East Bering Sea large marine ecosystem

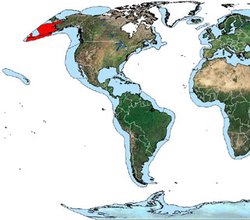

Location of the East Bering Sea Large Marine Ecosystem. (Source: NOAA)

Location of the East Bering Sea Large Marine Ecosystem. (Source: NOAA) The East Bering Sea large marine ecosystem (LME) is characterized by its Sub-Arctic climate and high primary productivity. It is customary to divide the ecological analysis of the Bering Sea into east and west elements; the counterpart to this marine ecosystem being the West Bering Sea large marine ecosystem. Important hypotheses concerned with the growing impacts of water pollution, overfishing, and environmental changes on sustained biomass yields are under investigation. LME book chapters and articles pertaining to this LME include Incze and Schumacher (1986), Carleton Ray and Hayden (1993), Livingston et al. (1999), and Schumacher et al. (2003). The East Bering Sea Large Marine Ecosystem is bounded by the Bering Strait on the north, by the Alaskan Peninsula and Aleutian island chain on the south, and by the Alaskan coast on the east. The LME is characterized by a wide shelf and by a seasonal ice cover that reaches its maximum extent of 80% coverage in March.

Contents

- 1 Productivity

- 2 Fish and Fisheries

- 3 Pollution and Ecosystem Health

- 4 Socio-economic Conditions

- 5 Governance

- 6 Articles and LME Volumes G. Carleton Ray and Bruce P. Hayden, 1993. Marine biogeographic provinces of the Bering, Chukchi and Beaufort seas. In: Large Marine Ecosystems: stress, mitigation and sustainability, edited by K. Sherman, LM Alexander and B.D. Gold, 1993. ISBN: 087168506X (East Bering Sea large marine ecosystem) . * EPA, 2001. National Coastal Condition Report. * FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO)), 2003. Trends in oceanic captures and clustering of large marine ecosystems: 2 studies based on the FAO capture database. FAO fisheries technical paper 435. 71 pages. * Incze, Lewis and J.D. Schumacher. 1986. "Variability of the Environment and Selected Fisheries Resources of the Eastern Bering Sea Ecosystem." In Kenneth Sherman and Lewis M. Alexander (eds.), Variability and Management of Large Marine Ecosystems (Boulder: Westview). AAAS Selected Symposium 99. ISBN: 0813371457. * Livingston, P.A., L-L. Low, and R.J. Marasco. 1999. "Eastern Bering Sea Ecosystem Trends." in Kenneth Sherman and Qisheng Tang (eds), Large Marine Ecosystems of the Pacific Rim: Assessment, Sustainability, and Management. (Blackwell Science) pp. 140-162. ISBN: 0632043369. * J.D Schumacher, N.A. Bond, R.D. Brodeur, P.A. Livington, J.M. Napp and P.J. Stabeno, 2003. Climate Change in the Southeastern Bering Sea and some consequences for its biota (volume in press).

- 7 Other References

Productivity

Temperature, currents and seasonal oscillations influence the productivity of this LME. The Eastern Bering Sea LME is considered a Class II, moderately high (150-300 grams of carbon per square meter per year) productivity ecosystem, based on SeaWiFS global primary productivity estimates. For information on primary and secondary productivity in the Eastern Bering Sea Large Marine Ecosystem, see the 1996 report from the Commission on Geosciences, Environment and Resources, and the segment on "Primary and Secondary Production." The LME is experiencing a change in species dominance and species abundance in some ecological groups, but it is difficult to establish the causal mechanisms responsible for inducing ecosystem change. There is still much to understand about the levels of natural variability in many of the species abundance, mainly because of the limited time series of unbiased observations. For more information on climate change in the Southeastern Bering Sea, and some consequences for its biota, see Schumacher et al., 2003.

