|

Tea

Scientific name:

Camellia sinensis

Order/Family:

Theales: Theaceae

Local names:

Chai (Swahili)

|

Aphids (Toxoptera aurantii)

Aphids occur in groups on the buds and the undersides of young leaves. Large colonies of the aphids are mainly found feeding on seedlings causing leaf curl and defoliation They can be a major pest of tea in the nurseries. Additional damage is caused by production of honeydew, with subsequent growth of sooty moulds.

- Conserve natural enemies. Parasitic wasps and predators such as ladybird beetles, hoverfly and lacewing larvae are important in natural control of aphids.

- Whenever necessary spray attacked plants only (spot spraying). Laboratory experiments suggested that a neem-based product (Codrej Achook) formulated as wettable soluble powder, containing azadirachtin 0.03% (300 ppm) could be used for control of the citrus black aphid when applied at concentrations of 10 and 20% (Sudoi, 1998)

© Magnus Gammelgaard

Aphids

Parasitise…

Armillaria root rot (Armillaria heimii)

The fungus is confined to the soil and is normally a saprophyte living on dead stumps and roots of forest trees. However, if the root surface of the tea bush is damaged by cultivation or boring insects, the fungus can enter the roots and become parasitic. Leaves of affected bushes turn yellow and fall and sheets of white mycelium (fungal growth) can be found between the bark and the wood. The main root system rots away and the tea bush eventually dies.

- During land preparation stumps, pieces of wood and roots of forest trees must be removed from the soil.

- If Armillaria occurs in established tea, diseased trees must be thoroughly removed so that they do not become a source of infection for the neighbouring bushes.

Branch and collar canker (Phomopsis theae)

The first obvious symptom of attack is yellow or brown foliage on affected branches or bushes, contrasting with the green foliage of the surrounding healthy bushes. Closer examination reveals lesions or cankers at the base of branches or at the collar region of the bush. These lesions are less apparent in the early stages of infection but older cankers are easily recognisable by their raised margins due to the development of callus.

The diseased areas may be regular or irregular in shape, often sunken, and grey to black in colour. The underlying dead wood can be seen by scraping back the bark using a knife. In instances where the branch or the collar is completely girdled (ring-barked), a thick ridge of callus forms at the upper margin of the canker. The fungus can also infect apparently uninjured succulent green shoots, causing small local lesions. This can lead to the death of the whole shoot. Tea plants are most susceptible when they are less than 8 years old.

The disease is enhanced by drought conditions, deep planting, planting in gravelly soils, mulching close to the collar, wounds by weeding implements, low moisture status in the bark and surface watering during dry weather.

- Use resistant varieties, if available, particularly in areas with a history of the disease.

- Plant only healthy, vigorous plants with a well-developed root system.

- Avoid planting in poor soils and in areas where rainfall is marginal or inadequate.

- Mulch the soil towards the end of the rainy season to prevent it drying out too quickly.

- Plants should be treated lightly (light plucking) during propagation and nurturing.

Brown and grey blight (Colletotrichum coccodes and Pestalotiopsis theae)

These fungi are considered weak pathogens and usually only affect plants that have been weakened by improper care or adverse environmental conditions. Often they occur together.

The diseases are favoured by poor air circulation, high temperature, and high humidity or prolonged periods of leaf wetness. When young twigs of susceptible cultivars are cut and used to root new plants, latent mycelium (fungal growth) in the leaf tissue may start to invade nearby cells to form brown spots, and this may lead to death of leaves and twigs.

Symptoms consist of small, oval, pale yellow-green spots first appearing on young leaves. Often the spots are surrounded by a narrow, yellow zone. As the spots grow they turn brown or grey, concentric rings with scattered, tiny black dots become visible and eventually the dried tissue falls, leading to defoliation. Leaves of any age can be affected. The tiny, black spots on the lesions contain the fungal spores. Rain splash transports the spores from one plant or site of infection to another. If the spores land on a leaf, they germinate to start a new leaf spot or a latent infection.

- Avoid plant stress.

- Grow tea with adequate spacing to permit air to circulate and reduce humidity and the duration of leaf wetness.

The cotton Helopeltis or mosquito bug (Helopeltis schoutedeni)

It is a slender, delicate bug up to 10 mm long with very long antenna, nearly twice as long as the body. The nymphs are yellow with pale red markings. The adults have a red body with blackish antenna, head and wings. The eggs are white and about 1.7 mm long, and are laid into soft plant tissue.

Nymphs and adults feed on young plant tissues, injecting toxic saliva into the plant during sucking, causing necrotic patches, seen as dark brown spots, on leaves and stems. Spots exude moisture from a central puncture when squeezed. As a result the leaves are twisted and the shoots can be severely stunted. Die-back of young shoots is common under heavy attack. This bug is a common tea pest in all East African countries.

