Africa's renaissance for the environment: freshwater

Contents

Issues

"Most countries require a big push in public investments to overcome the region’s high transport costs, generally small markets, lowproductivity agriculture, adverse agroclimatic conditions, high disease burden and slow diffusion of technology from abroad". (UN Millennium Project 2005a)

Access to safe drinking water and sanitation is critical to maintaining and improving health. In general, poor water supply and sanitation is a major public health problem throughout Africa. More than 50 percent of people in Africa suffer from water-related diseases such as cholera and infant diarrhoea. Improvements in safe water supply, and in particular in hygiene and sanitation, can reduce the incidence of cholera, diarrhoea as well as the number of deaths of children under five. Poor access to safe water and sanitation has been described as “the silent humanitarian crisis that each day takes thousands of lives” (UN Millennium Project 2005b). Conventional wisdom suggests that no single type of intervention has had greater overall impact upon economic development and public health than the provision of safe drinking water and proper sanitation. “Expanding water and sanitation coverage is not rocket science. It requires neither colossal sums of money nor breakthrough scientific discoveries and dramatic technological advances” (UN Millennium Project 2005b).

Freshwater resources (Opportunities from freshwater in Africa) have been described as life itself because they drive human life and activities, including agriculture, manufacturing, tourism, fisheries, and forestry, and they sustain the environment and biodiversity. Access to water has also been recognized as a fundamental human right. Water availability and access impacts on all three components of sustainable development: environment, society and economy. For example, about 180 million people in Africa – pastoralists, farmers and other land users – live on fragile drylands where growing numbers compete for water and land. More than 20 percent of the regional population’s protein comes from freshwater fisheries.

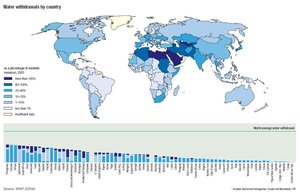

Despite their centrality to human and environmental vulnerability, and their potential to enhance the resilience of both, freshwater resources (Freshwater resources in Africa) are not evenly distributed across the region. Some sub-regions and countries, for example Central Africa and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, have more resources. Others, such as North Africa and Egypt, have less. Some of the sub-regions receive more than adequate rains, leading to devastating floods, while others are prone to severe droughts, impacting food production and exacerbating poverty and hunger.

In addition to issues related to access, availability and distribution, increasing pollution is presenting a serious challenge. Freshwater resources are also increasingly being polluted through human activity such as agriculture and mining. This compounds human health and well-being issues. At the beginning of 2005, a total of 280 million people in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) had no access to safe water and 454 million had no access to improved sanitation. Projections show that if current trends continue, by 2025 about 67 percent of the world’s population will be facing serious water shortages or have no water all.

In the interest of sustainable water use, Africa has to devise effective ways of dealing with the pertinent economic (Economic change in Africa), social and ecological challenges. The economic challenge pertains to maximizing social and economic benefits from available water resources, while ensuring that basic human needs are met and the environment is protected. The growing competition between water users has to be effectively managed, and water disputes and conflicts avoided or adequately resolved. The social challenge is to ensure equitable access to safe water. This should be complemented by actions focused on reducing the vulnerability of poor people (especially women and children) to health hazards associated with water pollution. Meeting this objective requires that sufficient and priority attention is paid to the rehabilitation of water-supply systems destroyed by conflict or water-related disasters (floods, droughts). And, the ecological challenge is to ensure sustainable water use in terms of protecting the quality and quantity of the water resource in order to safeguard the needs of future generations.

These challenges become even more complex given that much of Africa’s freshwater resources are transboundary. Africa has 50 significant international river basins, each of which is shared by two or more countries. For 14 countries their entire territory is within international river basins. There are at least 83 river and lake basins shared by a number of countries: 11 in Northern Africa; 29 in Western Africa; 8 in Central Africa; 20 in Eastern Africa; and 15 in Southern Africa. Africa has a number of significant lakes. Lake Victoria is the largest tropical lake and the second largest freshwater lake by surface area in the world. With the potential negative impacts of climate change on the region’s water resources, freshwater stress and scarcity are likely to continue to be major issues.

Policies and legislative and institutional responses at the national and sub-regional levels have been adopted to deal with these challenges. Cooperation, decentralization, privatization and integrated water resources management (IWRM) have been strategies adopted in pursuit of sustainable water resources management. The adoption of cooperative approaches, such as establishing river basin organizations and action plans, have been critical in moving towards a more sustainable, fairer and equitable regime for transboundary management. River basin organizations, over the years, have encountered serious problems, including: lack of strong, sustained political commitment from member states; overly-ambitious programming and lack of focus on priority areas; administrative, managerial, technical, and financial problems; and political instability and civil strife.

Outlook

Freshwater issues have been on the regional and international agendas for many decades and will remain so for many more decades as demand on the resource grows. African

governments established the African Ministerial Council on Water (AMCOW) to provide regional leadership and strategic responses to the challenges of providing safe water and sanitation to the growing population. The role of AMCOW, along with other sub-regional and regional organizations, individual governments and civil society organizations, will continue to evolve as demands on managing the resource change. Water stress and scarcity, transboundary water resource management, irrigation expansion, pollution, climate change and other factors demand responses in the short, medium and long term.

The challenges are massive but not insurmountable. In terms of access to safe water and sanitation:

- An additional 405 million people must have improved access to safe drinking water by 2015, from January 2004, an average of more than 36 million each year, 690,000 each week.

