Improving responses through interlinkages in Africa’s policy

Contents

- 1 Introduction Investing in children, ICT and education increases future opportunities. Here a school supported by a horticulture company provides children with the opportunity to use computers. (Source: R. Giling/Still Pictures) Developing an interlinkages approach to policy responses holds promise for identifying comprehensive solutions and for building synergies between diverse policies, thus maximizing the resources available for implementation. Interlinkages between different scales – temporal and spatial – potentially enhance opportunities for implementation. The successful implementation of many policies is dependant on an interlinkages approach. Increasingly an interlinked approach is evident in policies themselves. In the two decades since Our Common Future was published, governments in Africa have increasingly given policy attention to both green and brown environmental issues. Governments today are equally concerned about brown issues, which include air and water pollution, and solid waste management, and acknowledge the link with green issues. Previously, environmental management in Africa focused on the preservation of wildlife and other natural resources; in many countries, particularly in Eastern and Southern Africa, this policy was directly linked to tourism. Environmental management and policy has evolved considerably since the mid-1980s from a wildlife conservation focus to being more integrated, taking into account social and economic issues. Several policy interventions since the 1992 Earth Summit, from Agenda 21 to the World Summit on Sustainable Development (WSSD) Johannesburg Plan of Implementation to the New Partnership for Africa's Development (NEPAD’s) Environmental Action Plan (NEPAD-EAP) give credence to the need for an integrated approach to environmental problems. Development policies are increasingly following suit. (Improving responses through interlinkages in Africas policy)

- 2 Comprehensive and interlinked policies: the poverty reduction strategy papers

- 3 Opportunities for cost-benefit analysis: the value of environmental impact assessment

- 4 Improving implementation through interlinking policies at different scales: NEPAD-EAP and the MDGs

- 5 Further reading

Introduction Investing in children, ICT and education increases future opportunities. Here a school supported by a horticulture company provides children with the opportunity to use computers. (Source: R. Giling/Still Pictures) Developing an interlinkages approach to policy responses holds promise for identifying comprehensive solutions and for building synergies between diverse policies, thus maximizing the resources available for implementation. Interlinkages between different scales – temporal and spatial – potentially enhance opportunities for implementation. The successful implementation of many policies is dependant on an interlinkages approach. Increasingly an interlinked approach is evident in policies themselves. In the two decades since Our Common Future was published, governments in Africa have increasingly given policy attention to both green and brown environmental issues. Governments today are equally concerned about brown issues, which include air and water pollution, and solid waste management, and acknowledge the link with green issues. Previously, environmental management in Africa focused on the preservation of wildlife and other natural resources; in many countries, particularly in Eastern and Southern Africa, this policy was directly linked to tourism. Environmental management and policy has evolved considerably since the mid-1980s from a wildlife conservation focus to being more integrated, taking into account social and economic issues. Several policy interventions since the 1992 Earth Summit, from Agenda 21 to the World Summit on Sustainable Development (WSSD) Johannesburg Plan of Implementation to the New Partnership for Africa's Development (NEPAD’s) Environmental Action Plan (NEPAD-EAP) give credence to the need for an integrated approach to environmental problems. Development policies are increasingly following suit. (Improving responses through interlinkages in Africas policy)

Comprehensive and interlinked policies: the poverty reduction strategy papers

Policies that are comprehensive and adopt an interlinkages approach provide better opportunities for addressing multiple, related challenges and for developing effective solutions.

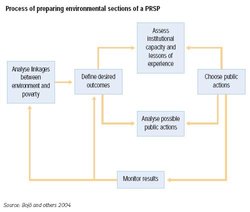

The World Bank’s poverty reduction strategies (PRS) have broken with the narrower economic interventions of the 1980s and 1990s and adopted a more interlinked and comprehensive framework to reducing poverty, that is results orientated. Many countries in Africa have or are developing Poverty Reduction Strategy Papers (PRSPs), as shown in Table 2. In many of these PRSPs, the environment is treated as a key factor because improved environmental conditions, among other results, can help reduce poverty. The reduction of extreme poverty and hunger, and environmental sustainability – both of which are part of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) – are closely linked to the poverty objectives of PRSPs. For PRSPs to be successful they should take into account a comprehensive understanding of poverty in a particular country, choosing the most effective public actions to reduce poverty, and to monitor outcomes and impacts. Figure 1 shows the process of preparing environmental sections of a PRSP.

