Biological diversity in the Philippines

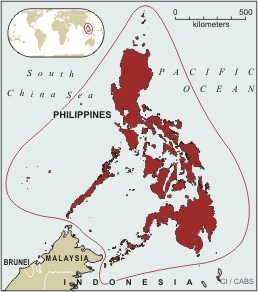

The world's second largest archipelago country after Indonesia, the Philippines includes more than 7,100 islands covering 297,179 km2 in the westernmost Pacific Ocean. The Philippines lies north of Indonesia and directly east of Vietnam. The country is one of the few nations that is, in its entirety, both a hotspot and a megadiversity country, placing it among the top priority hotspots forglobal conservation.

The archipelago is formed from a series of isolated fragments that have long and complex geological histories, some dating back 30-50 million years. With at least 17 active volcanoes, these islands are part of the "Ring of Fire" of the Pacific Basin. The archipelago stretches over 1,810 kilometers from north to south. Northern Luzon is only 240 kilometers from Taiwan (with which it shares some floristic affinities), and the islands off southwestern Palawan are only 40 kilometers from Malaysian Borneo. The island of Palawan, which is separated from Borneo by a channel some 145 meters deep, has floristic affinities with both the Philippines and Borneo in the Sundaland Hotspot, and strong faunal affinities with the Sunda Shelf.

Hundreds of years ago, most of the Philippine islands were covered in rain forest. The bulk of the country was blanketed by lowland rainforests dominated by towering dipterocarps (Dipterocarpaceae), prized for their beautiful and straight hardwood. At higher elevations, the lowland forests are replaced by montane and mossy forests that consist mostly of smaller trees and vegetation. Small regions of seasonal forest, mixed forest and savanna, and pine-dominated cloud forest covered the remaining land area.

Coron Island, Palawan. (Source: © Conservation International, photo by Haroldo Castro)

Coron Island, Palawan. (Source: © Conservation International, photo by Haroldo Castro) Contents

Unique and Threatened Biodiversity

The patchwork of isolated islands, the tropical location of the country, and the once extensive areas of rainforest have resulted in high species diversity in some groups of organisms and a very high level of endemism. There are five major and at least five minor centers of endemism, ranging in size from Luzon, the largest island (103,000 km2), which, for example, has at least 31 endemic species of mammals, to tiny Camiguin Island (265 km2) speck of land north of Mindanao, which has at least two species of endemic mammals. The Philippines has among the highest rates of discovery in the world with sixteen new species of mammals discovered in the last ten years. Because of this, the rate of endemism for the Philippines has risen and likely will continue to rise.

Plants

At the very least, one-third of the more than 9,250 vascular plant species native to the Philippines are endemic. Plant endemism in the hotspot is mostly concentrated at the species level; there are no endemic plant families and 26 endemic genera. Gingers, begonias, gesneriads, orchids, pandans, palms, and dipterocarps are particularly high in endemic species. For example, there are more than 150 species of palms in the hotspot, and around two-thirds of these are found nowhere else in the world. Of the 1,000 species of orchids found in the Philippines, 70 percent are restricted to the hotspot.

The broad lowland and hill rain forests of the Philippines, which are mostly gone today, were dominated by at least 45 species of dipterocarps. These massive trees were the primary canopy trees from sea level to 1,000 meters. Other important tree species here include giant figs (Ficus spp.), which provide food for fruit bats, parrots, and monkeys, and Pterocarpus indicus, like the dipterocarps, is valued for its timber.

