Dracunculiasis

Contents

- 1 Introduction

- 1.1 What is dracunculiasis?

- 1.2 How does Guinea worm disease spread?

- 1.3 What are the signs and symptoms of Guinea worm disease?

- 1.4 What is the treatment for Guinea worm disease?

- 1.5 Where is Guinea worm disease found?

- 1.6 Who is at risk for infection?

- 1.7 Is Guinea worm disease a serious illness?

- 1.8 Is a person immune to Guinea worm disease once he or she has it?

- 1.9 How can Guinea worm disease be prevented?

- 2 CDC Disclaimers

- 3 References

Introduction

Dracunculiasis (guinea worm disease) is caused by the nematode (roundworm) Dracunculus medinensis. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has provided the following answers to questions about the organism and the disease: (Dracunculiasis)

What is dracunculiasis?

Dracunculiasis, more commonly known as Guinea worm disease (GWD), is a preventable infection caused by the parasite Dracunculus medinensis. Infection affects poor communities in remote parts of Africa that do not have safe water to drink.

Currently, many organizations, including The Global 2000 program of The Carter Center of Emory University, UNICEF, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and the World Health Organization (WHO) are helping the last 5 countries in the world (Sudan, Ghana, Mali, Niger, and Nigeria) to eradicate the disease. Since 1986, when an estimated 3.5 million people were infected annually, the campaign has eliminated much of the disease]].

In 2007, only 9,585 cases of GWD were reported. Most of those cases were from Sudan (61%) and Ghana (35%). All affected countries are aiming to eliminate Guinea worm disease as soon as possible.

How does Guinea worm disease spread?

Approximately 1 year after a person drinks contaminated water, the adult female Guinea worm emerges from the skin of the infected person. Persons with worms protruding through the skin may enter sources of drinking water and unwittingly allow the worm to release larvae into the water. These larvae are ingested by microscopic copepods (tiny "water fleas") that live in these water sources. Persons become infected by drinking water containing the water fleas harboring the Guinea worm larvae.

Once ingested, the stomach acid digests the water fleas, but not the Guinea worm larvae. These larvae find their way to the small intestine, where they penetrate the wall of the intestine and pass into the body cavity. During the next 10-14 months, the female Guinea worm larvae grow into full size adults, 60-100 centimeters (2-3 feet) long and as wide as a cooked spaghetti noodle. These adult female worms then migrate and emerge from the skin anywhere on the body, but usually on the lower limbs.

A blister develops on the skin at the site where the worm will emerge. This blister causes a very painful burning sensation and it ruptures within 24-72 hours. Immersion of the affected limb into water helps relieve the pain but it also triggers the Guinea worm to release a milky white liquid containing millions of immature larvae into the water, thus contaminating the water supply and starting the cycle over again. For several days after it has emerged from the ulcer, the female Guinea worm is capable of releasing more larvae whenever it comes in contact with water.

What are the signs and symptoms of Guinea worm disease?

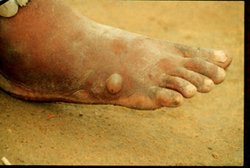

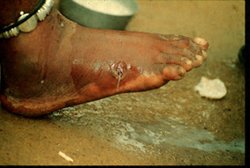

Infected persons do not usually have symptoms until about one year after they become infected. A few days to hours before the worm emerges, the person may develop a fever, swelling, and pain in the area. More than 90% of the worms appear on the legs and feet, but may occur anywhere on the body.

The female guinea worm induces a painful blister. (Source: CDC; Credit: The Carter Center) |

The worm emerges as a whitish filament in the center of a painful ulcer which is often secondarily infected. (Source: CDC; Credit: The Carter Center) |

People, in remote, rural communities who are most commonly affected by Guinea worm disease (GWD) frequently do not have access to medical care. Emergence of the adult female worm can be very painful, slow, and disabling. Frequently, the skin lesions caused by the worm develop secondary bacterial infections, which exacerbate the pain, and extend the period of incapacitation to weeks or months. Sometimes permanent disability results if joints are infected and become locked.

