Challenge of the arid west

| Topics: |

Lead Author: Donald Worster (other articles)

Content Partners: National Humanities Center (other articles) and TeacherServe (other articles)

Article Topics: Environmental history

This article has been reviewed and approved by the following Topic Editor: Brian Black (other articles)

EDITOR'S NOTE: This entry was originally published as "The Challenge of the Arid West" in the series "Nature Transformed: The Environment in American History," developed by the National Humanities Center and TeacherServe. Citations should be based on the original essay.

Introduction

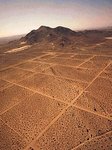

Flying west across the continent, the traveler notices a dramatic change in the American landscape—from wet to dry, from green forests and cornfields to sagebrush plains and harsh deserts with only scattered stands of trees at the higher elevations. For more than a century now we have called that dry half of the continent the West. It starts on the Great Plains and stretches over a thousand dusty miles to sun-baked Los Angeles and an anomalous fringe of temperate rain forest in the Pacific Northwest.

Today, millions of people live here, but they tend to concentrate in a few places—oases where water is delivered—rather than spreading out on the ground. In fact, much of this region is still unsettled (with fewer than two people per square mile) and likely will never become settled. That fact is not due to any of the historical forces we commonly talk about—Puritanism, the Enlightenment, capitalism, slavery, or television—although they all have had their influence on this region. No, the relative emptiness of much of the West is due to the persisting power of nature to set terms to human life.

Each set of people who have come into this country has had to deal with those environmental realities. Only the Spanish-speaking immigrants from the Iberian Peninsula, which is similarly arid, came with much experience; other immigrants from ancient or modern Asia, Africa, or northern Europe have had a lot more to learn. Growing numbers of Americans began to encounter the arid West in the 1820s, journeying along the Santa Fe Trail, and in the 1840s, when the Mormons arrived in Utah while hundreds of thousands of other citizens plodded farther overland to find California gold. They debated the West's promise: would it set a rigid limit on the country's growth, a "Great American Desert" that had little to offer, or would it be redeemable by agriculture and other forms of labor?

In 1878 John Wesley Powell, who led the first exploration of the upper Colorado River and the Grand Canyon, published a government report on "the arid region," which he defined as the territory west of the hundredth meridian. That line approximates the point where rainfall drops to less than twenty inches per year on average, which was not enough to sustain the leading domesticated crops. Powell recommended sweeping changes in the public land laws to allow small, irrigated farms and livestock ranches, but also to encourage a less individualistic way of living on the land. Americans must learn to work together, he argued, if they wanted to see the West support secure, prosperous homes, and always they must worry about the threat of monopoly over the vital natural resource of water.

The twentieth century has launched massive projects to control and manage the scarce water supply, most dramatically with the dedication of Hoover Dam in 1935. Thousands of large and small dams, canals, reservoirs, and aqueducts eventually captured the water from far-apart rivers and transported it to agriculturists and to city consumers. Still, the West remains predominately brown, barren, and starkly defiant. Americans may have constructed a "hydraulic civilization" here, a society dependent on large-scale hydraulic engineering for survival, but they have not really turned scarcity into unlimited abundance. The battle to control water, which has been at the heart of the West's history, goes on, and none of the engineering marvels is secure or permanent. The fact that huge numbers of people now live here, that aridity did not stop the westward movement dead in its tracks, does not mean that, in the end, nature had no power or influence over American history, or is no longer a threat to the future.

Historical Work

The first historian to address the challenge of aridity was Walter Prescott Webb in his book The Great Plains (1931), which argued that the natural environment created "an institutional fault-line" across the nation. Laws and technologies developed in humid America could not get over that line, forcing people to make such innovations as barbed wire (to substitute for wooden fences) and windmills (to pump underground water). Webb saw a nation divided by nature and unequal in development. Moreover, he raised a broader question that previous historians had ignored: what is the role of nature in social evolution? That question took on new significance in the Dust Bowl years. Wind erosion and forced migration caused many to question whether westerners themselves had understood their environmental challenges sufficiently and had learned to adapt to drought cycles and aridity. Where Webb had seen a distinctly new region emerging, others saw a failed civilization that had been foretold by Powell.