- In India neem products (e.g. 'Neemark') are recommended for control of the tea mosquito bug (Helopeltis antonii)

© F. Haas, icipe

Crickets

Crickets are fat, brown insects, 2 to 5 cm long. The front legs of the mole cricket are broad and curved adapted for digging. Many crickets live in burrows in the soil. Adults and nymphs of the tobacco cricket (Brachytrupes membranaceus) and the African mole cricket (Gryllotalpa Africana) are nursery pests. They cut seedlings and drag them into underground burrows, or left them on the surface wilting for a few days before taken them into the burrow.

The tobacco cricket may be a sporadic pest, particularly on light sandy soils where the adult crickets can easily burrow. The African mole cricket can be a pest especially at low altitudes, and particularly in moist soil.

- When control is required, bran bait mixed with insecticide allowed in organic is generally effective.

© Adrian Pingstone, wikipedia

Cutworms (Agrotis segetum)

Caterpillars of the common cutworm occasionally attack seedlings by feeding on the roots and cutting off the stems.

- Eliminate weeds early, well before transplanting.

- Plough and harrow the field to expose cutworms to natural enemies and desiccation.

- Dig near damaged seedlings and destroy cutworms.

- Conserve natural enemies. Parasitic wasps and ants are important in natural control of cutworms.

© A.M. Varela, icipe

Nematodes (Meloidogyne spp., Pratylenchus brachyurus and Radopholus similis)

In some areas, nematodes reduce yields. Root-knot nematodes (Meloidogyne spp ) can be a problem in nurseries. Infested roots develop knots or galls. They later die and devoid of lateral roots. Affected plants show chlorosis and stunted growth.

- Remove infested tea bushes, remove and replace large amounts of the soil.

- Use nematode-free planting material.

- To prevent infestation use plant-bags in the seedbed and use shade tree Indigoferra teismanii (Indigo tree) as a trap plant.

- Also sow Guatemala grass (Tripsacum laxum) before starting a new plantation to suppress weeds, which could harbour nematodes.

- Another important non-chemical method of control is the use of resistant or tolerant clones, if available .

- Incorporation of neem cake into the soil is an effective management measure.

© A. M. Varela, icipe

Scales

Scales are 1.0 to 7 mm long, usually green, yellowish or brown in colour and resemble shells glued to the plant. Female scales have neither wings nor legs. Females lay eggs under their scale. Some species give birth to young scales directly. Once hatched, the tiny scales, known as crawlers emerged from under the protective scale. They move in search of a feeding site and do not move afterwards. They suck sap on leaves and twigs. Their feeding may cause yellowing of leaves followed by leaf drop, poor growth, and dieback of branches. Two types of scales attack tea: soft and armoured scales.

Soft scales (Coccus spp; Saissetia coffeae) infest leaves and twigs. They cause damage by sucking sap from the plant and by excreting honeydew, causing growth of sooty mould. In heavy infestations leaves are heavily coated with sooty mould turning black. Heavy coating with sooty mould reduces photosynthesis and affects the quality of the leaves. Ants are usually associated with soft scales. They feed on the honeydew excreted by soft scales, preventing a build-up in sooty moulds, but also protecting the scales from natural enemies.

Armoured scales (Selanaspidus spp and Aspidiotus destructor) encrust foliage, the cause damage by sucking sap; they do not excrete honeydew.

- Conserve natural enemies. A large range of parasitic wasps and predators attacks scales. These natural enemies usually control scales. Outbreaks are generally related to the use of broad-spectrum pesticides that kill natural enemies, and or to the presence of large number of ants. If ants are protecting scales, try to control the ants by destroying their nests or spraying with soap mixed with water.

- Check infestation by scales. Peel off the hard shields and check whether there are living insects underneath. Dead empty shields can remain glued onto the plant for months, making it look like the scale population is much higher than it really is.

- If large numbers of living scales are present spray with light mineral oils. Sprays should target young stages of the scales. However, note that at high concentrations, mineral oils may be harmful to the plants. Oils should not be sprayed during periods of excessive heat or drought.

- At early stages of an outbreak cut and burn infested twigs and leaves.

© A. M. Varela, icipe

Armoured s…

Armoured s…

Tea mites and spider mites

Mites are among the major pests of tea. Sporadic yield losses in the affected areas in Kenya are estimated to be about 50%. Growth of young tea is reduced by mites by about 30%.