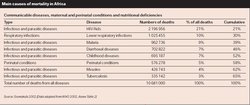

In highlighting the rationale for systematic mainstreaming of environment in PRSPs and associated processes, the World Bank stresses that environmental conditions have major effects on the health, opportunities, and security of poor people. For example, the World Bank reported in 2001 that the burden of disease in sub-Saharan Africa from major environmental risks was 26.5 percent, compared to 18 percent in all least developed countries (LDCs). The environmental risks considered include poor water supply and sanitation, vector diseases (such as malaria), indoor and urban air pollution, and agro-industrial waste. Table 1 shows the main causes of mortality in Africa. Many of these, including respiratory diseases, diarrhoeal diseases and malaria, are caused by environmental factors.

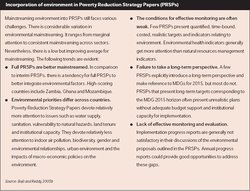

While PRSPs are mainly concerned with addressing poverty, the objectives are also important for achieving sustainable development and, thus, dealing with environmental concerns. The realization of the MDG targets is closely related to reducing and eradicating poverty. Appendix 1 lists the MDG targets and shows progress towards achieving these. However, the extent to which these considerations have been included in country PRSPs varies considerably. Box 1 identifies some of the major trends and Table 3 evaluates environmental mainstreaming in PRSPs.

A review of PRSPs of some African countries already shows strong interlinkages in, between and across environmental, social and economic issues as shown in Table 2. For example, the Burkina Faso PRSP notes that climatic conditions and low agricultural productivity due to soil and water degradation are major constraints to economic growth, contributing to extreme poverty and severe food insecurity in rural areas. Income from farming and livestock raising is highly dependent on rainfall, which varies considerably from year to year. The PRSP highlights a soil and water conservation programme to break the vicious circle of soil degradation, poverty and food insecurity.

In Mauritania, Kenya and Zambia, the PRSPs express concern about property rights related to natural resources and how this affects poverty. Kenya’s PRSP proposes to implement a land law to create an efficient and equitable system of land ownership. It also notes that the violation of water rights, conflicts and pollution have increased.

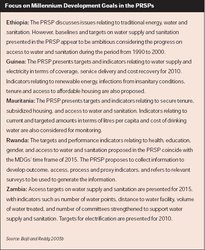

The extent to which the MDGs are specifically addressed also varies. Box 2 gives some examples of African countries that have specifically incorporated the MDGs where these are directly relevant from an environmental perspective.

Opportunities for cost-benefit analysis: the value of environmental impact assessment

The interlinkages approach has the benefit of enabling policymakers to achieve a better grasp of the costs and benefits of their decisions.

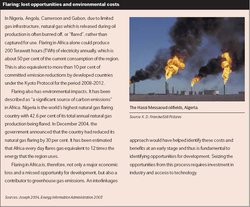

A policy geared towards enhancing utility of the forestry sector by extending commercial logging, for instance, can be very costly to a biodiversity-rich country. For example, in Cameroon – one of the most ecologically diverse countries in Africa – intensive logging threatens the country’s tropical rainforests and the habitat of over 40 species of wildlife, including gorillas, elephants and the black rhinoceros, with extinction. According to research in the late 1990s, the number of logging enterprises increased from 194 to 351 in 1995, following the devaluation of the local currency in 1994. Timber exports grew by 49.6 percent between 1995-96 and 1996-97.

