Sustainability and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency

This article focuses on sustainability with particular attention to the role of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. It outlines how the concept of sustainability has evolved in business and government, the role of science and technology in achieving sustainable practices, and why achieving sustainable outcome is more urgent today than in the past.

The United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED) in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, which occurs in June 2012 will be an effort to further develop and disseminate knowledge about planning and implementing sustainable development. Reflecting a closer link to economic development, one of the core themes for the Rio world conference is achieving a “green economy.” The 2012 Rio event comes on the 50th anniversary of the publication of Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring (1962), the 25th anniversary of the UN Brundtland Report, which launched international work on sustainable development (1987), and the 20th anniversary of the first Rio Earth Summit in 1992.

The transition to a sustainable society will require the convergence of four major elements:

- effective laws, policies, and regulations;

- advances in science and technology;

- green business strategies; and,

- public support and participation.

Contents

- 1 Introduction: Defining Sustainability

- 2 Evolving Concepts of Sustainability

- 3 The Urgency of Sustainability

- 4 Public Understanding of Sustainability

- 5 Science and Technology

- 6 Perspectives of Business and Finance Perspectives on Sustainability

- 7 Making Sustainability Operational in Government

- 8 Sustainability at the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency

- 9 Summary

- 10 References

Introduction: Defining Sustainability

The most common definition of sustainability calls for polices and strategies that meet society’s present needs without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs. The core pillars of sustainability are shown in Figure 1. Human well-being rests on the successful integration of these core aspects of sustainability (Holdren 2008):

- Environmental conditions and processes, including our planet’s air, water, soils, mineral resources, biota, and climate, and all of the natural and anthropogenic processes that affect them.

- Economic conditions and processes, such as production, employment, income, wealth, markets, trade, and the technologies that facilitate all of these.

- Sociopolitical conditions and processes, such as national and personal security, liberty, justice, the rule of law, education, health care, the pursuit of science and the arts, and other aspects of civil society and culture.

Figure 1. Three pillars of sustainable development A 2011 report on sustainability from the National Research Council (NRC) defined sustainability as both a goal and an approach to resources management (NRC 2011a). The goal of sustainability is to protect and enhance social, environmental, and economic assets so that they are available not only for the current generation, but also for many generations to come. To accomplish this in an increasingly inter-connected world requires new problem-solving approaches that take entire systems into account, rather than isolated components. It also requires considering cumulative effects that occur over long time scales.

Figure 1. Three pillars of sustainable development A 2011 report on sustainability from the National Research Council (NRC) defined sustainability as both a goal and an approach to resources management (NRC 2011a). The goal of sustainability is to protect and enhance social, environmental, and economic assets so that they are available not only for the current generation, but also for many generations to come. To accomplish this in an increasingly inter-connected world requires new problem-solving approaches that take entire systems into account, rather than isolated components. It also requires considering cumulative effects that occur over long time scales.

The task of integrating actions across these three pillars and translating sustainability goals into reality raises a number of practical questions:

- “What kind of government policies and business strategies can advance sustainability?”

- “What scientific tools and approaches are needed to put sustainability into practice?” and,

- “How can the general public as both consumers and investors support and contribute to sustainability?”

Evolving Concepts of Sustainability

Human impacts on planetary resources can have far-reaching and often unintended consequences (Marsh 1965). At a very fundamental level, human survival and well-being depend on the quality of the air we breathe, the land that produces our food, the rivers and aquifers that supply our water, and the many other natural systems that provide us with essential goods and services.

The concept of sustainable development has roots that are over a century old. The father of American conservation, Gifford Pinchot, was President Theodore Roosevelt’s chief forester. Roosevelt relied on him for advice to develop public land polices in the late 1890s. Pinchot’s believed that the forests should be made to serve the future of the nation as well as the present. Pinchot was an early advocate of sustainable development; in The Fight for Conservation, he wrote “the central thing for which conservation stands is to make this country the best possible place to live in, both for us and for our descendants” (Pinchot 1910).