1) The red crevice tea mite (Brevipalpus phoenicis)

They are also known as the false spider mites or the scarlet mites. They attack leaves of all ages, distorting them. They feed on the undersides of leaves, especially between the main veins at the petiole end. Corky areas are formed on the underside of leaves, especially between the main veins at the petiole end of leaves; attacked leaves may dry up and be prematurely shed; they may cause serious defoliation, resulting in reduced yield.

Numerous tiny red mites can be seen in the bark crevices of the new wood. A few bushes may be heavily attacked, leaving the majority almost free from attack. This mite is a major pest of tea, causing heavy damage especially in prolonged drought. It occurs in all growing areas in Kenya, being serious around the Mount Kenya region (Sudoi et al., 1994).

2) The tea red spider mite (Oligonychus coffeae)

It is also called red coffee mite. It may cause considerable losses to tea production. Mite attacks are usually confined to few bushes. These mites are reddish brown and purple. They feed together on the upper surfaces of the leaves, the cast skins of the immature stages remain stuck on to the leaf and maybe seen with the unaided eye as irregular white spots. The upper surface of fully hardened leaves turns yellowish brown, rusty or purple colour. If the tea bush is under drought stress, flush leaves may also be attacked. They usually prefer older leaves but in heavy infestations younger leaves maybe attacked. This mite has been recorded in all tea growing areas in Kenya in low to moderate infestations (Sudoi, 1991).

For more information on spider mites click here.

3) Yellow tea mite (Polyphagotarsonemus latus)

It is also known as broad mite. It is a minute mite yellowish to whitish in colour and cannot be seen with the naked eye. This mite is a sporadically serious pest in tea nurseries, and has been reported as a common pest of tea in Tanzania (Bohlen, 1973).

Attacked leaves remain small, are crinkled, or otherwise distorted with corky brown areas between the main veins on the underside of the leaf. The plants are severely stunted in case of serious infestations.

- Use neem extracts in emergencies. Sudoi (1998) found that although neem seed oil at a rate of 0.03% was not satisfactory on contact against the tea red spider mite, direct application on the pest at 2.5% significantly reduced its survival. Thus, he considered that neem products have potential against spider mites in tea nurseries and in the field. In India, neem oil and commercial neem products ('Neemguard', 'Repelin' and 'Biosol') significantly reduced broad mites on chilli (Ascher et al., 2002).

- Till weeds early enough before the main harvest begins.

- Use resistant clones, if available. It has been observed that certain clones suffer more attack by red spider mites than others during an outbreak of the mites. Thus, clone "7/9" is less suitable for red spider mite development. Certain clones, like "SFS 150" and "6/8", exhibit resistance to the red crevice tea mite (Sudoi, 1992).

- Provide good growing conditions, healthy plants are more likely to withstand mite attack. Studies in the Eastern Highlands of Kenya showed that nitrogen fertilisation increased plant vigour and induced tolerance to attack by the red crevice mite (Sudoi et al., 2001).

© Image supplied by Warwick HRI, University of Warwick.

Spider mit…

Spider mit…

Tea weevils (Aperitmetus brunneus, Entypotrachelus meyeri)

Adult weevils feed on the foliage and chew the leaf edges and also bore irregular holes through the leaf surface. The larvae are the most destructive, feeding on the taproot and causing wilting, stunting, and eventual death of young plants. Stems of young plants may be bark-ringed at ground level by the larvae.

In Kenya, the tea root weevil (Aperitmetus brunneus), which is about 7-9 mm long with pale grey scales on its body, is considered a serious pest in tea nurseries. Losses of 30 to 40% are common. The tea weevil or Kangaita weevils (Entypotrachelus meyeri) occasionally defoliate young tea newly transplanted to the field.

- Laboratory experiments suggested that a neem-based product Godrej Achook formulated as wettable soluble powder, containing 0.03% (300 ppm) azadirachtin has an antifeedant effect on the tea weevil (E. meyeri) (weevils stop feeding or eat less) when applied at concentrations of 10 and 20% (Sudoi, 1998).

Termites (Odontotermes spp., Microtermes natalensis, Pseudocanthotermes militaris)

Termites feed on woody roots, branches and stems. The most damaging termites are those that attack living wood. They enter through the roots and work their way upward, finally destroying the heartwood. Stem beneath the soil is ring barked and the entire root system may be destroyed. Above-ground symptoms include wilting leaves and a poorly-growing plant. They occur most frequently on newly established plantations. Severely attacked plants wilt and die. Older plants may shed leaves. In most cases only a few plants are affected. Damage by termites to roots and stems of older plants can assume economic levels. A heavy infestation of termites that attack live wood can reduce yields by 10-15%. It may even kill large mature tea bushes. Termites that eat only dead wood do not cause direct damage, but they may make the plant more susceptible to fungal diseases.

- Remove stumps and dead trees (including their roots) when clearing land to plant a new tea field.

