NAFTA as a forum for carbon dioxide permit trading

Contents

- 1 Introduction The carbon (NAFTA as a forum for carbon dioxide permit trading) market is one of the world’s fastest growing markets, with trade volume increasing from 94 million metric tons in 2004 to 800 million metric tons in 2005 at an approximate value of €9.4 billion[1]. A 2003 study identified more than 45 greenhouse gas (GHG) trading systems worldwide in operation or under development, including systems at the sub-national, national, and transnational levels involving both the public and private sectors[2]. This reflects a general trend toward multilevel governance on the issue of climate change, which in turn raises questions about what level of social organization is most appropriate for particular governance tasks.

- 2 The CEC and Emissions Training

- 3 The Institutional Context

- 4 Design Issues

- 5 Overlap with other CO2 Trading Programs

- 6 Electricity Generation Center

Introduction The carbon (NAFTA as a forum for carbon dioxide permit trading) market is one of the world’s fastest growing markets, with trade volume increasing from 94 million metric tons in 2004 to 800 million metric tons in 2005 at an approximate value of €9.4 billion[1]. A 2003 study identified more than 45 greenhouse gas (GHG) trading systems worldwide in operation or under development, including systems at the sub-national, national, and transnational levels involving both the public and private sectors[2]. This reflects a general trend toward multilevel governance on the issue of climate change, which in turn raises questions about what level of social organization is most appropriate for particular governance tasks.

This paper evaluates a proposal to establish a North American emissions trading system within the NAFTA regime. There has been some discussion within the North American Commission for Environmental Cooperation (CEC), NAFTA’s environmental organ, about establishing a CO2 permit trading system to mitigate the environmental impacts of electricity generation. North America consumes half of all electricity produced and consumed in the industrialized world, and electricity generation is a significant source of CO2 emissions in Canada, the U.S., and Mexico. Following a brief introduction to the CEC discussions, this paper addresses three sets of issues related to establishing a NAFTA-wide CO2 permit trading system in the CEC, with particular focus on its implications for climate protection: the institutional context, design elements, and overlap with other trading systems. In the final section, I question the wisdom of establishing a CO2 permit trading system within the NAFTA regime to address the problem of climate change.

The CEC and Emissions Training

The CEC is the primary mechanism for addressing environmental concerns within the NAFTA regime. It was created by the North American Agreement on Environmental Cooperation (NAAEC), a side agreement negotiated at the time the NAFTA regime was created in order to appease environmental groups concerned about the ecological impacts of increased trade in North America. The NAAEC, and its related institutions, seek to manage the economic growth associated with trade liberalization in an environmentally sustainable way; it also allows for action on the environment beyond trade. CEC discussions related to mitigating CO2 emissions are in their infancy, and it is important to acknowledge that climate change is by no means at the top of the CEC agenda. While climate change has been addressed directly on a limited basis, climate-related issues have been taken up in several CEC program areas. The CEC Council (consisting of environment ministers from each Member State) has passed two climate-related resolutions calling for coordination of methodologies for GHG emissions inventories and forecast.

The most recent discussions on climate change are linked to concerns about the environmental impacts, especially related to air quality, of an increasingly integrated North American electricity market. Of course, discussions of air quality and the electricity sector are not divorced from the problem of climate change since electricity generation is a significant (and growing) source of GHG emissions in each NAFTA Member State, accounting for 39 percent of all CO2 emissions in the U.S., 22 percent in Canada and 30 percent in Mexico. The North American electricity market has experienced rapid change over the past decade in the form of increased trade and rising demand, largely due to the general trend of trade liberalization and regional convergence in competitiveness and trade policy. Market integration is likely to continue and generation capacity is expected to increase to meet rising demand. Ultimately, a number of factors will determine the implication of market integration and increased generation capacity on North American GHG emissions, including location, fuel choice, price, infrastructure, market access, grid access, and regulations.