Vertebrates

Birds

The red-bellied pitta (Pitta erythrogaster), a forest bird that feeds on invertebrates, was once considered rare but is now known to be widespread and moderately common. Two other species of pitta -- the azure-breasted pitta (Pitta steerii, VU) and the wiskered pitta (Pitta kochi) -- are endemic to the Philippines and threatened. (Source: © D. Willard)

The red-bellied pitta (Pitta erythrogaster), a forest bird that feeds on invertebrates, was once considered rare but is now known to be widespread and moderately common. Two other species of pitta -- the azure-breasted pitta (Pitta steerii, VU) and the wiskered pitta (Pitta kochi) -- are endemic to the Philippines and threatened. (Source: © D. Willard) There are over 530 bird species found in the Philippines hotspot; about 185 of these are endemic (35 percent) and over 60 are threatened. BirdLife International has identified seven Endemic Bird Areas (EBAs in this hotspot: Mindoro, Luzon, Negros and Panay, Cebu, Mindanao and the Eastern Visayas, the Sulu archipelago, and Palawan. Like other taxa, birds exhibit a strong pattern of regional endemism. Each EBA supports a selection of birds not found elsewhere in the hotspot. The hotspot also has a single endemic bird family, the Rhabdornithidae, represented by the Philippine creepers (Rhabdornis spp.). In May 2004, a possibly new species of rail Gallirallus was observed on Calayan island in the Babuyan islands, northern Philippines. It is apparently most closely related to the Okinawa rail (Gallirallus okinawae) from the Ryukyu islands, Japan.

Perhaps the best-known bird species in the Philippines is the Philippine eagle (Pithecophaga jefferyi, CR), the second-largest eagle in the world. The Philippine eagle breeds only in primary lowland rain forest. Habitat destruction has extirpated the eagle everywhere except on the islands of Luzon, Mindanao and Samar, where the only large tracts of lowland rain forest remain. Today, the total population is estimated at less than 700 individuals. Captive breeding programs have been largely unsuccessful; habitat protection is the eagle's only hope for survival.

Among the hotspot’s other threatened endemic species are the Negros bleeding heart (Gallicolumba keayi, CR), Visayan wrinkled hornbill (Aceros waldeni, CR), Scarlet-collared flowerpecker (Dicaeum retrocinctum, VU), Cebu flowerpecker (Dicaeum quadricolor, CR), and Philippine cockatoo (Cacatua haematuropygia, CR).

Mammals

At least 165 mammal species are found in the Philippine hotspot, and over 100 of these are endemic (61 percent), one of the highest levels of mammal endemism in any hotspot. Endemism is high at the generic level as well, with 23 of 83 genera endemic to the hotspot. Rodent diversification in the Philippines is comparable with the radiation of honeycreepers in the Hawaiian Islands and finches in the Galapagos.

The largest and most impressive of the mammals in the Philippines is the tamaraw (Bubalus mindorensis, CR), a dwarf water buffalo that lives only on Mindoro Island. A century ago the population numbered 10,000 individuals; today only a few hundred animals exist in the wild. Other mammals endemic to the Philippines include: the Visayan and Philippine warty pigs (Sus cebifrons, CR and S. philippensis, VU); the Calamianes hog-deer (Axis calamaniensis, EN) and the Visayan spotted deer (Rusa alfredi, EN), which has been reduced to a population of a few hundred on the islands of Negros, Masbate and Panay; and the golden-capped fruit bat (Acerodon jubatus, EN), which, as the world's largest bat, has a wingspan up to 1.7 meters.

The Negros naked-backed fruit bat (Dobsonia chapmani), which was thought to be extinct in the Philippines, has recently been rediscovered, on the islands of Cebu in 2000 and Negros in 2003.

Reptiles

Reptiles are represented by about 235 species, some 160 of which are endemic (68 percent). Six genera are endemic, including the snake genus Myersophis, which is represented by a single species, Myersophis alpestris, on Luzon. The Philippine flying lizards from the genus Draco are well represented here, with about 10 species. These lizards have a flap of skin on either side of their body, which they use to glide from trees to the ground.

An endemic freshwater crocodile (Crocodylus mindorensis, CR) is considered the most threatened crocodilian in the world. In 1982, wild populations totaled only 500-1000 individuals; by 1995 a mere 100 crocodiles remained in natural habitats. The recent discovery of a population of this species in the Sierra Madre of Luzon brings new hope for its conservation, as does the implementation of projects aimed at raising awareness and protecting the crocodile’s habitat. The Crocodile Rehabilitation, Observance and Conservation (CROC) Project of the Mabuwaya Foundation is active in carrying out such projects.

