Environmental threats to the Great Barrier Reef

Environmental threats to the Great Barrier Reef include water pollution, invasive species, mechanical breakage by overuse and ocean temperature changes. The Great Barrier Reefis the world’s largest coral reef system, composed of around 3000 individual reefs and 900 islands that stretch for 2600 kilometres (1616 miles) and cover an area of approximately 344,400 square kilometres (133,000 miles). Located off the coast of Queensland, in the northeastern region of Australia, the Great Barrier Reef is home to a wide variety of organisms. It has been named a World Heritage Site and one of the seven natural wonders of the world.

The environmental integrity of the reef has significantly declined over the past fifty years. Even though a large part of the reef is protected by the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park, ocean temperature changes. poor water quality, crown-of-thorn sea star, and other human activities threaten its existence. Further damage to the Reef poses a threat to the thousands of diverse species that are part of this ecosystem.

These impacts are also likely to have far-reaching consequences for the industries and communities that depend on the Reef. As the largest commercial activity in the region, tourism in the Great Barrier Reef generates over AU$5.1 billion annually (2005) with approximately two million people visiting the Great Barrier Reef each year. Fishing in the areas around the Great Barrier Reef is a AU$1 billion industry each year and employs about 2000 people.

Despite crucial measures taken to protect the Reef, a number of factors still threaten its existence. Ultimately, further decline in the Reef’s health could have severe social and ecological consequences.

Contents

Threats

Coral reefs face many pressures, some arising naturally in the environment and some the result of human activities. According to the Australian Institute of Marine Science, threats to Australia’s coral reefs fall into three categories:

- Climate change

- Natural stresses

- Direct human pressures

Research suggests that many threats are closely linked and exacerbate each other.

Climate Change

One threat to the status of the Great Barrier Reef and of the planet's other tropical reef ecosystems is climate change, comprising chiefly of ocean temperature change and the El Nino effect.

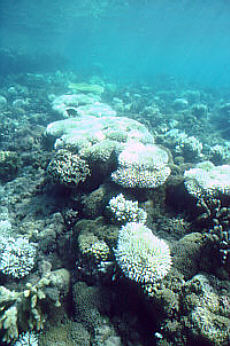

One of the greatest impacts of climate change has been the increase in frequency and severity of coral bleaching due to rising sea temperatures. Corals contain photosynthetic algae called zooxanthellae in their tissues. These algae provide the coral with food in return for protection in a symbiotic relationship and give the corals their distinctive color. Prolonged stressful environmental conditions cause a breakdown in this symbiotic relationship. These conditions include unusually high or low sea temperature, high or low light levels, freshwater or pollutants. As corals are stressed they lose the zooxanthellae from their tissues, leaving the white calcium carbonate skeleton visible through the coral tissue. This process is known as coral bleaching. The extent of coral bleaching is dependent on both above average temperatures and the length of time that the water temperature remains high. Bleached corals have the ability to recover as conditions return to normal, but if the conditions remain unfavorable for an extended time they will die. The threat to corals increases as the bleaching events become more frequent because they have no time to recover. Scientists predict that coral bleaching could become an annual occurrence with a continued rise in ocean temperatures, and this could have significant consequences for the Great Barrier Reef, as the rate at which the mass bleaching events occur is estimated to be much faster than reefs can recover from or adjust to.

Over the past decade, widespread coral bleaching has occurred on several distinct occasions, known as mass coral bleaching events. Three well-known events took place in 1997, 2002, and 2006.

- The summer of 1997-1998 was one of the hottest recorded on the Great Barrier Reef in the 20th Century. Mild bleaching began in late January and intensified by February/March. Extensive aerial surveys of 654 reefs conducted by scientists at the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority (GBRMPA) showed that 21% of offshore reefs had moderate to high levels of bleaching compared to 74% of inshore. Most reefs recovered fully with less than 5% of inshore reefs suffering high mortality. The worst affected reefs were in the Palm Island area where up to 70% of corals died.

- During the summer of 2002, a mass bleaching event occurred that was equivalent to or slightly more severe than the 1998 event. The first signs of substantial bleaching were reported in January, with the worst over by April. In response, GBRMPA implemented the world’s most comprehensive survey of coral bleaching in collaboration with AIMS, Cooperative Research Center for the Great Barrier Reef (CRC Reef) and National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Association (NOAA). Aerial surveys revealed bleaching in 54% of the 641 reefs observed. Nearly 41% of offshore and 72% of inshore reefs had moderate or high levels of bleaching. Again, reef recovery was generally good with less than 5% suffering high mortality. The worst affected reefs were in the Bowen area where around 70% of corals died.

