Manovo-Gounda-St Floris National Park, Central African Republic

| Topics: |

Manovo-Gounda-St Floris National Park (8° 05'-9° 50'N, 20° 28'-22° 22'E) is a World Heritage Site. The importance of this park is in its wealth of flora and fauna. Its vast savannas shelter a wide variety of species: black rhinoceros, elephant, cheetah, leopard, wild dog, red-fronted gazelle and buffalo; a wide range of waterfowl species also occurs in the northern floodplains.

Contents

- 1 Threats to Site

- 2 Geographical Location

- 3 Date and History of Establishment

- 4 Area

- 5 Land Tenure

- 6 Altitude

- 7 Physical Features

- 8 Climate

- 9 Vegetation

- 10 Fauna

- 11 Local Human Population

- 12 Visitors and Visitor Facilities

- 13 Scientific Research and Facilities

- 14 Conservation Value

- 15 Conservation Management

- 16 IUCN Management Category

- 17 Further Reading

Threats to Site

The site was added to the List of World Heritage in Danger following reports of illegal grazing and poaching by heavily armed hunters, who may have harvested as much as 80% of the park's wildlife. The shooting of four members of the park staff in early 1997 and a general state of deteriorating security brought all development projects and tourism to a halt. The government of the Central African Republic proposed to assign site management responsibility to a private foundation. The preparation of a detailed state of conservation report and rehabilitation plan for the site was recommended by the World Heritage Committee at its 1998 session.

Geographical Location

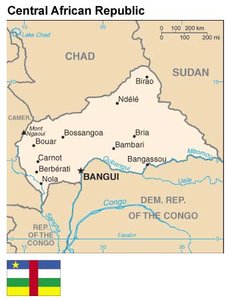

The Park occupies most of the eastern end of Bamingui-Bangoran province in the north of the country. Its boundary on the north is the international border with Chad on the River (Bahr) Aouk and R.Kameur; on the east, the R.Vakaga, on the west the R.Manovo about 40 kilometers (km) east of Ndéle, and in the south the ridge of the Massif des Bongo. The Ndéle-Birao road runs through the park. 8° 05'-9° 50'N, 20° 28'-22° 22'E

Country Flag and Map of the Central African Republic where the Manovo-Counds-St Floris National Park is located (Source: U.S. Department of State)

Country Flag and Map of the Central African Republic where the Manovo-Counds-St Floris National Park is located (Source: U.S. Department of State) Date and History of Establishment

- 1993: Part of the area originally designated Oubangui-Chari National Park (13,500 hectares (ha)), renamed Matoumara National Park in 1935;

- 1940: Renamed St. Floris National Park (40,000 ha);

- 1960: St Floris National Park enlarged to 100,700 ha, and to 277,600 in 1974

- 1979: Manoco-Gounda-St. Floris National Park designated, including St Floris National Park and the former Safarafric hunting/tourism concession

Area

1,740,000 ha. Contiguous on the north to the Réserve de faune de l'Aouk-Aoukalé (330,000 ha), and on the east to the Réserve de faune de l'Ouandjia-Vakaga (130,000 ha). A proposed Réserve de faune du Bahr Oulou lying between these two reserves would also be contiguous, if designated.

Land Tenure

Government property. In 1984 a renewable twenty year agreement between the government and Manovo S.A made that company responsible for managing the park and exploiting its tourist potential.

Altitude

400 meters (m) to 800 m.