In 2000, the CEC launched an initiative to address the challenge of ensuring “an affordable and abundant supply of electricity without compromising environmental and health objectives”. Specifically, the CEC examined the environmental aspects of the regional electricity market and prospects for green electricity[3]. In the final report, “Environmental Challenges and Opportunities of the Evolving North American Electricity Market,” the initiative’s advisory board made four recommendations specific to climate change and emissions trading:

- Develop a regional GHG emissions inventory;

- Establish a framework for a regional GHG emissions trading regime;

- Develop programs to stimulate investment in clean and renewable energy production (especially in the United States).

In 2002, the CEC Council agreed to include some items from the electricity report in the 2003 CEC Air Quality Work Plan, including comparative studies of North American air quality management standards, regulation and planning, compatibility of standards for construction and operation of electricity generation facilities, and opportunities for emissions trading. In 2004, the CEC issued a report detailing 2002 sulfur dioxide (SO2), nitric oxides (NOx), mercury and CO2 emissions from North American power plants as a result of a 2001 Council Resolution and the “Environmental Challenges” report.

The following sections address three sets of issues related to the development of a CEC-based CO2 permit trading system: the institutional context, design elements, and overlap with other trading systems.

The Institutional Context

Reaching a political agreement to control emissions is a key factor in the success of any emissions trading system. This section considers the ability of the CEC to facilitate agreement among its Member States to control CO2 emissions. I examine the specific rules and structures of the CEC and the broader NAFTA regime, and conclude that reaching political agreement on controlling CO2 emissions depends on linking CO2 to broader air quality and energy concerns rather than climate change. Moreover, political agreement must rest on a core commitment to NAFTA’s trade liberalization objective.

The CEC

The CEC’s capacity to facilitate political agreement on controlling CO2 emissions is constrained by the absence of common interests on climate change. NAFTA Member States have distinct domestic approaches to climate change, which have developed independently of one another. Moreover, Canada, the United States and Mexico have different levels of economic development, which has also shaped their respective responses to climate change. The United States focuses on reducing the carbon intensity of its economy through voluntary programs. The Canadian system consists of government regulations, including a domestic emissions trading system, and strategic investment designed to achieve its Kyoto target and to become a world leader in developing clean technology. Mexican climate policy has focused on developing an emissions inventory, mitigation projects in the forestry and energy sectors, and attracting investment through the Clean Development Mechanism and Joint Implementation program under the Kyoto Protocol. Canada and Mexico are both parties to the Kyoto Protocol (the United States rejected the Kyoto Protocol in March 2001), although only Canada has a binding international commitment to reduce its GHG emissions. The CEC, as an intergovernmental body, has no authority to promote policy coordination unless Member States concede the necessity of doing so, which seems unlikely given the different national approaches to climate change and resistance on the part of the United States.

In contrast, NAFTA Member States do appear to have common interests related to air quality and energy supply as reflected in the CEC’s programs and projects. The Environment, Economy, and Trade Program seeks to understand the relationship between [[trade] and the environment], encourage trade in environmental goods and services, and partner with financial institutions on issues of finance and the environment. This program includes projects on renewable energy in the context of greening trade, green procurement programs, and identifying the environmental implications of the North American electricity market. The aim of the Pollutants and Health Program is “to establish cooperative initiatives on a North American scale to prevent or correct the adverse effects of pollution on human and ecosystem health”. One project under this program aims to facilitate coordination among air quality management agencies in North America.

In this context, the CEC may be able to facilitate political agreement on controlling CO2 emissions to the extent that CO2 is linked to air quality and energy issues rather than climate change. Regional organizations, which typically address many issues simultaneously, can promote the development of shared interests by linking a particular issue to other issues addressed within the organization that may be of greater concern to one or more Member States. Indeed, we see this sort of issue linkage in the CEC where CO2 is often treated like other air pollutants produced by utilities.