The oil industry is another high-profile issue in which interlinkages between the environment and social and economic development are important. The benefits and costs associated with the industry are often contested. Although the oil industry has been linked to high levels of growth through increasing national income and employment, it can also be a cost on the environment, impacting negatively on coastal and marine environments and tourism, leading to long-term loss of jobs and thus slowing economic growth. In the Niger Delta region of Nigeria, Sub-Saharan Africa's (SSA) largest oil producer, oil extraction has caused severe environmental degradation due to oil spills and lax environmental regulations. Inadequate investment, social and governance policies have meant that growth has not benefited poor people. For many, oil refineries, wells and transportation activities are opportunities to increase and diversify trade relationships with other nations and to participate in the global economy. There is often controversy around oil extraction activities. For example, the US$3,700 million Chad-Cameroon Pipeline Project, which was approved by the World Bank in June 2000, has been the target of protests from environmental and human rights groups. They argue that the project would dislocate inhabitants along the pipeline route and harm wildlife in the rainforests through which the pipeline would pass. Oil pollution is a major issue in Africa with the chronic release of oil in ports through ship leakage, ship maintenance or mishandling. According to the US Energy Information Administration, the problem of oil discharge in ports is often ignored, even though cumulatively the oil may negatively impact the surrounding ecosystem, including seabeds, wetlands and mudlands, which are environmental resources of economic significance.

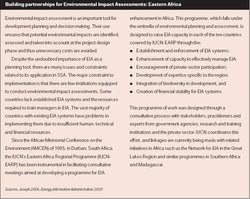

Various tools and policy-making processes seek to address the complex human-environment nexus and use interlinkages to do so. These include integrative assessment processes (discussed in Genetically Modified Crops in Africa) and inclusive policy processes (discussed The Human Dimension and Genetically Modified Crops in Africa). Environmental impact assessments (EIAs) are important tools which employ an integrated and interlinked approach to evaluating relative costs and benefits in diverse spheres – demonstrating the interlinkages between environmental, social and economic issues – and creating opportunities for deciding on appropriate development opportunities. They seek to produce early and adequate information about the likely environmental consequences of certain plans and projects, to propose alternatives and to establish measures to mitigate harm. Additionally, EIAs potentially bring a multiplicity of government agencies and institutions, organizations, experts and members of the public into the decision-making process. The need for an interlinkages approach is further demonstrated in Box 12, which considers the loss of energy in the oil production process that could be used to produce electricity. This lost opportunity is the result of a poorly developed natural gas industry. An interlinkages approach, such as through an EIA, would have helped identify these costs and benefits at an early stage and is, therefore, fundamental to identifying opportunities for development.

National oil industry practices, such as those raised above, may have a bearing on the implementation of several policy instruments, including MEAs such as the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands (Ramsar) and the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), global targets such as the MDGs, and regional plans and programmes such as the NEPADEAP, as well as African regional conventions. Box 3 shows that local activities have impacts that may be felt at different scales. Thus, in developing responses to situations like that described in Box 3, it is crucial that the link to global and regional policy instruments be made. Additionally, for Africa to benefit from the oil industry and simultaneously avoid environmental impacts of global significance, capacity needs to be improved. This can be addressed by the global community making good its pledge at the WSSD to invest in industry and sustainable production methods.

Environmental impact assessment tools are more useful in understanding the complexity of the issues at stake than traditional cost-benefit analysis, which sets out to add up in monetary terms the benefits of a public policy and compare them to the costs. There are major challenges in cost-benefit analysis. More often than not it involves comparing aspects that are fundamentally different and whose range of values cannot be reduced to purely monetary terms. The environment has both use and non-use values. Non-use values are particularly hard to quantify in monetary terms. Cost-benefit analysis cannot overcome its fatal flaw: it is completely reliant on the impossible attempt to price the priceless values of life, health, nature and the future.

Despite the value of EIAs as a decision-making tool, the region faces various challenges in fully implementing this approach, particularly the lack of capacity in human, financial and technical areas. Box 4 looks at how IUCN – the World Conservation Union (IUCN) and the governments in Eastern Africa are working together to enhance EIA capacity.

Improving implementation through interlinking policies at different scales: NEPAD-EAP and the MDGs

Creating interlinkages between different policies and programmes is an effective way to develop synergies and enhance opportunities for using available resources more effectively. Interlinking policies at different scales can offer new opportunities for implementing institutions.