- Monitor crop regularly. Once a tea bush becomes infested, observe if the termites are eating living wood or only dead wood (wood already killed by sunscorch, die-back after pruning, or diseases).

- If the termites are eating living wood spray with an accepted insecticide. Neem products are reported to control termites. At pruning time, cut the branches back so that you expose at least 2 openings into the nest inside the trunk. Then, spray the insecticide into the nest. Spray immediately after pruning, because the termites will quickly block up the openings with mud.

- Dig up and burn infested bushes, and replant. Before replanting, check to make sure that neighbouring bushes are not infested.

- If the termites are eating only dead wood, prune off infested branches and clean away any sawdust or mud tunnels from the surface of the tree.

- If possible, find and destroy the nests (nests will be located in the soil or in a dead tree).

© A. M. Varela, icipe

The black tea thrips (Heliothrips haemorrhoidales)

The adult thrips are about 1.5 mm long and dark brown or black in colour with whitish legs, antenna and wings. The nymphs are whitish or greenish in colour. They feed on leaves of all ages.

Attacked buds are small, crisp and are brittle (easy to break). When the damaged bud unfolds, the leaves have a brown line of dry scars (like cork) along either side of the main rib. Yellow mites cause similar corky lesions, but thrips feeding usually does not cause the leaves to curl up like yellow mite. Even a few thrips feeding on a bud can lower the quality of the bud, making the dried buds brittle and the processed tea bitter.

Attacked leaves show silvering and a fine speckling of black spots, which are the excreta of the thrips. Damaged, leaves become thicker and harder than the normal ones, duller (not shining) and having darker green colour, and may be puckered or deformed. Thrips may also feed on the surface of stems, but only near the tip of a young shoot. This stem feeding causes rough, brown dots or patches on the surface of the stem. A tea bush with many thrips is often stunted and dry. Thrips can cause economic damage mainly in periods of drought.

- Provide favourable growing conditions for the crop. Thrips are often a bigger problem in old, stunted and dry tea fields. A strong tea crop can tolerate thrips Tea plants often grow out of the damage quite quickly if well tended. In particular adequate irrigation is a critical factor in minimising damage.

- Use shade to increase humidity in regions with extensive dry seasons. Thrips are favoured by dry and hot weather conditions. Planting shade trees is one of the best ways to reduce thrips populations in dry conditions.

- Pluck frequently to remove thrips and their eggs. Because thrips feed mostly on buds and the youngest leaves, plucking can greatly reduce the number of thrips. Frequent plucking reduces thrips more than plucking only once a month.

- Conserve natural enemies. Predatory mites and pirate bugs are important for the natural control of thrips. For more information on natural enemies click here

© A.M. Varela, icipe

Wood rot (Hypoxylon serpens)

Wood rot in tea has been reported from several countries including India, Kenya, Malawi, Zimbabwe and Sri Lanka. The pathogen implicated is Hypoxylon serpens. Significantly, all affected areas lie at or above 1500 m.

The characteristic symptoms normally appear when the bushes are about 15 to 20 years old. Suddenly, the foliage of a branch will show wilting followed by scorching. Such branches snap off easily near the base. Sometimes intact lower branches with green foliage in these bushes could snap off similarly, especially when workers walk through during field operations. The bases of such branches have characteristic black encrustations (stroma - fungal fruiting bodies containing spores). The pathogen appears to be disseminated mainly through pruning knives and the infection progresses from pruning cuts during wet weather. Under natural field conditions, infection at 60-90% and over 90% could bring about 27 and 36% yield reductions, respectively, showing that the disease can cause significant damage.

- Plant resistant clones, if available.

- Avoid pruning of tea bushes and rejuvenation pruning during dry weather.

| General Information and Agronomic Aspects | Information on Weeds | |||

| Information on Pests | Information Source Links | |||

| Information on Diseases |

|

| Geographical Distribution of Tea in Africa |

In Kenya tea ranks as the second most important cash crop in terms of foreign exchange earnings and is grown both in large estates (total hectares in 2005: 48,800) and by small holders (total hectares 2005: 88,000) with a total production in 2005 of 324,700 tons at a price of 12,696 KSh per 100 kg bag of black tea.

Tea is used worldwide as a beverage after infusion of the leaves in hot water. Primarily, tea is drunk as black tea. But in East Africa tea is mixed with milk and commonly referred as white tea. Recently, organic green tea and instant tea are manufactured in increasing quantities.

In regions with extensive dry seasons, shading trees play an important role in providing and maintaining sufficient humidity. Additionally, tea plantations in windy regions should also be protected by windbreaks (see below), to reduce the intensity of evapo-transpiration.