Fish and Fisheries

Graph: East Bering Sea LME-1. (Source: NOAA)

Graph: East Bering Sea LME-1. (Source: NOAA) The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) 10-year capture trend (1990-1999) shows decreasing catches of all major species groups in recent years, with the only exceptions being diadromous fishes and crustaceans. The catch decreased from 2 million metric tons in 1990 to 1.5 million in 1999 (see FAO, 2003, figure 14 appendix 2). The Eastern Bering Sea Large Marine Ecosystem supports the world's largest pollock fishery (Fisheries and aquaculture). The harvest now stands at about 1 million metric tons. Other commercially valuable species include halibut, herring, capelin, Pacific cod, skate, flounder, Greenland turbot, sole, dab, plaice and crab. For a graph of catch biomass of pollock, other roundfish, flatfish and invertebrates in the Eastern Bering Sea from 1954 to 1998, see Schumacher et al., 2003. For crab and shrimp fisheries in the East Bering Sea, see Our Living Oceans (1999). For biomass trends of crab species from 1979 to 1993, and for finfish fishery exploitation rates compared with crab recruitment in this LME, see Livingston, Low and Marasco, 1999. An area targeted for pollock in this LME is the "Donut Hole" residing outside of the US and Russian exclusive economic zones. Historical catches here were too high in the late 1980s and not sustainable. The abundance of pollock in this area has greatly diminished (see Our Living Oceans, 1999). There is evidence of overexploitation, excessive by-catch, and destructive fishing practices, from the rise of industrial fishing and factory trawler operations. There is strong evidence of effective ecosystem-based management planning for this LME. The management regime annually updates fishing quotas based on biomass estimates, including those for Alaska pollock. Because of the Steller sea lion interaction with pollock, research is underway to study the dynamics and distribution of Steller prey and predators, and to evaluate the connection with commercial fishing (see NOAA's Marine Ecological Studies.) Check the NOAA/NMFS FY2000 Fisheries Management Plan and proposed catch limits. The University of British Columbia Fisheries Center has detailed fish catch statistics for this LME from 1950 to 1999. FAO has catch statistics for the last ten years. The data is provided in the chart "Eastern Bering Sea - LME 1."

Pollution and Ecosystem Health

(Source: Rear Admiral Harley D. Nygren, NOAA Corps)

(Source: Rear Admiral Harley D. Nygren, NOAA Corps) The statistics of many agencies tend to apply to all of Alaska, which makes a specific statistical breakdown for the East Bering Sea large marine ecosystem difficult to obtain. For information on [[coast]al] condition for Alaska, see EPA, 2001. For statistics concerning the Harbor seal, Beluga whale, and Harbor porpoise in the East Bering Sea LME, see Our Living Oceans, 1999, p. 231. Concerns for the health of this LME focus on petroleum amounts found in marine mammals, and the effects of the growing industrialization of the region. However, population levels of marine mammals in thecoastal areas of this LME are still low compared to other shallow seas. The Bering Sea has low levels of toxic contaminants, but these have been rising over the last 50 years due to increased human activities (mining, fishing, and oil exploration). This increase is linked to the long-range transport of contaminants through the ocean and atmosphere from other regions. Cold region [[ecosystem]s] such as the Bering Sea are more sensitive to the threat of contaminants than warmer regions because the loss and breakdown of these contaminants are delayed in colder areas. Also, animals high in the food web with relatively large amounts of fat tend to have high concentrations of organic contaminants such as pesticides, herbicides and PCBs. This causes concerns about human health in the region, particularly for Alaska natives (for instance, the Aleut community) who rely on marine mammals and seabirds as food sources.

Socio-economic Conditions

(Source: Rear Admiral Harley D. Nygren, NOAA Corps)

(Source: Rear Admiral Harley D. Nygren, NOAA Corps) 65,000 native Americans live on the shores of the East Bering Sea, and depend on its resources for their subsistence in food. Alaska natives benefit from individual fishing quotas or IFQs. There are also community development quotas. While the East Bering Sea is home to a valuable offshore fishing industry, the interests of US factory trawlers differ markedly from those of small fisheries (Fisheries and aquaculture). For an article on the political economy of the walleye pollock fishery, see Criddle and Mackinko, 2000. National Fisherman, September 2003, mentions a US country-of-origin labeling initiative that will remove loopholes that allow blending by countries playing the reprocessing and refreezing business. For a historical perspective on the importance of fisheries to the Bering Sea communities, read "Human Use-Fisheries" in The Bering Sea Ecosystem reference book.

Governance

The East Bering Sea large marine ecosystem is bordered by the USA (State of Alaska). The North Pacific Fishery Management Council manages fisheries with the goal of maintaining stable yields by shifting harvest allocations among species. The Bureau of Indian Affairs has responsibility to protect and improve trust assets of Alaska natives. In 2001, a Bering Sea Fisheries Conference took place which included Russian organizations, stakeholders, fishermen, salmon conservationists, and oil exploitation interests.