Though the term was not used, the concept of sustainability was captured in the National Environmental Policy Act of 1970 (NEPA), which formally established as a national goal the creation and maintenance of “conditions under which [humans] and nature can exist in productive harmony, and fulfill the social, economic and other requirements of present and future generations of Americans” (U.S. Congress 1970). The NEPA specified four areas on which the federal government must focus (Fiksel et al. 2009):

- Long-term planning: “fulfill the responsibilities of each generation as trustee of the environment for succeeding generations”

- Well-being: “assure for all Americans safe, healthful, productive and esthetically and culturally pleasing surroundings”

- Widespread prosperity: “achieve a balance between population and resource use which will permit high standards of living and a wide sharing of life’s amenities”

- Resource Management: “enhance the quality of renewable resources and approach the maximum attainable recycling of depletable resources"

The concept of sustainable development was further articulated in the United States through a pair of reports prepared by the Council for Economic Quality and the Department of State: Global 2000 Report to the President (1980) and Global Future: Time to Act (1981). Both reports identified future global challenges and potential consequences with an emphasis on economic growth in the developing world. The 1981 report noted, “The key concept here is sustainable development. Economic development if it is to be successful over the long term must proceed in a way that protects the natural resource base of developing countries.” The document called for a national energy strategy and more emphasis on energy conservation and renewal of energy resources.

Internationally, the concept of sustainable development was defined in the United Nations Brundtland Commission Report as “economic and social development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” (World Commission on the Environment and Development, 1987). This continues to be the most commonly cited definition of sustainable development.

Sustainability gained further prominence at the 1992 Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro, where 179 nations endorsed Agenda 21. This document declared, “[t]he right to development must be fulfilled so as to equitably meet developmental and environmental needs of present and future generations,” and “[i]n order to achieve sustainable development, environmental protection shall constitute an integral part of the development process and cannot be considered in isolation from it” (United Nations 1982).

The preamble of Agenda 21 identified the same array of problems faced by society today:

Humanity stands at a defining moment in history. We are confronted with a perpetuation of disparities between and within nations, a worsening of poverty, hunger, ill health and illiteracy, and the continuing deterioration of the ecosystems on which we depend for our well-being. However, integration of environment and development concerns and greater attention to them can contribute to fulfilling basic needs, improving living standards, better managing and protecting ecosystems, and providing a safer, more prosperous future. No nation can achieve this on its own — but together we can—in a global partnership for sustainable development (United Nations 1992).

In preparing for the Rio+20 conference, the concept of sustainability is once again getting public attention with considerable emphasis on supporting a prosperous and green global economy.

The Urgency of Sustainability

The phrase “Green Economy” is being advanced internationally by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). The underlying aim of the green economy is to help countries foster economic growth and development while ensuring that natural assets continue to provide the resources and environmental services on which well-being depends.

The movement toward a green economy reflects the fact that current approaches to resource management (energy, water, and material use) are not sustainable, and the unintended consequences of many past choices have left many challenging environmental problems. Today human society is using more resources than at any other time in history (U.S. EPA 2009). This is resulting in disturbing trends – global warming and sea level rise, the growing scarcity of fresh water, loss of arable land and forests, and decreasing biodiversity – that could affect economic growth, human health, and social well-being.

The impacts of population growth and economic development are detailed in the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (2005), which found that 15 of 24 important global ecosystem services (Ecosystem Services) are being degraded or used unsustainably.

To stimulate and map progress sustainability, the UN in 2000 officially adopted a set of Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) (MDG 2000). The MDGs consist of eight overarching social, economic, and environmental goals and specific targets. Progress today (2011–2012) toward achieving these goals is mixed. Many regions are on track to meet many of the targets, but other regions – especially sub-Saharan Africa – are projected to fall short on most of them.

Commenting on the MDGs, John Holdren wrote, “While the MDGs appear ambitious in terms of the pace of improvement embodied in the targets, they are really very modest when viewed in terms of the immense shortfalls in well-being that would persist into 2015 and beyond even if the targets were met” (Holdren 2009).