Tea performs best in soil of volcanic origin. Areas with bracken (ferns) are indicators of suitable ecology. The soil should be deep (1.8-2.0m), well-drained and aerated. Nutrient-rich and slightly acidic soils are best (optimum pH-value 4.0-6.0). Outside this range, basic nutrients are rendered immobile, i.e. above pH 6, calcium restricts the uptake of potassium and below pH 4, phosphorus is fixed (locked in).

Sufficient drainage and aeration of the soil can be lastingly and economically achieved with the combination of shading trees and deep-rooting green manure plants. China tea (C. sinensis var. sinensis) is especially suited to hilly regions. It is resistant to drought, and can tolerate short periods of frost (yet has a low tolerance of shade). Contrastingly, Assam tea (C. sinensis var. assamica) is a purely tropical crop, and reacts sensitively to drought and cold (yet has a high tolerance of shade). With a slope of above 30°, expensive soil conservation measures will be necessary. If terraces are dug, they should be 1 m wide at 2 m vertical intervals and also have a 1:30 gradient for drainage.

- Old clones include: "6/8", "7/9", "12/12", "31/8", "100/5", "7/3", "11/4", "12/19", "31/11" and "108/82"

- 1986 releases include: "54/40", "303/178", "302/216"

- 1988 releases include: "31/27", "31/29", "55/56", "303/2592, "55/55", "30/199"

- others: clone "7" and "15/11"

- Tea seed production.

- Tea breeding.

- Tea seed nurseries.

- Clonal selection.

- Vegetative propagation.

- Site should be well sheltered from prevailing winds.

- Site should be exposed to sunlight for developing plants to benefit from the sun's warmth (i.e. in cold areas like Kericho and upper areas of Central Kenya).

- In hot areas site needs some protection from the full heat of the sun. Suitable shading trees include Crotalaria spp. and, Sesbania spp. (both fast growing and able to fix nitrogen).

- Avoid low lying areas which get very wet during rainy seasons or frost during dry months.

- Site should be near a reliable water source.

2. Nursery soil

- Site should be near suitable source of soil.

- Soil to be used in sleeves can be transported to the nursery.

- Top soil should have a pH of 5.5 while subsoil should have a pH of 5. Cuttings will not root in soil with a pH higher than 5.5. Test both topsoil and subsoil for pH if it is being used the first time.

- Avoid subsoil with a high clay content as it will have poor drainage.

- Rooting of cuttings is also hampered if the soil has a high organic matter content (humus).

- Cuttings should therefore be rooted in subsoil or in soil from below long established grass.

- After establishment roots should eventually get access to a more fertile soil.

3. Nursery fertiliser guidelines

- Cuttings should be planted in a layer of subsoil about 7.5 cm deep, containing 600g/m³ rock phosphate and 300-500 g/m³ wood ashes (containing potassium) or in polythene sleeves containing the same.

- Beneath this subsoil (cap) or sleeve, enrich rooting medium by mixing with topsoil and additional fertiliser similar to above application. On grassland soil and exhausted soil, the site should be prepared with legumes 1 year ahead, e.g. with Crotalaria spp., Tephrosia candida that are afterwards mulched and worked into the subsoil and above cap added on top before planting.

- Do not compact the surface of the lower rooting medium to ensure transitional layer between it and the sub-soil cap or sleeve

- Soil used in the nursery may be heated to 60°C for killing the infective juveniles of root knot nematodes (see also "solarisation")

4. Sleeve Nurseries

They are easier to transfer to planting holes than uprooted plants. Size of sleeves depends on size of plants required by the grower - larger plants need larger sleeves.

Cuttings in large sleeves are more widely spaced and have better lateral shoot growth. Large sleeves imply fewer plants raised in each bed which is expensive. Sleeves should be spot sealed or stapled once in the middle of the bottom edge to help hold the soil and allow for drainage. Excess water is drained by punching a few holes near the bottom edge. Fill sleeves with soil mix described above, from which all roots, hard soil lumps and stones are removed up to a height of 17.5-18 cm. Pack soil firmly (not too hard) and let it be damp all the time, otherwise it will pour out of the sleeve. If soil in the sleeve is allowed to dry, it becomes difficult to wet later.

5. Nursery construction

Size of nursery depends on number of plants required by the grower and can range from 1000 plants to hundreds of thousands of plants. There are 2 types of nurseries (i) low shade nursery and (ii) high shade nursery. For details of construction please contact nearest Agriculture Extension Office.

6. Mother bushes

These should be pruned twice a year even if cuttings are needed only once a year in order to get highest quality material. Time of pruning depends on the time cuttings are to be propagated: for propagation in September, mother bushes should be pruned February to March.

