Gray wolves under the Endangered Species Act: Distinct population segments and experimental populations

The wolf was among the first animals protected under the Endangered Species Preservation Act, a predecessor to the current Endangered Species Act (ESA). In 1978 the gray wolf was listed as endangered in all of the conterminous 48 states except Minnesota, where it was listed as threatened. With the exception of experimental populations established in the 1990s, the protections for the gray wolf have been diminishing since that date, as wolf populations have increased in some areas. The use of distinct population segments (DPSs), a term created in the 1978 ESA amendments, has played a role in that reduced protection. DPSs allow vertebrate species to be divided into distinct groups, based on geography and genetic distinctions.

ESA protection for DPSs has changed back-and-forth since the first DPSs—Western and Eastern—were proposed in 2003. In 2004, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) determined that those DPSs no longer needed the protection of the ESA and so were delisted. The Western and Eastern DPS designations and delistings were nullified by courts. In 2007, FWS designated and delisted the Western Great Lakes DPS, and in early 2008, FWS designated and delisted the Northern Rocky Mountains DPS. However, courts found both delistings flawed and vacated the rulemaking. In December 2008 FWS returned the wolves in the Western Great Lakes and parts of the Northern Rocky Mountains areas to their former protected status, eliminating the DPSs. That same rulemaking redesignated wolves in south Montana, southern Idaho and all of Wyoming as “nonessential experimental populations,” which they were prior to the DPS efforts. The rulemaking took effect on December 11, 2008, meaning it appears to be outside the scope of White House Chief of Staff Rahm Emanuel’s memorandum of January 20, 2009, halting the effect of all non-final regulations pending further review. An additional rulemaking to delist Western Great Lakes and Northern Rocky Mountain wolves (except within Wyoming) was announced on January 14, 2009, but was not published.

This report analyzes the DPS designation process as it is applied to the gray wolf. It also examines experimental populations of wolves under the ESA and their protections. As part of its oversight responsibilities, Congress has conducted hearings on the Fish and Wildlife Service’s application of science to endangered species.

Contents

- 1 Background and regulatory history

- 2 Wolf populations: A taxonomic view

- 2.1 Experimental populations

- 2.2 Experimental populations of gray wolves

- 2.3 Species and distinct population segments

- 2.4 Gray wolf distinct population segments

- 2.5 Section 4(d) Rules Special rules may be issued for both distinct population segments and experimental populations. When a species is designated as threatened, rather than endangered, FWS has discretion to issue special rules for that species. (Endangered species have protections that are expressly stated in the act.) Under Section 4(d) of the ESA, FWS may decide how the protections of the act related to taking, or harming of the threatened species, are applied. These regulations are called Section 4(d) rules or special rules. A DPS is treated like a species under the act; therefore, the special regulation provision also applies to threatened DPSs. Under Section 10(j)(3)(C), experimental populations are treated as threatened species, and so are also covered under this provision. Special rules provide customized protection that FWS deems necessary and advisable for the species’ conservation. FWS is not limited in determining the protections and can allow the full range of protections in the act to threatened species. The special rules are promulgated in Title 50 (Part 17) of the Code of Federal Regulations. (Gray wolves under the Endangered Species Act: Distinct population segments and experimental populations)

- 2.5.1 Section 4(d) Rules for Gray Wolves. According to FWS, Section 4(d) rules are intended to reduce conflicts between the provisions of the act and needs of people near the areas occupied by the species. This type of special rule has been in effect for the threatened gray wolves in Minnesota for many years, and was extended to gray wolves in other states, when and where the wolf was downlisted. Under the rule for Minnesota, individual wolves that have preyed on domestic animals can be killed by designated government agents. FWS asserts that this rule avoids even larger numbers of wolves being killed by private citizens who otherwise might take wolf control into their own hands.[69]In 2003 as part of the rulemaking that was vacated, FWS issued Section 4(d) rules for two DPSs: Eastern and Western. The special rules would have allowed individuals to kill Western DPS wolves in the act of attacking livestock on private land, and to harass wolves near livestock. Permits to kill wolves could also be issued to landowners who showed wolves routinely were present and formed a significant risk to livestock. FWS said that, as in Minnesota, the rule would “increase human tolerance of wolves in order to enhance the survival and recovery of the wolf population.”[70] Michigan and Wisconsin citizens would be able to kill any wolf within one mile of killed livestock, and in other Eastern states beside Minnesota, any lethal measures could be used within four miles of such a site. [71] This rule was vacated, as discussed earlier in Litigation Regarding Western and Eastern DPSs. (Gray wolves under the Endangered Species Act: Distinct population segments and experimental populations)

