Fin whale

The Fin Whale (scientific name: Balaenoptera physalus) is a very large marine mammal, in the family of Rorquals (Balaenoptera), part of the order of cetaceans.

This endangered species, named after its distinctive dorsal fin, is the second largest animal on Earth after the Blue Whale.

The Fin Whale is a baleen whale, meaning that instead of teeth, it has long plates which hang in a row (like the teeth of a comb) from its upper jaws. Baleen plates are strong and flexible; they are made of a protein similar to human fingernails. Baleen plates are broad at the base (gumline) and taper into a fringe which forms a curtain or mat inside the whale's mouth. Baleen whales strain huge volumes of ocean water through their baleen plates to capture food: tons of krill, other zooplankton, crustaceans, and small fish.

Fin whales tend to occur in pairs or in groups known as pods that usually contain around six or seven individuals; although larger groups have been observed. This species spends spring and early summer in cold feeding grounds at high latitudes, migrating to more tropical areas for winter and the breeding season.

Northern hemisphere and southern hemisphere populations never meet because the seasonal patterns are reversed in the two hemispheres, and so they migrate to the equator at different times of year.

This marine mammal mates in winter, and as gestation takes about 11 months, births occur in the winter breeding grounds where conception took place. A single calf is produced, which is suckled for six to seven months; after weaning, a calf travels with its mother to the feeding grounds. A female produces one calf every couple of years, after reaching sexual maturity at three to twelve years of age. Full body size maturity is usually attained at 25 to 30 years of age. Fin whales feed by filtering planktonic crustaceans, fish and squid through their baleen plates. Individuals can dive to depths of 230 metres and can stay submerged for about 15 minutes. The blow of a fin whale reaches six metres in height and manifests as a slim cone shape.

Contents

Physical Description

Balaenoptera physalus is a baleen whale which can be recognised as such by (i) the plates of baleen (rather than teeth) suspended from the upper jaw and (ii) the twin blowholes on the upper body. Like other rorquals, fin whales have accordion-like pleats of skin under the eye that let them expand the throat and mouth while filling it with water and prey, which are most often krill and small schooling fish. The ventral pleats extend beyond the navel. Key physical features of the Fin Whale are: endothermism, homoiothermism and bilateral symmetry

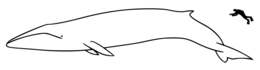

Fin Whales are the second largest mammals on Earth, after Blue Whales. The Fin Whale is slender bodied and can reach up to 24 m in length.The largest recorded Fin Whale was a female about 27 m long, weighing more than 100 tons. Size varies geographically: southern hemisphere whales are roughly 20 meters long, while northern and Arctic Fin whales reach up to 25 metres in length. Sexual dimorphism in Fin Whales is limited, with males and females reaching roughly the same size and weight as adults.

The relatively small flippers are less than one-fifth of the body length. The white underside wraps around the midsection laterally. The curved dorsal fin is 50 centimetres in height, and found relatively far back on the posterior.

These whales have two blowholes, and a single longitudinal ridge extends from the tip of the snout to the foreward edge of the blowholes. The head is pointed and V-shaped, the dorsal fin is a moderate size and set less far back on the body, and the head colouration is asymmetrical. The Fin Whale has a dark dorsal and lateral colouration with light streaks and the belly is white.

The left side of the head is grey, while much of the right side is white in colour.The Fin Whale can be confused with the Blue Whale, Balaenoptera musculus, but can be recognised by the pointed and V-shaped head with an asymmetrical colouration and the moderate sized dorsal fin that is set less far back on the body. The base of the tail is raised, causing the back to have a distinctive ridge.

Key distinguishing characteristics of the Fin Whale are:

- White lower jaw on right, gray on left

- Blow readily visible, manifesting as a ten metre high straight vertical column

- Curved dorsal fin close to tail

- Colouration: light grey with white belly, with occasional blotches of orange/yellow

- Blaze or chevron extending from eye across back

- Fin and Blue Whales have the deepest, loudest voices in the ocean, letting them communicate over great distances

- Second largest living animal after the Blue Whale.