New momentum to achieve these goals is furthered by international efforts on advancing a green economy. The UNEP Green Growth report sees a green economy as not only relevant to more developed economies but also as a key catalyst for growth and poverty eradication in developing nations, where in some cases nearly 90 per cent of the income of the poor is linked to nature or natural capital such as forests and freshwaters.

Ecological stresses will only increase as the global population grows. In less than 50 years, world population has risen from just over 3 billion to 7 billion, and is expected to reach 9 billion by 2050 (United Nations 2011). The population growth will occur overwhelmingly in the less developed countries, likely exacerbating the income gaps between rich and poor nations. As less developed nations strive to reach the living standards of industrialized nations, they will seek access to education, health care, energy, communication, and consumer goods. Their citizens will aspire to an improved quality of life, with adequate food, clean water, shelter, and transportation. These aspirations, coupled with the continuing high demand for resources by developed nations, will place severe pressures upon global ecosystems.

Hundreds of metrics and indicators have been used to describe the impacts of human development on the environment. One useful composite indicator is the Ecological Footprint developed by the Global Footprint Network (2010). The Network’s 2010 Living Planet report notes that humanity’s ecological footprint has more than doubled since 1966. Its calculations indicate that if every human today were living at the same level of resource consumption as in developed countries, we would need three or four planets with natural resources equivalent to Earth.

It is clear from current data that global society must learn how to reduce its environmental footprint while enhancing and maintaining prosperity and well-being. The inexorable growth of the global economy, interrupted by the 2007–2009 recession, may be bringing society to a “tipping point” at which continued indifference to sustainability problems could lead to serious economic and environmental outcomes.

Public Understanding of Sustainability

Public understanding of the growing environmental threats and possible tipping points is a vital element for achieving sustainability. As both government and the private sector organizations move towards adoption of sustainability principles and business practices, more opportunities will emerge for individuals to make sustainable choices. At the same time, as more individuals explore ways to build a sustainable future, they will generate creative new ideas that businesses and governments can implement.

However, the transition to sustainability relies on more than the gradual evolution of consumer awareness to exert a “market pull.” Many of today’s sustainability challenges are a consequence of market failures; in other words, markets do not assign sufficient value to critical natural resources such as fresh water. Shifting to a sustainable global economy will require profound changes that can only be accomplished through collaborative initiatives involving business, government, and citizens. Moreover, a strong science and technology foundation will be necessary to inform and enable these efforts.

Science and Technology

Scientific and technological innovation is a driver of change, and a critical element in achieving sustainability. The required scientific knowledge will come from many disciplines—including chemistry, biology, and physics as well as economic and social sciences. New approaches such as “transdisciplinary” research have been introduced to describe the fusion of multiple disciplines to generate new knowledge, which is important for advancing innovation.

One practical application of science for sustainability is in the area of green chemistry, which involves the development and use of chemicals that are less hazardous to human health and/or have a reduced environmental impact. Following the principles developed by Paul Anastas and John Warner (1998), many companies over the past 10 years have incorporated principles of green chemistry, including adoption of safer chemical substitutes and more benign chemical processes.

Applications of green chemistry in business can advance innovation, reduce risk to human health and the environment, and enhance national prosperity and well-being. A recent research report predicts that green chemistry “represents a market opportunity that will grow to $100 billion by 2020” (Pike Research 2011).

The National Science Foundation’s Advisory Committee for Environmental Research and Education has argued in a recent report (2009) that “[e]nvironmental science must move beyond identifying issues and toward providing a sound basis for the development of innovative solutions, effective adaption, and mitigation strategies.” The report added that to accomplish this goal “we urgently need to expand our capacity to study the environment as an integrated system that includes the human dimension” (Strafford et al 2009).