- 2.5.2 Section 4(d) rules for Yellowstone and Idaho experimental populationsIn 2005, after the FWS found that the wolf population had exceeded its minimum goals of 30 breeding pairs for Yellowstone and Central Idaho, it issued a rule to manage wolves where they had an unacceptable impact on ungulate populations.[72] This 2005 Rule modified the provisions put in effect when the wolves were first introduced, which stated that “wolves could not be deliberately killed solely to resolve predation conflicts with big game.”[73] The 2005 Rule allowed States and Tribes in the area to kill wolves where it was shown they were adversely affecting the populations of deer, antelope, elk, big horn sheep, mountain goats, bison, or moose in the area. Before the states and tribes could act, they were required to submit the plan for peer review, public comment, and FWS approval. Data at the time, from many sources cited by FWS, showed that wolf predation was “unlikely to be the primary cause of a reduction of any ungulate herd or population in Idaho, Wyoming, or Montana.”[74] FWS reported that more wolves were killed in 2007 and 2008 than were cattle.[75] In 2008, the wolf population in the area was estimated at 1,463.[76] In 2008 FWS changed the special rule.[77] FWS determined that the definition of unacceptable impact had to be altered, as wolves were not the primary cause in ungulate population decreases. Accordingly, the definition was modified to mean: “Impact to a wild ungulate population or herd where a State or Tribe has determined that wolves are one of the major causes of the population or herd not meeting established State or Tribal population or herd management goals.”[78] Public and peer reviews are still required. The plan allows a state to kill wolves, provided the experimental population does not go below 20 breeding pairs in the state.[79] The 2008 Rule also expands the provision for killing wolves when they are in the act of attacking livestock or dogs. The 2005 Rule allowed an individual to “take” a wolf that was in the act of attacking stock animals or dogs on private property. The 2008 Rule allows individuals to take wolves that are in the act of attacking livestock or dogs on public lands as well, except for National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) property.[80] (Gray wolves under the Endangered Species Act: Distinct population segments and experimental populations)

- 2.6 References

- 2.7 Attached Files

Background and regulatory history

The history of gray wolf protection is interconnected with the history of the Endangered Species Act (ESA) (16 U.S.C. §§ 1531- 1543). Gray wolf protection began at the nascency of the ESA, when it was one of the first species covered under the Endangered Species Protection Act of 1966.[1] As the ESA has been amended, so has gray wolf protection. The act provides the basis for determining which species are threatened and endangered, and how those listed species will be protected. Amendments allow consideration of distinct groups within species for protection. The act allows introduction of experimental populations to areas where the species no longer exists, and provides regulatory protections for that introduction. Each of these elements will be discussed in this report generally, and more specifically in the context of gray wolf protection.

For centuries, wolf populations have been under attack by humans. The effort to reduce or eliminate the species was designed to protect humans from a perceived direct threat to humans or to protect livestock or favored game species. Wolves were eventually eliminated in most states in an effort supported by the science community at the time. But coinciding roughly with the forester Aldo Leopold’s essay, “Killing the Wolf,” in A Sand County Almanac in 1948, this view began to change. Leopold wrote:

I was young then, and full of trigger-itch; I thought that because fewer wolves meant more deer, that no wolves would mean hunters’ paradise. But after seeing the green fire die, I sensed that neither the wolf nor the mountain agreed with such a view.... Since then I have lived to see state after state extirpate its wolves. I have watched the face of many a newly wolfless mountain, and seen the south-facing slopes wrinkle with a maze of new deer trails. I have seen every edible bush and seedling browsed, first to anaemic desuetude, and then to death.

In 1967 when the gray wolf was listed under the first version of the Endangered Species Act, it was listed in two subspecies, the eastern timber wolf, and the northern Rocky Mountain wolf.[2] In 1978 the gray wolf was relisted as endangered at the species level throughout the lower 48 states, with the exception of Minnesota, where it was listed as threatened.[3] In the 1990s actions were taken to reintroduce the wolf into areas where it had been eradicated. Experimental populations were introduced into the Yellowstone area and central Idaho,[4] and in Arizona, New Mexico and Texas.[5] Efforts to protect the wolf have always been controversial, however. The Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) reports receiving, and denying, “several petitions” to delist the wolf in all or part of the 48 states.[6] Additionally, in 1987 legislation was introduced to remove the gray wolf from the ESA protected list.[7] The amendment failed.

Wolf populations: A taxonomic view

Like many large mammals, such as bears (Ursus arctos), mountain lions (Felis concolor), and white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus), gray wolves (Canis lupus) have a complicated, even convoluted, taxonomic history. Variations in color, size, and bone structure have led some mammalogists to name wolves in various areas as different subspecies or populations, where other credible experts would see only a single species with variability. Here are scientific definitions of a few key terms:

- A population is a group of “organisms of the same species that inhabit a specific area.”