Physical Features

The park comprises three main zones: the grassy floodplain of the Bahr Aouk and Bahr Kameur rivers in the north, a gently undulating transitional plain of bushy or wooded savanna with occasional small granite inselbergs, and the Chaine des Bongo plateau in the south. The seasonally flooded lowlands have fine, deep, alluvial soils, where the drainage may be poor. The plain has coarse, well-drained, generally ferruginous and relatively infertile soils. Particularly in depressions, these develop a lateritic pan on which woody vegetation is sparse or absent. The massif is chiefly highly dissected sandstone, rising from the plain in a 100-200 m escarpment. Five major rivers thread through the park from the massif in the south east to the Bahr Aouk - Bahr Kameur floodplain in the north: the Vakaga on the eastern boundary, the Goro, Gounda, Koumbala, and the Manovo on the western boundary. The basins of the three central rivers all lie within the Park. However, their flow may be intermittent near the end of the dry season, and may only reach the Bahr Aouk and Bahr Kameur during the wettest months.

Climate

The climate is tropical, semi-humid Sudano-Guinean, with a mean annual rainfall of between 950 and 1,700 millimeters (mm), mainly falling between June and November, rainfall being much higher in the upland areas. December to May is hot and dry and grass fires are common in the late winter. Temperatures are much higher in the northern floodplain than on the plateau.

Vegetation

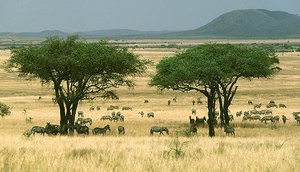

African Savanna which has a tropical climate (Source: Fullerton College)

African Savanna which has a tropical climate (Source: Fullerton College) The park is the largest savanna park in west and central Africa. It covers a broad range of habitat types ranging on a gradient from Sudano-Sahelian grassy savanna on the northern floodplains through bushy savanna, treed savanna and Sudanese wooded savanna, over the undulating land to its south threaded by gallery forest, to Sudano-Guinean savanna-woodland on the plateau in the southeast. Wooded savannas cover 70% of the area.

From riverside swamps the vegetation grades from sandy grassland of perennial grass communities, sedges and annual forbs covering the most heavily flooded areas, to seasonally flooded flat river valleys where the trees and shrubs are confined to patches of higher ground and have to be both flood and fire resistant. Predominant grassland species include perennials such as Vossia cuspidata, Echinochloa stagnina, Jardinea congoensis, Setaria anceps, Hyparrhenia rufa, and Eragrostis sp., their distributions depending on the duration and depth of seasonal flooding. In this impeded drainage tree savanna Pseudocedrela kotschyi and Terminalia macroptera with Combretum glutinosum. grow in soil of varying depths over ironstone. In less wet soils mixed open wooded savanna with a sparse shrub layer carries the same species plus Terminalia laxiflora, Combretum glutinosum and Anogeissus leiocarpus around seasonal streams and isolated low points. All the grassy savannas are heavily used by wildlife, especially ungulate herds. They are interspersed with less common types which form a mosaic related to soil and topography. These include Combretum scrub or ironstone meadow, ringed by stunted vegetation, where the laterite pan is close to the surface, bare isolated inselbergs and termite mounds which can shelter quite dense growth.

Wide stretches of the transitional plains are covered by wooded savanna of Terminalia laxiflora with Crossopteryx febrifuga and Butyrospermum parkii, heavily used by the larger mammals such as elephant, during the dry season. South of this is Isoberlinia doka - Monotes kerstingi woodland with little shrub layer or grass that is less used by animals. A dense dry forest of Anogeissus leiocarpus and Khaya senegalensis grows along the edges of the plains, particularly along the Gounda and Koumbala Rivers, and in small islands within the plains. This forest is under threat: Anogeissus leiocarpus is not fire resistant, which, with low rainfall, may be contributing to its decline. The gallery forests in deep high-banked valleys are attractive to monkeys and birds. In the south, the range of habitats is extended. There are broken rocky areas used by baboons, wooded savanna on the plateau, bamboo open savanna and clear forest with dense understory around the sources of the rivers, used by shyer ungulates.

Fauna

The fauna of the Park reflects its transitional position between east and west Africa, the Sahel and the forested tropics. It contains the richest fauna in the country, including some 57 mammals, which have been well protected in the past. In this it resembles the riches of the east African savannas. Faunal studies include those by Spinage, Buchanan & Schacht, and Barber et al., as well as aerial studies reported by Loevinsohn et al. and Loevinsohn. However, their reports cover mainly the northern area of and around St. Floris.