NAFTA

Another important component of the institutional context concerns the relationship between a CEC-based CO2 permit trading system and the broader NAFTA regime, where trade liberalization is the primary objective. Consistent with the NAFTA treaty, the CEC rests upon a core set of neoliberal economic assumptions—trade will increase prosperity, environmental protection is an important part of prosperity, and trade will create greater resources for environmental protection—and works to promote environmental sustainability in ways that are consistent with NAFTA’s goal of trade liberalization. On the general relationship between the environment and trade in the NAFTA context, Stevis and Mumme contend the environment plays a secondary role. It is therefore not surprising that emissions trading has emerged as a preferred policy option within the CEC for mitigating the environmental impacts of electricity generation since market-based instruments such as emissions trading are seen to offer a win-win solution to environmental problems by providing economic incentives and flexibility.

At the same time, the fact that a CEC-based CO2 permit trading system would be nested within the broader NAFTA regime means that it would need to be consistent with NAFTA’s trading rules in general and rules specific to the electricity sector in particular. Russell identifies a number of potential conflicts between a NAFTA-wide emissions-trading system and trade and investment provisions in the NAFTA treaty. For example, would tradable emissions units (TEUs) be treated goods and therefore subject to Chapter 3 provisions on national treatment and market access? Would purchasing TEUs from entities in other countries fall under Chapter 11 rules regarding investment? Emissions allowance units could be considered as subsidies subject to extra duty when transferred between countries. Is trade in TEUs an activity linked to the procurement of energy goods and services? Finally, could activities involved in the trading system be viewed as trade restrictions? These issues must be given careful consideration in any future discussions of a CEC-based trading system.

Design Issues

Framing the problem of CO2 emissions as an issue of air quality and energy has implications for the design of a CEC-based permit trading system. The design of an emissions trading system affects its environmental integrity and economic efficiency. This section analyzes key design elements involving coverage (gases and sectors) and targets (caps and allocation), and identifies issues that may arise in the context of designing a CEC-based CO2 permit trading system. I find several instances in which the goals of environmental integrity and economic efficiency are likely to come into conflict. Given NAFTA’s focus on trade liberalization, the CEC may be likely to resolve such conflicts by giving priority to economic efficiency. I also argue that some design choices could render a CEC-based CO2 permit trading system meaningless for climate change.

Coverage

Trading systems that include a variety of gases give participating installations the flexibility to reduce emissions where costs are lowest. Roughly half of all CO2 permit trading systems include a basket of six [[GHG]s], which makes sense in addressing the problem of climate change since each has a warming potential. At the same time, monitoring and verifying emissions reductions for several gases can be difficult, so many systems such as the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI) only include CO2. A CEC-based trading system would likely include only CO2 since CO2 is the only GHG that has been monitored to date on a cross-national basis. In addition, reaching agreement among Member States to include a broader range of GHGs could be difficult given that the CEC views CO2 as an air pollutant rather than a contributor to climate change.

Of course, this framing also makes it likely that a CEC-based system would include other air pollutants that are monitored cross-nationally, such as sulfur dioxide (SO2), nitric oxides (NOx) and mercury. As noted above, including several gases is economically desirable because facilities can choose to reduce emissions of gases where the costs are lowest. However, by including non-GHGs, a CEC-based system may have little impact on the problem of climate change if participating facilities routinely choose to reduce SO2, NOx or mercury emissions rather than CO2. One way to achieve environmental integrity in terms of climate protection is to set emissions caps on a gas-by-gas basis. However, this would reduce the flexibility that comes with multi-gas coverage, potentially raising compliance costs.

Ideally, a CO2 permit trading system should have broad participation from a variety of sectors and emissions sources, since sources are highly diffuse across the economy and broad participation allows for greater opportunity to identify low-cost reduction options. At the same time, broad participation may be administratively or politically prohibitive. The vast majority of CO2 permit trading systems focus on large final emitters (e.g. power plants), which tends to keep the number of facilities at a manageable level while also covering a relatively high percentage of emissions. Discussions within the CEC have focused on the electricity generation sector. This seems to be an appropriate compromise given its central role in producing CO2 emissions as well as other air pollutants. Another related issue is whether participation should be mandatory among facilities in the covered sectors. Participation in a CEC-based trading system would likely be voluntary given the Bush administration’s opposition to regulating CO2 emissions at U.S. facilities. Ausili et al. argue that allowing facilities to voluntarily join a trading system creates a problem of “adverse selection” whereby only those firms whose emissions are likely to decrease anyway join in thereby reducing the demand for (and thus price of) credits.