- A species is a “naturally [occurring] population or a group of potentially interbreeding populations that is reproductively isolated(i.e.,cannot exchange genetic material) from other such populations or groups.”

- A subspecies is a “taxonomic category that subdivides species into morphologically distinct groups of individuals representing a step toward the production of a new species, although they are still fully capable of interbreeding. Subspecies are usually geographically isolated.”

- Taxon, or the plural taxa, is defined as: “a grouping of organisms given a formal taxonomic name at any rank: species, genus, family, order, class, division, phylum, or kingdom.”[8]

These terms may appear clear; however, there are no simple measures to draw unequivocal distinctions. Biologists commonly divide their colleagues into “lumpers” and “splitters,” based on their inclinations in classifying organisms. As the names suggest, lumpers are those who tend to minimize differences, and see one or a few species, perhaps with some variations, while splitters would tend to emphasize those differences, dividing a species into many subspecies, or populations. For wolves, which are (or were) found in temperate and polar areas throughout the Northern Hemisphere, some observers (splitters) would argue that there are as many as 24 subspecies in North America and eight in Europe and Asia.[9] More recently, lumpers have had the upper hand, and FWS recognizes two species (gray and red wolves), and divides the gray wolf into six “distinct population segments,” based in part on administrative and procedural criteria.[10]

While confusing to the non-scientist, this muddled state of taxonomic affairs is entirely predictable for several reasons. First, wolves are extremely wide-ranging, both as a species and as individuals, so interbreeding among them could certainly muddy the picture. Second, the consistency of variations over time is hard to determine, since long-range studies of long-lived species are rare. Third, evolutionary change does not stop, and wolves are an adaptable species, as shown by their behavior and by their presence in a tremendous variety of ecosystems.[11] If FWS scientists’ choice of state boundaries to delineate wolf populations is criticized as arbitrary, the debate among academic scientists also has an air of informed judgment— and there is no reason to predict that either debate will end any time soon.

Experimental populations

In 1982 Congress added the concept of experimental populations to the ESA as a way of reintroducing species without severe restrictions on the use of private and public land in the area.[12] Experimental population designations are sometimes referred to as Section 10(j) rules. The practice allows introduction of a species outside its current range to restore it to its historic range.

Two criteria must be met for an experimental population to comply with the law. First, the Department of Interior (DOI) must have authorized the release of the population. Second, the population must be wholly separate geographically from other animals of that species.[13] Congress required the separation so that the introduced population could be clearly distinguished.

Members of an experimental population are considered to be threatened under the act, and thus, can have special rules written for them.[14] In fact, Congress referred to special rules for experimental populations as a way to reduce public opposition to the release of certain species, using the red wolf as an example.[15] Congress suggested in a report that the special regulations could allow killing members of the species:

The committee fully expects that there will be instances where the regulations allow for the incidental take of experimental populations .... The committee also expects that, where appropriate, the regulations could allow for the directed taking of experimental populations. For example, the release of experimental populations of predators, such as red wolves, could allow for the taking of these animals if depredations occur or if the release of these populations will continue to be frustrated by public opposition.[16]

Unlike distinct population segments (DPSs), experimental populations may not necessarily have the same protections under the ESA. Section 10 requires FWS to determine whether the experimental population is of a species that is in imminent danger of extinction. That decision is based on whether the loss of the population would appreciably diminish the species’ prospect for survival. If so, the experimental population is deemed essential and is treated as an endangered species. Currently, there are no essential experimental populations. If it is deemed nonessential, the experimental population is treated as a species that is proposed for listing as threatened or endangered. There is no critical habitat designation for an experimental population if it is nonessential. Also, federal actions that may take a member of the population do not require a Section 7(a)(2) consultation under the ESA, unless the species is in a national wildlife refuge or a national park, although agencies are required to confer under Section 7(a)(4).

Examples of species with nonessential experimental populations are the Colorado pikeminnow(or squawfish), the southern sea otter, the gray wolf in the Southwest and in the Yellowstone area, theblack-footed ferret, and the whooping crane.

