat (Rattus exulans) greatly reduced their numbers. Two remaining species, Sphenodon punctatus and S. guntheri, are confined to 30 predator-free offshore islands where the New Zealand Department of Conservation is hoping the species' small populations will rebound.

Amphibians

Amphibians are represented in New Zealand by just four primitive frog species of the endemic family Leiopelmatidae. All four species are threatened, among them Archey's frog (Leiopelma archeyi, CR), which occurs on North Island in the Whareorino range in the west and Coromandel ranges in east, and has been severely affected by chytrid fungus.

Freshwater Fishes

Of the nearly 40 freshwater fish species native to New Zealand, about 25 (64 percent) are found nowhere else. The fish fauna is dominated by members of the family Galaxiidae, a group of coolwater trout-like fishes restricted to the southern tips of South America, Africa, Australia and New Zealand. Nearly 20 of the more than 50 galaxiid species known worldwide are found in New Zealand, and all but a few are endemic to the hotspot.

Invertebrates

Additional research on New Zealand's invertebrate fauna is needed. The hotspot is home to 28 species of gastropods for which IUCN Red List assessments are available, six of which are considered to be Data Deficient by the IUCN Red List. Two species of land snail are threatened, Rhytida clarki (CR) and R. oconnori (CR), and a further three species of flax snails may soon be (Placosylus ambagiosus (VU), P. bollonis (VU), P. hongii (VU)). Six species are recorded as being Extinct, all from Norfolk Island.

A distinctive element of the New Zealand biota is the widespread occurrence of gigantism. Although some of the giant forms include the now extinct flightless moas and Haast's eagle, this element is still noticeable in some giant insects, myriapods, flatworms, land snails, centipedes, slugs, and earthworms. The world's heaviest insect, the weta or wingless cricket of Little Barrier Island (Hauturu) weighs up to 70 grams and is one of 12 species of Deinacrida, the ancestors of which roamed the Jurassic forests.

Human Impacts

Although people came to New Zealand relatively late - only about 700-800 years ago - human impact on the land and natural ecosystems has been extensive. The first great impact was from hunting, fishing, and gathering, which caused the extinction of native bird species such as the giant moas and eagles.

However, an even greater threat to the native biodiversity of New Zealand was the introduction of invasive alien species. When Europeans arrived on the islands in the early nineteenth century, they brought with them 34 exotic mammal species (including brush-tailed possums, rabbits, cats, goats, stoats and ferrets) and hundreds of invasive (Alien species) weedy plant species. In conjunction with the impact of hunting (and also extensive habitat destruction), the last two hundred years have witnessed the extinction of 16 land birds, one endemic bat, one fish, at least a dozen invertebrates, and ten plants. Several other species survive only in tiny populations on offshore islands.

Today, invasive species remain an important threat to New Zealand's biodiversity, but large-scale habitat destruction, through deforestation, wetland drainage and ecosystem degradation, represents as serious an issue. In terms of natural habitat, it is estimated that remaining indigenous habitat in more or less primary condition amounts to 35,000 km2 of forest (down from roughly 230,000 km2), 15,000 km2 of native grassland-scrub, 4000 km2 of wetlands and other aquatic systems, 2600 km2 of smaller island ecosystems, 1800 km2 of alpine systems, and about 1000 km2 of Coastal Systems, for a total of 59,400 km2 (or 22 percent of the land surface of the country).

Conservation Action and Protected Areas

There are two remaining species of tuatara, ancient reptiles that have existed since the dinosaur age. They only occur on predator-free offshore islands in the New Zealand Hotspot. Pictured here is Henry, the world's oldest Tuatara in captivity, at Invercargill, New Zealand. (By KeresH (Own work) (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0), via Wikimedia Commons)

There are two remaining species of tuatara, ancient reptiles that have existed since the dinosaur age. They only occur on predator-free offshore islands in the New Zealand Hotspot. Pictured here is Henry, the world's oldest Tuatara in captivity, at Invercargill, New Zealand. (By KeresH (Own work) (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0), via Wikimedia Commons) New Zealand has a strong history of conservation legislation, dating back nearly 150 years. Most conservation laws are administered by the Department of Conservation, the main government agency responsible for the protection and sustainable use of biodiversity. Yet, the true conservation successes in New Zealand have resulted from the hard work of exceptionally talented, focused and energetic individuals who have made the conservation of threatened species successful at the ground level. Richard Henry, back in the 1880s, started this trend by trying to save the kakapo by translocation to islands. The practical, experimental and field-based focus of conservation, which grew out of the old Wildlife Service in the 1960s and 1970s, has been a major factor in achieving conservation in this hotspot.

The country's first national park was established in 1887. Today, 74,000 km2 of land (27.5 percent of the land area) is officially protected, including 3,345 protected areas in IUCN categories I to IV covering 22 percent of the land area. Most of these parks and larger reserves are in mountainous areas (such as the Southern Alps), while lowland habitats are not as well protected. However, a number of protected areas have been established especially to protected threatened species, including many of the offshore and outlying islands ranging from the large subantarctic Auckland and Campbell Island groups, Little Barrier (Hauturu), and Kapiti, to the warm temperate Kermadec Islands.

However, while formal habitat protection is important, active pest management is required if further extinctions are to be avoided, particularly given the threat of invasive species on the native fauna and flora. Conservation practitioners in New Zealand have earned an international reputation for their achievements in eradicating invasive mammals from islands and, more recently, controlling animal and plant pests at "mainland" sites. Twelve species of pest mammals and one predatory bird have been successfully eradicated from offshore and oceanic islands in the New Zealand region.

Significant recent advances have involved a new capability to eradicate rodents from much larger islands using aerial bait application techniques, and the use of more effective quarantine and contingency procedures to reduce the risks of further invasions. For example, Norway rats (Rattus norvegicus) were recently eradicated from Campbell Island (112 km2), and this has opened the way for important species recovery and restoration programmes. The Department of Conservation is applying a strategy to develop capacity to eradicate different suites of invasive species from further islands and to refine procedures to minimize invasion risks. Important recent progress has also been made in controlling invasive species on the New Zealand "mainland" - sites not surrounded by water, where terrestrial pest invasion rates are higher than on remote islands - through the development of intensively managed, predator-free areas where threatened species can be re-established.

Further Reading

| Disclaimer: This article contains information that was originally published by the Conservation International. Topic editors and authors for the Encyclopedia of Earth have edited its content and added new information. The use of information from the Conservation International should not be construed as support for or endorsement by that organization for any new information added by EoE personnel, or for any editing of the original content. |