One step in that direction is the emergence of “sustainability science” which aims to link many scientific disciplines together to create an integrated systems approach to problem solving. Sustainability science has been described as “bending the curve”; that is, accelerating favorable trends, slowing harmful trends, understanding complex trends, and noting changes in direction and inflection that constitute significant departures (Kates 2005).

Sustainability science builds on several crucial ideas:

- Applying integrated systems thinking: This approach is especially important in assuring that pollutant emissions or impacts are not merely shifted from one medium to another. An air problem today should not become a water problem tomorrow.

- Anticipating and responding to growing stressors: Over the second half of the 20th century, while world population more than doubled, food production almost tripled, energy use more than quadrupled, and the overall level of economic activity quintupled. This creates new challenges for protecting human health and the environment from pollution and over-consumption of natural resources.

- Adopting a transdisciplinary approach to problem solving: Sustainability science is defined by the problems it addresses rather than by the disciplines it employs. It applies research and analysis that draws on relevant necessary science and social science disciplines. It aims to solve problems by having all stakeholders be part of the research planning, design, and implementation of results.

- Promoting Innovation: Many established approaches and practices are unlikely to provide pathways to the future. Stimulating and adopting new and innovative solutions, including new technologies, are necessary approaches to solving sustainability problems.

- Seeking realistic solutions: Going beyond just defining a problem, sustainability science brings together all appropriate tools and approaches to help find practical solutions to real-world problems. A key goal of sustainability science is helping decision-makers make better and more informed decisions.

- Advancing society’s resilience: Understanding the vulnerability and resilience of environmental, economic, and social systems is critical for establishing a sustainable society. The most common definition of resilience is drawn from the engineering sciences—the capacity to absorb disturbances and to return to a prior (relatively stable) state. A more appropriate definition, drawn from the ecological sciences, is that resilience includes the capacity not only to absorb disturbances, but also to adapt and reorganize into a system that retains or improves its functional capacity (Fiksel 2006).

Thesecentral ideas provide a basisfor scientific knowledge to help society make good decisions, a needidentified by the House Committee on Science report, Unlocking Our Future:

While acknowledging the continuing need for science and engineering in national security, health and the economy, the challenges we face today cause us to propose that the scientific and engineering enterprise ought to move toward center stage in a fourth role; that of helping society make good decisions. We believe this role for science will take on increasing importance, as we face difficult decisions related to the environment (House Committee on Science, 1998).

Perspectives of Business and Finance Perspectives on Sustainability

Green business practices are crucial for achieving global sustainability. Several factors are driving corporations to adopt sustainability practices, including global supply chain challenges, government regulations, consumer awareness, expanding economic opportunities, and realization that sustainable business practices increase shareholder value (Hecht 2009, Hecht 2011). Increasing shareholder value is achieved in two ways: First, sustainability can directly improve profitability by reducing capital and operating costs, increasing market share, and reducing the chances of business interruption. Secondly, sustainability can create strategic value by improving a company’s “intangible” value drivers, including reputation, brand equity, license to operate and ability to attract talent (Fiksel 2009).

It is encouraging that today business leaders see sustainability as the “mother lode of organizational and technological innovations” and increasingly realize that “there is no alternative to sustainable development” (Nidumolu et al 2009). Corporate sustainable business practices often begin with attention to production processes and extend to the entire product life cycle – from extraction of resources and processing of feedstocks, to transportation, logistics, distribution, and end-of-life asset recovery. The terms “green business” and “green products” typically refer to such practices (Fiksel 2009). Sustainability includes these green practices, but goes much further—it describes the fundamental relationship of a company to society and the environment. Sustainable business practices enhance competitiveness by addressing the broader needs and concerns of company stakeholders, including employees, customers, suppliers, regulators, advocacy groups, and the communities in which a company operates. In other words, sustainable companies are both environmentally and socially responsible.

Strategies that promote sustainability have been incorporated into the management principles of dozens of Fortune 500 companies – more of them based in Europe and Asia rather than in the United States (PricewaterhouseCoopers 2002). Companies such as General Electric, Procter & Gamble, Wal-Mart, and UK retailer Marks & Spencer have embarked on environmental initiatives “not because it is trendy or moral, but because it will accelerate [economic] growth” (Sullivan and Schiafo 2005).

