Ecosystems and Human Well-being Synthesis: Preface

This is part of the Millenium Ecosystem Assessment report Ecosystems and Human Well-Being Synthesis

The Millennium Ecosystem Assessment was carried out between 2001 and 2005 to assess the consequences of ecosystem change for human well-being and to establish the scientific basis for actions needed to enhance the conservation and sustainable use of ecosystems and their contributions to human well-being. The MA responds to government requests for information received through four international conventions—the Convention on Biological Diversity, the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification, the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands, and the Convention on Migratory Species—and is designed to also meet needs of other stakeholders, including the business community, the health sector, nongovernmental organizations, and indigenous peoples. The sub-global assessments also aimed to meet the needs of users in the regions where they were undertaken.

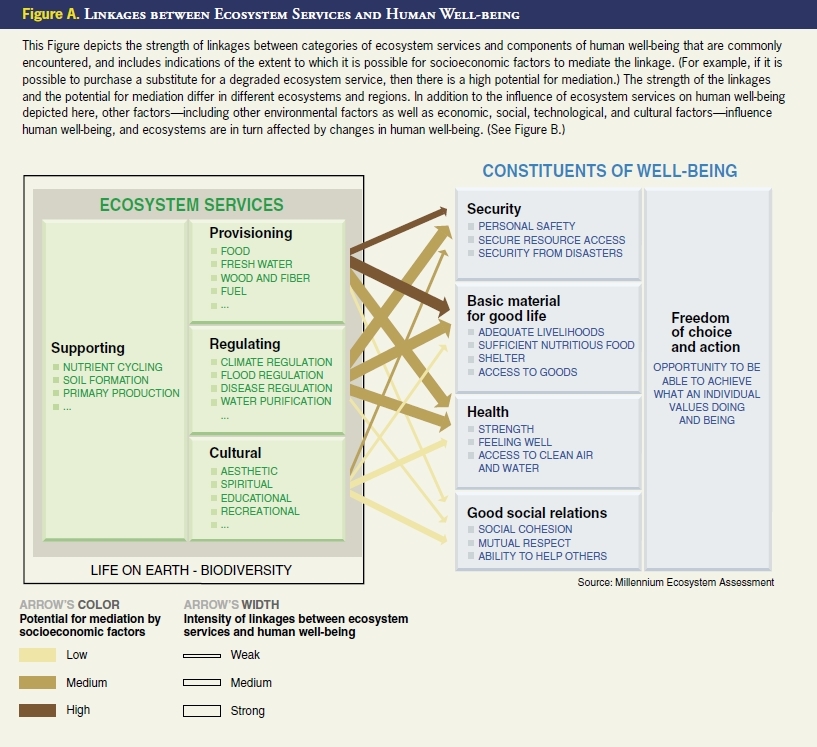

The assessment focuses on the linkages between ecosystems and human well-being and, in particular, on “ecosystem services.” An ecosystem is a dynamic complex of plant, animal, and microorganism communities and the nonliving environment interacting as a functional unit. The MA deals with the full range of ecosystems—from those relatively undisturbed, such as natural forests, to landscapes with mixed patterns of human use, to ecosystems intensively managed and modified by humans, such as agricultural land and urban areas. Ecosystem services are the benefits people obtain from ecosystems. These include provisioning services such as food, water, timber, and fiber; regulating services that affect climate, floods, disease, wastes, and water quality; cultural services that provide recreational, aesthetic, and spiritual benefits; and supporting services such as soil formation, photosynthesis, and nutrient cycling. (See Figure A.) The human species, while buffered against environmental changes by culture and technology, is fundamentally dependent on the flow of ecosystem services.

The MA examines how changes in ecosystem services influence human well-being. Human well-being is assumed to have multiple constituents, including the basic material for a good life, such as secure and adequate livelihoods, enough food at all times, shelter, clothing, and access to goods; health, including feeling well and having a healthy physical environment, such as clean air and access to clean water; good social relations, including social cohesion, mutual respect, and the ability to help others and provide for children; security, including secure access to natural and other resources, personal safety, and security from natural and human-made disasters; and freedom of choice and action, including the opportunity to achieve what an individual values doing and being. Freedom of choice and action is influenced by other constituents of well-being (as well as by other factors, notably education) and is also a precondition for achieving other components of well-being, particularly with respect to equity and fairness.

