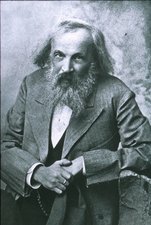

Mendeleev, Dimitri Ivanovich

| Topics: |

Dmitri Ivanovich Mendeleev (1834–1907) was born in Tobolsk, Siberia, where his father taught Russian literature and his mother owned and operated a glassworks. His early contacts with political exiles gave him a lifelong love of liberal causes, and his freedom to roam the glassworks stimulated an interest in business and industrial chemistry. His mother—after her husband's death and shortly before her own—took the 15-year-old Dmitri to St. Petersburg. There he attended the Main Pedagogical Institute and the University of St. Petersburg, where he pursued a doctorate in chemistry. During his graduate studies he traveled to Heidelberg to work with Robert Bunsen.

Mendeleev and Julius Lothar Meyer were among the young chemists attending the Karlsruhe Congress in 1860, and both were impressed with Stanislao Cannizzaro's presentation of Amedeo Avogadro's hypothesis. For both, writing a textbook proved to be the impetus for developing the periodic table—that is, a device to present the more than 60 known elements in an intelligible fashion.

After returning to St. Petersburg from Karlsruhe, Mendeleev taught at the St. Petersburg Technological Institute, completed his doctoral dissertation, started an experimental farm, and lectured for the Free Economic Society on agricultural topics. When in 1867 he was appointed to the chair of chemistry at the University of St. Petersburg, he too began to write a textbook, Osnovy Khimii (Principles of Chemistry; first edition, 1871), and worked out the "periodic law," which was first published in papers in 1869. Mendeleev succeeded in arranging all known elements into one table.

Although his scientific eminence and the usefulness of his advice protected him to a certain degree, Mendeleev's strong democratic leanings got him into trouble with political and academic authorities. But in 1890 he left his professorship at the University of St. Petersburg after an official rebuke for delivering a student protest to the ministry of education. He then rose in government service to the position of Director of the Central Board of Weights and Measures. He contributed to the modernization of Russia through his reports and recommendations on weights and measures, protective tariffs, shipbuilding and shipping routes in Arctic regions, the manufacture of smokeless powder, and the development of heavy industry. When he died, students carried the periodic table in the funeral procession.

Further Reading