Many allowance trading systems let credits purchased from project offsets be included. Allowing offset credits is one way of encouraging participation in trading schemes by developing countries since they are likely to attract investment in offset projects. In North America, allowing project credits to some extent could be a particularly attractive option for Mexico whose domestic focus has been on situating itself to provide this service under the Kyoto Protocol. However, the problem with offset credits is that they fall outside the emissions cap and can thus lead to greater emissions, thereby jeopardizing the environmental integrity of the trading system.

Targets

Two key tasks in setting up a permit trading system are setting the cap, or the upper limit on emissions of covered gases, and allocating emissions allowance among facilities in the selected sector(s). Caps can be expressed in a variety of ways: absolute tons of emissions, percentage of emissions from a base year, or intensity-based emissions standards. In systems that include a number of gases, targets may reflect an overall cap on the emissions of all gases combined or they can be set on a gas-by-gas basis. As mentioned above, if a CEC-based CO2 permit trading system is to be climate-relevant, it must have a gas-by-gas cap. However, setting a CO2 cap in the North American context is likely to be difficult as there is no clear basis for doing so. NAFTA Member States have very different domestic approaches to climate change, and only Canada has a binding target to reduce emissions under the Kyoto Protocol. As discussed above, the CEC has limited authority over its Member States and is thus unable to impose targets without the consent of Member States. Moreover, the scientific rational for setting a CO2 target linked to air quality is weak.

Once a target is set, emissions allowances must be allocated among participating facilities, which can be done by a central authority (e.g., the CEC) or by jurisdictions within the trading system (e.g., national governments) thereby enhancing flexibility. The latter option is most likely in the North American context given the CEC’s weak authority over Member States. Each jurisdiction could then decide how to allocate allowances. Under grandfathering, allowances are distributed to participating facilities based on historical emissions and/or production levels. Alternatively, facilities can be required to purchase allowances through an auction. Auctioning allowances is seen to be more economically efficient and can be useful for early price recovery. At the same time, auctioning can be politically contentious. in the initial stages, grandfathering is less likely to mobilize opposition from covered facilities and may enhance prospects of getting a system up and running. However, a potential weakness of the grandfathering approach recently became apparent when carbon credits within the European system lost 50 percent of their value. Several EU countries announced that their 2005 emissions were smaller than expected, which in turn reduced future demand for credits. According to The Economist (May 6, 2006), this reflects “industry’s success in getting itself allocated more permits than actual emissions warranted when the scheme was launched.”

Overlap with other CO2 Trading Programs

The design of a CEC-based trading system also has implications for overlap with other CO2 permit trading systems. In recent years, CO2 permit trading systems have emerged at a variety of levels of social organization in both the public and private spheres, reflecting a general trend toward multi-level governance on the issue of climate change. In a situation of multi-level governance, governance arrangements may overlap both horizontally (across space) and vertically (across levels of social organization), and synergies between overlapping institutions cannot be assured. Young highlights the need to “ensure that cross-scale interactions produce complementary rather than conflicting actions.” This section considers overlap between a CEC-based CO2 permit trading system and seven allowance trading systems in operation, under development, or proposed in North America and Europe as of February 1, 2006 (see Table 1)[4]. I identify two areas of potential conflict: regulation of electricity generation and the ability of Canada to meet is commitment under the Kyoto Protocol.