New stems should never be allowed to remain on mother bushes for more than 7 months, as the material then gets too hard and produces poorly growing cuttings. Mother bushes should not be covered. If the mother bushes have aphids, these should be eliminated ahead of pruning for cuttings.

7. Preparation of cuttings

Prunings (cut branches) are wrapped in wet sacks and taken to a nearby shelter (shade) where they are watered immediately. They should be kept shaded at all stages thereafter. Cuttings are made from young shoots (5-7 months old), which are vigorously growing. Discard (trim off) the very soft tips (those that are smashed when pressed in between 2 open fingers and thumb) and the very hard lower parts of branch where bark is forming.

|

| © AIC, Kenya 2002 |

Make cuttings consisting of a 1 leaf with 3-4 cm of stem below the leaf as shown on above diagram. Make 1 cut just above the bud and sloping away from bud with a sharp knife. Make second cut across the stem 3-4 cm below the bud and also a sloping cut.

Place cuttings immediately in a container full of water and let soak for about 30 minutes before planting. Place each cutting as in the drawing above making sure neither leaf nor bud is touching the soil. The bud should be just above the soil surface. Do not touch the top or buttom (ends) of the cutting as the sweat from the fingers may affect survival. Keep the cuttings moist during planting by regular light watering.

NB: Strong water jets displace cuttings. Shade the cuttings by spreading a clear polythene sheet over the nursery bed, forming a dome shape and tacking it into the soil.

After planting care: All beds should be inspected at least once a week. A heavy condensation should be found on the under surface of the polythene sheeting (enough to mar clear view). If there is only a little condensation, it means the soil in the sleeves is too dry or sheeting is torn or seal is poor. Such faults should be corrected immediately. Remove weeds by hand pulling and replace the shade. In hotter areas a more dense shade may be necessary.

Hardening off: Plants grown under polythene sheeting and shade are soft and will be scorched to death if sheeting is removed too quickly. Hardening off starts as soon as new shoots are 20 cm (8") tall. During the first 4 weeks, the polythene is gradually opened and raised on the side away from prevailing winds. First week open polythene a bit every 3 m and support by a stake. Second week the vents are doubled by making similar vents every 1.5 m.

Soil in the sleeves should not be allowed to dry, so watering is done through the vents with a hosepipe. Third week the whole sheeting is completely rolled upon the vent side, leaving only 1 side of the bed covered and at the fourth week polythene is removed completely, washed thoroughly and stored away from sun and rodents for later use.

Two weeks after removal of polythene the shade frame is raised 30 cm (1 ft) on 1 side only and supported by stakes. After this it is raised 30 cm every week for 3 weeks and then completely removed. Plants must be watered as necessary and foliar feed applied weekly until they are transplanted.

NB: If the weather changes and gets suddenly dry and plants start scorching, hardening off should be postponed or beds recovered.

The cuttings of these leguminous plants or those of Guatemala grass (Tripsacum laxum) placed alongside the tea plants also serve to provide mulch for moisture conservation and to control erosion and weed growth.

Other crops, which can be used in a young tea plantation, include oats, Napier grass or maize stalks. The mulch should not touch the stems of the tea, as this will encourage weevils and dusty brown beetles. Another advantage of mulching is the release of nutrients during decomposition of the mulch. The use of shade trees is restricted to low altitudes; the most important are Falcataria moluccana (syn. Albizia falcata, A. falcataria, Paraserianthes falcataria), Leucaena leucocephala and the December tree Erythrina subumbrans.

Mature tea is mulched with its own prunings.

Planting of wind breaks: Wind breaks should be put in place facing the prevailing wind. A row of tea could also be allowed to grow up as a wind break, or depending on the size of the field, tall or short trees can be planted about 3 m apart. Useful tall trees include pine, cypress and grevillea. Shorter windbreaks include bananas, and the willow-leaved Hakea (Hakea salign).

- On level ground, the distance between adjacent belts should be 10 times the effective height above the tea (e.g. the effective spacing of trees which are 10 m tall planted to protect tea plants which are 1,5 m tall will be 8.5 m (10-1.5) multiplied with 10 i.e. 85 m (8.5x10) or 85 m apart.

- On sloping ground the distance between adjacent belts should be less than this, but if the belts become too close the yields will be reduced by shading and also by competition with shelter trees

Older plantations may have depleted the soil of certain nutrients. If a soil analysis shows very low calcium levels, an application of gypsum is recommended, as this will provide calcium without increasing the pH. Also rock phosphate is an allowed fertiliser in organic systems; apply about 30 g/bush per year (2 tablespoons) as well as light sprinkling of any wood ashes available.