Experimental populations of gray wolves

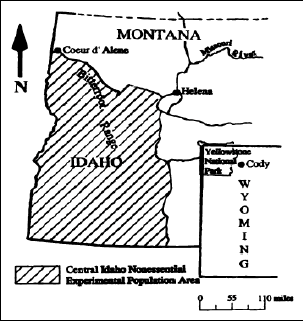

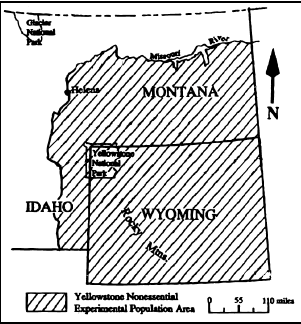

Despite near-eradication of the wolf in the lower 48 states, some of the wolf’s old territories survived, though in a highly modified form. At the end of the 20th century, FWS planned to reintroduce the wolf to parts of its historic range, using the experimental population provisions of the ESA. No reintroduction was more controversial than that in the greater Yellowstone ecosystem, where all other large vertebrates were still present, and where many scientists agreed that elk populations—a favorite wolf prey—had reached harmful levels. In 1995 and 1996 FWS released 66 gray wolves from Canada in Yellowstone and central Idaho. (See Figure 1 and Figure 2).

When wolves were returned, the science community was nearly giddy anticipating the potential effects from a first-ever return of a major predator to a nearly intact ecosystem. The excitement was intense partly because the Yellowstone area was already well studied, with long-term data on many species, including both competitors (e.g., coyotes and, to some extent, grizzlies) and potential prey (e.g., elk, moose, and bison). As scientists had expected, wolves had a profound effect on elk, but there is also evidence of effects that were less predictable — on aspens, cottonwoods, beavers, beetles, mice, red foxes, ravens, and voles, among others.[17] However, the road to the reintroduction was, and still is, fraught with litigation and controversy.

Wolves also had been exterminated in the southwest. FWS recognized a separate subspecies, the Mexican wolf (Canis lupus baileyi), which was probably gone from the United States but found in very low numbers in Mexico. After a cooperative and successful captive breeding program of wolves obtained from Mexico, reintroduction was begun in 1998, in an area centered in the Apache National Forest in Arizona and the Gila National Forest in New Mexico. In both the Yellowstone and the Southwest cases, litigation was a major factor in the reintroduction effort.

Yellowstone litigation

While the recovery plan for the Northern Rockies gray wolf acknowledged that the species may have to be reintroduced into the area around Yellowstone National Park, that decision was controversial. Suit was filed to compel FWS to bring some wolves to Yellowstone. However, the court ruled the action was moot as it could not compel FWS to act,[18] and an appropriations rider in 1992 blocked any funding for bringing the wolf to the area.

In 1995 and 1996 FWS released 66 gray wolves from Canada in Yellowstone and central Idaho. A man accused of violating the ESA for killing one member of the Yellowstone experimental population argued that he had killed a Canada wolf, which was not an endangered species. This argument failed. The Ninth Circuit upheld the regulations for the experimental population, holding that once the wolves from Canada were introduced into the park, they became protected under the ESA.[19]

Another lawsuit argued that because the Yellowstone experimental population may interact and breed with the few lone wolves in the area the experimental population designation violated Section 10(j) of the ESA. (The lone wolves may have been remaining wolves that somehow survived extermination, feral wolves, or wolves naturally dispersing from farther north.) Section 10(j) requires that experimental populations must be “wholly separate geographically from nonexperimental populations of the same species.”[20] The district court ruled that the Yellowstone population would have to be removed. However, the Tenth Circuit overruled the decision.[21] The court rejected the argument that the legislative history of experimental populations (as discussed earlier in this report) meant that the experimental population must be separate from every naturally occurring individual animal. The court deferred to the DOI management plan for the reintroduction, finding it did not conflict with the statute.

A more recent claim disputed FWS management of the wolves. A rancher argued the agency failed to control wolves that were preying on livestock. After FWS killed three wolves, including the lead male wolf of the offending pack, no more depredations were found. The court dismissed the claims on procedural grounds.[22]

After courts ruled that FWS had not satisfied the requirements of the ESA in making distinct population segments in the Northern Rockies area, FWS re-established the non-essential experimental populations of the Yellowstone and Central Idaho areas, now spread to all of

Wyoming, the southern half of Montana, and all but the northern panhandle of Idaho.

Southwest litigation

The reintroduction of the wolf to the Southwest was no less controversial. Ranchers sued, claiming the action violated the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), as well as the ESA. The court found for FWS, even though livestock owners and FWS had different estimates as to the impact of the wolves on domesticated stock.[23]

Once the wolf was reintroduced to the Southwest, environmentalists sued FWS for not acting to modify the reintroduction regulations.[24] The action was dismissed as moot. The area remains a center of intense public controversy about wolves.

Species and distinct population segments

If the scientific community is somewhat inconsistent in identifying species, the law has fared no better. The ESA definition of species has changed since the early days of the act. In 1973 the definition included “any subspecies of fish or wildlife or plants and any other group of fish or wildlife of the same species or smaller taxa in common spatial arrangement that interbreed when mature.”[25] In 1978, Congress amended that definition to include the term distinct population segment (DPS) and was limited to vertebrate DPS's only.[26] The change was controversial.

