Economic change in Africa

Contents

- 1 Introduction Equitable and environmentally sustainable growth can improve human well-being and increase the range of opportunities available to people, including those who are most disadvantaged. Africa has experienced its best economic performance in many years. In 2004 Africa grew at 5.1 percent, up from 3.7 percent in 2003. Between 1990 and 2003, Africa’s economies grew at an average of 2.6 percent annually. This improved growth has had a mixed bag of consequences, increasing opportunities to meet key Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) (Economic change in Africa) targets and improving human well-being, which can have positive spin-offs for the environment as options increase. However, Sub Sahara Africa (SSA) must grow on average at 7 percent per year to reduce income poverty by half by 2015. Only six African countries, mostly in north Africa, are likely to meet the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) of halving the number of people living on less than a dollar a day. The MDGs remain underfinanced – by more than US$40,000 million overall. For more information, see Africa Environment Outlook 2, Annexes in the Further Reading section.

- 2 Production and consumption

- 3 Impacts of economic change on livelihoods and the environment

- 4 Further Reading

Introduction Equitable and environmentally sustainable growth can improve human well-being and increase the range of opportunities available to people, including those who are most disadvantaged. Africa has experienced its best economic performance in many years. In 2004 Africa grew at 5.1 percent, up from 3.7 percent in 2003. Between 1990 and 2003, Africa’s economies grew at an average of 2.6 percent annually. This improved growth has had a mixed bag of consequences, increasing opportunities to meet key Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) (Economic change in Africa) targets and improving human well-being, which can have positive spin-offs for the environment as options increase. However, Sub Sahara Africa (SSA) must grow on average at 7 percent per year to reduce income poverty by half by 2015. Only six African countries, mostly in north Africa, are likely to meet the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) of halving the number of people living on less than a dollar a day. The MDGs remain underfinanced – by more than US$40,000 million overall. For more information, see Africa Environment Outlook 2, Annexes in the Further Reading section.

There is considerable variation between the economic achievements of countries in the region – with prices of oil and metals, low cotton and cocoa prices, dollar depreciation and euro appreciation, the locust plague in the Sahel region, rainfall, corruption, and political conflict and instability being important contributing factors. Solid growth is expected to continue between 2005 and 2007 at an average rate of 4.7 percent as the effect of new oil fields in Central Africa wears off. The high level of vulnerability to external shocks (such as prices and the loss of preferential treatment), environmental factors such as weather conditions, and conflict make these key areas for policy focus and collaborative initiatives. This close relationship to the environment is indicative of the need for better environmental monitoring and, in particular, risk and disaster warning systems to support greater preparedness and more effective responses.

Production and consumption

Figure 1: Fisherman pulling their nets in Cape Verde.

Figure 1: Fisherman pulling their nets in Cape Verde.(Source: M. Marzot/FAO)

Changing production and consumption patterns, globally and in Africa, and the way in which growth is achieved have direct implications for African livelihoods and their sustainability.

Global economic policy dealing with tariffs, import quotas and crop subsidies has direct impacts on the livelihoods and opportunities of people in Africa.

At the national level, growth of the economy can result in both positive and negative effects on well-being and environmental resources. For example, economic expansion may provide new livelihood opportunities to more people through job creation as well as through diversifying livelihood options. Growth must be equitable and specifically focus on delivering benefits to poor people. However, growth may endanger the sustainability of livelihoods depending on how it is carried out with respect to environmental integrity. For instance, when fishing (Marine fisheries) is done in an unsustainable manner, short-run benefits will be accrued, but at the same time sustainability of catch will be impaired through depletion and, therefore, affect long-term benefits.

Although in 2000 Africa accounted for 13.6 percent of the world population, its gross domestic product (GDP) was just under 1.7 percent of the world’s GDP. For SSA, GDP per capita, using purchasing power parity (PPP), amounted to US$1,856 compared to the average for countries with high human development of US$25,665. This is significant for purchasing power, savings and investment growth rates as well as resources available to governments and individuals, making them more reliant on the natural resource base for their basic needs. The GDP per capita (PPP) across the region varies considerably, with Equatorial Guinea having an average GDP per capita of US$19,780, South Africa US$10,346 and Sudan US$1,910. Inequity within a particular country is clearly important for how this benefit is actually spread. Unequal growth remains a major challenge for Africa – income distribution is highly skewed, with 40 percent of the population receiving only 11 percent of income, while the richest 20 percent gets 58 percent of income. Income inequality is particularly evident across the urban-rural divide.

Export of natural resources remains a major factor in the economies of many countries. Instability and adverse price trends drive countries to exploit more resources to meet their domestic and foreign obligations, including debt servicing, at the expense of long-term sustainability of the resources.