- An additional 247 million people must have improved sanitation by 2015, with an average of more than 22 million every year, 425 000 peopleevery week, from January 2004.

While Northern Africa had by the beginning of 2005 met the Millennium Development Goal (MDG) target to “halve the proportion of people without improved drinking water in urban areas,” the rest of Africa had not registered any change. In the short term, most of Africa will continue to lag behind in terms of trying to meet the MDG targets on access to safe water and sanitation in urban and rural areas. Debt relief along with national-level responses may improve the opportunities for meeting these targets.

This may, for example, include more effective management of transboundary water resources through the rationalization of the multiple institutional arrangements, guided by the principles of equitable rights and sustainable and efficient water use. At the inaugural meeting of the African Ministerial Conference on the Environment (AMCEN) in Cairo in 1985, the ministers placed water issues high on the agenda for regional cooperation. They encouraged the establishment of regional technical cooperation networks on environment to adopt, among other objectives, “comprehensive soil and water development and conservation measures in irrigated and rain-fed agricultural areas in Africa” (AMCEN 1985). Many such networks are at work involving governments, sub-regional and regional organizations as well as the UN system. These networks can provide an effective basis for action.

Action

The objective of action should be “an Africa where there is an equitable and sustainable use and management of water resources for poverty alleviation, socioeconomic development, regional cooperation, and the environment”. This requires action at multiple levels, within different time frames. (Irrigation targets are dealt with under the preceding section on land.) The following are some of the many necessary types of urgent policy action:

- Ensure that water safety and sanitation issues remain key areas for attention. The Africa Water Vision 2025 sets the target to reduce by 75 percent the proportion of people without access to safe and adequate water supply by 2015. By 2025 this should be reduced by 95 percent. And by 2015, the proportion of people without access to safe and adequate sanitation should be reduced by 70 percent. By 2025 this should be reduced by 95 percent.

- Promote integrated water resources management (IWRM) strategies, including water harvesting technology. Under the Africa Water Vision 2025, African countries agreed to aim to implement measures in all countries to ensure the allocation of sufficient water for environmental sustainability, as well as measures to conserve and restore watershed ecosystems by 2015. By 2025 this should be extended to all river basins.

- Promote water re-use and recycling, and encourage introduction of necessary wastewater treatment before release into the environment.

- Harness water resources for hydropower generation, tourism, and industry to enhance the process of development, while at the same time ensuring that comprehensive environmental impact assessments are conducted. By 2015, countries should aim, as per targets set in the Africa Water Vision, to realize 10 percent of the development potential of water for these sectors, and by 2025 to increase this to 25 percent.

- Mainstream freshwater issues in all development initiatives to facilitate effective, efficient and equitable use, and properly value its contribution to sustainable development.

- Develop national, sub-regional and regional strategies for climate change adaptation to minimize its potential negative impacts on freshwater resources.

- Strengthen early warning systems through working closely with UNEP and other relevant organizations to mitigate the effects of extreme weather events such as droughts and floods.

Stakeholders

The stakeholders are governments, the private sector, communities, non-governmental organizations and civil society.

Result and target date

The result should be effective management of the resource which ensures improved access to safe water and sanitation to people in Africa, builds the resilience of people to overcome the impacts of extreme weather events and other disasters, and enhances food production to alleviate hunger. The target dates are 2015 and 2025, but water issues will continue to be an ongoing challenge for people in Africa and their governments.

Further reading

- AMCEN, 1985. Resolution adopted by the conference at its first session.African Ministerial Conference on the Environment. UNEP/AEC 1/2: Proceedings of the First Session of the African Ministerial Conference on the Environment, Cairo, Egypt, 16-18 December.

- Curtin, F., 2003. On the water front. Times Educational Supplement, 14 March.

- ECA, 2004. Assessing Regional Integration in Africa. ECA Policy Research Report. Economic Commission for Africa.

- ECA,AU and AfDB, 2000. The Africa Water Vision for 2025: Equitable and Sustainable Use of Water for Socioeconomic Development. Economic Commission for Africa, African Union and African Development Bank.Addis Ababa.

- Giordano, M.A. and Wolf, A.T., 2003. Transboundary Freshwater Treaties. In International Waters in Southern Africa (ed. Nakayama, M.), pp. 71-100. UNU Series on Water Resources Management and Policy. United Nations University Press,Tokyo.

- UN, 2002. Water Year 2003: International Year Aims to Galvanize Action on Critical Water Problems. Press Release. DPI/2293A. United Nations Department of Public Information, New York.

- UNEP, 2003. Water Policy Challenges and Priorities in Africa. Background Paper. Pan-African Implementation and Partnership Conference on Water. United Nations Environment Programme, Nairobi.

- UNEP, 2006. Africa Environment Outlook 2. Nairobi, Kenya.

- UN Millennium Project, 2005a. Investing in Development – A Practical Plan to Achieve the Millennium Development Goals. Earthscan, New York.

- UN Millennium Project, 2005b. Lack of Access to Water and Sanitation Hampers Efforts to Reduce Poverty in Developing Countries.

- UN Millennium Project, 2006. Fast Facts:The Faces of Poverty.

- WWF, 2004b. Living Planet Report 2004.WWF–World Wide Fund for Nature, Gland.

|

|

| Disclaimer: This article is taken wholly from, or contains information that was originally published by, the United Nations Environment Programme. Topic editors and authors for the Encyclopedia of Earth may have edited its content or added new information. The use of information from the United Nations Environment Programme should not be construed as support for or endorsement by that organization for any new information added by EoE personnel, or for any editing of the original content. |