Bringing tea into bearing: During establishment of tea in an estate or smallholding, there is a period when financial returns may depend on the speed and efficiency with which the young tea is brought into bearing. Any operation designed to form a permanent branch system, from the time the plants are in the nursery to the time they are tipped in to form a plucking table in the field is defined as 'bringing tea into bearing'.

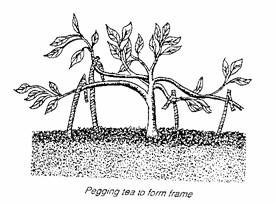

Frame formation: The lower parts of the bush will form the permanent frame which remains unchanged throughout the life of the bush or until the bush is cut down or 'collar- pruned' to rejuvenate it. This frame must be low, strong and have a good spread. In tea, a wide frame of branches is needed for the plucking table. The tea plant is cut back to 15 cm after being in the field for 12 months. When the new shoots reach height of 60-75 cm they are pegged down (when the reddish bark starts to develop near the main stem).

|

| © AIC, Kenya 2002 |

Pegging: The shoots that develop from a stump (explained above) or after the first light pruning of a sleeved plant are bent downwards and pegged so that they radiate outwards and upwards from the main stem. Pegged branches form the base of a permanent frame, which is an addition to the vertical shoots that develop from auxiliary buds among the branches. Development of these buds is encouraged by pegging the branches, so that they slope uniformly and slightly upwards. If pegging is done such that branches are horizontal or slope downwards, development of auxiliary buds is retarded or even stopped. Auxiliary bud development is further encouraged when two terminal leaves and buds are removed from the pegged branches during pegging. This activity removes growth inhibitors from the plant tip, which promote terminal growth and suppresses or inhibits lateral or auxiliary bud growth. This phenomenon is known as "apical dominance".

Plucking table formation: After the frame is formed shoots are allowed to grow for 3 months, and then their growth is checked by tipping (removing 3 leaves and bud from each shoot above the desired height). Plucking table should be 50 cm from the ground and tipping should be done 4-5 times before plucking starts.

Plucking: This is done to maintain the established tea, starting usually after 2 years. Routine picking is done at intervals of 5-10 days depending on growth. There are 4 types of plucking:

- Fine - plucking 1 or 2 leaves and a bud. A stick is placed on the tea table for guidance and shoots above it are picked (two leaves and a bud).

- Coarse - removal of 3 or more leaves and a bud.

- Light - pick leaving some new foliage above the previous plucking level.

- Hard - shoots are plucked right down to the previous plucking.

Plucked leaves must NOT be compressed in a basket as this will cause fermentation. Plucked leaves should be kept in the shade and taken to the factory as soon as possible and in good condition the same day. Leaf containers should NOT be placed on the soil. Dormant shoots with unopened central leaf are called Barijhi, they are hard and should be discarded. With correct plucking the plucking table rises some 10 cm every year. The finer the plucking, the better the quality of tea. Under plucking causes the table to rise very quickly and may render the plucking physically impossible by third year.

Pruning: This is the removal of a shoot from a tea plant. When soft apical shoots are removed as at tipping in to form a table, auxiliary buds are stimulated to develop for a distance of 10-12 cm below the cut. This development also occurs during hard pruning and during preparation of stumps from the nursery.

Any auxiliary shoot that develops outwards contributes to the spread of the bush. After 3 years, yields begin to decline and the plucking table becomes too high. It is then necessary to prune back. At each pruning the height should be increased by 5 cm above the previous pruning to avoid callous tissues.

After several prunings the bush should be cut right back to 45 cm. Pruning should be done parallel to the slope on steep land to avoid a step effect. In dry weather, prunings should be left on top of the bushes to protect the plants from sun scorch. Otherwise the prunings should be left between the rows to replenish the organic material and nutrients to the soil and to prevent erosion. It is best to prune only a third of the garden when due so as to keep up production.

The pruning cycle varies from every 2 years in tropical lowlands to every 3-5 years at higher altitudes. Pruning should preferably be done during a dormant period if there is one, e.g. immediately following dry weather in East Africa.

Organic fertilisation strategies

A. Litter fall and pruning material from shade trees

Litter is provided without any additional work. Additional working hours need to be calculated for pruning the shade trees (to create an ideal micro-climate, admit light and control the growth of the tea bushes). The pruning material should remain as mulch directly on the site, or, if applicable, be used as compost material. Yet if the pruning material is to be used as fuel, at least the ashes should be used as a compost supplement (e.g. to replace the potassium). Three aspects need to be heeded, in order to create the conditions necessary for the soil micro-organisms to efficiently decompose the pruned material: The material needs to be sufficiently chopped (2-5 cm pieces). The material must then be evenly spread around the tea bushes (avoid creating heaps of material). The carbon-rich material needs to be mixed with additional nitrogen-rich material (e.g. neem-press cakes, castor cake or green manure from crotalaria) in order to achieve a better soil environment for successful decomposition.