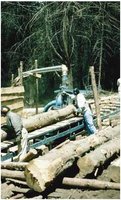

Figure 2: The use of mobile sawmills give SMEs the opportunity to add value to timber logs and to increase their earning potential. (Source: P. Reidar/CIFOR)

Figure 2: The use of mobile sawmills give SMEs the opportunity to add value to timber logs and to increase their earning potential. (Source: P. Reidar/CIFOR) Africa’s economies are more reliant on agriculture than those of any other region, with around 70 percent of Africans working in the agricultural sector. About three-fifths of African farmers are subsistence farmers tilling small plots of land to feed their families, with only a minimal surplus that can be sold. Although agriculture is a major employer, employing 56.5 percent of Africa’s total labor force, it contributes only 14 percent of GDP, while industry and services contributed 29 percent and 57 percent respectively. Also, agricultural productivity, in terms of value-added per agricultural worker in 1995 dollars, declined between 1988-90 and 2000-2002 periods from US$382 to US$360. This means that, with high dependency on agriculture and falling productivity at the same time, poverty is increasingly entrenched in rural Africa. The contribution of natural resources to GDP is often undervalued. See Africa Environment Outlook 2, Annexes in the Further Reading section for more information.

In terms of mining and drilling, Africa’s most valuable exports are its minerals and petroleum. These activities are concentrated in only a few countries. South Africa, Namibia, Botswana, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo have substantial reserves of gold, diamond and copper. Nigeria, Angola, Gabon, Libya, Algeria and others export significant amounts of petroleum. These areas make up the vast majority of mineral and petroleum exports from Africa. This has been the focal point for foreign direct investment (FDI) which has been driven primarily by developed countries’ needs. With respect to manufacturing, Africa is the world’s least industrialized region. Despite large local supplies of cheap labor, almost all of the region’s natural resources are exported elsewhere for secondary processing. The lack of value-adding activities means that the full potential from natural resources is not being earned within African countries. Only about 15 percent of employment is generated by the manufacturing sector. Industrial sector restructuring and reform measures have led to a collapse of industries in some countries and hence the declining share of manufacturing to total economy. While industrial development offers important opportunities, it also creates certain risks, particularly in the management of pollution and human health. There is evidence that developed countries are relocating their chemical industry to developing countries.

The 1980s and early 1990s witnessed serious economic decline or stagnation in most African countries. Agricultural productivity failed to keep pace with the growth of population and suffered particularly from falling productivity in the export sector and from declining markets and prices. Population growth rates in the period 1990-2003 were higher than the growth of GDP per capita in 2003 at 2.5 percent and 1.3 percent respectively. Food imports were and still are essential in most countries to maintain an adequate total food supply and, in certain cases, to keep food costs down. Debt has mounted and pressures on resource use have increased.

In response to the economic hardships of the 1980s, many African countries undertook programs of economic reform with guidance from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank. These reforms, spearheaded by the Structural Adjustment Programmes (SAPs), aimed at stabilizing the economies, liberalizing exchange rates, freeing the productive energies of the private sector and opening up to trade and investment. As the negative impacts of these policies were realized, new approaches to economic planning and development have been adopted, including the now widely used Poverty Reduction Strategies (PRS).

Impacts of economic change on livelihoods and the environment

Macroeconomic reforms in Africa, epitomized by the Structural Adjustment Programmes (SAPs), have had mixed impacts on the environment, mainly through the processes of livelihood diversification and increased human mobility.

A key response to the poor performance of the formal sector has been the diversification into and intensification of informal sector activities as people try to make ends meet. Many of these activities are based on natural resources and include carpentry and craft production, charcoal manufacturing, collection and trade of non-timber forest products (NTFPs), artisan mining and metal works. Although entry into many such activities is easy, their profitability and efficiency is undercut by bureaucratic controls, lack of investment and inadequate support for market engagement. There is little incentive for users to invest in technologies and to manage resources sustainably. Since the 1990s, there has been a growing focus on other livelihood activities that could more effectively combine conservation and development interests, such as ecotourism and community-based conservation initiatives.

Livelihood diversification has always played some part in providing a “pathway” out of poverty for poorer groups of people. Since the mid-1980s, it has become evident that livelihood diversification has increased as a response to economic and social changes. These changes have led to a saturated agricultural labor market, reduced access to common property and increased mobility. In general, these programs resulted in an increase in the number of people living in poverty and decreased access to social services, such as health and education.

Figure 3: Agriculture is an important economic activity for many urban dwellers. Urban farmers in Nairobi, Kenya. (Source: Urban Harvest CIP SSA)

Figure 3: Agriculture is an important economic activity for many urban dwellers. Urban farmers in Nairobi, Kenya. (Source: Urban Harvest CIP SSA) Within the agricultural sector, many rural dwellers have sought to intensify their agricultural activities. Pastoralists in Tanzania, for instance, have adopted crop cultivation to supplement livestock keeping. Other activities include trading in a range of products including milk, firewood, animals and honey; wage employment, both local and outside the area, including working as a hired herder, farm worker and migrant laborer; renting property; and gathering and selling wild products, such as gum arabic, firewood, game trophies, bushmeat, live animals or medicinal plants. Market failures and the need for consumer items have become an important force pushing pastoralists into diversification using wildlife, ecotourism and consumptive utilization.