The General Accounting Office (GAO) (now the Government Accountability Office) recommended limiting the definition of species to higher taxonomic categories than populations, and exclude all distinct populations, including geographically separated populations.[27] GAO proposed the following definition: “The term ‘species’ includes any subspecies of fish, wildlife, or plants.”[28] GAO found the 1973 definition to be overly broad:

We found that Interior’s Fish and Wildlife Service is listing populations of species in limited geographical areas as endangered or threatened instead of listing the entire species. This has occurred because the Service has interpreted the definition of “species” to include populations, regardless of their size, location, or total numbers. Using the Service’s interpretation of the term, squirrels in a specific city park could be listed as endangered even though there is an abundance of squirrels in other parks in the same city and elsewhere. Such listings had increased the number of potential conflicts between endangered and threatened species and federal, state, and private projects and programs.[29]

Congress did not follow the GAO recommendation. It agreed with FWS that the service needed to be able to adopt different management practices for different populations, based on their need. A Senate committee report discussing populations said “the committee agrees that there may be instances in which FWS should provide for different levels of protection for populations of the same species,” although it advised the practice be used “sparingly and only when the biological evidence indicates that such action is warranted.”[30]

Thus, Congress revised and limited the definition of species in 1978 by eliminating taxonomic categories below subspecies from the definition, except for vertebrates.[31] The revised, and still current, definition is: “any subspecies of fish or wildlife or plants, and any distinct population segment of any species of vertebrate fish or wildlife which interbreeds when mature.”[32] However, the phrase distinct population segment had no meaning in the scientific community outside of the ESA, and was not used in endangered species listings for nearly two decades.

Regulatory history of distinct population segments

A DPS generally refers to a portion of a listed species, separated from the rest of the species by genetic distinction and range. The legislative history offers two examples of when different protection is appropriate within a species: 1) when a U.S. population of an animal is near extinction even though another population outside the United States is more abundant; and 2) where conclusive data have been available only for certain populations of a species and not for the species as a whole.[33]

In 1996 a policy regarding DPS was introduced by FWS (hereinafter referred to as “the Policy”).[34] The Policy contains the criteria that must be met for protection of a species at the population level. First, the population segment must be discrete. Factors considered to determine discreteness are whether the segment is “markedly separated from other populations of the same taxon as a consequence of physical, physiological, ecological, or behavioral factors.”[35] Discreteness can also be found if the population is delimited by international governmental boundaries. Although state boundaries are frequently used to describe a DPS, they cannot be used under the Policy to determine discreteness.

Next, the population segment must be found to be significant, meaning its demise would be an important loss of genetic diversity.[36] Four factors are listed in the policy for determining a species’ significance: 1) persistence of the segment in an ecological setting unusual or unique for the taxon; 2) evidence that loss of the DPS would result in a significant gap in the range of the taxon; 3) evidence that the DPS represents the only surviving natural occurrence of a taxon within its historic range; or 4) evidence that the DPS differs markedly from other populations of the species in its genetic characteristics. Genetic evidence is allowed to be considered but is not required. The policy indicates that “available scientific evidence of the discrete population segment’s importance” will be considered in finding significance, but does not specify the best available scientific evidence.

If a species is found to be both discrete and significant, then its status is reviewed to see whether it is endangered or threatened. A DPS species is reviewed to determine whether it should be listed under exactly the same procedures as any other listing. The listing determination is to be based solely on the “best scientific and commercial data available.”[37]

Pros and cons of distinct population segments

Agency efficiency and focus were two intended benefits of DPSs, according to the Policy. The Policy said determining DPSs will “concentrate ... efforts toward the conservation of biological resources at risk of extinction.”[38] The Policy suggested the practice of using DPSs could help endangered species by focusing on smaller groups:

This may allow protection and recovery of declining organisms in a more timely and less costly manner, and on a smaller scale than the more costly and extensive efforts that might be needed to recover an entire species or subspecies. The Services’ & the National Marine Fisheries Service’s ability to address local issues (without the need to list, recover, and consult rangewide) will result in a more effective program.[39]

The FWS has followed Congress’s admonition to apply the practice “sparingly.” According to FWS, only 39 of the 374 vertebrates listed under the ESA are DPSs.