| Table 1: GHG Allowance Trading Systems in North America and Europe | ||

| Trading System | Status | Description |

| Canadian Large Final Emitters (LFEs) |

To start in 2008 | Part of Canadian government’s comprehensive planning for honoring its Kyoto Commitment. Sets CO2 reduction targets for 700 companies accounting for nearly 50 percent of Canada’s emissions |

| Chicago Climate Exchange | Operational (pilot phase 2003-2006) |

Voluntary trading program for companies, municipalities and universities in Canada, the United States and Mexico. |

| EU Emissions Trading System (ETS) |

Operational (as of 1 January 2005) |

Part of Kyoto compliance system; includes CO2 emissions from more than 12,000 installations in the energy and industrial sectors |

| New England Governors/ Eastern Canadian Premiers (NEG/ECP) |

Proposed in 2001 | Part of NEG/ECP climate change program to reduce GHG emissions to 1990 levels by 2010 and 10 percent below by 2020. Exploring options for cross-border emissions trading, perhaps through RGGI. |

| New Hampshire | Operational (begun in 2002) |

Mandatory caps on CO2, SO2, NOx and mercury emissions for state’s power plants. Trading allowed in order to meet CO2, SO2 and NOx targets. |

| Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI) |

Planned (proposed in 2003) |

Establish a common CO2 permits trading system from Maryland to Maine covering power plants. |

| U.S. Climate Stewardship Act | Legislation introduced the Senate in 2005 |

Proposal to require all entities emitting more than 10,000 tons of CO2 equivalent a year in the electricity, transportation, industry and commercial sectors to stabilize emissions at 2000 levels over 2010-2015 period. Could use trading to meet target. |

| Sources: Chicago Climate Exchange, 2004; Government of Canada, 2005; New England Governors/Eastern Canadian Premiers, 2001; Pew Center on Global Climate Change, 2006; RGGI, 2005; Selin and VanDeveer, 200 | ||

Electricity Generation Center

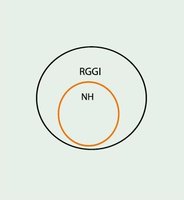

Figure 1. Overlap of RGGI and New Hampshire trading systems. (Source: Canada Institute)

Figure 1. Overlap of RGGI and New Hampshire trading systems. (Source: Canada Institute)  Overlap of CEC and North American trading systems. (Source: Canada Institute)

Overlap of CEC and North American trading systems. (Source: Canada Institute) CO2 permit trading systems in North America and Europe vary in terms of the economic sectors covered and whether participation by entities within those sectors is mandatory or voluntary (Table 2). Despite this variation, it is notable that the electricity sector is subject to regulation in the Canadian, EU ETS, New Hampshire, RGGI and Climate Stewardship Act systems and is the likely target of a CEC-based emissions trading system. In the case of the New Hampshire and RGGI systems, the overlap produces complementarity because the RGGI is explicitly designed to help states meet their specific goals (Figure 1). However, overlap between these systems and a CEC-based trading system could result in conflict if power generation facilities in Canada and the United States find themselves subject to conflicting regulations (Figure 2).

When overlapping institutions come into conflict, there may be incentives for actors to shift political authority to the venue most likely to promote a favorable policy. Owners of North American power-generation facilities may prefer to shift primary authority to a CEC-based system for two reasons. First, the CEC jurisdiction would cover all power plants in North America, which would lessen the risk that some facilities may gain a competitive advantage because they face no or less restrictive regulations. Second, it is possible that a CEC-based program rationalized in terms of air quality would set a less stringent CO2 reduction target than the other systems, which are justified in terms of mitigating the threat of climate change.

Canada and the Kyoto Protocol

It is also important to consider potential overlap between a CEC-based trading system and the international climate change regime. Analyses of the global carbon market frequently distinguish between Kyoto and non-Kyoto systems, based on the system’s linkages to the Kyoto Protocol. The Canadian LFE and EU ETS systems are clearly nested within the Kyoto system; they are designed to facilitate compliance with Kyoto emissions reduction commitments. Two other systems in North America interact with the international climate change regime as well. The NEG/ECP Climate Change Action Plan 2001 identifies as its long-term goal the need to “reduce regional GHG emissions sufficiently to eliminate any dangerous threat to the climate” and notes that this goal “mirrors that of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC)”. The U.S. Climate Stewardship Act acknowledges the United States’ obligation, as a party to the UNFCCC, to stabilize its GHG emissions at 1990 levels (although it establishes an alternative target date).

