Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary

Contents

Introduction

Stellwagen Bank is the centerpiece of the Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary (Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary) , which encompasses a total of 638 square nautical miles, or 842 square miles. The sanctuary also includes all of Tillies Bank (situated to the northeast of Stellwagen Bank) and southern portions of Jeffreys Ledge (situated to the north). The western boundary line of the sanctuary is approximately 25 miles east of Boston, Massachusetts; the southern boundary is three miles from Provincetown, MA while the northwestern boundary is three miles from Gloucester, MA. From the sanctuary's Scituate-based headquarters, the distance is approximately 11 miles.

Stellwagen Bank is a shallow, primarily sandy feature, curving in a southeast to northwest direction for 19 miles. It is roughly 6 miles across at its widest point at the southern end. Water depths over and around the bank range from 65 feet on the southwest corner to depths of about 600 feet in deep passages to the northeast. Massachusetts Basin on the western side of the sanctuary levels off at about 300 feet in depth, while the top of the bank averages about 100 to 120 feet.

The sanctuary boundary occurs entirely within federal waters (beyond the three-mile limit of commonwealth of Massachusetts jurisdiction). The southern border follows a line tangential to the seaward limit of commonwealth jurisdiction adjacent to the commonwealth-designated Cape Cod Bay Ocean Sanctuary; and is also tangential to waters designated by the commonwealth as the Cape Cod Ocean Sanctuary. The northwest border of the sanctuary coincides with the commonwealth-designated North Shore Ocean Sanctuary.

History

Discovery

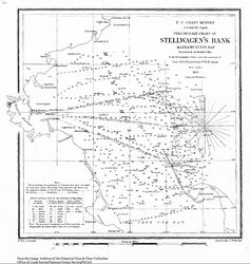

Before discovery of Stellwagen Bank, there had been some knowledge of the area. Fishermen had called it Middle Ground for years. Some charts had noted shallows in the area. But it took Henry Stellwagen, a Lieutenant Commander of the U.S. Navy on loan to the U.S. Coast Survey (the forerunner to NOAA's Coast and Geodetic Survey) working from the US Coast Survey Steamer BIBB, to actually map the full length and breadth of the bank in 1854 and 1855.

He wrote on October 22, 1854: "I consider I have made an important discovery in the location of a 15 fathom bank lying in a line between Cape Cod and Cape Ann—with 40 and 50 fathoms inside and to northward of it and 35 fathoms just outside it. It is not on any chart I have been able to procure. We have traced nearly five miles in width and over six miles in length, it no doubt extending much further."

The importance of this discovery was not lost on Alexander Bache, the superintendent of the Coast Survey, who noted in the 1854 annual report that: "The hydrographer in Massachusetts Bay had been rewarded for his labors by the discovery in the entrance of an extensive bank, of which he had given the position and defined the limits, with from ten and a half to fourteen and a half fathoms on it, lying across the entrance, and serving thus as an excellent mark for navigators entering this important bay. I propose to call this, from the name if its discoverer, Stellwagen's Bank."

According to Stellwagen, "I consider promulgation of this discovery as very essential to navigators, and that the knowledge of it will highly benefit commanders of vessels bound in during thick weather, by day or night. By it they can not only ascertain their distance to the eastward of the coast, but, by attention to the lead after passing inside, a good idea of latitude may also be obtained."

This military man with a talent for hydrography was also an inventor—he developed a sounding device with a steel cup covered by leather valves that could bring up specimens of the sea bottom. Used for many years by the Coast Survey, the invention won for him the Scott Premium Medal from the Franklin Institute.

With his sounding device, Stellwagen not only measured the size of the bank, but the type of sediment on and around it. Said he, "The northern end of the bank has rocky bottom, with, however, a slight covering of fine black sand. The middle and southern parts are coarse white and yellow sand. The bottom inside of the bank, in deep water is generally a green unctuous mud, or ooze."

Historical Use

The Stellwagen Bank area has seen active vessel traffic for hundreds of years, with the plethora of ships passing through these waters illustrating the history of New England. The evolution in the size, design and capacity of fishing boats, cargo vessels and passenger ships has paralleled the economic development and population growth of the region.

The Pilgrims came to the Plymoth Colony seeking religious freedom, but also the economic potential of bountiful fish stocks in the local waters. Stellwagen Bank and offshore banks, including Georges and Grand, drew fishing vessels from the ports of Boston, Salem, Beverly, Marblehead and Gloucester. Today, commercial fishing vessels from Maine to New Jersey regularly visit these waters, while legions of recreational fishermen also try their hand at cod, tuna and other species.

Whaling, once an industry on Cape Cod, has been exchanged for whale watching. Truro and Provincetown were whaling towns in the 17th and 18th centuries – first with shore-based harvesting of stranded animals and then later hunting from boats. By 1760, some 12 whaling ships called Provincetown their home. Now, whale watching companies depart from Provincetown, and a dozen or so other companies from Plymouth to Newburyport.

