Coral diseases (About the EoE)

Contents

Coral diseases

Coral diseases and diseases to other reef organisms are having significant, negative impacts on the structure, functioning and appearance of coral reefs. The number, prevalence, and impacts of diseases of corals and many other types of marine animals have been increasing over the last 20 to 30 years. On some coral reefs, the effects of disease have been of a similar magnitude to more familiar disturbances, such as outbreaks of the Crown-of-thorns starfish in the Indo-Pacific and worldwide coral bleaching associated with elevated sea temperatures.

A new scientific awareness of diseases on coral reefs leads to a host of questions about the novelty of recently discovered syndromes, the importance of observed trends toward increasing infection rates, and the extent to which human activities are responsible. This statement, issued by the International Society for Reef Studies (ISRS), summarizes current knowledge on the subject. It was compiled by an ad hoc group of scientists in ISRS, composed of individuals who are directly or indirectly considering disease as part of their research programs.

Coral disease ecology

Disease is a natural process that has been poorly studied in the oceans because of its ephemeral nature. Epidemics in animal populations, called epizootics, are a serious threat to the health of coral reefs worldwide. Recent observations of epizootics affecting sea urchins and corals show that diseases on reefs can devastate host populations and act as agents of rapid and dramatic community change. Marine pathologists and microbiologists are attempting to identify the causes of infection, but the pathogens responsible for most diseases affecting reef organisms remain elusive. These difficulties complicate efforts by scientists and managers to study outbreaks and to determine if control measures are warranted. It is becoming clear, however, that human activity is at least partially responsible for disease outbreaks on coral reefs over the past decade. For example, both nutrient pollution and elevated ocean temperature have been linked with coral epizootics.

Basic Coral Biology

Corals are colonial animals related to sea anemones. They lay down the limestone foundations of coral reefs. Coral reefs are important because they protect tropical shorelines from damaging storm waves, and because they provide habitat for many of the fish and invertebrate species that feed a substantial proportion of the world's population. Like all living organisms, corals are prone to diseases of various sorts. A few long-term ecological studies of coral reefs suggest that the incidence of disease has risen over the past several decades. In most cases, however, historical information does not exist, and it is difficult to determine whether the increase in disease is real or simply a reflection of increased research activity. Recent scientific reviews list four to six confirmed coral diseases in the Caribbean region alone; other estimates, based only on observed symptoms, run as high as fifteen. Bacteria, fungi, and cyanobacteria ("blue-green algae") are known to cause diseases in corals. Sick and dying corals are cause for concern, because coral death slows the rate of reef construction. Reefs devastated by disease (or by other causes of coral mortality) may not be able to keep up with sea-level rise, which is naturally slow but may be accelerating due to global warming. As reef growth slows, the processes that degrade reefs assume greater importance, and fish and other seafood resources decline as well.

Caribbean Coral Diseases

Three coral diseases—"white-band," "black-band," and "plague"—were first reported in the Caribbean in the 1970s. The first documented, regional-scale epizootic, however, affected the long-spined sea urchin, Diadema antillarum. In 1983-84, a disease carried by ocean currents, and possibly in the ballast water of ships, killed more than 95 percent of the Diadema throughout the Caribbean. This epizootic clearly demonstrated that diseases can have major impacts on reef ecology. Before its mass mortality, Diadema was an important herbivore. It ate fast-growing fleshy algae (seaweeds), keeping space free for corals to survive and grow. After the urchins died, algae increased dramatically on many Caribbean reefs. They colonized corals that had been killed by hurricanes and by diseases, particularly white-band disease. Since then algal growth has been so rapid on some reefs that the surviving corals have been unable to continue growing, and small, newly-settled corals are simply being overgrown and killed.

The infective agent of white-band disease type II appears to be Vibrio charchariae. White-band disease infected populations of staghorn and elkhorn coral (Acropora cervicornis and Acropora palmata) throughout the Caribbean region in the 1980s and 1990s, inflicting enormous losses. This epizootic was the principle cause of the drastic loss of coral cover in the Caribbean during this period. Because Diadema also disappeared nearly simultaneously, algae rapidly colonized the dead coral skeletons. Paleontologists working on fossil reefs in Belize recently uncovered evidence that the epizootic of white-band disease is without historical precedent: a regional dieoff of staghorn coral has not occurred previously in at least the past several thousand years. Staghorn and elkhorn corals are major constructors of reef framework. Their loss has dramatically altered the ecology of Caribbean reefs and may slow future rates of reef growth. Both species are were listed as vulnerable in 2006 under the US Endangered Species Act.

Many marine scientists suspect that human activities, such as pollution and changing patterns of land use, promoted the spread of white-band disease in Florida and the Caribbean. There is little evidence for a human connection, however, other than the historical novelty of the outbreak. Eutrophication, or nutrient pollution, may be an important source of stress to reef organisms. This stress may compromise disease resistance, allowing infections to take hold and new diseases to emerge. A fungal disease of sea fans appears to provide a link to human activity. The fungus, Aspergillus sydowii, has infected large populations of sea fans in the Florida Keys and throughout the Caribbean. Aspergillus sydowii is thought to be a land-based fungus that has invaded the marine environment via the sediment in terrestrial runoff.