- In January and February 2006, a further bleaching event took place on the southern end of the Great Barrier Reef, especially around the Keppel Islands. Surveys revealed that although bleaching was largely confined to this region, the extent of the bleaching in this area was even worse than in previous years, with up to 98% corals bleached on some reefs, resulting in nearly 39% mortality on the reef flats and 32% on the reef slopes.This event was compounded by a freak rain storm 8 months later that killed virtually all corals on the reef flat in the inner Keppel islands.

Climate alteration has implications for other forms of life on the Great Barrier Reef as well - some fish species preferred temperature range lead them to seek new areas to live, thus causing chick mortality in seabirds that prey on the fish. Also, for sea turtles, higher temperatures mean that the sex ratio of their populations will change, since the sex of sea turtles is determined by temperature. With seawater temperatures rising above sustainable levels for oceanic life, Australian marine ecology and biodiversity is suffering.

Natural Stresses

Crown-of-thorns Starfish

The crown-of-thorns starfish (COTS) is a coral reef predator which preys on coral polyps (tiny organisms that make up the reef) by climbing onto them, extruding its stomach over them, and releasing digestive enzymes to absorb the liquefied tissue. Under certain conditions, COTS can multiply; large outbreaks of these starfish, defined by the CRC Research Center as 30 adult starfish in in area of one hectare, can devastate reefs. An individual adult of this species can decimate up to six square meters of living reef in a single year.

In the past 40 years, three major COTS outbreaks have had a major impact on many reefs of the Great Barrier Reef (GBR). For example, in 2000, an outbreak contributed to a loss of 66 percent of live coral cover on sampled reefs in a study by the CRC Reefs Research Center. Researchers at the Australian Institute of Marine Science say COTS outbreaks are responsible for a greater decline in coral cover than any other threat to the GBR.

Overpopulation of crown-of-thorns has been blamed for widespread reef destruction and the starfish has been described as one of the most influential species in the diverse biotic communities that make up tropical coral reefs. Although large outbreaks of these starfish occur in natural cycles, human activity such as overfishing of its natural predators, like the Giant Triton, also contribute to an increase in the number of crown-of-thorns starfish.

Increasing outbreaks are also thought to be caused by possible environmental pollution triggers. Agricultural runoff (Surface runoff) may supply predators of crown-of-starfish larvae with plentiful alternative food sources. These explanations may also explain why massive outbreaks seemingly appear out of nowhere with no previous indication of an increasing population at the affected site. Other factors negatively affecting the reef ecosystem, such as coral bleaching, mean that outbreaks of the crown-of-thorns can now cause permanent and devastating damage.

Human Pressures

Water Quality

There are several water quality variables that affect coral reef health, including water temperature, salinity, nutrients, and suspended sediment concentrations. The species in the Great Barrier Reef area are adapted to tolerable variations in water quality. However, when critical thresholds are exceeded, they may be adversely impacted.

Unlike most reef environments, the Great Barrier Reef water catchment area is home to industrialized urban areas, and extensive areas of coastal land have been used for agricultural purposes. Runoff resulting from land-based agricultural activities is the primary influence on water quality in the Great Barrier Reef. Over the last 140 years, increased soil erosion has resulted in a three to four-fold increase in the export of sediment loads into the Great Barrier Reef environment. Due to agricultural expansion and the use of fertilizers, reef waters experience an increase in nutrients as well as a reduction in coral growth. Agricultural run-off also affects the relative abundance and composition of corals in inshore areas. Scientists at the Australian Institute of Marine Science estimate that average yearly inputs of nitrogen from the land have nearly doubled from 23,000 to 43,000 tons over the last past 150 years, while phosphorus inputs have almost tripled from 2400 tons to 7100 tons. In wet years, these inputs can be many times higher.

Water pollution is currently one of the principal threats to the Reef’s health. The rivers of northeastern Australia provide significant pollution of the Reef during tropical flood events with over 90 percent of this pollution coming from farms. Farm run-off is polluted as a results of overgrazing and excessive fertilizer and pesticide use. Mud pollution has increased by 800 percent and inorganic nitrogen pollution by 3000 percent since the introduction of European farming practices on the Australian landscape.