In the early postwar period, Powell's star continued to ascend until he became a shining hero to many scholars and conservationists. They were less interested in the role of nature in history and more in the cultural blinders that Americans wore when they moved west. Two classic works that followed Powell in criticizing maladaptive attitudes were Henry Nash Smith's Virgin Land (1950) and Wallace Stegner's biography of Powell, Beyond the Hundredth Meridian (1954). Both of them found the nation and the region alike to be unrealistic in expectations. Smith showed how an "agrarian myth," joined with imperial ambitions, convinced people that they could create a "garden of the world" where deserts had ruled. Stegner, one of the most influential western voices in the twentieth century, described a battle between, on the one hand, Powell the scientist and, on the other hand, regional political and economic leaders who pursued extravagant dreams of growth.

Following the rise of the environmental movement and the new field of environmental history, scholars have focused more and more on western water politics. Although some still celebrate achievements of the Bureau of Reclamation and other dam-building agencies, most historians have become more critical of how water has been managed in the West. Norris Hundley, author of three books on the subject—The Great Thirst (1992), Water and the West (1975), and Dividing the Waters (1966)—has argued that the government overestimated the amount of water available for use, particularly in the Colorado River, creating serious legal conflicts among the states and between the United States and Mexico. He sees a history of chaos and disorder in water planning—inefficiency, waste, and strife—instead of coordinated development or cooperative spirit.

That view has been echoed in the writings of Robert Kelley in Battling the Inland Sea (1989) and Donald Pisani in, among others, Water, Land, and Law in the West (1996) who, like Hundley, have emphasized California. In their opinion, the federal government has not done nearly enough to govern water; it has built massive dams and other infrastructure but has not used its power to settle questions of distribution, leaving them instead to a cacophony of local interests.

To a point they are right; Washington has seemed reluctant to confront the self-seeking demands of land and water entrepreneurs who would impose their values on nature and society in the West. But, as I have argued in a number of works, the federal government has more often shared rather than opposed those values. Working together rather than in opposition, capital and bureaucracy have drastically reordered the arid region. They have shared a common logic, a broad plan of conquest, in the name of economic growth. They have achieved, as intended, an "empire" that today boasts forty million irrigated acres and sprawling metropolises. They have accumulated power as well, just as Powell feared they would. The most intriguing question for this historian is how long they will be able to hold on to that power or maintain their imposed order over a desert that can never really be conquered or evaded.

Whether culture or nature, society or aridity, proves dominant in the long term is an issue that can only be settled by scholars in the future. Most likely, neither force will win out absolutely and civilization will continue to face the challenge of how to live successfully in this difficult land.

Further Reading

- Diamond, Jared M., 1997. Guns, Germs, and Steel: The Fate of Human Societies. Norton, New York. ISBN: 0393061310

- Hundley, Norris, Jr., 1992. The Great Thirst: Californians and Water, 1770s-1990s. University of California Press, Berkeley. ISBN: 0520077865

- Hundley, Norris, Jr., 1975. Water and the West: The Colorado River Compact and the Politics of Water in the American West. University of California Press, Berkeley. ISBN: 0520027000

- Hundley, Norris, Jr., 1966. Dividing the Waters: A Century of Controversy between the United States and Mexico. University of California Press, Berkeley.

- Kelley, Robert Lloyd, 1989. Battling the Inland Sea: American Political Culture, Public Policy, and the Sacramento Valley, 1850-1986. University of California Press, Berkeley. ISBN: 0520064879

- Pisani, Donald J., 1996. Water, Land, and Law in the West: The Limits of Public Policy, 1850-1920. University Press of Kansas, Lawrence. ISBN: 0700611118

- Smith, Henry Nash, 1950. Virgin Land: The American West as Symbol and Myth. Harvard University Press, Cambridge. ISBN: 0674939557

- Stegner, Wallace Earle, 1954. Beyond the Hundredth Meridian: John Wesley Powell and the Second Opening of the West. Houghton, Mifflin, Boston. ISBN: 0140159940

- Webb, Walter Prescott, 1931. The Great Plains. Ginn, Boston. ISBN: 0803297025

- Worster, Donald, 1979. Dust Bowl: The Southern Plains in the 1930s. Oxford University Press, New York. ISBN: 0195174895

- Worster, Donald, 2000. A River Running West: The Life of John Wesley Powell. Oxford University Press, New York, Oxford. ISBN: 0195156358

- Worster, Donald, 1985. Rivers of Empire: Water, Aridity, and the Growth of the American West. Pantheon, New York. ISBN: 039451680X

- Worster, Donald, 1992. Under Western Skies: Nature and History in the American West. Oxford University Press, New York, Oxford. ISBN: 0195086716

- Worster, Donald, 1994. An Unsettled Country: Changing Landscapes of the American West. University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque. ISBN: 0826314813