Behaviour

Fin whales are among the most sociable species of whales, often congregating in family groups of between six and ten members. Occasionally Fin whales form groups of nearly 250 individuals in feeding grounds or during migration periods. Fin whales are highly migratory; in spring and early summer typically residing in colder feeding waters; in fall and winter, they return to warmer waters for mating.

Fin whales have long been noted for their extremely high speed and are one of the fastest [[marine mammal]s], with a cruising speed of nearly 23 mph and a “sprinting” speed of above 25 mph. Fin whales occassionally breech but when diving, rarely show the tail flukes. Fin whales can attain a diving depth of roughly 250 metres and remain underwater for nearly 15 minutes.

In addition, male fin whales often produce extremely low frequency sounds that are among the lowest sounds made by any animal. ("Balaenoptera physalus", 2008; Jefferson, Leatherwood, and Webber, 1994)

Voice and Sound Production

Fin whales, like Blue whales, communicate through vocalizations. Fin whales produce low frequency sounds that range from 16 to 40 Hertz (Hz), below the frequencies detected by humans. They also produce 20 Hz pulses (both single and patterned pulses), ragged low-frequency pluses and rumbles, and non-vocal sharp impulse sounds. Single frequencies (non-patterned pulses) last between one and two minutes, while patterned calling can persist for up to 15 minutes. The patterned pulses may be repeated for many days. (Finback Whales and Bioacoustics Research Program, 2006; Gambell, 1985; McDonlad, Hildebrand, and Webb, 1995)

Higher frequency sounds have been recorded and are thought to be used for communications between nearby Fin whales in other pods. These high frequencies may communicate information about local food availability. The 20 Hz single pulses help whales communicate with both local and long distances members, and patterned 20 Hz pulses are associated with courtship displays. (Gambell, 1985; McDonlad, Hildebrand, and Webb, 1995)

A study conducted on sound frequencies of Fin whales suggest that whales use counter-calling in order to derive information about their surroundings. Counter-calling is when a whale of one pod calls, and an answer is received from another pod. The information conveyed by the time it takes to answer as well as the echo pattern of the answer is believed to hold important information about the whale’s surroundings. (Gambell, 1985; McDonlad, Hildebrand, and Webb, 1995) Choruses of Fin whale calls are also observed. Acoustic vocalisations are only one form of whale communication channels; other perception channels of communication are visual, tactile, ultrasound and chemical.

Reproduction

The Fin whale's key reproductive characteristics include:

- Iteroparous

- Seasonal breeding

- Gonochoric/gonochoristic/dioecious (sexes separate)

- Sexual fertilization

- Viviparous births

Fin whales are seen in pairs during the breeding season and are thought to be monogamous. Courtship behaviour has been studied during the breeding season; typically a male will chase a female while emitting a series of repetitive, low-frequency vocalizations, similar to Humpback whale songs. However, these songs are not as complex as those observed in Humpback or Gray whales. One study has shown that only males produce these low-frequency sounds. Low frequencies are used because they travel efficienctly in water, attracting females from considerable distances. This is important since Fin whales do not have specific mating grounds and must communicate to find a member of the opposite sex. (Croll et al., 2002; Nowak, 1991; Sokolov and Arsen'ev, 1984)

Both mating and calving occur in the late fall or winter when Fin whales inhabit warmer waters: from November to January in the northern hemisphere and June to September in the southern hemisphere.

The female gives birth every two to three years, birthing one calf per pregnancy. Although there have been reports of Fin whales giving birth to multiple offspring, such a phenomenon is rare, and multiple offspring rarely survive. The gestation period is 11.0 to 11.5 months. After giving birth, the mother then undergoes a resting period of five or six months before mating again. This resting period may extend to a year if the female fails to conceive early in the mating period. (Gambell, 1985; Nowak, 1991; Reeves et al., 2002) Fin whale calves are born at an average length of six metres and having a body mass of 3500 to 3600 kilograms. Calves are precocial at birth, being able to swim immediately.