?Research carried out over almost 30 years by several groups suggests the increased sediment and nutrient loads now carried by runoff have multiple impacts, ranging from smothering inshore corals under layers of silt, to reducing the light which is essential for the growth of corals and seagrass, and allowing the growth of reef algae which can displace corals. Added to this is a slow trickle of toxic chemicals from agricultural, industrial and domestic activity which can weaken the health and resilience of corals and other organisms, making them more susceptible to disease outbreaks or climate impacts. Pollution has also been linked to intensified outbreaks of the coral-eating crown-of-thorns starfish.

Shipping

Australian coastal waters are at risk from pollution (Water pollution) due to both normal ship operations and shipping accidents. Waste and foreign species discharged in ballast water from ships (when proper waste disposal procedures are not followed) are a biological hazard to the Great Barrier Reef as it introduces harmful marine pests. Toxic compounds such as Tributyltin (TBT), found in some anti-fouling paints on ship hulls, are also released into the seawater and pose a danger to marine organisms and humans.

Shipping accidents are also a pressing concern due to the potential destruction and pollution caused by vessel groundings and oil spills. Several commercial shipping routes pass through the Great Barrier Reef and the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority estimates that about 6000 vessels greater than 50 metres (164 feet) in length use these routes each year. Although accidents are not highly frequent, they can have profound effects on the coral reefs. From 1985-2001, there were eleven collisions and twenty groundings on the inner GBR shipping route, with the leading cause of these collisions being human error.

Overfishing

Overfishing is one driving pressure that has had negative impacts on the Great Barrier Reef. Overfishing in the reef has caused a shift in the reef ecosystem and hurt the coral, sometimes beyond repair. Direct over-exploitation of different fishes and invertebrates by recreational, subsistence, and commercial fisheries results in the rapid decline in certain species’ populations. This in turn creates an imbalance in the predator-prey cycles that increases the number of predators for corals. Overfishing of herbivore (Herbivore) populations can cause algal growths on reefs. Ultimately, the reef’s ecological balance and biodiversity is negatively effected due to overfishing.

Fishing also impacts the reef through increased marine pollution from boats, bycatch of unintended species (such as dolphins and marine turtles) and reef habitat destruction from trawling, anchors and nets. Research suggests that the over-exploitation of marine organisms contributes to the degradation of the coral reef ecosystem as a whole.

Tourism/Recreation

An estimated 2.1 million recreational tourists visit the Great Barrier Reef each year. Some major types of marine tourism impact include coastal tourism development, tourism infrastructure (both island- and marine-based), boat-induced damage, water-based activities, and wildlife interactions.

The construction of tourism developments has had severe effects on catchment water quality and has resulted in vegetation damage, loss of wildlife habitat, and sediment runoff.

Boats cause harm to the Reef by anchoring, littering, and discharging waste, and they create the risk for oil or chemical spills which can damage the corals. Speeding vessels also kill, injure, and disturb wildlife.

Water-based activities such as diving, snorkeling, and fishing are popular among tourists. Unfortunately, these activities pose a great threat to the health of the Reef; they can cause local damage to fragile corals and coral breakage. High levels of diving activity at a single site can cause detectable changes to coral communities, and eventually, a change to the aesthetics of the reef if diving intensity is high enough. Reef walking can also result in damages to the Reef as people walk across the corals, causing disturbance and breakage.

Other human activities also effect the wildlife around the Great Barrier Reef. For example, whale watching creates the potential for whales to be disturbed by uncontrolled contacts. Fish feeding by divers can alter the diet of many fishes and lead to dependency. Close contact with seabirds can damage nesting sites and breeding. In addition, uncontrolled access during turtle-watching can effect the species’ breeding success.