Several mammal species of particular concern to conservationists occur within the park: black rhinoceros Diceros bicornis (E), now reduced to fewer than ten animals, the small forest elephant Loxodonta africana cyclotis (V), which may number 2,000-3,000 individuals, leopard Panthera pardus, cheetah Acinonyx jubatus (V) and wild dog Lycaon pictus (E). Unfortunately, poaching of black rhinoceros and elephant has been heavy, and has decimated leopard and crocodile. Snares catch other species like lions and hyaenas indiscriminately. Red-fronted gazelle Gazella rufifrons (V) is the only gazelle found in the park, on its northeastern edge.

Baboon (Papio anubis), the most common primate (Source: Smithsonian Institution)

Baboon (Papio anubis), the most common primate (Source: Smithsonian Institution) Within the St. Floris region, the most abundant large mammals seem to be kob Kobus kob, hartebeest Alcelaphus buselaphus and grey duiker Sylvicapra grimmia, with other fairly abundant ungulates including waterbuck Kobus ellipsiprymnus, oribi Ourebia ourebi, topi Damaliscus lunatus, reedbuck Redunca redunca, roan antelope Hippotragus equines and giant eland Taurotragus derbianus; also buffalo Syncerus caffer, warthog Phacochoerus aethiopicus and hippopotamus Hippopotamus amphibius. The most common primate recorded by Barber et al. was baboon Papio anubis, with lower numbers of patas and tantalus monkeys (Cercopithecus patas and C. tantalus), and low numbers of black and white colobus monkeys Colobus guereza in the dry forest. Other conspicuous large mammals include lion Panthera leo, giraffe Giraffa camelopardalis. Less common animals in the area include golden cat Felis aurata, red-flanked duiker Cephalophus rufilatus, yellow-backed duiker C. sylvicultor and aardvark Orycteropus afer. Few nocturnal species have been studied, but serval Felis serval may be common, also lesser bush baby Galago senegalensis. De Brazza's monkey Cercopithecus neglectus, greater white-nosed monkey Cercopithecus nictitans and bush pig Potamochoerus porcus have been discovered here since 1980, and Buchanan has also recorded rock hyrax Procavia ruficeps more than 200 km west of the nearest known population. The Nile crocodile Crocodylus niloticus is quite common.

Some 320 species of birds have been identified, with at least 25 species of raptor including bataleur Terathopius ecaudatus, and African fish eagle Cumcuma vocifer. There are large seasonal populations of marabou stork Leptoptilos crumeniferus and pelicans Pelecanus onocrotalus and P. rufescens. The floodplains of the north of the Park are fairly important for both waterbirds and shorebirds. Shoebill Balaeniceps rex (K) nests there. On the plains, ostrich Struthio camelus seem fairly common, moving to woodland to lay their eggs. Several species of bee-eater and kingfisher are present along the rivers.

Local Human Population

Most of the area has been sparsely inhabited since the beginning of the century having been a no-man's-land between opposing sultanates. However, nomadic cattle herders from the Nyala area of Sudan and from Chad, with between 30-40,000 head, enter the park during the winter as part of their dry season range, in a traditional transhumance. In the past, drought has also driven them there. There is sparse and limited agriculture around the park boundaries.

Visitors and Visitor Facilities

Access to the southern part of the park is relatively easy though there are few facilities for visitors. The infrastructure may be improved if it is agreed between the Government and the concessionaire, Manova S.A. This has responsibility for managing tourism within the park, and hunting in the buffer zones for 20 years from 1984, under an agreement with the government. However, in 1996, tourism stopped because the Park was no longer safe for travelers.