| Table 2: Participation in Emission Trading Systems | |

| System | Participation |

| Canadian LFEs | Mandatory participation for large final emitters in the mining and manufacturing, oil and gas, and thermal electricity sectors |

| Chicago Climate Exchange | Voluntary participation for corporations, municipalities, universities, and non-profit organizations |

| EU ETS | Mandatory participation for combustion plants; oil refineries; coke ovens; iron and steel plants; cement, glass, lime, brick and ceramics factories; and pulp and paper. |

| NEG/ECP | No data |

| New Hampshire | New Hampshire Mandatory participation for fossil-fuel fired power plants |

| RGGI | Voluntary* participation for power generation facilities |

| Climate Stewardship Act | Mandatory participation for electricity, transportation, industry and commercial sectors |

| *Depends on the situation within a member state, which can require mandatory participation. | |

A CEC-based trading system is difficult to classify according to the Kyoto/non-Kyoto distinction. One the one hand, a CEC-based emissions trading system would not be driven by compliance with the Kyoto Protocol since not all of its Member States have Kyoto targets, and it is rationalized more broadly in terms of air quality and energy issues. On the other hand, Canada does have an obligation to reduce its GHG emissions six percent below 1990 levels under the Kyoto Protocol. Due to market forces in North America, Canadian firms have become major suppliers of oil and natural gas to the Unites States, leading to increased emissions and higher Kyoto compliance costs. This puts Canada in a difficult situation. The EU ETS, as the model for the Kyoto trading system, can be linked to systems in countries that have ratified the Kyoto Protocol through mutual recognition of allowances. However, under these rules, credits obtained from U.S. firms (located in a non-Party state) would not be recognized internationally and thus could not be used to meet Canada’s Kyoto commitment. In other words, institutional interplay between a CEC-based trading system and the international climate change regime leads to a conflict that could undermine Canada’s ability to comply with its Kyoto target.

Conclusion

This paper has examined several issues related to a proposal to establish a NAFTA-wide CO2 permit trading system within the CEC. I find that the political foundation for such a system depends on framing CO2 as an issue related to air quality and energy rather than climate change and relying on policies that do not threaten the goal of trade liberalization. In addition, the design of such a system will give rise to conflicts between economic efficiency and environmental integrity, with economic efficiency likely to prevail given NAFTA’s trade liberalization goal. Finally, I contend that overlap between a CEC-based CO2 permit trading system and other trading systems in North America and Europe could result in conflicts over the regulation of the electricity generation sector and with the international climate change regime.

As noted in the introduction, emissions trading illustrates the increasingly multilevel nature of climate governance. In systems of multilevel governance it is important to allocate governance tasks to the most appropriate level(s) of social organization. In North America, I find little value-added in establishing a CO2 permit trading system at the regional (inter-state, continental scale) level as a strategy for addressing climate change. Because of its intergovernmental nature, the CEC is unable to promote harmonization of climate policy among Member States without their consent. Instead, it must address climate change indirectly by linking the problem to broader issues of air quality and energy. While this may be a politically useful strategy, it could dilute the impact of the trading system on climate change if CO2 emissions are not considered separately from other air pollutants. In addition, the fact that the CEC is nested within the broader NAFTA regime means that conflicts between environmental integrity and economic efficiency are likely to be resolved in favor of economic efficiency so as to be consistent with the goal of trade liberalization. Finally there is danger that a CEC-based CO2 permit trading system could undermine the effectiveness of trading systems at other levels of social organization.

This is not to say that NAFTA has no role in governing climate change. As cross-border, climate-related activities intensify, NAFTA institutions are likely to face greater pressure to address climate change in the future. The ongoing challenge will be to identify appropriate tasks that will not undermine efforts to mitigate GHG emissions in other spheres and tiers of governance.

Image by NASA (Public Domain Image)

Image by NASA (Public Domain Image)

Notes (NAFTA as a forum for carbon dioxide permit trading)

Further Reading

- Alter, Karen J. and Sophie Meunier. 2006. “Nested and Overlapping Regimes in the Transatlantic Banana Trade Dispute.” Journal of European Public Policy, 13(3):362-382.