Some have criticized DPSs as being used to remove ESA protections from certain segments of a listed species. In three cases the listing classification of DPSs appears to be used solely to remove animals from protected status. The DPS designation and the delisting occurred on the same day in the same Federal Register notice. Those three cases are:

- Columbian white-tailed deer, Douglas Co. DPS — July 24, 2003;

- Gray wolf, Western Great Lakes DPS — February 8, 2007; [40]

- Grizzly bear, Yellowstone DPS — March 29, 2007. [41]

- Gray wolf, Northern Rocky Mountains DPS—February 28, 2008.[42]

One district court suggested that this practice was contrary to the ESA, which was brought before it on a challenge to the Western Great Lakes DPS designation and delisting.[43] The court said the ESA did not unambiguously allow a species to be designated as a DPS at the same time it was delisted, noting that a goal of the act was to protect species. The court vacated the designation and the delisting, and remanded the matter to the FWS.

In other examples, the species has become downlisted (having its status dropped from endangered to threatened) the same day as being designated a DPS:

- Gray wolf, Western DPS — downlisted April 1, 2003;

- Gray wolf, Eastern DPS — downlisted April 1, 2003.

However, for many more species, the designation of a DPS improved its protection status. Here are some examples:

However, for many more species, the designation of a DPS increased its protection status, by protecting a group, even though the species as a whole was not covered by the act.[44] Here are some examples:

- California Bighorn Sheep, Sierra Nevada DPS — listed as endangered January 3, 2000;

- Canada Lynx, contiguous U.S. DPS — listed as threatened March 24, 2000;

- Atlantic Salmon, Gulf of Maine DPS — listed as endangered November 17, 2000;

- Dusky Gopher Frog, Mississippi DPS — listed as endangered December 4, 2001;

- Pygmy Rabbit, Columbia Basin DPS — listed as endangered March 5, 2003;

- California Tiger Salamander, Sonoma County DPS — listed as endangered March 19, 2003;

- Northern Sea Otter, Southwest Alaska DPS — listed as threatened August 9, 2005.

Gray wolf distinct population segments

Since the issuance of the Policy, FWS has pursued dividing the gray wolf into more DPSs.[45] These DPSs are considered separately from the experimental populations. All designations were challenged in federal court (the lawsuits will be discussed later in this report), and each court rejected the FWS’s action. In 2003 FWS divided wolves into three DPSs: Western, Eastern and Southwestern.[46] This rulemaking then downlisted the Eastern and Western DPSs from endangered to threatened under the ESA. At the same time, gray wolves were removed from protection in 14 southern and eastern states where they have not occurred in recent times. This rulemaking was vacated by two federal courts.

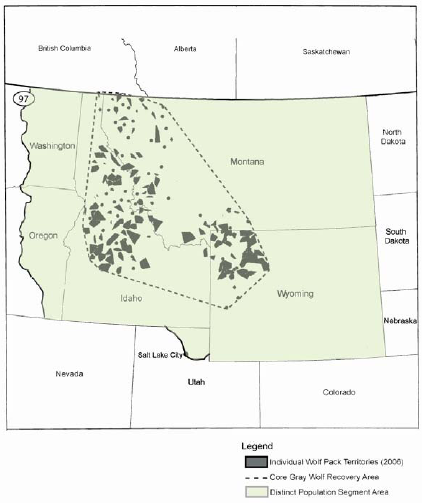

After the 2003 DPS rulemaking was nullified, two other DPSs of the gray wolf were proposed: Northern Rocky Mountain, and Western Great Lakes.[47] The Western Great Lakes population was declared a distinct population segment in 2007, and delisted at the same time.[48] That final rule was vacated by the District Court for the District of Columbia.[49] On the same date as the Western Great Lakes rule, FWS proposed designating the Northern Rockies DPS and delisting the population (See Figure 3), except for the population in Wyoming because Wyoming’s state laws were found not to provide enough protection for the wolf.[50] Wyoming’s population was subsequently delisted.[51] Following litigation, in September 2008, FWS voluntarily vacated the determination that both designated the Northern Rockies DPS and delisted it, returning wolves in that area to the list of endangered and threatened species.[52]

As a result, from 1978 to 2008 wolves in the United States were listed in all of the available categories for a vertebrate species: (a) never listed (Alaska); (b) delisted (the DPSs described above); (c) experimental (Southwest; Yellowstone and Central Idaho); (d) threatened (Minnesota); and (e) endangered (every wolf that was not a DPS, experimental population, or in Minnesota).

As noted above, wolf taxonomy is complex, but the choices made in distinguishing DPSs have significant effects. In particular, if FWS agrees with taxonomic lumpers, and recognizes only a few DPSs, then the recovery task becomes simpler than it would be if many DPSs are recognized. Some observers would argue that because wolf sightings in Northern New York and New England are very rare, those animals should represent a portion of a DPS which extends into Canada, and therefore entitle them to recovery in their own plan.[53] In addition, whether a few lone wolves inhabit the area or simply visit it occasionally, reintroduction proponents would further argue that an abundance of apparently suitable habitat and high prey populations make the region suitable for recovery efforts.