Reliable information exists for two other diseases: black-band disease and "plague type II." Black-band disease, caused by a consortium of bacteria (including cyanobacteria) attacks and kills massive, head-forming corals. Black-band disease could pose a serious threat to populations of brain and star corals, which, like the Acropora species, are important components of reef framework in the Caribbean. Like black-band disease, plague type II attacks and kills head corals. Plague type II was first reported in Florida in 1995, but it has now been observed elsewhere in the Caribbean. In this case, rigorous microbiological work showed that the disease is caused by a single bacterium, a new species of Sphingomonas.

Other Coral Diseases

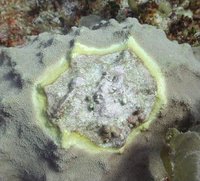

A coral colony with white syndrome. (Photo credit: AIMS LTMP)

A coral colony with white syndrome. (Photo credit: AIMS LTMP) Epizootics are killing corals and many other important species on reefs of the Pacific, Indian, and Atlantic Oceans. Black-band disease and white-band disease have now been identified on reefs throughout the tropical Indo-Pacific, including the Red Sea, Mauritius, the Philippines, Papua New Guinea, and the Great Barrier Reef of Australia. In the Arabian Gulf, the newly discovered yellow-band disease is affecting up to 75 percent of the coral colonies in local populations. In addition, diseases of algae, sponges, and fish have been and continue to be identified.

One disease of particular concern in the Pacific is white syndrome. White syndrome is an emerging disease of Pacific reef-building corals, reported in 17 species from families including Acroporidae, Pocilloporidae, and Faviidae, which comprise the majority of dominant species on the GBR. Little is known about the etiology of white syndrome, although it is presumably infectious and the characteristics are similar to Caribbean white diseases such as white band and white plague. Like the Caribbean white diseases, white syndrome could comprise a group of distinct diseases with similar signs. White syndrome can cause either partial or whole colony mortality and is characterized by a white band of tissue or recently exposed skeleton that moves across the colony as the disease progresses. Recent research indicates that major outbreaks of white syndrome only occur on reefs with high coral cover after especially warm years. The disease is usually absent on cooler, low-cover reefs.

Reefs throughout the world were stressed by unusually high sea temperatures in 1997-98, and the worldwide episode of coral bleaching that resulted may render corals more susceptible to disease. In general, the severity of marine diseases could increase with temperature for several reasons. For example, some pathogens prefer the warmer temperatures, enabling them to reproduce more quickly and in some cases causing them to become more virulent. Additionally, many host animals such as corals and tropical fish can become stressed by abnormally high temperatures. This can wreak havoc with their immune system, making them more susceptible to opportunistic parasites and pathogens. In the Mediterranean Sea the bacterium Vibrio shiloi is the causative agent of bleaching in the coral species Oculina patagonica. Disease outbreaks have been linked to predation by coral-eating snails in the Red Sea. In general, however, the connections among bleaching, predation, and disease remain obscure.

The role of disease on coral reefs and possible interactions with environmental influences should be a research priority over the next several years. Despite the frustrating inability to identify pathogens in most cases, reef scientists have detected symptoms that could represent over a dozen new diseases. Diseases are now recorded as part of standard reef-monitoring programs throughout the world, including the Caribbean Coastal Marine Productivity (CARICOMP) Program, the worldwide Reef Check, the Atlantic and Gulf Reef Assessment (AGRA) Program, and a variety of government and private programs in Australia.

Because corals grow slowly, live for decades to centuries, and reproduce sporadically, today's diseases will probably have consequences that reach far into the future. Multidisciplinary efforts combining microbiology, coral physiology and pathology, ecological monitoring, and paleontology will be necessary to understand the causes and consequences of these diseases and to devise management strategies in response.

Further reading

- NOAA CORIS coral disease web site

- The International Society for Reef Studies web site

- Bruno, J. F., E. R. Selig, K. S. Casey, C. A. Page, B. L. Willis, C. D. Harvell, H. Sweatman, and A. M. Melendy. 2007. Thermal stress and coral cover as drivers of coral disease outbreaks. PLoS Biology 5:e124.

- Gil-Agudelo, D. L., G. W. Smith, and E. Weil. 2006. The white band disease type II pathogen in Puerto Rico. International Journal of Tropical Biology and Conservation 54:59-67.

- Precht, W. F., A. W. Bruckner, R. B. Aronson, and R. J. Bruckner. 2002. Endangered acroporid corals of the Caribbean. Coral Reefs 21:41-42.

- Weil, E., G. W. Smith, and D. L. Gil-Agudelo. 2006. Status and progress in coral reef disease research. Diseases of Aquatic Organisms 69:1-7.

- Willis, B. L., C. A. Page, and E. A. Dinsdale. 2004. Coral disease on the Great Barrier Reef. Pages 69-104 in E. Rosenberg and Y. Loya, editors. Coral Health and Disease. Springer-Verlag, Berlin.

| Disclaimer: This article contains information that was originally published by the International Society for Reef Studies. Topic editors and authors for the Encyclopedia of Earth have edited its content and added new information. The use of information from the International Society for Reef Studies should not be construed as support for or endorsement by that organization for any new information added by EoE personnel, or for any editing of the original content. |