The mother nurses the infant for six to seven months after birth. Since the calf does not have the ability to suckle like land mammals, the mother must spray the milk into the mouth of the baby by contracting the circular muscles at the base of the nipple sinus. Feeding takes place at eight to ten minute intervals throughout the day. The calf is usually 14 metres (m) long at weaning, who then travels with the mother to a polar feeding area where it learns to feed itself independently. (Nowak, 1991; Sokolov and Arsen'ev, 1984)

The age of sexual maturity ranges from four to eight years. Male fin whales become sexually mature at a body length of about 18.6 m while females mature at a body length of 19.9 m. Full growth physical maturity does not occur until the whales have reached their ultimate length, after 22 to 25 years of age. The average length for a physically mature male is 18.9 m, and 20.1 m for females. (Sokolov and Arsen'ev, 1984; Tinker, 1988) The female Fin whale breeds every two to three years.

Lifespan/Longevity

The typical lifespan of a Fin whale is roughly 75 years, but some there are reports of fin whales that have lived in excess of 100 years. ("Balaenoptera physalus", 2008) Maximum longevity in the wild has been reported as 114 years. As in other whales, these animals attain sexual maturity before they are fully grown. It is estimated that they attain full body size physical maturity in about 25-30 years. (Ronald Nowak 1999).

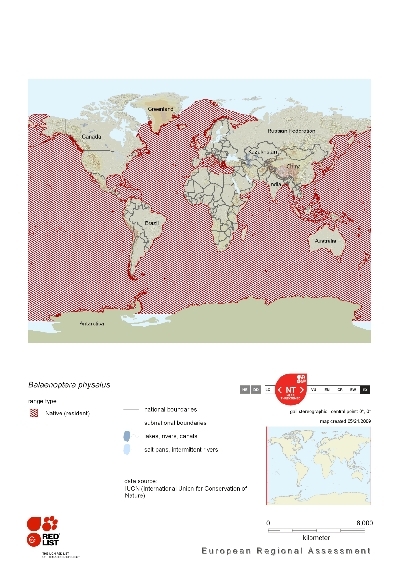

Distribution and Movements

Fin whales, or fin-backed whales, are found in all major oceans and open seas. Some populations are migratory, moving into colder waters during the spring and summer months to feed. In autumn, they return to temperate or tropical oceans. Because of the difference in seasons in the northern and southern hemisphere, northern and southern populations of fin whales do not meet at the equator at the same time during the year. Other populations are somewhat stationary, remaining in the same general area throughout the year. Non-migratory populations are found in the Mediterranean Sea and the Gulf of California. (Gambell, 1985; Jefferson, Leatherwood, and Webber, 1994; Nowak, 1991)

Fin whales, or fin-backed whales, are found in all major oceans and open seas. Some populations are migratory, moving into colder waters during the spring and summer months to feed. In autumn, they return to temperate or tropical oceans. Because of the difference in seasons in the northern and southern hemisphere, northern and southern populations of fin whales do not meet at the equator at the same time during the year. Other populations are somewhat stationary, remaining in the same general area throughout the year. Non-migratory populations are found in the Mediterranean Sea and the Gulf of California. (Gambell, 1985; Jefferson, Leatherwood, and Webber, 1994; Nowak, 1991)

In summer in the North Pacific Ocean, Fin whales migrate to the Chukchi Sea, the Gulf of Alaska and coastal California. In the winter, they are found from California to the Sea of Japan, East China and Yellow Seas, and into the Philippine Sea. (Gambell, 1985)

During the summer in the North Atlantic Ocean, Fin whales are found from the North American coast to Arctic waters around Greenland, Iceland, north Norway, and into the Barents Sea. In the winter these fin whale populations are found from the ice edge toward the Caribbean and the Gulf of Mexico and from southern Norway to Spain. (Gambell, 1985)