Other unique and threatened reptiles include Gray's monitor (Varanus olivaceus, VU) and the Philippine pond turtle (Heosemys leytensis, CR). A newly discovered monitor lizard, Varanus mabitang, from Panay is only the second monitor species known in the world to specialize on a fruit diet.

Amphibians

There are nearly 90 amphibian species in the hotspot, almost 85 percent of which are endemic; these totals continue to increase, with the continuing discovery and description of new species. One interesting amphibian, the panther flying frog (Rhacophorus pardalis), has special adaptations for gliding, including extra flaps of skin and webbing between fingers and toes to generate lift during glides. The frog glides down from trees to breed in plants suspended above stagnant bodies of water. The frog genus Platymantis is particularly well represented with some 26 species, all of which are endemic; of these, 22 are considered threatened. The young of all Platymantis species undergo direct development, bypassing the tadpole stage. The hotspot is also home to the Philippine flat-headed frog (Barbourula busuangensis, VU), one of the world's most primitive frog species.

Freshwater Fishes

The Philippines has more than 280 inland fish, including nine endemic genera and more than 65 endemic species, many of which are confined to single lakes. An example is Sardinella tawilis, a freshwater sardine found only in Taal Lake. Sadly, Lake Lanao, in Mindanao, seems likely to have become the site of one of the hotspot’s worst extinction catastrophes, with nearly all of the lake’s endemic fish species now almost certainly extinct, primarily due to the introduction of exotic species (like Tilapia).

Invertebrates

About 70 percent of the Philippines’ nearly 21,000 recorded insect species are found only in this hotspot. About one-third of the 915 butterflies found here are endemic to the Philippines, and over 110 of the more than 130 species of tiger beetle are found nowhere else.

Human Impacts

Philippine coral reefs support among the highest levels of marine biodiversity in the world. They have been dramatically impacted by destructive fishing, which involves using dynamite and cyanide to catch fish, and sedimentation from poor land management practices. (Source: © Conservation International, photo by Tim Werner)

Philippine coral reefs support among the highest levels of marine biodiversity in the world. They have been dramatically impacted by destructive fishing, which involves using dynamite and cyanide to catch fish, and sedimentation from poor land management practices. (Source: © Conservation International, photo by Tim Werner) Along with its remarkable levels of species endemism, the Philippines is one of the world's most threatened hotspots, with only about seven percent of its original, old-growth, closed-canopy forest left. A mere three percent is estimated to remain in the lowland regions. About 14 percent of the original vegetation remains as secondary growth in various stages of degradation; these areas would probably be capable of regeneration if they are not disturbed further.

The Philippines has a population of 80 million people with livelihoods highly dependent on natural resources. Severe rural poverty and a high population growth rate (2.2 percent) and density (273 people per km2) have put enormous pressure on the remaining forests. Widespread use of timber became common 500 years ago, when the Spanish began using trees for the construction of their fleet. As late as 1945, two-thirds of the country was still covered by old-growth forest. However, in the following decades, logging rates accelerated rapidly. Between 1969 and 1988, 2,000 km2 were logged annually, three times the global rate for tropical forest conversion. Although there has been a decline in logging activities due to the state of its forests and the increasing awareness among the communities, illegal logging activities still persist in the countries remaining forests as witnessed in the December 2004 landslides.

Other imminent threats to Philippine forests include mining and land conversion. In 1997, regions where mining activities took place covered one-quarter of the country and included more than half of the remaining primary forest. The country's development objectives, which include road network development, irrigation, power and energy projects, and planned ports and harbors, still need to be harmonized with biodiversity conservation goals.

Introductions of exotic species (Biological diversity in the Philippines) have also taken a toll, particularly in wetlands. The following groups have had a particularly negative impact on wetland biodiversity: fish such as the giant catfish and black bass; toads and frogs, including the marine toad (Bufo marinus), the American bullfrog (Rana catesbeiana) and leopard frog (Rana tigrina); and aquatic plants like the water hyacinth and water fern.