The World Business Council for Sustainable Development has developed an ambitious agenda to assist global industries in moving toward sustainable growth. Its Vision 2050 report introduced the notion of a “green race” and outlined a “pathway that will require fundamental changes in governance structures, economic frameworks, business, and human behavior.” The report argues that these changes are “necessary, feasible and offer tremendous business opportunities for companies that turn sustainability into strategy” (WBCSD 2010).

In partnership with the Trucost and Sustainalytics environmental research firms, Newsweek has ranked corporations since 2009 based on their environmental policies and management systems. Trucost (http://www.trucost.com), which specializes in quantitative measurements of environmental performance and holds an extensive database on corporate environmental impacts, calculated an “Environmental Impact Score” for each company in the Green Ranking based on over 700 metrics, including greenhouse-gas emissions, water use, solid-waste disposal, and acid-rain emissions.

From the 2011 rankings, Newsweek judged that “Top-ranked companies are approaching green projects with increasing tenacity, even in this weak economy.” Of the companies identified, Newsweek notes, “the U.S. is trailing other parts of the world in the sustainability arena.” After IBM (No. 2 on the global list), there are 12 spots before the next American company (HP, No. 15 globally)” The ranking identifies key companies around the world including Europe, Australia, Brazil, India, Canada, Japan, and Mexico. The study suggests that the tendency of European countries to dominate reflects their longer history of a “tighter regulatory environment.”

In the finance sector, the Dow Jones Sustainability Indexes define corporate sustainability as “a business approach that creates long-term shareholder value by embracing opportunities and managing risks that derive from economic, environmental, and social developments” (DJSI 2011).

UNEP Financial Initiative (UNEP FI), a global partnership between UNEP and the financial sector, brings together over 200 institutions, including banks, insurers, and fund managers, that work together to understand the impacts of environmental and social considerations on financial performance.

The principles of the UNEP FI clearly show the link of economic development and sustainability. “We members of the financial services industry recognize that sustainable development depends upon a positive interaction between economic and social development, and environmental protection, to balance the interests of this and future generations. We further recognize that sustainable development is the collective responsibility of government, business, and individuals. We are committed to working cooperatively with these sectors within the framework of market mechanisms toward common environmental goals” (UNEP FI 2011). A UNEP FI meeting in 2011 brought together leading industry and banking sectors to discuss current global challenges and how best to advance sustainable economic growth.

Making Sustainability Operational in Government

U.S. federal agencies can and are required to work together to drive innovation in science and technology, in policies and market interventions, and in business models and practices that enable transformation to a sustainable economy. Two executive orders – one issued by President George W. Bush and the other by President Barack Obama– have attempted to make sustainability operational in managing government buildings and other facilities.

In 2007, President Bush signed Executive Order 13423, “Strengthening Federal Environmental, Energy, and Transportation Management,” which sets goals in the areas of energy efficiency, acquisitions, renewable energy, toxics reductions, recycling, sustainable buildings, electronics stewardship, vehicle fleets, and water conservation. This Order explicitly directs heads of federal agencies to implement sustainable practices in these areas, and specifies that “sustainable” means “creat[ing] and maintain[ing] conditions, under which humans and nature can exist in productive harmony, that permit fulfilling the social, economic, and other requirements of present and future generations of Americans” (Bush 2007).

Two years later, President Obama issued Executive Order 13514, “Federal Leadership in Environmental, Energy, and Economic Performance,” which directs each federal agency to appoint a sustainability coordinator to oversee efforts to reduce greenhouse gases and enhance energy efficiency (Obama 2009).

Managing federal facilities is a narrower and easier task than creating sustainability polices that multiple agencies would implement within the constraints of federal statutes. Policy makers are only now recognizing that sustainability is an integrating concept that calls for coordination of policies affecting land, water, and air policies. For example, federal policies on procurement already reflect sustainability goals by defining requirements for greener and energy efficient products (GSA 2011).