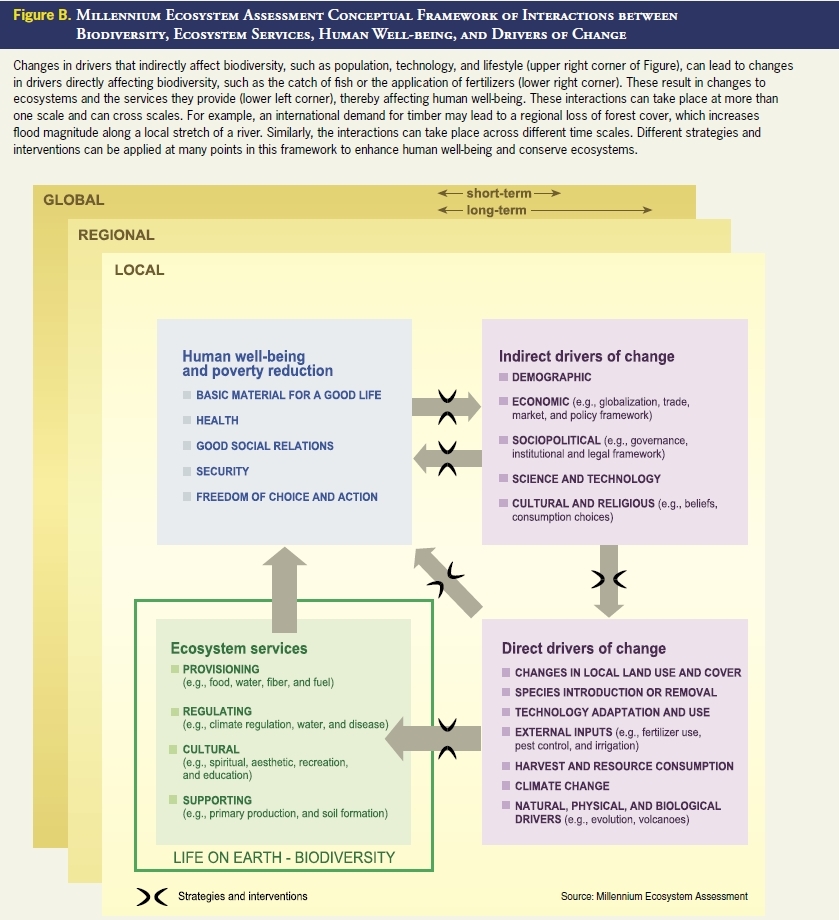

The conceptual framework for the MA posits that people are integral parts of ecosystems and that a dynamic interaction exists between them and other parts of ecosystems, with the changing human condition driving, both directly and indirectly, changes in ecosystems and thereby causing changes in human well-being. (See Figure B.) At the same time, social, economic, and cultural factors unrelated to ecosystems alter the human condition, and many natural forces influence ecosystems. Although the MA emphasizes the linkages between ecosystems and human well-being, it recognizes that the actions people take that influence ecosystems result not just from concern about human well-being but also from considerations of the intrinsic value of species and ecosystems. Intrinsic value is the value of something in and for itself, irrespective of its utility for someone else.

The Millennium Ecosystem Assessment synthesizes information from the scientific literature and relevant peer-reviewed datasets and models. It incorporates knowledge held by the private sector, practitioners, local communities, and indigenous peoples. The MA did not aim to generate new primary knowledge, but instead sought to add value to existing information by collating, evaluating, summarizing, interpreting, and communicating it in a useful form. Assessments like this one apply the judgment of experts to existing knowledge to provide scientifically credible answers to policy-relevant questions. The focus on policy-relevant questions and the explicit use of expert judgment distinguish this type of assessment from a scientific review.

Five overarching questions, along with more detailed lists of user needs developed through discussions with stakeholders or provided by governments through international conventions, guided the issues that were assessed:

- What are the current condition and trends of ecosystems, ecosystem services, and human well-being?

- What are plausible future changes in ecosystems and their ecosystem services and the consequent changes in human well-being?

- What can be done to enhance well-being and conserve ecosystems? What are the strengths and weaknesses of response options that can be considered to realize or avoid specific futures?

- What are the key uncertainties that hinder effective decision-making concerning ecosystems?

- What tools and methodologies developed and used in the MA can strengthen capacity to assess ecosystems, the services they provide, their impacts on human well-being, and the strengths and weaknesses of response options?