Passenger vessels have carried the wealthy and privileged as well as the “huddled masses yearning to breathe free.” Immigration in the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries brought families from England, Ireland, and many other European countries to these shores. Cargo vessels have been bringing goods from around the world to Boston. Travel between the colonies, and later the states, was possible via vessels that ranged up and down the coast, with a passage over Stellwagen Bank a necessity for any Boston-bound ship.

Today, the sanctuary is studying the amount and type of vessel traffic that passes through the sanctuary, and how that traffic might be better managed to protect marine mammals in sanctuary waters. The Vessel Use Survey, undertaken by the Sanctuary in 1994-95 and 2001-02, shows patterns in human use of the sanctuary during the past decade.

Maritime History

The maritime history of the Stellwagen Bank National Marine encompasses much of New England's history. As the Ice Age glaciers began retreating from eastern Massachusetts around 16,000 year ago, portions of Stellwagen Bank and Jeffreys Ledge were dry and home to grasses, forests, and Pleistocene animals. It is likely that between 11,000 and 12,000 years ago, Paleoindians inhabited these areas and exploited the rich marine resources found along the shore. Rising sea levels slowly inundated Massachusett's Bay, pushing the native populations to settlements along the current shoreline. For thousands of years Native Americans utilized the vast fish and shellfish resources of Massachusetts Bay developing rich cultures.

During the thousands of years of human occupation of the Massachusetts' coastline, waterborne transportation was an essential part of the region's communication network. Vessels of many shapes and sizes have carried a variety of cargos and multitudes of persons to and from Massachusetts ports. Beginning with the native cultures and continued by the earliest colonists who cut settlements from the thick forests and fished along the shore, New Englanders have derived tremendous economic benefit from their close association with the sea. New Englanders have traveled the breadth of the globe in sailing ships, trading with far flung cultures or harvesting the bounty of the sea. At the beginning and end of each voyage, many of these intrepid mariners crossed through the waters that are now recognized as the Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary.

Designation History

The designation of Stellwagen Bank as the nation's twelfth (and New England's first) National Marine Sanctuary was the culmination of over a decade of effort. Stellwagen Bank was first nominated for consideration as a national marine sanctuary in 1982 by the Center for Coastal Studies in Provincetown, Massachusetts and the Defenders of Wildlife in Washington, D.C. The following year the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) added Stellwagen Bank to its "Site Evaluation List" from which NOAA chooses ocean areas as active candidates for designation as national marine sanctuaries.

NOAA elevated the Stellwagen Bank proposal to Active Candidate status on April 19, 1989 (54 FR 15787). This was done in response to a requirement in the 1988 amendments to the National Marine Sanctuary Program that a prospectus on the Stellwagen Bank proposal be submitted to Congress by September 30, 1990 (P.L. 100-627, s. 205(b)(1)). NOAA commenced gathering public comment and prepared the Draft Environmental Impact Statement/Management Plan and the Prospectus to Congress. These were published on February 8, 1991, initiating a 60-day public comment period and a 45-day Congressional review period. During the comment period, a series of public hearings was held, 860 written comments were submitted, and petitions signed by more than 20,000 persons supporting designation of the Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary were received by NOAA (Sanctuaries and Reserves Division, 1993).

Marine Life

The Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary was designated for a multitude of reasons, not the least of which was its long history of human use and its high natural productivity.

Two distinct peak productivity periods produce a complex system of midwater and benthic habitats. These communities support benthic and pelagic species by providing cover and anchoring locations for invertebrates; they also provide feeding and nursery grounds for more than a dozen cetacean species including the endangered humpback, northern right, sei, and fin whales. The area supports foraging activity by diverse seabird species, dominated by loons, fulmars, shearwaters, storm petrels, cormorants, phalaropes, alcids, gulls, jaegers, and terns. Fish and invertebrate populations subject to seasonal and migration shifts include both demersal and pelagic species, such as bluefin tuna, herring, cod, flounders, lobster, and scallops. Leatherback and Kemp's ridley sea turtles (endangered species) use the area for feeding.

Data strongly suggest the presence of over 50 shipwreck sites within the sanctuary. Important sites that have already been investigated include the historically significant wreck of the steamship Portland which sank in 1898 during a gale named after the ship. Large vessel traffic is steady due to the fact that the major shipping lanes to Boston pass through the Sanctuary, The presence of whales and fish, in turn, attract vessels engaged in watching the former and catching the latter.

Further Reading

| Disclaimer: This article is taken wholly from, or contains information that was originally published by, the National Marine Sanctuary. Topic editors and authors for the Encyclopedia of Earth may have edited its content or added new information. The use of information from the National Marine Sanctuary should not be construed as support for or endorsement by that organization for any new information added by EoE personnel, or for any editing of the original content. |