- Aulisi, Andrew, Alexander F. Farrell, Jonathan Pershing and Stacy D. VanDeveer. 2005. Greenhouse Gas Emissions Trading in U.S. States: Observations and Lessons from the OTC NOx Budget Program, WRI White Paper. Washington, DC: World Resources Institute.

- Axelrod, Robert and Robert O. Keohane. 1986. “Achieving Cooperation Under Anarchy: Strategies and Institutions.” In Cooperation Under Anarchy, edited by K. A. Oye, 226-254. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN: 0691022402

- Berkes, Fikret. 2002. “Cross-scale Institutional Linkages: Perspectives from the Bottom Up.” In The Drama of the Commons, edited by E. Ostrom, T. Dietz, N. Dolsak, P. C. Stern, S. Stonich and E. U. Weber, 293-321. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press. ISBN: 0309082501

- Betsill, Michele M. and Harriet Bulkeley. 2006. “Cities and the Multilevel Governance of Global Climate Change.” Global Governance, 12(2):141-159.

- Betsill, Michele M. Forthcoming. “Regional Governance of Global Climate Change: The North American Commission for Environmental Cooperation.” Global Environmental Politics.

- CEC. 1995. Statement of Intent to Cooperate on Climate Change and Joint Implementation. Montreal: Commission for Environmental Cooperation.

- CEC. 2001. Council Resolution: 01-05. Promoting Comparability of Air Emissions Inventories. Montreal: Commission for Environmental Cooperation.

- CEC. 2002. Environmental Challenges and Opportunities of the Evolving North American Electricity Market: Secretariat Report to the Council under Article 13 of the North American Agreement on Environmental Cooperation. Montreal: North American Commission for Environmental Cooperation.

- CEC. 2005. Our Programs and Projects. Montreal: North American Commission for Environmental Cooperation.

- Charnovitz, Steve. 2003. “Trade and Climate: Potential Conflicts and Synergies.” In Beyond Kyoto: Advancing the International Effort Against Climate Change, 141-170. Arlington, Va.: Pew Center on Global Climate Change.

- Christiansen, Atle C. and Jørgen Wettestad. 2003. “The EU as a frontrunner on greenhouse gas emissions trading: how did it happen and will the EU succeed?” Climate Policy, 3(1):3-18.

- Dukert, Joseph M. 2002. A Review: Environmental Challenges and Opportunities of the North American Electricity Market. Paper presented at a symposium organized by the Commission on Environmental Cooperation in North America, Background Paper 7, June.

- European Commission. 2004. EU Emissions Trading: An Open Scheme Promoting Global Innovation to Combat Climate Change. Brussels: European Commission.

- Ferretti, Janine. 2002. “NAFTA and the Environment: An Update.” Canada-United States Law Journal, 28:81-89.

- Gerber, Elisabeth R. and Ken Kollman. 2004. “Authority Migration: Defining an Emerging Research Agenda.” PS: Political Science and Politics, 37(3):397-410.

- Government of Canada. 2005. Moving Forward on Climate Change: A Plan for Honouring our Kyoto Commitment. Ottawa: Government of Canada.

- Hasselknippe, Henrik. 2003. “Systems for Carbon Trading: An Overview.” Climate Policy, 3(2):43-57.

- Hasselknippe, Henrik and Kjetil Røine. 2006. Carbon 2006: Towards a Truly Global Market (28 February 2006). Oslo: Point Carbon.

- Horlick, Gary, Christiane Schuchhardt, and Howard Mann. 2002. NAFTA Provisions and the Electricity Sector (June), Environmental Challenges and Opportunities of the Evolving North American Electricity Market, Background Paper 4.

- Instituto Nacional de Ecología. 2001. México: Segundo Comunicación Nacional ante la Convención Marco de las Naciones Unidas sobre el Cambio Climático. D.F. México: Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales, Instituto Nacional de Ecología.