Because the issue of sustainability applies throughout the federal government, there is a need for coordination and mutual support among federal agencies. For example, EPA's work in the area of water resources is heavily dependent upon activities of the US Geological Survey and state agencies. Today federal agencies are reassessing their roles in advancing sustainability. Although many federal agency reports consider a range of sustainability issues, there is no government-wide management strategy focusing on key national issues related to sustainability. A new National Research Council committee is currently undertaking a study examining "sustainability linkages in the federal government” (National Research Council 2011b), which will begin to address these issues.

Sustainability at the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency

Sustainability is very closely connected to environmental protection and to the mission of the US EPA. In the 40 years since EPA was created, the Agency has adapted to changing environmental issues and has been moving toward adopting sustainability as a key element of environmental policy (Grossarth and Hecht 2007, Fiksel et.al 2009, Hecht 2011).

At the beginning of the 1970s, environmental protection was largely focused on the most harmful industrial emissions and threats to occupational health and safety. When EPA was created (see Origins of the Environmental Protection Agency), environmental challenges were highly visible and easy for the public to understand. In a 1995 retrospective explaining the view of environmentalism, EPA’s first Administrator, William Ruckelshaus, described the early environmental movement as necessary because “[t]he protective functions of government were grossly inadequate, industry had no interest in stopping pollution and, absent government control, would not protect the public interest” (Ruckelshaus 1995).

Science writer Philip Shabecoff described EPA’s early evolution in these terms:

Agency became the federal government’s watchdog, police officer and chief weapon against all forms of pollution. [It] was thus created without the benefit of any statute enacted by Congress. It quickly became the lightning rod for both the nation’s hopes of cleaning up pollution and its fears about intrusive federal regulations (Shabecoff 1993).

Expanding into a new area, EPA completed its first risk assessment report in 1975; a 1976 report underscored the link between risk assessment and development of regulations. The preamble of the latter report stated that rigorous assessments of health risk and economic impact would be undertaken as part of the regulatory process (U.S. EPA 1976).

The risk paradigm was further advanced when in 1983 the National Research Council’s Committee on the Institutional Means for Assessment of Risks prepared a landmark report, commonly known as the “Red Book” (NRC 1983).

Today EPA is expanding its role from enforcer and risk assessor to become also a problem solver, drawing on science and innovation to advance sustainable management practices. The concepts of sustainability science and innovation are being more aggressively pursued.

Advancing the ideas of sustainability and sustainability science, the Administrator commissioned the National Research Council (NRC) to consider how to incorporate the theme of sustainability into all of EPA’s activities. This report, dubbed the “Green Book,” strongly urged EPA to adopt a sustainability framework and to advance methods and approaches that would help EPA and all decision makers make better and more informed environmental decisions (NRC 2011a).

In a practical way, the starting point for achieving sustainability is asking the right questions. Why aim merely to reduce toxic waste when we can eliminate it with new chemicals and processes? Why handle and dispose of growing amounts of waste when we can recover and utilize wastes as valuable resources? These questions are relevant to both business and government.

While EPA is largely viewed as a regulatory agency, it has many other roles to play that can advance sustainable management practices, meet its core mandates, and help shape the global marketplace.