What is the treatment for Guinea worm disease?

There is no drug to treat Guinea worm disease (GWD) and no vaccine to prevent infection. Once the worm emerges from the wound, it can only be pulled out a few centimeters each day and wrapped around a piece of gauze or small stick. Sometimes the worm can be pulled out completely within a few days, but this process usually takes weeks or months. Analgesics, such as aspirin or ibuprofen, can help reduce swelling; antibiotic ointment can help prevent bacterial infections. The worm can also be surgically removed by a trained doctor in a medical facility before an ulcer forms.

Where is Guinea worm disease found?

Dracunculiasis now occurs only in 5 countries in sub-Saharan Africa. Transmission of the disease is most common in very remote rural villages and in areas visited by nomadic groups. In 2007, the two most endemic countries, Sudan and Ghana, reported 9,173; 5,815 and 3,358 cases of Guinea worm disease (GWD), respectively. Other endemic countries reporting cases of GWD in 2007 were: Mali (313 cases), Nigeria (73 cases), and Niger (14 cases).

Asia is now free of the disease. Transmission of GWD no longer occurs in several African countries, including Benin, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Cote d'Ivoire, Ethiopia, Kenya, Mauritania, Senegal, Togo, and Uganda. No locally acquired cases of disease have been reported in these countries in the last year or more. The treat of case importations from the remaining endemic countries requires that surveillance be maintained in formerly endemic areas until offical certification. The World Health Organization has certified 180 countries free of transmission of dracunculiasis, including six formerly endemic countries: Pakistan (in 1996), India (in 2000), Senegal and Yemen (in 2004), Central African Republic and Cameroon (in 2007).

Who is at risk for infection?

Anyone who drinks standing pond water contaminated by persons with GWD is at risk for infection. People who live in villages where the infection is common are at greatest risk.

Is Guinea worm disease a serious illness?

Yes. The disease causes preventable suffering for infected persons and is a heavy economic and social burden for affected communities. Emgerence of the adult female worms can be very painful, slow, and disabling. Parents who have active Guinea worm disease may not be able to care for their children. They are also prevented from working in their fields and tending their animals. Because worm emergence usually occurs during planting and harvesting season, heavy crop losses may result leading to financial problems for the entire family. Children may be required to work the fields or tend animals in place of their disabled parents, preventing them from attending school. Therefore, GWD is both a disease of poverty and also a cause of poverty because of the disability it causes.

Is a person immune to Guinea worm disease once he or she has it?

No. Infection does not produce immunity, and many people in affected villages suffer disease year after year.

How can Guinea worm disease be prevented?

Because GWD can only be transmitted via drinking contaminated water, educating people to follow these simple control measures can completely prevent illness and eliminate transmission of the disease:

- Drink only water from underground sources (such as from borehole or hand-dug wells) free from contamination.

- Prevent persons with an open Guinea worm ulcer from entering ponds and wells used for drinking water.

- Always filter drinking water, using a cloth filter, to remove the water fleas.

Additionally, unsafe sources of drinking water can be treated with an approved larvicide, such as ABATE®*, that kills copepods, and communities can be provided with new safe sources of drinking water, or have existing dysfunctional ones repaired.

CDC Disclaimers

- Use of trade names is for identification only and does not imply endorsement by the Public Health Service or by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

- This fact sheet is for information only and is not meant to be used for self-diagnosis or as a substitute for consultation with a health care provider. If you have any questions about the disease described above or think that you may have a parasitic infection, consult a health care provider.

References

| Disclaimer: This article is taken wholly from, or contains information that was originally published by, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Topic editors and authors for the Encyclopedia of Earth may have edited its content or added new information. The use of information from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) should not be construed as support for or endorsement by that organization for any new information added by EoE personnel, or for any editing of the original content. |