The environmental, social and economic challenges facing policymakers at the national level are as important as those at the sub-regional and regional levels, and often there are remarkable similarities. Through a process including national governments, the NEPAD-EAP prioritizes six environmental programme areas and three crosscutting issues. It also recognizes poverty as the main cause and consequence of environmental degradation and thus that there is an urgent need to halt the downward spiral of poverty and break the poverty-environment nexus. While it recognizes the value of major environmental agreements (MEAs) and global environmental policy processes, its focus is on responding to African national priorities. The MDGs, although globally defined targets, have to be realized in the national context, thus establishing linkages with regional, sub-regional and national programmes is critical to their realization. The MDGs can be effectively linked to NEPAD-EAP programme areas, which are:

- Combating land degradation, drought and desertification;

- Conserving Africa’s wetlands;

- Prevention, control and management of invasive alien species;

- Conservation and sustainable use of marine, coastal and freshwater resources;

- Combating climate change in Africa; and

- Transboundary conservation and management of natural resources.

All these areas are important for the realization of the MDGs, for example for the goals of alleviating extreme poverty and hunger, and achieving environmental sustainability. Table 3 shows how the MDGs are linked to the environment. The potential for creating effective interlinkages between these areas is dependent on governance systems, human resource availability and capacity, and funding. Table 4 highlights some of the interlinkages between NEPAD-EAP and MDGs.

In addition to the linkages between the NEPAD-EAP programme areas and MDG 7, there are also links to the other MDGs and to many MEAs. Several of these agreements are directly relevant to a specific area, while others have wider-reaching implications across all programme areas. The African Convention on the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (ACCNNR), for example, creates a broad framework for dealing with a range of environmental challenges and is applicable to all the programme areas of NEPAD-EAP. Both the CBD and the ACCNNR are dynamic, complex and non-linear interventions which encourage both thematic and institutional interlinkages. Partnership and institutional links can empower governmental institutions and agencies. For example, such an approach will enhance the capacity of African governments to integrate environment into social and economic processes, and into comprehensive development frameworks, such as the poverty reduction strategies. Interlinkages are necessary to meet the MDG targets, and Box 14 on MDG implementation in the West Indian Ocean islands subregion, illustrates this point. Success across the Africa region on achieving the MDG targets is shown in Appendix 1.

An interlinkages approach can lead to policy development which more effectively promotes trade, capacity-building and infrastructure development and addresses governance-related factors, such as high transaction costs, conflicts, debt and rent-seeking practices, and uncontrolled extractive industries and trade.

Combating land degradation, drought and desertification

The objectives of the NEPAD-EAP first programme area – combating land degradation, drought and desertification – cannot be achieved without strong links to the conservation of Africa’s wetlands, combating climate change and the transboundary conservation and management of natural resources. Land degradation is a major challenge for realizing sustainable development in Africa, affecting poverty reduction, peace and security, and economic and ecological health. About 110 million ha of Africa’s 494 million ha of vegetated land have been classified as degraded. Land degradation is a major impediment on Africa’s path towards meeting the MDGs; important impacts include escalating desertification, soil erosion, declining soil fertility, salinization and pollution by agrochemicals. Since 1950, an estimated 500 million hectares of Africa’s land have been affected by soil degradation, including at least 65 percent of agricultural land. Land (Land resources in Africa) gives an overview of this resource and the challenges and opportunities it offers.

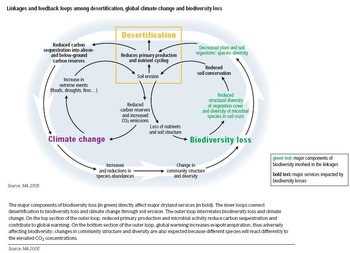

Desertification – a major environmental issue in Africa – is related to land degradation. According to the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MA), biological diversity is adversely affected by desertification, which also contributes to global climate change through soil and vegetation loss. Climate change may adversely affect biodiversity and exacerbate desertification due to increased evapotranspiration and a likely decrease in rainfall in drylands. Figure 2 highlights the interlinkages among desertification, global climate change and biodiversity loss.

The pressures leading to land degradation are socioeconomic and climatic. Poverty, conflict, intensive agriculture leading to soil loss and salinization, deforestation and land clearance for agriculture, and the cultivation of marginal lands are important contributors. Climate change pressures include reduced rainfall (or increased extreme rainfall events) and increased temperatures, which together lead to a reduction in vegetation cover and aggravated erosion by run-off and wind.