Regardless of the merits or demerits of this argument and the surrounding facts, Northeast wolf designation hinges on a taxonomic assessment that the language of the ESA elevates far beyond an academic debate between lumpers and splitters. FWS considers the wolves (if any) in that area to be part of the same DPS of much larger area.[54] And if a portion of the DPS reaches its recovery goals, FWS — arguing that it does not have legal responsibility to recover a species throughout its historic range — would be relieved of the burden of recovering the species in the remainder of the DPS’s range. Thus, the decision of whether to mount an effort to recover relatively rare wolves in the remote Northeast (and certain other areas) depends on two questions, one legal and one scientific:

- Does ESA require that a species be recovered in all or most of the remaining areas of suitable habitat?

- Do (or did) the wolves of the Northeast constitute a DPS, and if none remain, should presumably genetically similar wolves in nearby parts of Canada be used to repopulate the area?

Litigation regarding western and eastern DPSs.

The rule designating three DPSs of the gray wolf (Western, Eastern, and Southwestern) and downlisting the Western and Eastern DPSs in 2003 was challenged in two federal district courts. The plaintiff environmental groups before the District Court for the District of Oregon disputed how the DPS ranges were designated. They argued that FWS considered only where the wolves were currently located when determining their viability. This allowed FWS to count wolves only in the areas they occupied. However, areas outside of the wolves’ current range were suitable habitat, according to FWS, although no wolves were present, but FWS did not include those areas in defining the DPS ranges. The plaintiffs argued that this method was contrary to the ESA and prior caselaw, because the act requires that a species is endangered if it is at risk of extinction in “all or a significant portion of its range.” The court agreed that FWS had violated the ESA by equating the wolves’ current range with a “significant portion of its range.”[55] The court vacated the rule, effectively eliminating the three DPSs.

The other suit was before the District Court for the District of Vermont, which issued a decision eight months after the Oregon court. The plaintiffs in Vermont challenged the final rule’s designation of an Eastern DPS, which changed the proposed rule’s two DPSs for that area: a Northeast DPS and a Western Great Lakes DPS. The court found procedural flaws and also that the FWS failed to consider the “significant portion of its range” in a way consistent with the ESA.[56] The court criticized FWS’s method before vacating the rule: “The FWS simply cannot downlist or delist an area that it previously determined warrants an endangered listing because it ‘lumps together’ a core population with a low to non¬existent population outside of the core area.”[57]

Litigation Regarding the Northern Rocky Mountains DPS

In July 2008 the District Court for the District of Montana issued a preliminary injunction halting the effectiveness of the FWS delisting of the Northern Rockies DPS.[58] The delisting had added Wyoming to Idaho and Montana as states that had adequate wildlife management programs to support populations above recovery levels.[59] The July order rejected FWS’s contention that there was genetic exchange between the Yellowstone experimental population and the Northern Rockies animals. (Figure 3 shows the distribution of wolf packs in the two areas.) Without sufficient genetic exchange, the isolated wolf populations would not be genetically diverse enough to avoid inbreeding, and therefore could not be termed “recovered.” The court also found that the states’ management plans did not seem adequate to support wolf recovery levels. The order reinstated the wolf as endangered until final disposition. In September 2008, FWS voluntarily moved to withdraw the final rule that both designated the Northern Rockies DPS and declared it recovered.[60] Wolves in that area returned to being nonessential experimental populations with special regulations allowing takes.[61] In January 2009, FWS announced that it planned to delist the Northern Rockies population, with the exception of the Wyoming population.[62] (See below at “Section 4(d) Rules for Yellowstone and Idaho Experimental Populations.”) It appears that FWS will not issue the rule, however, in light of the January 20, 2009 memorandum by White House Chief of Staff Rahm Emanuel halting publication of rules that were not reviewed by an official appointed by President Obama.[63]

Litigation Regarding the Western Great Lakes DPS

In September 2008 the District Court for the District of Columbia vacated the final rule that designated the Western Great Lakes gray wolf as a DPS and delisted that DPS.[64] Unlike the holding in the Northern Rockies DPS case, this decision focused on the procedure, not the science, behind the designation and delisting rule. The plaintiffs claimed that FWS had violated the act by issuing the designation and delisting simultaneously. FWS argued that the ESA “unambiguously” supported its rulemaking. The court found the ESA was not unambiguous, in light of the act’s purpose in conserving species. The action was remanded to the agency to find a “reasonable explanation” for its interpretation that the ESA supports its designation/delisting rule.[65]

FWS reinstated the Western Great Lakes DPS as an endangered species in December 2008.[66] In January 2009, FWS announced it was delisting the DPS,[67] but the rulemaking was halted.[68] Those wolves are considered endangered except for in Minnesota where they are listed as threatened.