Conservation Action and Protected Areas

This flying frog (Rhacophorus pardalis) in Aurora National Park, Luzon has special adaptations for gliding, including extra flaps of skin and webbing between fingers and toes to generate lift during glides. The frog glides down from trees to breed in plants suspended above stagnant bodies of water. (Source: © Rafe Brown)

This flying frog (Rhacophorus pardalis) in Aurora National Park, Luzon has special adaptations for gliding, including extra flaps of skin and webbing between fingers and toes to generate lift during glides. The frog glides down from trees to breed in plants suspended above stagnant bodies of water. (Source: © Rafe Brown) Conservationists fear that, without immediate intervention, the Philippines hotspot is on the brink of an extinction crisis. Logging concessions have not been eliminated from lowland forests, which have already been reduced to a tiny fraction of their original cover, and illegal logging is widespread.

National parks and protected areas are crucial for the conservation of Philippine biodiversity. However, only 11 percent of the total land area of the Philippines (approximately 32,000 km2) is protected. This figure drops to only six percent of the hotspot (18,000 km2) when only protected areas in IUCN categories I to IV are included. National park boundaries have not been well demarcated, there is little enforcement, and there is even debate over how many parks exist in the country. Two-thirds of parks have human settlements, and one-quarter of their lands have already been disturbed or converted to agriculture. On a positive note, at least five new protected areas were proclaimed in 2002. In October 2003, the Peablanca Protected Landscape and Seascape was greatly expanded, from 4,136 hectares to 118,108 hectares. More recently, the Quirino Protected Landscape, which covers 206,875 hectares in northeastern Luzon, was established through a presidential proclamation.

One way of ensuring that the network of protected areas adequately conserves biodiversity is through the conservation of Key Biodiversity Areas (KBAs), sites holding populations of globally threatened or geographically restricted species. KBAs are discrete biological units that contain species of global conservation concern and that can be potentially managed for conservation as a single unit. In the Philippines hotspot, Conservation International-Philippines in collaboration with the Field Museum in Chicago, Haribon Foundation and other local partners are in the process of identifying and delineating KBAs throughout the Philippines. This work, supported by CEPF, is a refinement of the broad-scale priorities identified during the 2000 Philippines Biodiversity Conservation Priority-Setting Process. It builds directly from the 117 Important Bird Areas defined by the Haribon Foundation, published in 2001. As IBAs are sites containing globally threatened, restricted-range, and congregatory species, they provide the starting point for the incorporation of data on other taxonomic groups to identify KBAs.

In addition to creating effective protected areas, basic field research is desperately needed to support conservation activities. New endemic species are being discovered all of the time, and this information feeds directly into the refinement and prioritization of KBAs. A range of other conservation activities are underway throughout the islands. For example, the Philippine Cockatoo Conservation Program on Palawan has made great progress in reducing the theft of this species' eggs. On Cebu, the recent rediscovery of several of the islands' presumed-extinct species (most famously the Cebu flowerpecker), has focused community conservation activities by the Cebu Biodiversity Conservation Foundation on protecting the island's last few hectares of forest. The Haribon Foundation and Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund have organized a Threatened Species Program to support such initiatives through the provision of small grants.

In the long term, it is clear that landscape- and seascape-scale conservation will be necessary to allow the Philippines' extraordinary biodiversity to persist. To this end, Conservation International and the Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund have been supporting conservation in biodiversity conservation corridors in the Sierra Madre, Palawan, and Eastern Mindanao regions. This work has included the establishment of the Philippine Eagle Alliance, to coordinate the work of the various conservation groups working within the range of this magnificent but seriously threatened flagship species for Philippine conservation.

Further Reading

| Disclaimer: This article is taken wholly from, or contains information that was originally published by, the Conservation International. Topic editors and authors for the Encyclopedia of Earth may have edited its content or added new information. The use of information from the Conservation International should not be construed as support for or endorsement by that organization for any new information added by EoE personnel, or for any editing of the original content. |