The responses to these pressures are at two levels. The first level concerns policies and management relating to land use and is potentially within the grasp of states to tackle through interdepartmental policy interventions and cooperative management at catchment and national levels, and in transboundary cases at international levels. Such interventions may relate to water use and agricultural policy, for example. The second level of responses, in respect of the climate change pressures, is at the international or intergovernmental level and is concerned with making representations for actions to tackle global warming, relevant at that level. In trying to address the challenges of land degradation, policymakers in Africa need to explore the synergies provided by the NEPAD-EAP, the MDGs (especially MDG 1 and 7), the CBD, the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD) and UNFCCC. The social, economic and environmental dimensions of land degradation are interlinked, and these cannot be considered in isolation if success is to be achieved. Interlinking these issues also provides for many different institutions and organizations which otherwise would not naturally collaborate to do so. Such interlinkages would contribute to enhancing human well-being and human sustainability.

As for land degradation, the responses are at two main levels. Interventions relate to land and water allocation and management and to policies dealing with pollution control, both from point sources and diffuse agricultural sources. Interdepartmental interests are likely to be relevant to the management of these pressures, with cooperative arrangements aiming for an equitable distribution of benefits from resource usage. The level of response in respect of the climate change pressures is at the international or intergovernmental level. At the global level the key multilateral environmental agreement (MEA) is Ramsar. Also significant, however, are the CBD and those conventions dealing with migratory species.

Conserving Africa's wetlands

Africa’s inland and coastal wetlands provide a rich and broad range of resources and services, for example fisheries, and ecosystem services that are under severe threat from a combination of human activities and climatic pressures. Fish accounts for 50 percent of animal protein sources in Africa; in some countries, including Liberia and Ghana, it constitutes as much as 65 to 70 percent of animal protein consumed, consequently protecting and enhancing this resource is important for meeting MDG target 2. Given this nutritional contribution, conserving wetlands is also important for realizing the MDG health-related targets. Goods-and-services derived from wetlands can contribute to improved local incomes and thus to the realization of MDG target 1, where better opportunities for local people to manage these as assets are created. The value of this resource, including the opportunities it offers for development and improving human wellbeing, and threats to it, are discussed more fully in Coastal and Marine Environments in Africa. Human-related pressures include:

- Landfills;

- Pollution from urban, industrial, mining and agricultural sources leading, for example, to eutrophication;

- Reduction of freshwater inflow as a result of water diversion, damming within the catchment, the lowering of groundwater tables, and deforestation. In the case of coastal wetlands, reduced freshwater inflow may increase salinity and threaten biodiversity; and

- Climate change, resulting in increased evaporation and reduced rainfall, and indirectly, over the longer term, sea-level rise.

This web of pressures indicates the need for policy responses based on interlinkages.

Conservation and sustainable use of marine, coastal and freshwater resources

The women of this gardening cooperative in Mutenda, Zimbabwe, rely on a nearby dam for irrigation for most of the year.

The women of this gardening cooperative in Mutenda, Zimbabwe, rely on a nearby dam for irrigation for most of the year.(Source: H. Wagner/IFAD)

The effective and equitable distribution and use of water may be the most important of all the NEPAD priority issues. The state of this resource, the challenges facing its management, and the opportunities it offers for development are discussed fully in Freshwater resources in Africa. Access to adequate, safe water significantly contributes to improved health and food production, an ability to earn income and self-reliance. Its management has impacts across spatial and temporal levels. Water allocation between countries may affect rights and opportunities at the local level, as well as the opportunities available to future generations. The importance of multi-stakeholder approaches, and in particular the inclusion of women at various planning levels, has been specifically acknowledged in the World Water Forums since the 1990s. Poor access to water and poor water quality may have a disproportional impact on women’s health and time: women are often the main collectors of water for household use and undertake most of the household tasks, such as cooking and washing, which use water. Inadequate investment in water supply systems and poor water governance regimes are the chief anthropogenic threats to water resources in Africa.

Coastal ecosystems, including wetlands, estuaries, mangroves and reef flats, are highly productive and rich in biodiversity, but they are at risk from physical disruption through, for example, urbanization and tourism infrastructure, eutrophication due to sewage and excessive agricultural nitrate run-off, oil pollution, solid waste and litter, and the discharge of effluents. As with other wetland systems, reduced freshwater availability due to damming in catchment and increased use of water for irrigation is also an issue. Climate change is an indirect pressure in that one effect is increasing sea surface temperatures leading to reef coral bleaching and mortality, while increased acidity of seawater may reduce the calcification of many marine organisms. The destruction of reef systems affects biodiversity and fish stocks, having major impacts on the well-being of coastal communities.