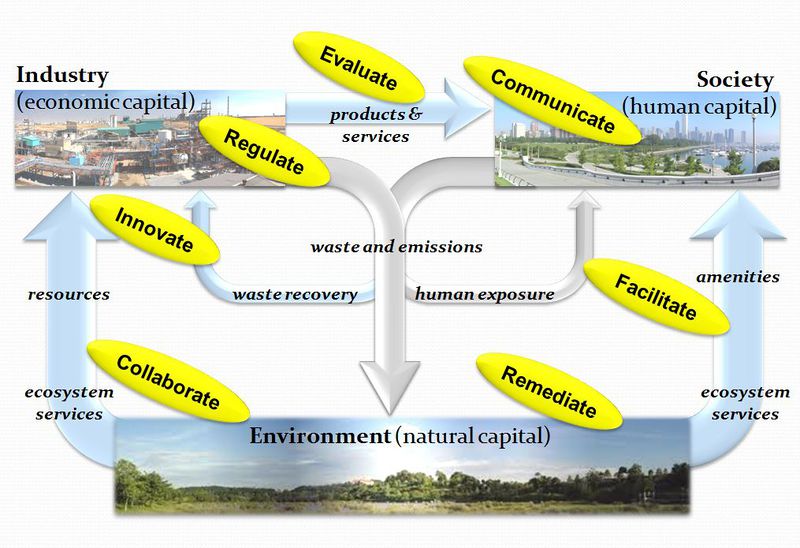

In the Green Book, the NRC noted the many roles that EPA plays including a convener of stakeholders, a thought leader, a science and technology innovator, an educator, and a regulator. Figure 2 summarizes seven principal roles that EPA can play to influence the sustainable development of industrial, societal, and environmental systems (Fiksel et al. 2012).

- Regulate industry practices and technologies in order to assure the sustainable utilization and stewardship of energy, materials, and natural resources.

- Evaluate the sustainability of products and services that are marketed to society and provide such incentives as public recognition or purchasing preference.

- Communicate to stakeholders and the general public regarding the importance of sustainability and the urgency of adopting safe and sustainable practices.

- Facilitate behaviour change through economic incentives and technical assistance programs aimed at protecting human health and environmental sustainability.

- Remediate natural resources that have been degraded by restoring ecosystem integrity and establishing sustainable land use practices.

- Collaborate with industry and other groups to protect natural capital and assure the continued availability of critical ecosystem goods and services.

- Innovate using scientific tools, methods and approaches to design sustainable solutions that improve the resource efficiency and safety of industrial activities.

Figure 2. Systems View of Sustainability Policy Options

Figure 2. Systems View of Sustainability Policy Options

Summary

The current approach to resource management is not sustainable, and the unintended consequences of many past choices have left a legacy of challenging environmental problems. Moving from the status quo towards sustainability requires new approaches to problem solving that take entire systems into account, rather than isolated components. In our increasingly inter-connected world, environmental, social, and economic factors must be considered simultaneously, including cumulative effects that occur over long time scales.

A number of synergistic forces have been described in this article. Government polices are promoting sustainable management practices. Advances in science and technology and innovation are essential to promote sustainable solutions. Much of the business community in the United States now sees sustainability as a means to reduce long-term risk, enhance competitiveness, and reduce costs. Public understanding and support of sustainability is growing. Only with effective coordination of these four elements—effective laws, policies, and regulations; advances in science and technology; green business strategies; and public support and participation—can we achieve genuine progress in sustainability.

References

- Anastas, P. and J. Warner. 1998. Green Chemistry: Theory and Practice. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Bush, G. 2007.Executive Order 13423, Strengthening Federal Environmental, Energy, and Transportation Management. Accessed 18 September

- Council on Environmental Quality and Department of State. 1980. Global 2000 Report to the President, Washington, Council for Economic Quality.

- Council on Environmental Quality and Department of State. 1981. Global Future: Time to Act. Washington, Council for Economic Quality. Accessed 12 September 2011

- Daily Beast. 2011. The World’s Greenest Companies. Accessed 26 October 2011 at http://www.thedailybeast.com/topics/green-rankings.html

- Dow Jones Sustainability Indexes. 2011. Corporate Sustainability. Accessed 13 September 2011.

- Fiksel J. 2006. Sustainability and Resilience: Towards a Systems Approach. Sustainability Science, Practice, and Policy 2(2) 1–8.

- Fiksel J., T. Graedel, A. Hecht, D. Rejeski, G.S. Sayler, P.S. Senge, D.M. Swackhamer, and T.L. Theis. 2009. U.S. EPA at 40: Bringing Environmental Protection into the 21st Century. Environmental Science & Technology 43:8716–8720.