In the southern hemisphere, fin whales enter and leave the Antarctic throughout the year. Larger and older whales tend to travel further south than younger ones. (Gambell, 1985)

Habitat

Fin whales inhabit the temperate and polar zones of all major oceans and open seas and, less commonly, in tropical oceans and seas. They tend to live in coastal and shelf waters but never in water less than 200 meters deep. (Jefferson, Leatherwood, and Webber, 1994; Nowak, 1991; Reeves et al., 2002)

Food and Feeding Habits

Fin whales are able to expand their mouths and throats during feeding because of the approximately 100 pleats that run from the bottom of their bodies to their mouths. These pleats allow the mouth cavity to engulf water and pley during feeding. Fin whales are filter feeders, with between 350 and 400 baleen plates that are used to catch very small to medium-sized aquatic life suspended in the water. ("Balaenoptera physalus", 2008; Croll et al., 2002; Reeves et al., 2002)

Unlike other baleen whales, Fin whales lunge-feed instead of skimming, by accelerating quickly and turning or rolling into a vast school of prey. Then they contract the throat folds, forcing the water out through the fringed baleen plates and leaving food in the mouth. One of the unexplained oddities of the fin whale is color asymmetry: the lower jaw is white on the right side, black on the left. Some believe this is somehow a feeding adaptation.

Fin whales primarily feed on plankton-sized animals including crustaceans, fish and squid. As filter feeders, they passively consume food by filtering prey out of the water that they swim through. Fin whales occasionally swim around schools of fish to condense the school so that they increase their catch per dive. ("Balaenoptera physalus", 2008; Jefferson, Leatherwood, and Webber, 1994)

Animal prey consumed include fish, aquatic crustaceans, other marine invertebrates and zooplankton. Plantlife consumed chiefly consists of phytoplankton. In either case the species foraging behavior is characterised as filter-feeding.

Threats and Conservation Status

The major threat to the survival of this species has historically been hunting; their blubber, oil and baleen are all highly prized. Between 1935 and 1965, over 30,000 individuals were killed every year.

In addition, Fin whales are often injured or killed in vessel collisions. This is especially true in the Mediterranean Sea where collisions are a significant source of fin whale mortality. Between 2000 and 2004, five fatal collisions with vessels were recorded off the east coast of the United States. Fishing gear also kills Fin whales in the process known as bycatch; entanglement results in at least one death per year. Fishing accidents killed four fin whales in the years 2000 to 2004. Finally, a study done on whale calls shows that human sound can impede or prevent mating. Since the whales use low frequency sounds to call to females, human interruption through sound waves, such as military sonar and seismic surveys can disrupt mating signals sent to the females. This potentially can result in mates not meeting and a reduction in birth rates. ("Balaenoptera physalus", 2008; Croll et al., 2002)

In order to assist populations of Fin whales recover worldwide, the International Whaling Commission has set a zero limit for fin whale catches in the North Pacific and southern hemisphere. The catch limit was passed in 1976 and continues by law today. Fin whale hunting ceased in the North Atlantic in 1990. There are some exceptions to the commission’s limitation, with a limited number of whales allowed to be caught and killed by aboriginal natives in Greenland. commercial catches resumed in Iceland in 2006 and a Japanese fleet began catching fin whales for supposed "scientific" purposes in 2005. ("Balaenoptera physalus", 2008)

Conservationists are worried, however, that these protection measures are a case of too little too late, the southern hemisphere is thought to support only 5000 Fin whales at present, and the northern seas hold just 2000 to 3000 individuals. It seems likely that the species may never recover from past over-exploitation, and, in fact, may have entered an extinction vortex.

IUCN Red List classifies the Fin whale as Endangered. The USA Federal Government lists this species as Endangered. The Fin whale is listed in CITES Appendix I.