Response

Protected Areas

The Great Barrier Reef Marine Park protects a large part of the Reef from damaging activities. Day-to-day management of the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park is conducted by the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority in cooperation with Queensland agencies and other Australian Government agencies. On July 1, 2004, it became the largest protected sea area in the world when the Australian Government increased the areas protected from extractive activities from 4.6% to 33.3% of the park. For example, fishing and the removal of artifacts or wildlife is strictly regulated in this area. In addition, commercial shipping traffic must stick to certain specific defined shipping routes that avoid the most sensitive areas of the park

Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority

The Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority (GBRMPA) is the principal adviser to the Australian Government on the control, care and development of the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park. It is structured into five groups to focus on the major issues relating to the Great Barrier Reef:

- Fisheries

- Tourism and Recreation

- Water Quality and Coastal Development

- Conservation, Heritage, and Indigenous Conservations

- Climate Change

The GBRMPA is responsible for the management of the Marine Park and undertakes a variety of activities including:

- Developing and implementing zoning and management plans

- Environmental impact assessment and permitting of use

- Research, monitoring and interpreting data

- Providing information, educational services and marine environmental management advice

The Authority also provides assistance and services to members of the public and stakeholder groups in the following areas:

- Assessment and issue of permits to undertake commercial activities in the Marine Park

- Advice and assistance, both nationally and internationally, on marine environmental management

- Provision of information and educational resources related to the Reef

- Operation of Reef HQ Aquarium, the education center for the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park, which aims to enhance community understanding and appreciation of the Great Barrier Reef

Legislation

The following are laws enacted by the state of Queensland relevant to the Great Barrier Reef:

- Nature Conservation Act 1992

- Marine Parks Act 1982

- Fisheries Act 1994

- Queensland Nature Conservation (Wildlife) Regulation 1994

Several laws enacted on the national level include:

- Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Act 1975

- Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999

- National Strategy for Ecologically Sustainable Development

- National Strategy for the Conservation of Australia's Biological Diversity

- Australia’s Oceans Policy

- National Strategy for the Conservation of Australian Species and Communities Threatened with Extinction

International Conventions

Several international conventions have discussed the condition and protection of the Great Barrier Reef, such as:

- World Heritage Convention 1972

- Biodiversity Convention 1992

- Bonn Convention

- Ramsar Site

- CITES 1973

- MARPOL 1973

- JAMBA

- CAMBA

- FCCC 1992

Sources

- Bryant, Dirk, Lauretta Burke, John McManus, and Mark Spalding. Reefs at Risk: A Map-Based Indicator of Threats to the World’s Coral Reefs, World Resources Institute, 1996. 2007-2008 Annual Report Australian Government Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority, October 2008.

- France-Presse, Agence. Great Barrier Reef under serious threat, Cosmos Magazine, 4 September 2009.

- Harriott, Vicki J. Marine tourism impacts and their management on the Great Barrier Reef CRC Reef Research Centre Technical Report No. 46, 2001.

- Haynes, David and Kirsten Michalek-Wagner. Great Barrier Reef Water Quality: Current Issues. GBRMPA Marine Pollution Bulletin, September 2001.

- Haynes, David, JonBrodie, JaneWaterhouse, ZoeBainbridge, DebBass and BarryHart. Assessment of the Water Quality and Ecosystem Health of the Great Barrier Reef (Australia): Conceptual Models Springer Science and Business Media, September 2007.Shah, Anup. Coral Reefs, Global Issues, 4 September 2009.

- Starck, Walter. ‘Threats’ to the Great Barrier Reef, IPA Backgrounder Volume 17/1, May 2005.

- Williams, David. Review of Impacts of Terrestrial Run-off on the Great Barrier Reef World Heritage Area, CRC Reef Research Centre Ltd and Australian Institute of Marine Science, 2001.

- Australian Institute of Marine Science Accessed 20 October 2009.

- CRC Reef Research Centre Accessed 1 November 2009.

- Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority Accessed 14 November 2009.

- Great Barrier Reef @ nationalgeographic.com Accessed 14 November 2009.

- Great Barrier Reef: UNESCO World Heritage Centre Accessed 21 October 2009.

- WWF-Australia Accessed 21 October 2009.

- Australian Government: Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts Accessed 1 November 2009.

Further Reading

- Chadwick, Douglas H. Coral in Peril, National Geographic, January 1999.

- Chadwick, Douglas H. Kingdom of Coral: Australia’s Great Barrier Reef, National Geographic, January 2001.

- Veron, J.E.N. A Reef in time: the Great Barrier Reef from beginning to end. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2008.

- Well, Sue, and Nick Hann. The Greenpeace Book of Coral Reefs. Sterling Publishing Company, 1992.

Portions of this article were researched written by a student at Boston University participating in the Encyclopedia of Earth's Student Science Communication Project. The project encourages students in undergraduate and graduate programs to write about timely scientific issues under close faculty guidance. All articles have been reviewed by internal EoE editors, and by independent experts on each topic.