Section 4(d) Rules for Gray Wolves. According to FWS, Section 4(d) rules are intended to reduce conflicts between the provisions of the act and needs of people near the areas occupied by the species. This type of special rule has been in effect for the threatened gray wolves in Minnesota for many years, and was extended to gray wolves in other states, when and where the wolf was downlisted. Under the rule for Minnesota, individual wolves that have preyed on domestic animals can be killed by designated government agents. FWS asserts that this rule avoids even larger numbers of wolves being killed by private citizens who otherwise might take wolf control into their own hands.[69]In 2003 as part of the rulemaking that was vacated, FWS issued Section 4(d) rules for two DPSs: Eastern and Western. The special rules would have allowed individuals to kill Western DPS wolves in the act of attacking livestock on private land, and to harass wolves near livestock. Permits to kill wolves could also be issued to landowners who showed wolves routinely were present and formed a significant risk to livestock. FWS said that, as in Minnesota, the rule would “increase human tolerance of wolves in order to enhance the survival and recovery of the wolf population.”[70] Michigan and Wisconsin citizens would be able to kill any wolf within one mile of killed livestock, and in other Eastern states beside Minnesota, any lethal measures could be used within four miles of such a site. [71] This rule was vacated, as discussed earlier in Litigation Regarding Western and Eastern DPSs. (Gray wolves under the Endangered Species Act: Distinct population segments and experimental populations)

Section 4(d) rules for Yellowstone and Idaho experimental populationsIn 2005, after the FWS found that the wolf population had exceeded its minimum goals of 30 breeding pairs for Yellowstone and Central Idaho, it issued a rule to manage wolves where they had an unacceptable impact on ungulate populations.[72] This 2005 Rule modified the provisions put in effect when the wolves were first introduced, which stated that “wolves could not be deliberately killed solely to resolve predation conflicts with big game.”[73] The 2005 Rule allowed States and Tribes in the area to kill wolves where it was shown they were adversely affecting the populations of deer, antelope, elk, big horn sheep, mountain goats, bison, or moose in the area. Before the states and tribes could act, they were required to submit the plan for peer review, public comment, and FWS approval. Data at the time, from many sources cited by FWS, showed that wolf predation was “unlikely to be the primary cause of a reduction of any ungulate herd or population in Idaho, Wyoming, or Montana.”[74] FWS reported that more wolves were killed in 2007 and 2008 than were cattle.[75] In 2008, the wolf population in the area was estimated at 1,463.[76] In 2008 FWS changed the special rule.[77] FWS determined that the definition of unacceptable impact had to be altered, as wolves were not the primary cause in ungulate population decreases. Accordingly, the definition was modified to mean: “Impact to a wild ungulate population or herd where a State or Tribe has determined that wolves are one of the major causes of the population or herd not meeting established State or Tribal population or herd management goals.”[78] Public and peer reviews are still required. The plan allows a state to kill wolves, provided the experimental population does not go below 20 breeding pairs in the state.[79] The 2008 Rule also expands the provision for killing wolves when they are in the act of attacking livestock or dogs. The 2005 Rule allowed an individual to “take” a wolf that was in the act of attacking stock animals or dogs on private property. The 2008 Rule allows individuals to take wolves that are in the act of attacking livestock or dogs on public lands as well, except for National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) property.[80] (Gray wolves under the Endangered Species Act: Distinct population segments and experimental populations)

References

- Where listed as an experimental population;

- Minnesota, Wisconsin, Michigan, eastern North Dakota (that portion north and east of the Missouri River upstream to Lake Sakakawea and east of the centerline of Highway 83 from Lake Sakakawea to the Canadian border), eastern South Dakota (that portion north and east of the Missouri River), northern Iowa, northern Illinois, and northern Indiana (those portions of IA, IL, and IN north of the centerline of Interstate Highway 80), and northwestern Ohio (that portion north of the centerline of Interstate Highway 80 and west of the Maumee River at Toledo); and

- Mexico. See FWS website

| Disclaimer: This article is taken wholly from, or contains information that was originally published by, the Congressional Research Service. Topic editors and authors for the Encyclopedia of Earth may have edited its content or added new information. The use of information from the Congressional Research Service should not be construed as support for or endorsement by that organization for any new information added by EoE personnel, or for any editing of the original content. |

Note: The first version of this article was drawn from RL34238 Gray Wolves Under the Endangered Species Act: Distinct Population Segments and Experimental Populations by Kristina Alexander and M. Lynne Corn, Congressional Research Service on February 13, 2009.