B. Green Manure (mulch)

The foliage from green manure plants, as well as that from the other crops, should remain as mulch material on the site. In the cases of tea gardens where integrated animal husbandry is practised, care should be taken to choose green manure plants that can also be used as fodder crops.

C. Composting and animal husbandry

The basic source of fodder for the animals comes from green manure plants (e.g. Guatemala grass) and vegetation in the tea garden's edges, which are not planted with tea, or from plants neighbouring the tea garden. The space available to grow fodder must be taken into consideration when calculating the number of cattle to acquire. If the nitrogen demand of the tea (on average around 60 kg) is to be met entirely from composted cattle manure, around 2 cattle per ha of cultivated tea are required. For this method, small ditches are dug between alternating plant rows every 3-4 years, and filled with pruning material, green manure plants, compost and cattle dung (the organic material must be well cut-up, and should not be buried too deep). Simultaneously, the tea bush roots are also cut to stimulate new growth. The disadvantage of this method is the high workload involved especially on older plantations with narrow gaps between the rows.

Yields

Annual yields of 1000 - 1300 kg/ha of processed tea or 5 times that amount of green leaf under good management are possible. An experienced plucker is able to pluck at least 30 kg of leaf per day. For tea bushes over 50 years old, it is necessary to monitor the yield level and percentage of gaps in individual fields. If yields are less than 1000 kg/ha of made tea in such a field it is a sign of stagnant production and call for rehabilitation. This can be done by rejuvenation pruning or replanting.

|

Tea mites and spider mites Mites are among the major pests of tea. Sporadic yield losses in the affected areas in Kenya are estimated to be about 50%. Growth of young tea is reduced by mites by about 30%. |

Spider mites

Predatory mites (Phytoseiulus persimilis) (orange-red), in a colony of two-spotted spider mites (Tetranychus urticae). Two-spotted spider mite adult females are 0.6 mm long. © Image supplied by Warwick HRI, University of Warwick. |

|

What to do:

|

|

The black tea thrips (Heliothrips haemorrhoidales) The adult thrips are about 1.5 mm long and dark brown or black in colour with whitish legs, antenna and wings. The nymphs are whitish or greenish in colour. They feed on leaves of all ages. |

Red-banded thrips

Immature stage of the red banded thrips (Selenothrips rubrocinctus). Note a bright red band across the abdomen of immature thrips. Real size: about 1mm long. © A.M. Varela, icipe |

|

What to do:

|

A wide variety of diseases have been reported on tea, but many of them are not of economical importance. One of the most serious diseases in major tea producing countries is blister blight caused by the fungus Exobasidium vexans, but this disease has not been reported in Africa. The major diseases in Africa are Armillaria root rot (Armillaria heimii) and wood rot (Hypoxylon serpens). Others like branch and collar canker (Phomopsis theae), brown blight (Colletotrichum coccodes) and grey blight (Pestaliopsis theae) are of variable importance. Root-knot nematodes (Meloidogyne spp.) could be a problem in the nurseries.

Weeds are problematic mainly in the new clearing and pruned fields and it is necessary to control them till the tea bushes cover the field. Certain cultural practices like mulching, raising cover crops, closer planting, higher pruning and tipping practices, infilling and manual weeding are important.

- AIC, Kenya (2002). Field Crops Technical Handbook.

- Acland J.D. (1980). East African Crops. An introduction to the production of field and plantation crops in Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda. FAO/Longman. ISBN: 0 582 60301 3

- Agricultural Information Center. Nairobi (2002). Field Crops Technical Handbook.

- Ascher, K. R. S., Manzor, M. and Mansour, F. A. (2002). Effect of neem on viruses and organisms.- Acarina: Mites. In The Neem Tree (Azadirachta indica A. Juss) and other Meliaceous Plants. Sources of Unique Natural Products for Integrated Pest Management, Medicine, Industry and Other Purposes. H. Schmutterer (Ed.). Second edition

- CAB International (2005). Crop Protection Compendium, 2005 edition. Wallingford, UK www.cabi.org

- Naturland e.V. www.naturland.de

- Republic of Kenya, Ministry of Agriculture: Economic Review of Agriculture 2006

- Tea IPM Ecological Guide. Michael R. Zeiss, Koen den Braber. Published by CIDSE, April 2001. www.adam-project-vietnam.net

- University of Hawaii, Cooperative Extension Service/CTAHR: Identification Guide for Diseases of Tea (Camellia sinensis) www.ctahr.hawaii.edu

- Upasi Tea Research Foundation www.upasitearesearch.org Coimbatore District, India

Back

Back