Articles and LME Volumes G. Carleton Ray and Bruce P. Hayden, 1993. Marine biogeographic provinces of the Bering, Chukchi and Beaufort seas. In: Large Marine Ecosystems: stress, mitigation and sustainability, edited by K. Sherman, LM Alexander and B.D. Gold, 1993. ISBN: 087168506X (East Bering Sea large marine ecosystem) . * EPA, 2001. National Coastal Condition Report. * FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO)), 2003. Trends in oceanic captures and clustering of large marine ecosystems: 2 studies based on the FAO capture database. FAO fisheries technical paper 435. 71 pages. * Incze, Lewis and J.D. Schumacher. 1986. "Variability of the Environment and Selected Fisheries Resources of the Eastern Bering Sea Ecosystem." In Kenneth Sherman and Lewis M. Alexander (eds.), Variability and Management of Large Marine Ecosystems (Boulder: Westview). AAAS Selected Symposium 99. ISBN: 0813371457. * Livingston, P.A., L-L. Low, and R.J. Marasco. 1999. "Eastern Bering Sea Ecosystem Trends." in Kenneth Sherman and Qisheng Tang (eds), Large Marine Ecosystems of the Pacific Rim: Assessment, Sustainability, and Management. (Blackwell Science) pp. 140-162. ISBN: 0632043369. * J.D Schumacher, N.A. Bond, R.D. Brodeur, P.A. Livington, J.M. Napp and P.J. Stabeno, 2003. Climate Change in the Southeastern Bering Sea and some consequences for its biota (volume in press).

Other References

- Bailey, K.M., and Dunn, J. 1979. Spring and summer foods of walleye pollock, Theragra chalcogramma, in the eastern Bering Sea. Fish. Bull. US. 77:304-308.

- Coachman, L.K., and Aagaard, K. 1981. Re-evaluation of water transports in the vicinity of Bering Strait. In The Eastern Bering Sea Shelf: Oceanography and resources, Volume 1, pp. 95-110. Ed. By D.W. Hood and J.A. Calder. Univ. Washington Press, Seattle, 1339 pp.

- Commission on Geosciences, Environment and Resources. 1996. The Bering Sea Ecosystem. ISBN: 0309075246.

- Criddle, K.R. and Mackinko, S., 2000. Political economy and profit maximization in the Eastern Bering Sea fishery for walleye pollock. IIFET 2000 Proceedings.

- Dragoo, D.E. and Dragoo, B.K. 1994. Results of Productivity Monitoring of Kittiwakes and Murres at St. George Island, Alaska in 1993. US Fish and Wildlife Service Report AMNWR 94/06. Homer, Alaska.

- Otto, R.S. 1993. Recent changes in the species composition of Bering Sea Fishery Resources. An oral presentation to the National Research Council. Kodiak, AK: National Marine Fisheries Service, Kodiak Laboratory.

- Our Living Oceans. Report on the Status of U.S. Living Marine Resources, 1999. NOAA. 301 pages

- Smith, G.B., and Allen, M.J., and Walters, G.E. 1984. Relationships between walleye pollock, other fish, and squid in the eastern Bering Sea. In Proc. Workshop of walleye pollock and its ecosystem in the eastern Bering Sea, pp. 161-191. Ed. By D.H. Ito. NOAA Tech. Memo. NMFS FNWC-62, 292pp.

- Straty, R.R. 1981. Trans-shelf movements of Pacific salmon. In The eastern Bering Sea Shelf: Oceanography and resources, pp. 575-595. Ed. By D.W.Hood and J.A. Calder. Univ. Washington Press, Seattle, 1339 p. ISBN: 0295958847.

- Takahashi, Y, and Yamaguchi, H. 1972. Stock of the Alaska pollock in the eastern Bering Sea. Bull. Jpn. Soc. Sci. Fish. 38:418-419.

- Wespestad, V. 1993. Walleye Pollock. In Stock Assessment and Fishery Evaluation Report for the Groundfish Resources of the Bering Sea/Aleutian Islands Regions as Projected for 1994. Anchorage, AK: North Pacific Fishery Management Council.

| Disclaimer: This article contains certain information that was originally published by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). Topic editors and authors for the Encyclopedia of Earth have edited its content and added new information. The use of information from the NOAA should not be construed as support for or endorsement by that organization for any new information added by EoE personnel, or for any editing of the original content. |