As good as these activities are in sustaining household livelihoods in the short-run, if poorly managed they may have detrimental impacts on environmental resources. The indiscriminate felling of trees for agricultural expansion and timber products has laid watersheds bare, threatening the water catchment functions of forested watersheds. Pressure on water resources for various uses including domestic, livestock and industrial use, among others, has increased due to more extensive economic activities and population congestion in river basins, causing water (Society and water resources) allocation and use conflicts. Other alternative income activities, such as artisan mining, have also been affected by economic changes. Artisan mining in Africa has been in existence for centuries, but its magnitude has increased since the mid-1980s as a result of livelihood diversification strategies and opportunities created by trade liberalization. An estimated 20 million people depend on artisan mining in Africa. In a number of countries, including Mali, Tanzania, Ghana, South Africa, Zambia and Mozambique, the role of artisan mining in improving livelihood for rural poor communities has been recognized and has accordingly been factored into national planning strategies. Artisan mining has been a major source of income, increasing the wealth of rural populations. This new income supports investments in agriculture and nonagricultural pursuits, and thus increases the options available to rural communities. Inadequate regulation and enforcement in the artisan mining sector has, however, led to serious environmental problems and risk to humans. Toxic chemicals are sometimes used in the extraction of minerals, such as gold, which end up in the rivers. Toxins bioaccumulate in fish and wildlife, which are sources of food for the same communities. Other environmental problems include deforestation, soil erosion, silting of rivers, landslides and mining accidents. It is estimated that the rate of occurrence of fatal accidents in small mining activities is six times higher than it is in larger operations.

Migration as a livelihood diversification strategy is important in providing much needed resources for investment in rural production through remittances. In Ethiopia and Mali, for example, migration is widespread and in both countries it is linked to income generation strategies. This is also the case for many countries in Southern Africa. Migration may represent a rational allocation of total household labor to maximize household utility. In some communities, an increasing scarcity of traditional male labor, due to migration, has also promoted new roles for the women left behind. These women become the main decision-makers, particularly within the [[agricultural] sector]. The gendered division of family labor has in some instances changed as a result of the loss of male employment through urban job retrenchment, forcing women to seek additional income-generating activities to support the family. The consequence has been that problems induced by environmental degradation, such as deforestation or declines in water quality, have far-reaching consequences on entire families as time spent on looking for wood or water directly affects household incomes. Various policy responses seek to address these problems. Currently, several African countries are involved in the World Bank-initiated Poverty Reduction Strategies (PRS), whose second phase includes the environment as an important aspect of poverty reduction.

Further Reading

- Adepoju, A., 2004. Changing configurations of migration in Africa. Migration Policy Institute.

- AfDB, 2004. Africa Development Report 2004: Africa in the Global Trading System. African Development Bank/Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- Barrett, C. B., Bezuneh, M. and Aboud,A., 2001. Income diversification, poverty traps and policy shocks in Cote d’Ivoire and Kenya. Food Policy 26(4), 367-84.

- Bigsten, A., 1996. The circular migration of smallholders in Kenya. Journal of African Economies, 5(1), 1-20.

- FAO, 2003. Forestry Outlook Study for Africa – African Forests: A view to 2020. African Development Bank, European Commission and the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome.

- FAO, 2004. FAOSTAT on-line statistical service. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome.

- Gilman, J., 1999. Artisanal mining and sustainable livelihoods. SL Strategy Papers. United Nations Development Programme.

- Griffin, K. (1976). On the emigration of the peasantry. World Development, 4, 353-61.

- Henriot, P. J., 1998. global.html Globalization: implications for Africa.

- IOM (2005a). The Millennium Development Goals and Migration. IOM Migration Research Series No 20.

- IOM (2005b). World Migration 2005: Costs and Benefits of International Migration. International Organization for Migration, Geneva.

- McDowell, C. and de Haan, A., 1997. Migration and Sustainable Livelihoods: A Critical Review of the Literature. IDS Working Paper 65, Institute of Development Studies, Brighton.

- OECD Development Centre and AfDB, 2003. African Economic Outlook 2002/2003. Development Centre of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development and the African Development Bank. Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, Paris.

- OECD Development Centre and AfDB, 2005. African Economic Outlook 2004/2005. Development Centre of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development and the African Development Bank. Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, Paris.

- UNDP, 2005. Human Development Report 2005: International cooperation at a crossroads – Aid, trade and security in an unequal world. United Nations Development Programme, New York.

- World Bank (2005b). World Development Report 2006: Equity and Development. The World Bank and Oxford University Press, New York.

- WRI in collaboration with UNEP, UNDP and the World Bank (2005). World Resources 2005: The Wealth of the Poor – Managing Ecosystems to Fight Poverty. World Resources Institute, Washington, D.C.

| Disclaimer: This article is taken wholly from, or contains information that was originally published by, the United Nations Environment Programme. Topic editors and authors for the Encyclopedia of Earth may have edited its content or added new information. The use of information from the United Nations Environment Programme should not be construed as support for or endorsement by that organization for any new information added by EoE personnel, or for any editing of the original content. |