- Fiksel, J. 2009. Design for Environment: A Guide to Sustainable Product Development. New York, McGraw-Hill.

- Fiksel J., R. Bruins, A. Gilliland, A. Gatchett, and M. ten Brink. (Forthcoming 2012.) The Triple Value Model: A Systems Approach for Sustainable Solutions. Clean Technology and Environmental Policy.

- General Services Administration. 2011. Strategically Sustainable. (Forthcoming.) Accessed 18 September 2011.

- Global Footprint Network. 2010. Ecological Footprint. Accessed 18 September 2011

- Grossarth, S.K. and A. Hecht. 2007. Sustainability at the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 1970–2020. Ecological Engineering 30:1–8.

- Hecht A. 2009. The Next Level of Environmental Protection: Business Strategies and Government Policies Converging on Sustainability. Sustainable Development Law & Policy 7 (Fall) 19–25.

- Hecht, A. (In press, 2011.) It’s OK to Talk about Sustainability. In: Sustainability Science: The Emerging Paradigm and the Urban Environment. M.F. Weinstein and R.E. Turner (eds.). New York, Springer.

- Holdren, J. 2008. Science and Technology for Sustainable Well-being. Science 319: 424-434.

- House Committee on Science. 1998. Unlocking Our Future: Toward a New National Science Policy. Washington.

- Jackson, L. 2010.Remarks at the National Press Club, As Prepared. Accessed 13 September 2010

- Kates, R.W. and T.M. Parris. 2005. Long-term Trends and a Sustainability Transition. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 100(14): 8062–8067.

- Millennium Development Goals. Accessed 25 October 2011 at http://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/

- Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. 2005. Millennial Ecosystem Assessment. Washington: Island Press. Accessed 13 September 2011.

- National Research Council (NRC). Committee on the Institutional Means for Assessment of Risks. 1983.Risk Assessment in the Federal Government: Managing the Process (“Red Book”). Washington, National Academy Press. Accessed 12 September 2011.

- National Research Council (NRC). 2011a. Sustainability and the U.S. EPA. Accessed 18 September 2011.

- National Research Council (NRC). 2011b. Sustainability Linkages in the Federal Government. Accessed 18 September 2011.

- Nidumolu, R.A., C.K. Prahalad, and M.R. Rangaswami. 2009. Why Sustainability Is Now the Key Driver of Innovation. Harvard Bus Rev 87(9)56–64.

- Obama, B. 2009. Executive Order 13514, “Federal Leadership in Environmental, Energy, and Economic Performance.” Accessed 19 September 20011.

- Pike Research. 2011.Green Chemistry. Accessed 13 September 2011.

- Pinchot, G. 1910. The Fight for Conservation. New York, Doubleday, Page & Company.

- Stafford, S.G. et al. 2009. Now is the Time for Action: Transitions and Tipping Points in Complex Environmental Systems. Washington: National Academies Press.

- Sullivan N. and R. Schiafo. 2005. Talking Green, Acting Dirty. NY Times June 12.

- UNEP Finance Initiative. 2011. Accessed 27 October 201.

- United Nations. 1992. Earth Summit. Accessed 13 September 2011.

- United Nations Population Division. 2011. World Population Prospects: The 2010 Revision. New York: United Nations. Accessed 17 September 2011.

- U.S. Congress. 1970. The National Environmental Policy Act of 1970. Accessed 13 September 2011.

- U.S. EPA. 1976. Interim Procedures and Guidelines for Health Risk and Economic Impact Assessments of Suspected Carcinogens. Washington: U.S. EPA.

- U.S. EPA. 2009. Sustainable Materials Management: The Road Ahead. (U.S. EPA 530R09009). Washington: U.S. EPA.

- World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD). 2010. Vision 2020. Accessed 13 September

- World Commission on the Environment and Development. 1987. Our Common Future. New York: Oxford University Press. Accessed 13 September 2011.