References

- Balaenoptera physalus, Encyclopedia of Life (accessed February 20, 2011)

- IUCN Red List (June, 2008)

- Macdonald, D. (2001) The New Encyclopedia of Mammals. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- CITES (June, 2008)

- Animal Diversity Web (February, 2002)

- O'Corry-Crowe, G.M. (2002) Beluga whale. In: Perrin, W.F., Würsig, B. and Thewissen, J.G.M. Eds. Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals. Academic Press, London.

- Carwardine, M. (1995) Whales, dolphins and porpoises. Dorling Kindersley, London.

- MarineBio.org (June, 2008)

- Hebridean Whale and Dolphin Trust (June, 2008)

- Pesante, G., Zanardelli, M. and Panigada, S. (2000) Evidence of man-made injuries on Mediterranean fin whales. European Research on Cetaceans, 14: 192 - 193.

- Whale and Dolphin Conservation Society (February, 2002)

- International Whaling Commission (June, 2008)

- "Finback Whales, Bioacoustics Research Program" (On-line). Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Accessed April 09, 209

- 2008. "Balaenoptera physalus" (On-line). ICUN 2008 Red List. Accessed April 02, 2009

- Bruyns, W.F.J.M., (1971). Field guide of whales and dolphins. Amsterdam: Publishing Company Tors.

- Howson, C.M. & Picton, B.E. (ed.), (1997). The species directory of the marine fauna and flora of the British Isles and surrounding seas. Belfast: Ulster Museum. Museum publication, no. 276.

- Jefferson, T.A., Leatherwood, S. & Webber, M.A., (1994). FAO species identification guide. Marine mammals of the world. Rome: United Nations Environment Programme, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

- Kinze, C. C., (2002). Photographic Guide to the Marine Mammals of the North Atlantic. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- OBIS, (2008). Ocean Biogeographic Information System.(access 2008-10-31)

- Reid. J.B., Evans. P.G.H., Northridge. S.P. (ed.), (2003). Atlas of Cetacean Distribution in North-west European Waters. Peterborough: Joint Nature Conservation Committee.

- Smith, T.D. (ed.), (2008). World Whaling Database: Individual Whale Catches, North Atlantic. In: M.G Barnard & J.H Nicholls, HMAP Data Pages. (accessed 2008-03-13)

- Attenborough, David. 1979. Life on Earth. Boston, MA: Little, Brown and Company. 319 p.

- Banks, R. C., R. W. McDiarmid, A. L. Gardner, and W. C. Starnes. 2003. Checklist of Vertebrates of the United States, the U.S. Territories, and Canada

- Banks, R. C., R. W. McDiarmid, and A. L. Gardner. 1987. Checklist of Vertebrates of the United States, the U.S. Territories, and Canada. Resource Publication, no. 166. 79

- Borges, P.A.V., Costa, A., Cunha, R., Gabriel, R., Gonçalves, V., Martins, A.F., Melo, I., Parente, M., Raposeiro, P., Rodrigues, P., Santos, R.S., Silva, L., Vieira, P. & Vieira, V. (Eds.) (2010). A list of the terrestrial and marine biota from the Azores. Princípia, Oeiras, 432 pp.

- Croll, D., C. Clark, A. Acevedo, B. Tershy, S. Flores, J. Gedamke, J. Urban. 2002. Only Male Fin Whales Sing Loud Songs. Nature, 117: 809. Accessed April 09, 2009

- Felder, D.L. and D.K. Camp (eds.), Gulf of Mexico–Origins, Waters, and Biota. Biodiversity. Texas A&M Press, College Station, Texas.

- Gambell, R. 1985. Fin Whale, Balaenoptera physalus. Pp. 171-192 in S. Ridgway, R. Harrison, eds. Handbook of Marine Mammals, Vol. 3, first Edition. San Diego, CA: Academic Press Inc.

- Gordon, D. (Ed.) (2009). New Zealand Inventory of Biodiversity. Volume One: Kingdom Animalia. 584 pp

- IUCN (2008) Cetacean update of the 2008 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.