Scientific Research and Facilities

An aerial count of larger mammals in parts of the park was carried out by Loevinsohn for FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO)). and again the next year as part of a larger project to improve management of [[fauna in the north of the country. An ecological survey of the St. Floris National Park was carried out by US Peace Corps biologists in 1977 and 1978. The report of this survey includes both general descriptions and species lists, and makes several recommendations. Further research was carried out in the newly-designated park in 1979 to extend much of the work to cover also the Gounda-Koumbala region. Between 1981 and 1984, Peace Corps biologists studied the ecology of elephants in the center of the park, with special reference to diet, distribution and the impact of poaching. Other activities by the research team included observations on poaching and other illegal activities, a botanical survey, noting rare or previously unidentified in the park species, and monitoring (Environmental monitoring and assessment) rhinoceros activity. A research center is planned at Camp Koumbala.

Conservation Value

The Park is one of the major biogeographic crossroads of central Africa. A remarkable range of north-central African savanna ecosystems shelter the country’s richest variety of animals, including black rhinoceroses, elephants, cheetahs, leopards, wild dogs, red-fronted gazelles and buffaloes, and the northern floodplains harbor several species of waterfowl.

Conservation Management

The park was said in the past to be the best protected area in the country. Over several years, FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO)) worked within the Central African Republic to improve wildlife management. As part of this work, Spinage made a preliminary survey of the St. Floris National Park, producing a number of recommendations for improving its management. Recommendations were also made by a series of subsequent studies. Until 1985, development was supported by the Fonds d'Aide et Coopération. Much investment was made to improve the tourist infrastructure. The tourism concessionaire, Manova S.A. also carried out limited park management such as grading tracks and burning to improve game-viewing, but it is unclear how much this was coordinated with the Park management. Most of the present management effort goes into limiting poaching and preventing grazing within park boundaries. Some army support is provided for anti-poaching work, but this has been sporadic and of short-term value.

In 1988 the EEC and FED started a ten-year project costing US$27million to enhance the integrity of the Park, and access into it, also to aid research and develop staff and facilities. Nevertheless, marauding continued. In 1997, the government of the Central African Republic was to give site responsibility to a private foundation which was trying to raise funds to provide staff and equipment for the park. In 2001 an IUCN mission visited the site to prepare for fund-raising and produce a realistic work plan for the next two years plan for the Park's rehabilitation, and the integration of local communities in participatory management. The government was also encouraged to seek the cooperation of neighboring states in limiting poaching.

Management Constraints

The most significant human impact on the park is the professional poaching of large mammals, particularly rhinoceros and elephant. This is facilitated by a main national route which crosses the park. Some poachers come from within the country but most are from Chad and Sudan, well supplied with automatic weapons since the civil wars in those countries. In 1997 uncontrolled poaching reached emergency levels, with heavily armed groups entering the park, setting up camp, and transporting bushmeat out by camel train. Four park staff were killed, and there was no effective anti-poaching force. 80% of the park's wildlife is said to have been harvested by poachers. The numbers of many animals in the area have fallen sharply. The elephant population decreased by 75% between 1981 and 1984, as few as ten rhinoceros remained by 1988, and the giraffe population has declined. Meanwhile, the staff is extremely short of the manpower and equipment needed to manage so large an area and has few firearms and only one vehicle.

Two other factors cause concern: fire, whether initiated by grazers, poachers, hunters or guards, and grazing. Most illegal grazing occurs during the dry season, with huge numbers of cattle moving from the Nyala region of Sudan and from Chad which compete with the wildlife and can introduce disease. This is also affecting the composition of [[grassland]s], with perennial species giving way under grazing pressure to annuals and herbs.

Staff

The park is currently under the administration of one manager and one assistant with five guards, supplemented on occasions by army personnel for anti-poaching patrols. The concessionaire employs ten people on management oriented tasks.