The responses to this range of pressures affecting water resources need consideration across sectors and at many levels, with national policies developed between government departments concerned with water resources, agriculture, industry, fisheries, environment etc, as well as at the intergovernmental level. There is also wide scope for community involvement in the conservation of these vital resources. There are many policy responses dealing with water management. The CBD applies to both freshwater and coastal and marine ecosystems and sets the general framework for biodiversity conservation. The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Fauna and Flora (CITES) regulates trade in endangered species. At the global level, the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) is the primary MEA setting out the rights and duties of nations in the use of the sea. The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Non-navigational Uses of International Watercourses provides an important framework for managing freshwater systems. There are many sub-regional and bilateral agreements which further refine this policy and managerial framework. Environment for Peace and Regional Cooperation in Africa discusses cooperative initiatives in river basin management.

Combating climate change

In order to effectively address the problems of climate change, policy responses are required at the international or intergovernmental level. African countries need to engage more effectively at this level and ensure that national and regional interests are better represented in the relevant global fora. This includes investing in cost-effective and environmentally sustainable energy, promoting climate-friendly carbon and technology markets, and mainstream responses to climate change and variability. Some responses at local to national levels may be appropriate, but these may be adaptive rather than combative, involving, for example, changes in land use. For example, reforestation may be appropriate over the long term, though the use of such approaches is controversial.

Addressing climate change is crucial to protecting food production systems. This may involve restoration and more effective management of desertified lands and is thus directly related to the achievement of targets 1 and 2 of MDG 1. Rising sea levels threaten coastal areas, and in particular small island developing states (SIDS), and thus have implications for the realization of many MDGs.

Climate change has, as discussed in The Human Dimension and earlier in this chapter, important implications for human health. A disproportional burden of this is felt in Africa, particularly by poor people, women, the elderly and children. Combating climate change is important then for attaining the MDGs’ health targets (Goals 4, 5 and 6).

Further reading

- Bojö, J. and Reddy, R.C., 2003b. Status and Evolution of Environmental Priorities in the Poverty Reduction Strategies:An Assessment of Fifty Poverty Reduction Strategy Papers. Environmental Economics Series, Paper No. 93.The World Bank,Washington, D.C.

- Bojö, J. et al., 2004. Environment. In A Sourcebook for Policy Reduction Strategies, Vol. 1: Core Techniques and Cross-Cutting Issues. (ed. Klugman, J.), pp. 375-401.The World Bank,Washington D.C.

- Energy Information Administration, 2003. Sub-Saharan Africa: Environmental Issues.

- Friends of the Earth, 1999. The IMF: Selling the Environment Short. Friends of the Earth,Washington, D.C.

- Heinzerling, L. and Ackerman, F., 2002. Pricing the Priceless: Cost-Benefit Analysis of Environmental Protection. Georgetown Environmental Law and Policy Institute, Georgetown University.

- MA, 2005. Ecosystems and Human Well-being: Desertification Synthesis. World Resources Institute, Washington, D.C.

- Peopleandplanet.net, 2003. Environmental connections.

- NEPAD, 2003. Action Plan for the Environment Initiative. New Partnership for Africa’s Development, Midrand.

- UN Millennium Project, 2005c. Investing in Development – A Practical Plan to Achieve the Millennium Development Goals. Earthscan, New York.

- UNEP, 2003. Global Environment Outlook 3.

- UNEP, 2004. GEO Yearbook 2003. United Nations Environment Programme, Nairobi.

- UNEP, 2005. Africa Environment Tracking – Issues and Developments. United Nations Environment Programme, Nairobi.

- UNEP, 2006. Africa Environment Outlook 2.

- UNEP, 2006. Africa Environment Outlook 2-ANNEXES.

|

|

| Disclaimer: This article is taken wholly from, or contains information that was originally published by, the United Nations Environment Programme. Topic editors and authors for the Encyclopedia of Earth may have edited its content or added new information. The use of information from the United Nations Environment Programme should not be construed as support for or endorsement by that organization for any new information added by EoE personnel, or for any editing of the original content. |