- IUCN Red Book, NMFS/NOAA Technical Memo

- Jan Haelters

- Jefferson, T., S. Leatherwood, M. Webber. 1994. Marine Mammals of the World. Rome, Italy: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

- Jefferson, T.A., S. Leatherwood and M.A. Webber. 1993. Marine mammals of the world. FAO Species Identification Guide. Rome. 312 p.

- Keller, R.W., S. Leatherwood & S.J. Holt (1982). Indian Ocean Cetacean Survey, Seychelle Islands, April to June 1980. Rep. Int. Whal. Commn 32, 503-513.

- Koukouras, Athanasios (2010). check-list of marine species from Greece. Aristotle University of Thessaloniki. Assembled in the framework of the EU FP7 PESI project.

- Linnaeus, C., 1758. Systema Naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classis, ordines, genera, species cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Tenth Edition, Laurentii Salvii, Stockholm, 1:75, 824 pp.

- MEDIN (2011). UK checklist of marine species derived from the applications Marine Recorder and UNICORN, version 1.0.

- McDonlad, M., J. Hildebrand, S. Webb. 1995. Blue and Fin Whales Observed on Seafloor Array in the Northeast Pacific. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 98/2: 712-721.

- Mead, James G., and Robert L. Brownell, Jr. / Wilson, Don E., and DeeAnn M. Reeder, eds. 2005. Order Cetacea. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference, 3rd ed., vol. 1. 723-743

- Müller, Y. (2004). Faune et flore du littoral du Nord, du Pas-de-Calais et de la Belgique: inventaire. Fauna and flora of the Nord, Pas-de-Calais and Belgium: inventory. Commission Régionale de Biologie Région Nord Pas-de-Calais: France. 307 pp.

- North-West Atlantic Ocean species (NWARMS)

- Nowak, R. 1991. Balaenopteridae: Roquals. Pp. 969-1044 in R. Nowak, ed. Walker's Mammals of the World, Vol. 2, Fifth Edition. Baltimore and London: The John Hopkins University Press.

- Perrin, W. (2011). Balaenoptera physalus (Linnaeus, 1758). In: Perrin, W.F. World Cetacea Database. Accessed through: Perrin, W.F. World Cetacea Database (accessed on 2011-02-05)

- Ramos, M. (ed.). 2010. IBERFAUNA. The Iberian Fauna Databank

- Reeves, R., B. Stewart, P. Clapham, J. Powell. 2002. Sea Mammals of the World. London: A&C Black

- Rice, Dale W. 1998. Marine Mammals of the World: Systematics and Distribution. Special Publications of the Society for Marine Mammals, no. 4. ix + 231

- Ronald Nowak (1999) Walker's Mammals of the World. Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore.

- Slijper, E.J. (1938). Die Sammlung rezenter Cetacea des Musée Royal d'Histoire Naturelle de Belgique Collection of recent Cetacea of the Musée Royal d'Histoire Naturelle de Belgique. Bull. Mus. royal d'Hist. Nat. Belg./Med. Kon. Natuurhist. Mus. Belg. 14(10): 1-33

- Sokolov, V., V. Arsen'ev. 1984. Baleen Whales. Moscow: Nauka Publishers.

- Tinker, S. 1988. Whales of the World. Honolulu, Hawaii: Bess Press Inc.

- UNESCO-IOC Register of Marine Organisms

- Wilson, Don E., and DeeAnn M. Reeder, eds. 1993. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference, 2nd ed., 3rd printing. xviii + 1207

- Wilson, Don E., and F. Russell Cole. 2000. Common Names of Mammals of the World. xiv + 204

- Wilson, Don E., and Sue Ruff, eds. 1999. The Smithsonian Book of North American Mammals. xxv + 750

- van der Land, J. (2001). Tetrapoda, in: Costello, M.J. et al. (Ed.) (2001). European register of marine species: a check-list of the marine species in Europe and a bibliography of guides to their identification. Collection Patrimoines Naturels, 50: pp. 375-376