- JPAC (Joint Public Advisory Committee). 2003. Discussion Questions on CEC Air Quality Work Plan: Assessments of Transboundary Air Issues Under the 2002 CEC Council Final Communique. Montreal: CEC.

- Lecocq, Frank and Karan Capoor. 2005. State and Trends of the Carbon Market 2005 (16 May). Geneva: International Emissions Trading Association.

- Levy, Marc, Robert O. Keohane and Peter M. Haas. 1995. “Improving the Effectiveness of International Environmental Institutions.” In Institutions for the Earth: Sources of Effective International Environmental Protection, edited by P. M. Haas, R. O. Keohane and M. Levy, 397-426. Cambridge: MIT Press. ISBN: 0262581191

- Miller, Paul J. and Chris Van Atten. 2004. North American Power Plant Air Emissions. Montreal: North American Commission for Environmental Cooperation.

- McKinney, Joseph A. 2000. Created from NAFTA: The Structure, Function and Significance of the Treaty’s Related Institutions. Armonk, N.Y.: M.E. Sharpe. ISBN: 0765604663

- Mumme, Stephen P. and Donna Lybecker. 2002. “North American Free Trade Association and the Environment.” In Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems. Oxford, U.K.: EOLSS Publishers.

- New England Governors/Eastern Canadian Premiers. 2001. Climate Change Action Plan 2001 (August).

- Page, Robert. 2002. Kyoto and Emissions Trading: Challenges for the NAFTA Family. Canada-United States Law Journal, 29:55-66.

- Selin, Henrik and Stacy D. VanDeveer. 2005. “Canadian-U.S. Environmental Cooperation: Climate Change Networks and Regional Action.” American Review of Canadian Studies, (Summer):353-378.

- Stevis, Dimitris and Stephen P. Mumme. 2000. “Rules and Politics in International Integration: Environmental Regulation in NAFTA and the EU.” Environmental Politics, 9(4):20-42.

- U.S. Department of State. 2002. U.S. Climate Action Report: 2002. Third National Communication of the U.S. under the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of State.

- Young, Oran R. 2002. “Institutional Interplay: The Environmental Consqeuences of Cross-Scale Interactions.” In The Drama of the Commons, edited by E. Ostrom, T. Dietz, N. Dolsak, P. C. Stern, S. Stonich and E. U. Weber, 263-291. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press. ISBN: 0309082501

- Zhang, Zhong Xiang. 2003. Open Trade with the U.S. without Compromising Canada’s Ability to Comply with its Kyoto Target. Paper read at Second North American Symposium on Assessing the Environmental Effects of Trade.

Citation

(2012). NAFTA as a forum for carbon dioxide permit trading. Retrieved from http://editors.eol.org/eoearth/wiki/NAFTA_as_a_forum_for_carbon_dioxide_permit_trading- ↑ In April 2006, the value of carbon credits within the European Emissions Trading Scheme decreased by half. The long-term implications of this for the global carbon market are unclear (The Economist, May 6, 2006).

- ↑ Trading systems are typically categorized as either allowance or credit systems. Allowance trading system (also referred to as “cap and trade” or permit systems) involve setting an upper limit on emissions levels, distributing emissions allowances among participants in the system and letting participants trade allowances among themselves in order to meet their respective commitments. Credit (or project-based) trading systems engage in the purchase and transfer of emissions credits derived from specific projects. The permit trading system discussed in this paper is an example of an allowance trading system.

- ↑ The process was overseen by an advisory board and involved the production of several working papers and three public events. Copies of these papers and information on the public events are available here.

- ↑ The analysis draws on a framework developed by Selin and VanDeveer (2003) to analyze governance linkages, which consist of “structural connections between components of particular international institutions.” I rely on data from primary and secondary documents for each trading system as well as databases compiled by the International Emissions Trading Association and the Pew Center on Climate Change.

1 Comment

Sean Tracy wrote: 05-18-2011 06:25:58

There are several NGOs working on creating localized GHG inventories (Sierra Club Cool Cities Campaign for example). The CEC could tap into these established networks to collect more data. http://www.coolcities.us/