Budget

Little site-specific information is available. The 1988 EEU/FED grant of US$27million to control poaching and grazing for ten years was to be succeeded in 1997 by funding from a private foundation to continue the work. In 2001 the World Heritage Bureau approved a grant of US$150,000 for an emergency rehabilitation plan.

IUCN Management Category

- II National Park

- Natural World Heritage Site, inscribed in 1988. Natural Criteria ii, iv.

- Listed as World Heritage in Danger in 1997 because of very heavy poaching and insecurity.

Further Reading

- Barber, K., Buchanan, S. & Galbreath, P. (1980). An Ecological Survey of the St Floris National Park, Central African Republic. IPAD, US National Parks Service, Washington D.C.

- Buchanan, S. & Schacht, W. (1979). Ecological investigations in the Manovo-Gounda-St Floris National Park ISBN: B0007AWI2G. Ministre des Eaux, Forêts, Chasses et Pêches, Bangui. CAR

- CAR (1987). Nomination of the Parc National du Manovo-Gounda-St Floris for Inscription on the World Heritage List. Ministre du Tourisme, des Eaux, Forêts, Chasses et Pêches, Bangui. Central African Republic.

- CAR (1992). Sauvegarde de Manovo-Gounda St Floris. Patrimoine Mondial. Report of the Haut Commissaire de la Zone Franche Ecologique to UNESCO.

- Douglas-Hamilton, I., Froment, J., & Doungoubé, G. (1985). Aerial survey of wildlife in the North of the Central African Republic. Report to CNPAF, WWF, IUCN, UNDP and FAO.

- IUCN, (1988). World Heritage Nomination - Technical Evaluation. Report to WWF.

- IUCN/WWF Project 3019. Elephant Research and Management, Central African Republic. Various reports.

- IUCN (1997) State of Conservation of Natural World Heritage Properties. Report prepared for the World Heritage Bureau, 21st session, UNESCO, Paris. 7pp.

- Loevinsohn, M. (1977). Analyse des Résultats de Survol Aérien 1969/70. CAF/72/010 Document de Travail No.7. FAO, Rome.

- Loevinsohn, M.,Spinage, C. & Ndouté, J. (1978). Analyse des Résultats de Survol Aérien 1978. CAF/72/010 Document de Travail No.10. FAO, Rome.

- Pfeffer, P. (1983). Un merveilleux sanctuaire de faune Centrafricain: le parc national Gounda-Manovo-St.Floris. Balafon, 58. Puteaux, France.

- Spinage, C. (1976). Etudes Préliminaires du Parc National de Saint-Floris. CAF/72/010. FAO Rome.

- Spinage, C.(1981). Résumé des Aires de Faune Protégées et Proposées pour être Protégées. CAF/78/006 Document de terrain No.2. FAO, Rome.

- Spinage, C. (1981). Some faunal isolates of the Central African Republic. African Journal of Ecology 19(1-2): 125-132.

- Temporal, J-L. (1985). Rapport Final d'Activités dans le Parc National Manovo-Gounda-St Floris. Rapport du projet. Fonds d'Aide et Coopération.

- UNESCO World Heritage Committee (1997). Report on the 20th Session of the World Heritage Committee, Paris.

- UNESCO World Heritage Committee (1998). Report on the 21st Session of the World Heritage Committee, Paris.

- UNESCO World Heritage Committee (2001). Report on the 24th Session of the World Heritage Committee, Paris.

- UNESCO World Heritage Committee (2002). Report on the 25th Session of the World Heritage Committee, Paris

| Disclaimer: This article is taken wholly from, or contains information that was originally published by, the United Nations Environment Programme-World Conservation Monitoring Centre (UNEP-WCMC). Topic editors and authors for the Encyclopedia of Earth may have edited its content or added new information. The use of information from the United Nations Environment Programme-World Conservation Monitoring Centre (UNEP-WCMC) should not be construed as support for or endorsement by that organization for any new information added by EoE personnel, or for any editing of the original content. |