The MA was conducted as a multi-scale assessment, with interlinked assessments undertaken at local, watershed, national, regional, and global scales. A global ecosystem assessment cannot easily meet all the needs of decision-makers at national and sub-national scales because the management of any particular ecosystem must be tailored to the particular characteristics of that ecosystem and to the demands placed on it. However, an assessment focused only on a particular ecosystem or particular nation is insufficient because some processes are global and because local goods, services, matter, and energy are often transferred across regions. Each of the component assessments was guided by the MA conceptual framework and benefited from the presence of assessments undertaken at larger and smaller scales. The sub-global assessments were not intended to serve as representative samples of all ecosystems; rather, they were to meet the needs of decision-makers at the scales at which they were undertaken.

The work of the MA was conducted through four working groups, each of which prepared a report of its findings. At the global scale, the Condition and Trends Working Group assessed the state of knowledge on ecosystems, drivers of ecosystem change, ecosystem services, and associated human well-being around the year 2000. The assessment aimed to be comprehensive with regard to ecosystem services, but its coverage is not exhaustive. The Scenarios Working Group considered the possible evolution of ecosystem services during the twenty-first century by developing four global scenarios exploring plausible future changes in drivers, ecosystems, ecosystem services, and human well-being. The Responses Working Group examined the strengths and weaknesses of various response options that have been used to manage ecosystem services and identified promising opportunities for improving human well-being while conserving ecosystems. The report of the Sub-global Assessments Working Group contains lessons learned from the MA sub-global assessments. The first product of the MA—Ecosystems and Human Well-being: A Framework for Assessment, published in 2003—outlined the focus, conceptual basis, and methods used in the MA.

Approximately 1,360 experts from 95 countries were involved as authors of the assessment reports, as participants in the sub-global assessments, or as members of the Board of Review Editors. (See Appendix C for the list of coordinating lead authors, sub-global assessment coordinators, and review editors.) The latter group, which involved 80 experts, oversaw the scientific review of the MA reports by governments and experts and ensured that all review comments were appropriately addressed by the authors. All MA findings underwent two rounds of expert and governmental review. Review comments were received from approximately 850 individuals (of which roughly 250 were submitted by authors of other chapters in the MA), although in a number of cases (particularly in the case of governments and MA-affiliated scientific organizations), people submitted collated comments that had been prepared by a number of reviewers in their governments or institutions.

The MA was guided by a Board that included representatives of five international conventions, five U.N. agencies, international scientific organizations, governments, and leaders from the private sector, nongovernmental organizations, and indigenous groups. A 15-member Assessment Panel of leading social and natural scientists oversaw the technical work of the assessment, supported by a secretariat with offices in Europe, North America, South America, Asia, and Africa and coordinated by the United Nations Environment Programme.

The MA is intended to be used:

- to identify priorities for action;

- as a benchmark for future assessments;

- as a framework and source of tools for assessment, planning, and management;

- to gain foresight concerning the consequences of decisions affecting ecosystems;

- to identify response options to achieve human development and sustainability goals;

- to help build individual and institutional capacity to undertake integrated ecosystem assessments and act on the findings; and

- to guide future research.

Because of the broad scope of the MA and the complexity of the interactions between social and natural systems, it proved to be difficult to provide definitive information for some of the issues addressed in the MA. Relatively few ecosystem services have been the focus of research and monitoring (Environmental monitoring and assessment) and, as a consequence, research findings and data are often inadequate for a detailed global assessment. Moreover, the data and information that are available are generally related to either the characteristics of the ecological system or the characteristics of the social system, not to the all-important interactions between these systems. Finally, the scientific and assessment tools and models available to undertake a cross-scale integrated assessment and to project future changes in ecosystem services are only now being developed. Despite these challenges, the MA was able to provide considerable information relevant to most of the focal questions. And by identifying gaps in data and information that prevent policy-relevant questions from being answered, the assessment can help to guide research and monitoring that may allow those questions to be answered in future assessments.

Terms of Use

The copyright for material on this page is the property of the World Resources Institute. Click here for the Terms of Use (Ecosystems and Human Well-being Synthesis: Preface).

Disclaimer: This chapter is taken wholly from, or contains information that was originally written for the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment as published by the World Resources Institute. The content has not been modified by the Encyclopedia of Earth.

|

|